Introduction

Craniosynostosis, the premature fusion of cranial sutures, is a condition typically identified and addressed in infancy. Sagittal suture synostosis (SSS), specifically, involves the early closure of the sagittal suture, which runs along the top of the skull. While usually diagnosed within the first months of life, a delayed diagnosis of craniosynostosis, particularly sagittal synostosis, can lead to a range of complications affecting brain development, intracranial pressure (ICP), and neurocognitive functions. Furthermore, the altered head shape can impact self-perception and self-esteem, especially as children grow older and become more aware of their appearance.

This article delves into the complexities of Craniosynostosis Late Diagnosis, presenting a unique case of a 10-year-old boy who underwent successful treatment for non-syndromic sagittal synostosis. This case underscores the challenges in recognizing craniosynostosis in older children, the potential consequences of delayed intervention, and the positive outcomes achievable even when treatment is initiated later in life. While aesthetic concerns were primary for the patient and his family, the case also highlights associated neurobehavioral issues and vision problems, all of which improved significantly following total cranial vault remodeling.

Cranial sutures, the fibrous joints between the skull bones, are crucial for allowing skull deformation during birth and facilitating brain growth in early childhood. The sagittal suture, joining the parietal bones, is the last to fuse, typically remaining open until adulthood. Premature fusion of the sagittal suture results in sagittal synostosis, the most common form of craniosynostosis, accounting for over half of all cases. This condition leads to scaphocephaly, characterized by an elongated, narrow head shape and a reduced cephalic index. Typically, diagnosis occurs in infancy when parents or healthcare providers notice the unusual head shape or palpable bony ridges along the sagittal suture.

While approximately 20% of craniosynostosis cases are linked to genetic syndromes and involve multiple sutures, non-syndromic sagittal synostosis, like in our case, is more common. Factors such as mechanical deformation and fetal constraint have been implicated in its development, evidenced by higher prevalence in twins. Intrauterine compression and fetal positioning are proposed contributors. However, the exact cause remains unclear in many instances, emphasizing the need for heightened awareness and early detection even in the absence of apparent risk factors.

Limited research exists on craniosynostosis presenting after early childhood, making late diagnosis cases particularly valuable for understanding the long-term implications and treatment efficacy in older age groups. This case of a 10-year-old patient provides significant insights into the manifestations of untreated sagittal synostosis and the benefits of surgical correction even at a delayed stage. Beyond the aesthetic aspects, this case underscores the potential impact of prolonged skull volume restriction and delayed neurobehavioral development associated with craniosynostosis late diagnosis.

Case Presentation: A 10-Year-Old with Sagittal Synostosis Late Diagnosis

A 10-year-old boy presented to the Oxford Craniofacial Unit with a noticeably “egg-shaped” head, blurred vision, headaches, and dyspraxia. His medical history included attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), managed with methylphenidate and melatonin for 18 months prior to presentation. There was no family history of craniosynostosis or other craniofacial disorders, and his birth and early development were reported as normal.

Despite the mother noticing the unusual head shape from birth, referral to a craniofacial specialist only occurred when concerns about school bullying arose. This highlights a critical aspect of craniosynostosis late diagnosis – the initial signs might be subtle or overlooked, and aesthetic concerns can become the primary motivator for seeking medical attention later in childhood.

Examination and Diagnostic Confirmation

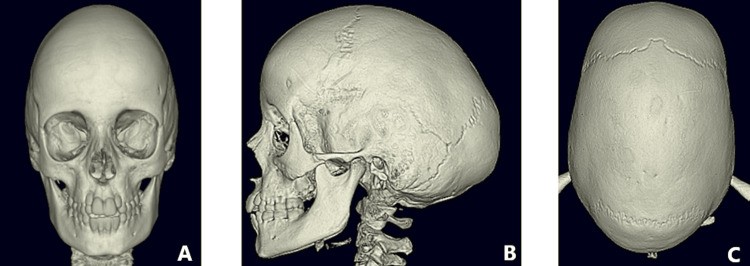

Physical examination revealed scaphocephaly, with a prominent forehead and occipital region, characteristic of sagittal synostosis. Genetic screening was negative for known craniosynostosis-related mutations, indicating a non-syndromic case. A CT scan with 3D reconstruction, the gold standard for diagnosing sagittal synostosis, confirmed the premature fusion of the sagittal suture.

Figure 1: Pre-operative CT scans illustrating sagittal synostosis. (A) Anterior-posterior view, (B) Lateral view, (C) Vertex view.

Interestingly, while imaging showed signs suggestive of raised ICP, such as copper beating and optic disc pallor, the measured ICP was within the normal range (7mmHg). This discrepancy emphasizes that normal ICP measurements do not always rule out the potential impact of craniosynostosis, particularly in cases of craniosynostosis late diagnosis.

Surgical Intervention: Total Cranial Vault Remodeling

The patient underwent total cranial vault remodeling using the lateral switch rotation technique. This surgical approach is designed to address the fused suture, correct cranial abnormalities, and provide stable, long-term results. The surgery was successful, and the patient experienced an uncomplicated recovery, being discharged from the hospital after five days.

Outcome and Follow-Up: Significant Improvements Post-Surgery

The primary goals of surgery – correcting the cranial deformity and preventing further progression – were successfully achieved. Remarkably, the patient reported immediate improvement in vision and resolution of a persistent “buzzing” sensation in his head upon waking up from surgery.

Figure 2: Anterior view comparison. (A) Pre-operative image, showcasing scaphocephaly. (B) Post-operative image, demonstrating corrected skull shape after cranial vault remodeling.

In the months following surgery, the patient’s vision continued to improve, reducing his dependence on glasses. His dyspraxia also showed notable improvement, and his ADHD medication dosage was initially reduced. Importantly, school reports indicated significant improvements in behavior and concentration.

The psychosocial benefits were equally profound. The patient described the surgery as “life-changing,” citing increased confidence and improved mental well-being. Long-term follow-up at the craniofacial clinic for seven years confirmed sustained positive outcomes, leading to his discharge from the service with patient and clinical team satisfaction.

Figure 3: Lateral view comparison. (A) Pre-operative image, showing elongated skull shape. (B) Post-operative image, displaying a more rounded and typical skull contour.

Discussion: Implications of Craniosynostosis Late Diagnosis

This case of craniosynostosis late diagnosis in a 10-year-old boy offers valuable insights into diagnostic challenges, delayed presentation consequences, and the efficacy of treatment even at an older age.

Diagnostic Difficulties and the Need for Increased Awareness

The delayed diagnosis in this case underscores the potential for missed or subtle signs of sagittal synostosis, particularly when presentation occurs later in childhood. It suggests a need for enhanced education for healthcare professionals, including health visitors and primary care practitioners, to improve early detection of craniosynostosis and scaphocephaly, even in the absence of typical early indicators. This is especially relevant in non-syndromic cases where genetic or environmental factors are not readily apparent. The patient’s male sex, a known risk factor for sagittal synostosis, was the only identifiable predisposing factor in this instance.

While genetic factors are increasingly recognized in craniosynostosis, particularly coronal and multi-suture synostosis, the etiology of non-syndromic sagittal synostosis remains complex and likely multifactorial. This case, lacking a clear genetic or mechanical cause, reinforces the idea that a combination of polygenic, epigenetic, and environmental factors may contribute to sagittal synostosis, highlighting the importance of considering it in differential diagnoses for scaphocephaly regardless of apparent cause.

Consequences of Delayed Presentation: Neurobehavioral and Visual Impacts

This case of craniosynostosis late diagnosis emphasizes that while sagittal synostosis is often considered an aesthetic concern, it can have significant functional implications, particularly when diagnosis is delayed. The patient’s long-standing headaches, tinnitus, and blurred vision, which resolved post-surgery, suggest possible ICP fluctuations despite a normal measurement. This highlights that subjective symptoms and indirect signs of ICP should not be dismissed in craniosynostosis late diagnosis cases, even with normal ICP readings.

Furthermore, the patient’s pre-existing dyspraxia and ADHD, alongside improvements in neurobehavioral function post-surgery, support the growing body of evidence linking sagittal synostosis to neurocognitive and neurobehavioral impairments. While global IQ may be within the average range in older children with sagittal synostosis, specific deficits in attention, coordination, and learning can be prevalent. This case suggests that early developmental delays in infancy may manifest as more specific neurobehavioral challenges as children age. The dramatic improvement in the patient’s hyperactivity post-surgery and the resolution of dyspraxia point towards a potential link between craniosynostosis and these conditions, warranting further investigation.

The psychosocial impact of scaphocephaly in craniosynostosis late diagnosis should not be underestimated. Bullying and self-esteem issues become increasingly relevant as children become more aware of appearance differences, typically around age seven. Earlier intervention could potentially mitigate these psychosocial challenges associated with the visible cranial deformity.

Success of Surgery in Craniosynostosis Late Diagnosis

Despite the patient’s older age at the time of surgery, the cranial vault remodeling was remarkably successful. While surgery is typically performed in younger children to leverage rapid skull growth for optimal remodeling and re-ossification, this case demonstrates that significant benefits are achievable even in older children with craniosynostosis late diagnosis. The surgery effectively normalized the cephalic index and corrected the cranial deformity.

Figure 4: Posterior view comparison. (A) Pre-operative image, showing occipital protrusion. (B) Post-operative image, demonstrating a more balanced posterior skull contour after surgery.

The improvement in neurocognitive function further supports the hypothesis that surgical intervention, even in craniosynostosis late diagnosis, can positively impact neurobehavioral development. While research suggests a potential correlation between earlier surgery and cognitive outcomes, this case indicates that benefits are not limited to early intervention.

The patient’s immediate post-operative vision improvement also raises intriguing questions about the link between sagittal synostosis and visual function. While craniosynostosis is associated with various visual impairments, the specific impact of sagittal synostosis and the potential for late surgical intervention to improve vision require further research. This case suggests that even in craniosynostosis late diagnosis, surgical correction can positively influence visual acuity.

Conclusions

This case of craniosynostosis late diagnosis provides crucial learning points for healthcare professionals and families. It highlights that sagittal synostosis can present without clear risk factors or elevated ICP, emphasizing the importance of vigilance in recognizing scaphocephaly at any age. Delayed diagnosis can lead to neurobehavioral and visual impairments, as well as psychosocial difficulties. However, this case powerfully demonstrates that cranial vault remodeling in craniosynostosis late diagnosis, even in older children, can be highly effective in normalizing head shape, improving vision, preventing further neurobehavioral underdevelopment, and enhancing self-esteem. This underscores the value of considering surgical intervention even when craniosynostosis is diagnosed later in childhood.

Acknowledgments

With thanks to the Oxford Craniofacial Unit.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived for all participants in this study.