Psychosis, characterized by a disturbed perception of reality, presents a significant challenge in primary care settings. It’s crucial for primary care physicians (PCPs) to confidently approach patients exhibiting psychotic symptoms. Have you ever found yourself questioning the origins of psychosis in a patient? Are you sometimes unsure how to distinguish between biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors contributing to this complex condition? Do you seek clarity on which aspects of patient history, physical examinations, and laboratory tests are most effective in determining the underlying cause and guiding appropriate treatment strategies? If these questions resonate with you, this article provides a comprehensive guide to aid in the recognition and differential diagnosis of psychosis within the primary care context.

Understanding Acute Psychosis: Definition and Key Features

The term “psychosis” has evolved in its definition across medical and psychological disciplines. Initially, it underscored the functional impairments stemming from a compromised ability to perceive and interpret reality accurately. More recently, psychosis is understood as a clinical syndrome encompassing hallucinations, delusions, disorganized behavior or speech, or a combination of these manifestations. Notably, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), while outlining diagnostic criteria for various psychotic disorders, does not offer a standalone definition of psychosis. To effectively address acute psychosis, it’s essential to define its core components.

Hallucinations are sensory experiences that occur without external stimuli or corresponding somatic triggers. In the context of psychosis, these perceptions are characterized by a lack of insight, meaning the individual does not recognize them as unreal or internally generated. Examples include auditory hallucinations, such as hearing voices instructing self-harm, or visual hallucinations, like seeing animals in the room when none are present.

Delusions are firmly held, improbable beliefs that are resistant to logical reasoning and contradictory evidence, diverging significantly from shared beliefs within the individual’s culture. Delusions can manifest in various forms, including persecutory delusions (belief of being targeted), grandiose delusions (belief of exceptional importance or abilities), erotomanic delusions (belief that another person, often of higher status, is in love with them), or religious delusions (belief of having a special religious identity or mission).

Disorganized thought and speech are characterized by disruptions in the logical flow of thinking, often evident in speech patterns. This can include incoherent speech, tangential responses that deviate from the topic, or illogical content. Disorganized behavior encompasses psychomotor disturbances like unusual postures or movements and, in severe cases, catatonia, a state of marked motor abnormality.

Acute psychosis is defined as the emergence of these symptoms – hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thoughts or behaviors – within a short timeframe, typically less than one month. The DSM-5 defines brief psychotic disorder by the presence of psychotic symptoms lasting between one day and one month, provided these symptoms are not attributable to other medical or substance-induced conditions. This duration distinguishes it from schizophreniform disorder, which requires symptoms to persist for one to six months. The International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) equivalent, acute and transient psychotic disorders (ATPD), emphasizes a rapid onset within two weeks, fluctuating psychotic symptoms, and the potential presence of an acute stressor preceding the onset.

Differential Diagnosis: Unpacking the Causes of Psychosis

The differential diagnosis of psychosis can be broadly categorized into three primary domains: psychiatric, medical, and drug-induced causes.

Psychiatric causes encompass a range of mental health conditions including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder with psychotic features, delusional disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, and postpartum psychosis. While the precise neurobiological underpinnings of these conditions remain under investigation, each is recognized as a distinct psychiatric entity with specific diagnostic criteria.

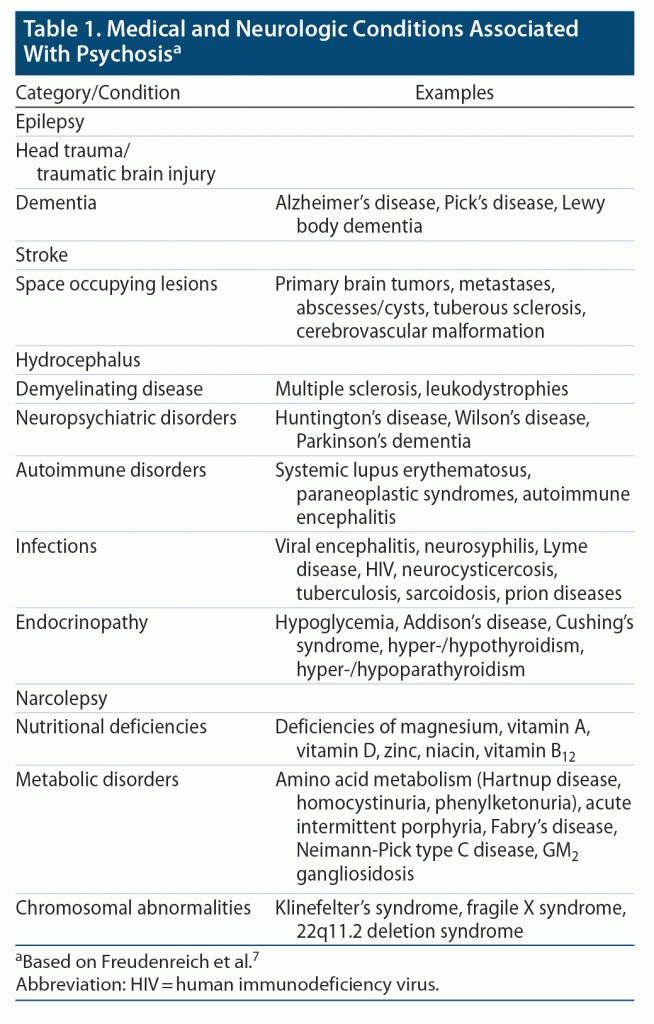

Table 1 provides a detailed overview of medical and neurological conditions that can trigger psychosis. Medical causes include delirium, hypoxia, dysglycemia (both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia), autoimmune disorders like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), neurological conditions such as Lewy body dementia and Wilson’s disease, infections (sepsis, urinary tract infections particularly in older adults), endocrine disorders (Cushing’s disease, hyperthyroidism), paraneoplastic syndromes (anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian cancer), vitamin deficiencies (thiamine, niacin, cobalamin), and metabolic and electrolyte imbalances (hypercalcemia, hepatic encephalopathy, uremia). Delirium, a frequent cause of altered mental status in hospitalized patients, is crucial to consider. It’s defined as an acute disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition caused by an underlying medical condition, not better explained by pre-existing neurocognitive disorders. Management of delirium and other secondary psychoses centers on prevention when possible (maintaining nutrition, sleep hygiene, judicious use of psychoactive medications) and supportive care alongside treatment of the underlying medical condition.

Table 1: Medical and Neurological Conditions Associated with Acute Psychosis. This table lists various medical and neurological conditions that can manifest with psychotic symptoms, aiding in the differential diagnosis of psychosis in primary care.

Drug-induced psychoses, while technically secondary psychoses, warrant separate consideration due to the critical need to assess for substance use, both recreational and iatrogenic, during psychosis evaluation. Recreational substances known to induce psychosis include cocaine, alcohol, amphetamines, LSD, cannabis, phencyclidine, ketamine, and inhalants. Table 2 offers a more comprehensive list. Iatrogenic causes involve medications like anticholinergics, antiarrhythmics, steroids, antiviral agents, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, dextromethorphan, antihistamines, and antidepressants (in cases of SSRI-induced mania in bipolar disorder patients). Furthermore, withdrawal syndromes from substances like alcohol and benzodiazepines can also precipitate psychotic symptoms.

Table 2: Substances Associated with Acute Psychosis. This table provides a list of various substances, both recreational and prescription, that are known to be associated with the development of acute psychosis, highlighting the importance of substance use history in the differential diagnosis.

A thorough differential diagnosis of acute psychotic symptoms necessitates considering all these potential etiologies. By keeping these categories in mind, clinicians can strategically tailor their history taking, physical examinations, and laboratory investigations to arrive at an accurate diagnosis and develop an effective management plan for acute psychosis.

History Taking: Key Aspects for Differential Diagnosis and Workup

Psychosis can be broadly classified as primary (originating from a psychiatric illness) or secondary (“organic,” due to delirium, dementia, drugs/toxins, or medical illnesses). Several historical factors are critical in distinguishing between these categories and refining the differential diagnosis. These include the symptom timeline, patient age, prior psychiatric and medical history, concurrent symptoms, and family history. Table 3 further details these aspects.

Table 3: Historical Aspects Important for Diagnosis of Acute Psychosis. This table summarizes key historical factors that are crucial to consider when diagnosing acute psychosis, helping to differentiate between primary psychiatric and secondary organic causes.

The timeline of symptoms is particularly informative. Acute onset psychosis, developing over hours to days, is suggestive of an organic etiology such as encephalitis, endocrinopathy, or stroke (refer to Table 1 for medical and neurological causes). When investigating potential organic causes, the temporal relationship between symptom onset and new medications, dose changes, substance use or withdrawal must be carefully examined (see Table 2 for substances and medications linked to psychosis). Conversely, chronic symptoms, persisting for months, are more indicative of a primary psychiatric illness. For example, a prodromal phase of non-specific psychiatric symptoms and functional decline, followed by a gradually developing psychosis over weeks to months, is characteristic of schizophrenia.

Patient age is another critical factor. Primary psychiatric illnesses with psychotic features typically emerge in adolescence and young adulthood. In these age groups, primary psychiatric causes should be prioritized in the differential diagnosis. However, in young children and older adults, primary psychiatric causes are less likely, making delirium, dementia, and other medical or neurological causes more probable etiologies. In very young children, metabolic disorders and chromosomal or genetic abnormalities also need consideration.

The patient’s prior medical and psychiatric history is essential. As outlined in Table 1, numerous medical conditions can cause psychotic symptoms (e.g., autoimmune disorders, thyroid disorders, hypoglycemia). Neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders such as dementia, Huntington’s disease, and Wilson’s disease can also trigger psychosis. A history of such illnesses known to induce psychosis should raise their suspicion in the differential. Similarly, many psychiatric illnesses (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder) can manifest with psychotic symptoms. Finally, a history of substance use, especially of substances known to induce psychosis, is a vital consideration. While a prior illness does not automatically imply causality, it significantly shapes the differential diagnosis.

Concurrent symptoms accompanying psychosis provide valuable clues. Physical symptoms like weight loss, fever, or rash suggest an underlying organic illness. Specific symptom constellations can point towards particular illnesses; for instance, malar rash, fatigue, and joint pain are suggestive of SLE. Neurological symptoms like abnormal movements, seizures, focal deficits, or sensory changes indicate a neurological etiology. Mood symptoms (depression or mania) or negative symptoms (flat affect, alogia, asociality) are often associated with primary psychiatric illnesses.

Understanding the patient’s family history further refines the differential diagnosis. A family history of psychiatric illnesses associated with psychosis (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) increases the likelihood of these conditions. Similarly, a family history of neurological illnesses associated with psychosis (Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Wilson’s disease) also raises their probability.

Physical Examination: Essential Components in Acute Psychosis

A comprehensive physical and neurological examination is paramount in all patients presenting with acute onset psychotic symptoms. Table 4 provides further details.

Table 4: Physical Exam Findings in Acute Psychosis. This table outlines key aspects of the physical examination that are particularly relevant in patients presenting with acute psychosis, aiding in the identification of potential underlying medical or neurological causes.

Vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation) are crucial. Abnormalities often suggest an underlying medical etiology. The physical examination should focus on signs and symptoms that could indicate a medical diagnosis. Pupillary size (dilated or constricted) can suggest substance use or withdrawal. Aberrant pupillary function may indicate a central nervous system (CNS) lesion, a genetic disorder, or neurosyphilis (Argyll-Robertson pupil). Skin examination is also informative; dermatological findings like malar rash in SLE, dermatitis in pellagra (niacin deficiency), or the bull’s-eye rash of Lyme disease can be indicative. Co-occurring findings like optic neuritis (eye pain and blurry vision), neuropathy, and muscle weakness may suggest multiple sclerosis.

A thorough neurological examination is essential, including assessment of cranial nerves, sensory and motor function, deep tendon reflexes, cerebellar function, and gait. Focal neurological findings suggest specific etiologies such as acute stroke, Parkinson’s disease, or Wilson’s disease.

Bedside assessment of cognitive function is critical. Deficits in orientation, attention, or memory often point towards delirium or dementia.

Laboratory Testing: Guiding the Diagnostic Process in Acute Psychosis

Laboratory testing in acute psychosis should be broad, encompassing major medical causes of psychotic symptoms. Table 5 provides a list of recommended tests.

Table 5: Laboratory Testing in Acute Psychosis. This table lists recommended laboratory tests for patients presenting with acute psychosis to screen for underlying medical conditions that could be contributing to their symptoms.

Minimum laboratory investigations should include a complete blood count (CBC) with differential, chemistry panel (including calcium and glucose), liver function tests (LFTs), thyroid function tests (TFTs), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), vitamin B12 and folate levels, HIV test (recommended as routine care), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-abs) test for syphilis, relevant serum drug levels (e.g., digoxin, alcohol), serum and/or urine drug screen, and urinalysis. While ceruloplasmin levels are sometimes considered for Wilson’s disease, they can yield false positives and may be of limited utility. Results must be interpreted within the clinical context, as positive results do not automatically establish causality.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in acute psychosis is debated, as incidental findings occur at similar rates in patients and controls. However, given the long-term impact of untreated psychosis and the potential to rule out organic causes, MRI may be cost-effective.

There is no single, universally recommended, evidence-based screening panel. The listed tests are an example, not exhaustive. Further testing is warranted if initial workup is inconclusive or atypical symptoms are present. For example, lumbar puncture (LP) with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis should be performed if CNS infection or autoimmune encephalitis is suspected. Electroencephalogram (EEG) can aid in diagnosing seizure disorders or confirming delirium. Chest x-ray and blood cultures are indicated if infection is a concern.

Distinguishing Biological, Psychological, and Sociocultural Etiologies

Acute psychosis can be triggered by biological, psychological, or sociocultural factors; however, the precise etiology is often multifactorial and complex. Biological etiologies can stem from primary psychiatric disorders or secondary medical conditions (e.g., anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, Huntington’s disease). Table 6 helps differentiate primary psychiatric disorders from secondary psychoses.

Table 6: Differentiating Primary Psychiatric Disorders from Secondary Psychoses. This table provides a comparative overview of features that can help distinguish between primary psychiatric disorders and secondary psychoses, assisting primary care physicians in their differential diagnosis.

Patients with primary psychiatric illnesses are typically younger, experience insidious onset of psychosis (often with auditory hallucinations), and may have premorbid symptoms (mood changes, neurocognitive impairments). Psychosis lasting over six months with significant functional deficits (e.g., interpersonal withdrawal) is a hallmark of schizophrenia. Prodromal symptoms like unusual perceptions or odd thoughts may precede full psychosis in schizophrenia and should be recognized by PCPs as early indicators. The presence of mood disturbance alongside psychotic features can differentiate schizoaffective disorder from schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder. Delusional disorder is diagnosed when non-bizarre delusions (misinterpretations of perceptions or experiences) persist for over a month without other prominent schizophrenia features.

As detailed in Table 1, medical conditions (neurological, substance-related, autoimmune, drug-induced) are associated with psychosis onset. Psychosis due to a medical condition often presents with abnormal vital signs, laboratory findings, altered consciousness or cognition, or visual hallucinations. In emergency settings, psychosis is a common feature of delirium in older adults. Careful attention to cognitive deficits (orientation, memory, language), symptom timeline, systemic disorder signs, and information from collateral sources is crucial in differentiating dementia from other conditions. Substance-related disorders are the most common cause of acute psychosis in adolescents and young adults. Recognizing sudden onset psychosis with drug abuse or withdrawal symptoms helps differentiate substance-induced psychosis from other secondary causes. A thorough medication history (including antipsychotics, herbal, over-the-counter, and recreational drugs) is essential to rule out drug-induced psychosis from specific medical conditions.

Psychological etiologies are also significant. Epidemiological studies consistently show stress as a key factor in psychosis onset. Brief psychotic disorders are often triggered by stressful events (trauma, loss, childbirth). These disorders are characterized by shorter symptom duration and recovery within a month. Postpartum psychosis, a brief psychotic episode during pregnancy or within four weeks postpartum, can occur, often with hallucinations related to harming the baby. Sociocultural factors (poverty, migration, discrimination, lack of social support) are also linked to psychosis onset. Recognizing these etiologies allows PCPs to initiate timely psychiatric interventions.

Risk Factors and Prevalence of Acute Psychosis

A combination of biological factors (sex, genetics, family history) increases baseline risk for acute psychosis. Nearly one-third of children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome develop psychosis, often by early adulthood. For those biologically predisposed, sociodemographic, behavioral, and medical factors can trigger episodes. Stressors like physical stress (binge drinking, poor diet, sleep problems), environmental stress (lack of support, migration, life changes), emotional stress (relationship difficulties), or acute life events (bereavement, childhood abuse) increase risk. Exposure to psychotropic drugs (amphetamines) and cannabis can also increase vulnerability and potentially trigger earlier onset.

In the general population, lifetime prevalence of any psychotic disorder is ~3%, with 0.21% developing secondary psychosis due to medical conditions. Schizophrenia and related disorders affect ~1%. Lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder is 0.5%–4.3% in primary care and 9.3% in bipolar spectrum illness. Delusional disorders are less frequent (DSM-5 prevalence = 0.02%), more common in women. Brief psychotic disorder is uncommon, twice as frequent in women. Postpartum psychosis affects 1 in 500-1,000 women post-childbirth; risk factors include personal or family history of bipolar disorder or previous psychosis. Psychotic symptoms are frequent among illicit substance users, prevalence depending on context of use/withdrawal and showing a dose-response relationship with severity of drug use.

Treatment and Management Strategies for Acute Psychosis

Symptomatic treatment of acute psychosis may be necessary before establishing the underlying etiology. Treatment approaches vary based on symptom severity and presumed cause. Table 7 outlines different treatment approaches, and Table 8 highlights patient factors influencing initial treatment. Pharmacological and psychosocial interventions are the cornerstones of psychosis treatment.

Table 7: Treatment Approaches for Patients with Acute Psychosis. This table summarizes various treatment approaches for managing acute psychosis, ranging from pharmacological interventions to psychosocial support, tailored to the patient’s needs and symptom severity.

Antipsychotic medications are the mainstay for acute psychosis, most effective for positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions, agitation) and less so for negative or cognitive symptoms. Atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics (risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole, lurasidone) are generally preferred over typical (first-generation) antipsychotics (haloperidol, perphenazine, chlorpromazine) due to lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and tardive dyskinesia (TD).

Antipsychotic selection is based on patient history and side effect profiles. Aripiprazole and risperidone are often initial choices due to favorable profiles. Olanzapine may be beneficial for agitation due to sedation, and quetiapine for insomnia. Patients with cardiac history or cardiovascular risk factors should avoid antipsychotics with metabolic side effects (clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine) and QTc prolongation risk (ziprasidone, haloperidol, quetiapine). Elderly patients should avoid anticholinergic medications (olanzapine, quetiapine, clozapine), and antipsychotics may be contraindicated in dementia-related psychosis or catatonia. Clozapine, a second-generation antipsychotic, is reserved for treatment-resistant cases due to potential life-threatening side effects. Augmentation with mood stabilizers (lithium, valproic acid) is also an option. Polypharmacy with multiple antipsychotics is common but lacks strong evidence. Antipsychotics have short-term (involuntary movements, sedation, weight gain, constipation) and long-term (TD, metabolic side effects) adverse effects, which should be discussed with patients. Rare but serious risks include agranulocytosis and myocarditis, especially with clozapine. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is effective for treatment-resistant psychosis. Shared decision-making improves adherence and outcomes.

Agitated psychosis is a medical emergency. Patient and safety of others is paramount. Outpatient agitation may require transfer to a safe setting. Management involves behavioral de-escalation and sedating antipsychotics (olanzapine or risperidone disintegrating tablets, oral haloperidol). Intramuscular (IM) olanzapine or IM haloperidol (with or without benzodiazepine like lorazepam) can be used if oral medication is refused. IM haloperidol carries EPS risk, often given with benztropine or diphenhydramine. Physical restraints may be necessary in severe agitation, but carry physical and psychological risks.

Once stabilized, pharmacotherapy should be coupled with psychosocial interventions to aid recovery. Psychosocial treatments help cope with positive symptoms and can reduce negative and cognitive symptoms. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, cognitive remediation therapy, and family therapy are effective. Psychosocial skills training and community-based services are helpful for chronic psychosis.

Follow-Up Care After Initial Assessment

Close follow-up is crucial after initial assessment and treatment initiation. Depending on symptom severity, etiology, and nature, follow-up may involve a psychiatrist, mental health professional, PCP, and specialists (neurologists, rheumatologists, endocrinologists, infectious disease doctors). Multidisciplinary treatment improves outcomes. Etiology may not be immediately clear, necessitating review of lab and imaging results. Symptom monitoring during acute and maintenance phases is essential. Follow-up includes assessment of safety risks, symptom changes, collateral information, physical and mental status exam, substance withdrawal consideration, and risk-benefit discussions. Once stabilized, reassessment of positive and negative symptoms, cognition, and quality of life is important. Monitoring short- and long-term antipsychotic side effects is necessary for adherence and outcomes. Follow-up with psychosocial skill trainers, rehabilitation practitioners, social workers, and psychotherapists is crucial, especially for chronic psychosis.

Case Vignette Resolution: Ms. E’s Journey

The ED physician considered medical, neurological, and psychiatric causes for Ms. E’s psychosis. Blood tests (CBC, electrolytes, glucose, LFTs, TFTs, B12, folate, ESR, ANA, FTA-abs, HIV, toxicology, urinalysis) and MRI were normal, ruling out medical and neurological etiologies. Vital signs and physical/neurological exams were also unremarkable. Psychiatry consultation was requested.

The psychiatrist learned Ms. E lost her waitress job due to mistakes and odd comments about contaminated food. She had become increasingly withdrawn, worried about apartment break-ins and gasoline smells, and was experiencing auditory hallucinations. Mental status exam showed alertness, orientation, and intact memory, but paranoia and auditory hallucinations were present. Suicidal/homicidal ideation was denied, but insight was lacking.

Schizophreniform disorder was the most likely diagnosis. Ms. E was admitted to inpatient psychiatry, started on aripiprazole with symptom improvement, and discharged to outpatient psychiatric care after two weeks.

Conclusion: Navigating the Complexities of Acute Psychosis in Primary Care

New-onset psychotic symptoms pose significant challenges for patients, families, and healthcare providers. Understanding the biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors underlying psychosis is crucial for effective evaluation and treatment. Since treatment hinges on etiology, determining the nature, time course, and severity of symptoms, and differentiating between primary psychiatric conditions and medical/neurological illnesses is essential. This requires thorough interviews, physical/neurological examinations, laboratory testing, and brain imaging. A collaborative treatment approach and diligent monitoring of symptoms and side effects optimize patient outcomes.

Clinical Points

- Psychotic disorders are broadly categorized as primary psychiatric conditions or secondary psychoses due to medical, neurological, substance-related, or other identifiable causes. However, the underlying cause is often complex and uncertain.

- Differential diagnosis requires understanding symptom timeline, patient age, past medical/psychiatric history, concurrent symptoms, and family history.

- Thorough physical and neurological examination (including mental status/cognitive exam), and laboratory testing (CBC, electrolytes, BUN/creatinine, LFTs, TFTs, ESR, FTA-abs, ANA, vitamin B12/folate, MRI, EEG, HIV testing) are critical for acute onset psychosis.

- After stabilization (often with antipsychotics), reassessment of positive and negative symptoms, cognitive function, and quality of life is essential for recovery and improved outcomes.