Introduction

Prenatal depression, affecting a significant 10% to 20% of pregnancies in developed nations, is an increasing concern with substantial implications for both maternal and child health. Notably, it’s linked to depression in adolescent offspring, even after accounting for maternal depression throughout the child’s life. The decision to treat prenatal depression with medication is complex, often overshadowed by fears of adverse effects on the fetus and a lack of definitive clinical guidelines. Many pregnant women discontinue or hesitate to start antidepressants during pregnancy, highlighting the urgent need for more research to guide clinical decisions and ensure informed patient care.

Concerns about antidepressant exposure during pregnancy arise from the fact that these medications can cross the placenta and blood-brain barrier. Serotonin, influenced by antidepressants, plays a critical role in fetal neurodevelopment. Disruption of the serotonergic system can have long-term consequences, potentially increasing vulnerability to mood disorders later in life. However, it’s also crucial to consider confounding factors, such as the severity and nature of the depression itself, which may independently contribute to these associations. Distinguishing between the impact of prenatal depression and prenatal antidepressant exposure is vital for effective prevention and treatment strategies.

While childhood depression becomes more prevalent with age, particularly in adolescents aged 12 and older, research on the long-term effects of in utero antidepressant exposure on adolescent depression remains limited. Existing studies have shown potential links between maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy and increased risk of depression diagnoses in teenagers. However, these studies often lack crucial details, such as restricting antidepressant use to mothers diagnosed with depression and accounting for pre-existing versus new-onset depression during pregnancy. Furthermore, the impact of prenatal antidepressant use on adolescent suicidality is largely unexplored, a significant gap given the alarming rates of suicidal thoughts and attempts among adolescents.

This study addresses these critical gaps by examining the association between maternal prenatal antidepressant use—specifically in mothers diagnosed with depression, including 296.30 Diagnosis and related codes as defined by ICD-9—and adolescent depressive symptoms and suicidality. Using a large, diverse sample representative of Northern California, this research aims to clarify whether prenatal depression itself, or the use of antidepressants to treat it, is more strongly associated with adverse mental health outcomes in adolescence. The findings have the potential to significantly inform clinical practice and support shared decision-making regarding antidepressant use during pregnancy.

Methods

Setting and Participants

The data for this prospective cohort study were derived from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) electronic health record (EHR) system and research databases. KPNC is an integrated healthcare system serving a diverse population in Northern California. The study population was drawn from a birth cohort of infants born at KPNC facilities between 2003 and 2011. Adolescents in this cohort, upon attending well-teen primary care appointments, were asked to complete a questionnaire including mental health assessments like the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) and questions about suicidality.

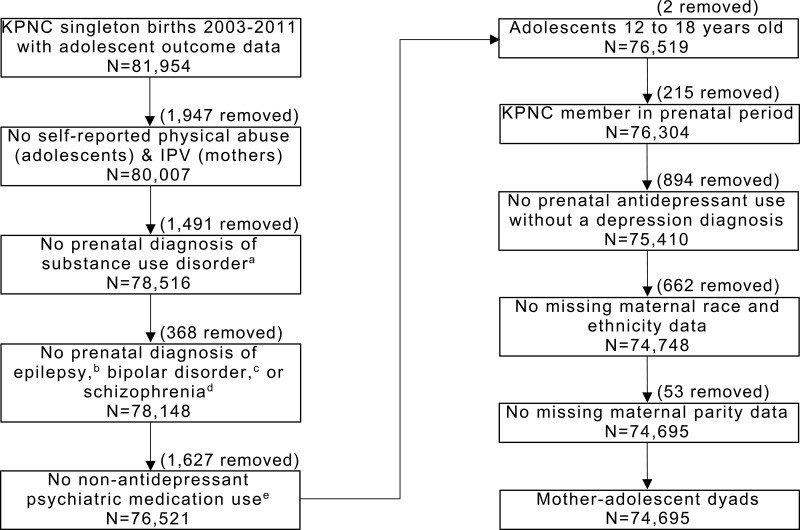

From an initial pool of 81,954 births with adolescent PHQ-2 data, several exclusions were made to minimize confounding variables. These included excluding mother-adolescent dyads where mothers had reported intimate partner violence, substance use disorder, epilepsy, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia during pregnancy. The diagnoses were identified using specific ICD-9 codes, including 296.30 and related codes for depression diagnoses (296.20-296.25, 296.30-296.35, 300.4, 311), as detailed in Figure 1 of the original article. Dyads were also excluded if mothers used non-antidepressant psychiatric medications during pregnancy, if adolescents reported physical abuse, or if adolescents were under 12 years old at the time of PHQ-2 completion. Further exclusions were applied to ensure mothers were KPNC members during pregnancy and to remove dyads where mothers used antidepressants without a depression diagnosis, as this group was considered clinically heterogeneous. Finally, dyads with missing covariate data were excluded, resulting in an analytic sample of 74,695 mother-adolescent dyads. The study received approval from the KPNC Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1: Inclusion criteria for the study, outlining the process of participant selection and exclusions based on various factors, including maternal diagnoses and medication use during the prenatal period.

Measures

Exposure Variables

The primary exposure variables were maternal depression diagnosis and antidepressant use during the prenatal period. The prenatal period was defined as starting 30 days before pregnancy and continuing until delivery. Depression diagnosis was determined using ICD-9 codes, encompassing 296.30 diagnosis for Major Depressive Disorder, single episode, unspecified, along with other related codes (296.20-296.25, 296.30-296.35, 300.4, 311).

Prenatal antidepressant use was defined as purchasing one or more antidepressant prescriptions from a KPNC outpatient pharmacy during the prenatal period. The study considered total exposure across the prenatal period, acknowledging prior research suggesting that the duration of gestational exposure, rather than timing or dosage, is more relevant to offspring outcomes. Antidepressants included SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, atypical antidepressants, and serotonin modulators.

Exposure groups were categorized into three:

- Medication Use (Med): Prenatal depression diagnosis and prenatal antidepressant use.

- No Medication Use (No-Med): Prenatal depression diagnosis and no prenatal antidepressant use.

- Neither Depression Nor Medication (NDNM): Neither prenatal depression diagnosis nor prenatal antidepressant use.

Outcome Variables

The outcome variables were adolescent depressive symptoms and suicidality, self-reported on their most recent well-teen health questionnaire. Depressive symptoms were measured using the PHQ-2, a two-question screening tool assessing the frequency of depressed mood and anhedonia over the past two weeks. Scores range from 0 to 6, with a score of ≥3 indicating depressive symptoms. Suicidality was assessed by asking adolescents if they had seriously considered suicide, made a plan, or attempted suicide in the past two weeks, with “Yes” or “No” response options.

Covariates

Several maternal factors were considered as covariates: maternal age at delivery, anxiety diagnosis during pregnancy, depression diagnosis in the year before pregnancy (pregravid depression), maternal race and ethnicity, parity, and Medicaid insurance status during pregnancy. Maternal age was categorized into groups, and race and ethnicity were categorized into Hispanic; NH Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander; NH Black; NH Indigenous; NH Multiracial; and NH White. Adolescent characteristics, including gestational age and sex assigned at birth, were also considered.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests were used for descriptive analyses. Multivariable logistic regression models were employed to analyze associations between maternal prenatal depression, antidepressant use, and adolescent depressive symptoms and suicidality. Mixed effects logistic regression models, clustering adolescents at the mother level, were used to account for non-independence between siblings. NDNM was used as the reference group to examine intergenerational depression risk, and No-Med was the reference group to assess the impact of prenatal antidepressant use among mothers with depression. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to redefine antidepressant exposure as two or more purchases, and as SSRI monotherapy.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 details the demographic characteristics of the 74,695 mother-adolescent dyads, stratified by prenatal exposure group (Med, No-Med, NDNM). Mothers with prenatal depression were more likely to have multiple children and Medicaid insurance. Within the prenatal depression groups, mothers who used antidepressants (Med) were more likely to be older and NH White compared to those who did not (No-Med).

Table 1. Selected Characteristics by Exposure to Maternal Depression and Antidepressant Use During the Prenatal Period, N (%)

| Characteristic | Med (N=1290) | No-Med (N=1721) | NDNM (N=71,684) | Total (N=74,695) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age at delivery (years) | ||||

| ≤19 | 2.40 | 5.00 | 3.27 | 3.30 |

| 20–24 | 10.23 | 14.58 | 13.58 | 13.55 |

| 25–29 | 23.49 | 27.43 | 27.96 | 27.87 |

| 30–34 | 31.24 | 28.07 | 32.46 | 32.34 |

| 35–39 | 24.73 | 19.58 | 18.28 | 18.42 |

| ≥40 | 7.91 | 5.35 | 4.45 | 4.53 |

| Prenatal Medicaid insurance (Yes) | 4.81 | 5.35 | 2.89 | 2.98 |

| Parity (live births) | ||||

| 0 | 38.84 | 39.63 | 43.34 | 43.17 |

| 1 | 33.88 | 33.59 | 35.09 | 35.03 |

| ≥2 | 27.29 | 26.79 | 21.57 | 21.79 |

| Maternal race and ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 22.33 | 32.71 | 28.84 | 28.82 |

| NH Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander | 6.36 | 12.90 | 25.95 | 25.31 |

| NH Black | 5.89 | 11.39 | 7.07 | 7.15 |

| NH Indigenous | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

| NH Multiracial | 5.27 | 4.24 | 3.60 | 3.65 |

| NH White | 59.69 | 38.06 | 34.11 | 34.64 |

| Maternal prenatal anxiety diagnosis (Yes) | 31.86 | 24.93 | 3.08 | 4.08 |

| Maternal pregravid depression diagnosis (Yes) | 51.24 | 28.47 | 2.77 | 4.20 |

Table 2 shows characteristics stratified by adolescent depressive symptoms and suicidality. Approximately 9% of adolescents reported depressive symptoms and 2% endorsed suicidality. Adolescents with these outcomes were more likely to be female and born to mothers with pregravid depression.

Table 2. Selected Characteristics by Depressive Symptoms and Suicidality in Adolescents, N (%)

| Characteristic | Depressive Symptoms (Yes, N=6384) | Depressive Symptoms (No, N=68,311) | Suicidality (Yes, N=1314) | Suicidality (No, N=72,331) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age at delivery (years) | ||||

| ≤19 | 4.32 | 3.20 | 4.49 | 3.28 |

| 20–24 | 15.04 | 13.41 | 14.92 | 13.52 |

| 25–29 | 25.41 | 28.10 | 26.10 | 27.90 |

| 30–34 | 30.26 | 32.53 | 29.68 | 32.39 |

| 35–39 | 19.77 | 18.30 | 19.71 | 18.39 |

| ≥40 | 5.20 | 4.46 | 5.10 | 4.51 |

| Prenatal Medicaid insurance (Yes) | 4.31 | 2.86 | 5.78 | 2.93 |

| Parity (live births) | ||||

| 0 | 42.78 | 43.21 | 42.24 | 43.18 |

| 1 | 33.58 | 35.17 | 31.81 | 35.11 |

| ≥2 | 23.64 | 21.62 | 25.95 | 21.71 |

| Maternal race and ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 33.43 | 28.39 | 28.84 | 28.79 |

| NH Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander | 20.19 | 25.79 | 21.77 | 25.42 |

| NH Black | 8.63 | 7.01 | 10.50 | 7.07 |

| NH Indigenous | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.43 |

| NH Multiracial | 3.60 | 3.65 | 3.42 | 3.64 |

| NH White | 33.60 | 34.74 | 34.93 | 34.65 |

| Maternal pregravid depression diagnosis (Yes) | 6.03 | 4.03 | 5.94 | 4.18 |

| Sex assigned at birth of adolescent (Female) | 67.43 | 47.36 | 76.18 | 48.55 |

Primary Analyses

Prenatal Depression and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents

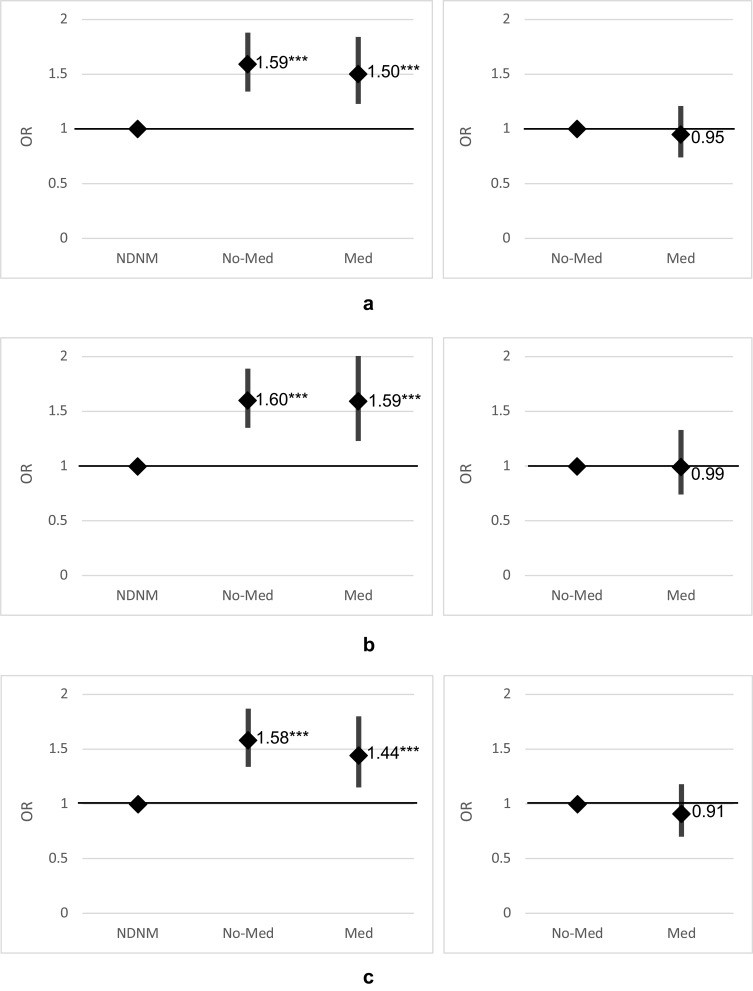

After adjusting for covariates, maternal prenatal depression was significantly associated with higher odds of adolescent depressive symptoms compared to NDNM. The odds ratios were similar for both the Med group (OR: 1.50, CI: 1.23–1.84) and the No-Med group (OR: 1.59, CI: 1.34–1.88).

Prenatal Antidepressant Use and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents

Among adolescents whose mothers had prenatal depression, there was no significant difference in depressive symptoms between those exposed to antidepressants in utero (Med) and those unexposed (No-Med) (OR: 0.95, CI: 0.74–1.21).

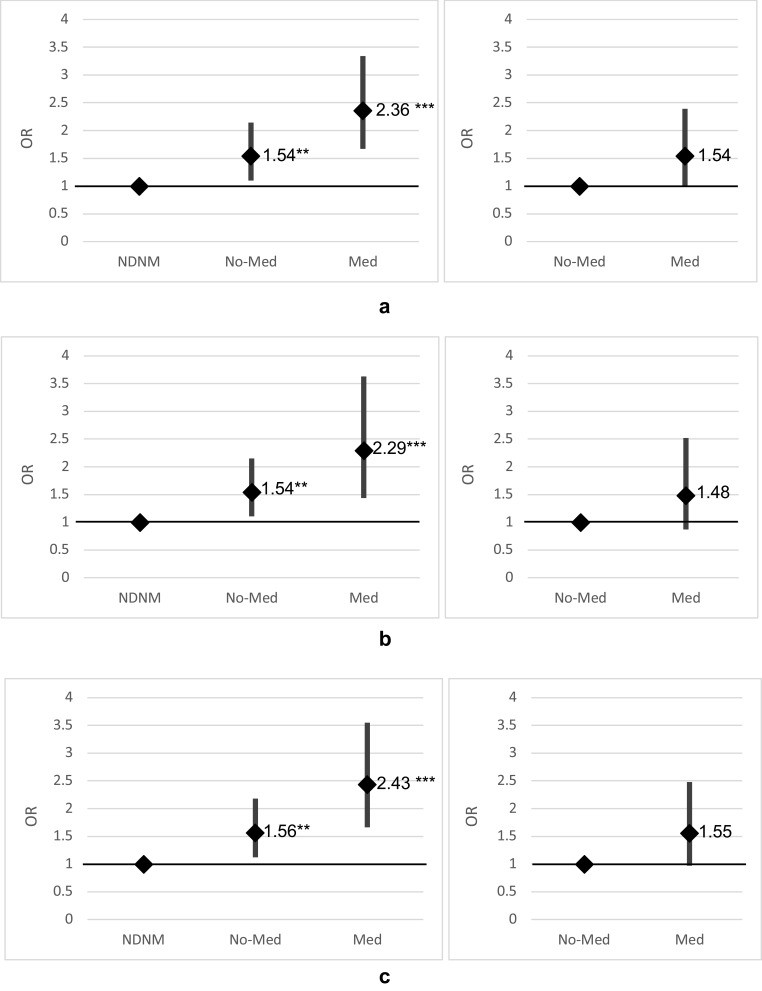

Prenatal Depression and Suicidality in Adolescents

Both prenatal depression exposure groups (Med and No-Med) showed higher odds of adolescent suicidality compared to NDNM. The Med group had a higher odds ratio (OR: 2.36, CI: 1.67–3.34) than the No-Med group (OR: 1.54, CI: 1.10–2.14).

Prenatal Antidepressant Use and Suicidality in Adolescents

While not statistically significant, there was a marginal association between prenatal antidepressant exposure and increased odds of suicidality among adolescents with prenatal depression (Med vs. No-Med OR: 1.54, CI: 0.99–2.39).

Figure 2: Adjusted odds ratios for the association between maternal prenatal depression and antidepressant use with depressive symptoms in adolescent children, across different sensitivity analyses.

Figure 3: Adjusted odds ratios for the association between maternal prenatal depression and antidepressant use with suicidality in adolescent children, across different sensitivity analyses.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses, redefining antidepressant use as two or more purchases or as SSRI monotherapy, yielded results consistent with the primary analyses for both depressive symptoms and suicidality. Prenatal depression remained associated with increased risk, while prenatal antidepressant use did not significantly increase the risk of depressive symptoms, but showed a marginal, non-significant association with suicidality.

Discussion

This study’s findings highlight that maternal prenatal depression is associated with increased depressive symptoms and suicidality in adolescent children. Importantly, within the context of prenatal depression, in utero antidepressant exposure did not appear to elevate the risk of depressive symptoms in adolescents. While a marginal, statistically non-significant association with suicidality was observed in adolescents exposed to antidepressants, further research is warranted to fully understand this potential link.

These results align with previous research suggesting that maternal depressive symptoms, rather than prenatal antidepressant use alone, are more strongly linked to internalizing behaviors and affective disorders in young children. This study extends this understanding into adolescence, using a large, racially and ethnically diverse sample and carefully controlling for confounding factors, including restricting the analysis to mothers diagnosed with depression, including 296.30 diagnosis, and considering the chronicity of maternal depression.

The study’s strengths include its large sample size, diverse population, use of EHR data to minimize bias, and the novel examination of adolescent suicidality in relation to prenatal antidepressant exposure. By using primary care settings for adolescent mental health assessments, the study also mitigated potential detection bias present in studies relying on secondary or tertiary care settings.

Limitations include the inability to control for all potential confounders, such as alcohol or drug use during pregnancy (beyond excluding mothers with substance use disorders), the precise timing and duration of maternal depressive episodes, and the severity of prenatal depression. Medication adherence and treatment effectiveness were also not directly assessed.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the complex relationship between prenatal depression, antidepressant use, and adolescent mental health. The findings suggest that while prenatal depression poses a risk for adolescent depressive symptoms and suicidality, in utero exposure to antidepressants, when used to treat maternal depression, does not appear to exacerbate the risk of depressive symptoms and may have a marginal association with suicidality that requires further investigation.

Conclusion

This research contributes to the growing body of literature guiding clinical decisions regarding antidepressant use during pregnancy. It underscores the importance of addressing maternal prenatal depression to mitigate potential risks to adolescent mental health. While prenatal antidepressant use does not seem to independently increase the risk of adolescent depressive symptoms, the marginal association with suicidality warrants further exploration. Future research should focus on monitoring the severity of maternal prenatal depressive symptoms, treatment efficacy, and long-term outcomes for children exposed to both prenatal depression and antidepressants. These findings can inform shared clinical decision-making, helping healthcare providers and pregnant women make more informed choices about managing depression during pregnancy.