Chronic diarrhea, defined as diarrhea persisting for four weeks or more, is a prevalent condition affecting up to 5% of the global population, irrespective of age, gender, ethnicity, or socioeconomic background. This condition significantly impacts patients’ well-being and daily life, posing substantial economic burdens on healthcare systems due to diagnostic and management complexities. The range of potential causes for chronic diarrhea is extensive, encompassing infectious agents, endocrine disorders, malabsorption syndromes, and gut-brain interaction disorders. The overlapping nature of symptoms across these diverse conditions often complicates accurate diagnosis, potentially leading to diagnostic delays or misdiagnosis. This review delves into the differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhea, with a particular focus on Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea (IBS-D) and Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI). These two conditions, while sharing similar symptoms, stem from distinct underlying mechanisms and necessitate markedly different management strategies. We present a structured four-step diagnostic approach and a practical algorithm designed to aid clinicians in effectively distinguishing IBS-D from EPI and other etiologies of chronic diarrhea. Our aim is to enhance diagnostic precision, ultimately improving patient outcomes, quality of life, and reducing the economic strain on healthcare resources.

Key Words: Differential Diagnosis Chronic Diarrhea, diarrhea, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea, IBS-D, EPI

Chronic diarrhea, lasting longer than four weeks, affects a significant portion of the population, approximately 5%, across all demographics. Global surveys underscore the widespread nature of functional diarrhea, with nearly 5% of individuals reporting symptoms. The impact of chronic diarrhea extends beyond physical discomfort, significantly diminishing health-related quality of life, disrupting daily routines, and escalating healthcare utilization. In the United States alone, gastrointestinal issues, including diarrhea, account for millions of ambulatory visits annually, highlighting the substantial healthcare burden associated with these conditions.

The differential diagnosis for chronic diarrhea is broad, encompassing a wide array of conditions. These include infections from bacteria, parasites, and viruses, endocrine disorders such as hyperthyroidism and diabetes, maldigestive and malabsorptive conditions like celiac disease, lactose intolerance, and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI), and disorders of gut-brain interaction, notably irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Inflammatory conditions such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, medication side effects (e.g., laxatives), and toxic substance ingestion (e.g., alcohol abuse) also contribute to the differential diagnosis. The considerable overlap in symptoms among these conditions often presents diagnostic challenges. This symptom similarity can result in delayed or incorrect diagnoses, leading to persistent symptoms and adverse health outcomes for patients. Therefore, accurate and timely diagnosis is paramount for effective management.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of diagnostic strategies for chronic diarrhea, emphasizing the differentiation of IBS-D and EPI from other conditions presenting with similar symptoms. By focusing on the distinct features of IBS-D and EPI, we aim to equip clinicians with the knowledge to facilitate earlier and more accurate diagnoses. This, in turn, can lead to more targeted treatments, improved patient quality of life, and a reduction in healthcare resource utilization.

Understanding Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea (IBS-D)

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) stands as the most common cause of diarrhea in developed countries, with prevalence rates ranging from 4% to 9% in the United States, based on Rome IV criteria. While IBS can manifest at any age, it is most frequently diagnosed in women between 20 and 40 years old, with women being approximately twice as likely as men to receive an IBS diagnosis.

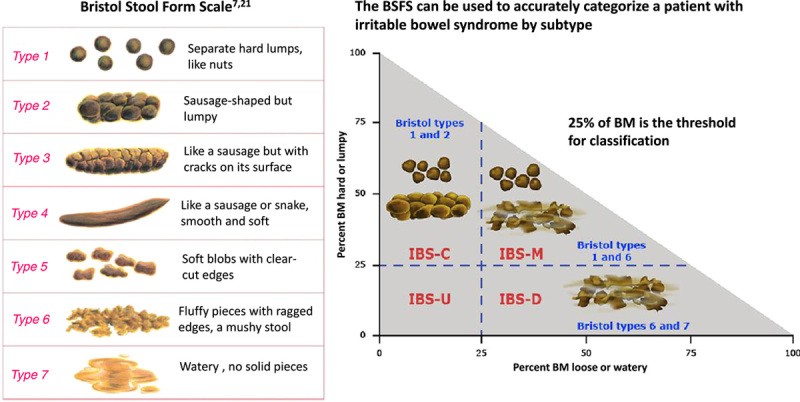

The Rome IV diagnostic criteria for IBS hinge on the presence of recurrent abdominal pain, occurring on average at least one day per week. This pain must be associated with changes in bowel habits, specifically related to defecation and/or alterations in stool form or frequency. Furthermore, these symptoms must significantly impact a patient’s quality of life and ability to perform daily activities. While the Rome IV criteria do not stipulate a specific symptom duration for clinical diagnosis, clinicians must ensure that other potential diagnoses have been adequately excluded. The research-focused Rome IV criteria are stricter, requiring symptoms to be present for the preceding three months with symptom onset at least six months prior to diagnosis (refer to Table 1). Common symptoms in IBS-D, beyond the core diagnostic criteria, include abdominal bloating and distension, fecal urgency, a sensation of incomplete evacuation, and mucus passage in stools. Stool consistency is typically watery, classified as type 6 or 7 on the Bristol Stool Form Scale (Figure 1), and bowel movements predominantly occur during waking hours. Psychological stress is a recognized contributing factor. It is crucial to note that certain ‘red flag’ symptoms necessitate further investigation for organic causes of diarrhea beyond IBS. These alarm features include symptom onset after age 50, unintentional weight loss, acute changes in symptom patterns, recurrent rectal bleeding or anemia, and a family history of inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, or colorectal cancer (Figures 2 and 3).

TABLE 1. Rome IV Diagnostic Criteria for Irritable Bowel Syndrome

| Clinical Diagnostic Criteria | Research Diagnostic Criteria |

|---|---|

| Recurrent abdominal pain on average at least 1 day/week, associated with two or more of the following: • Related to defecation • Associated with a change in frequency of stool • Associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool Bothersome symptoms that: • Interfere with daily activities • Require attention • Cause worry or interfere with quality of life | Recurrent abdominal pain on average at least 1 day/week in the last 3 months, associated with two or more of the following: • Related to defecation • Associated with a change in frequency of stool • Associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool Symptoms onset at least 6 months before diagnosis. |

*For the last 8 weeks.

†For the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis.

FIGURE 1. Bristol Stool Form Scale and IBS Subtypes

Alt text: Bristol Stool Form Scale illustrating stool types 1 through 7, ranging from constipation to diarrhea, and their association with IBS subtypes: IBS-C, IBS-D, IBS-M, and IBS-U.

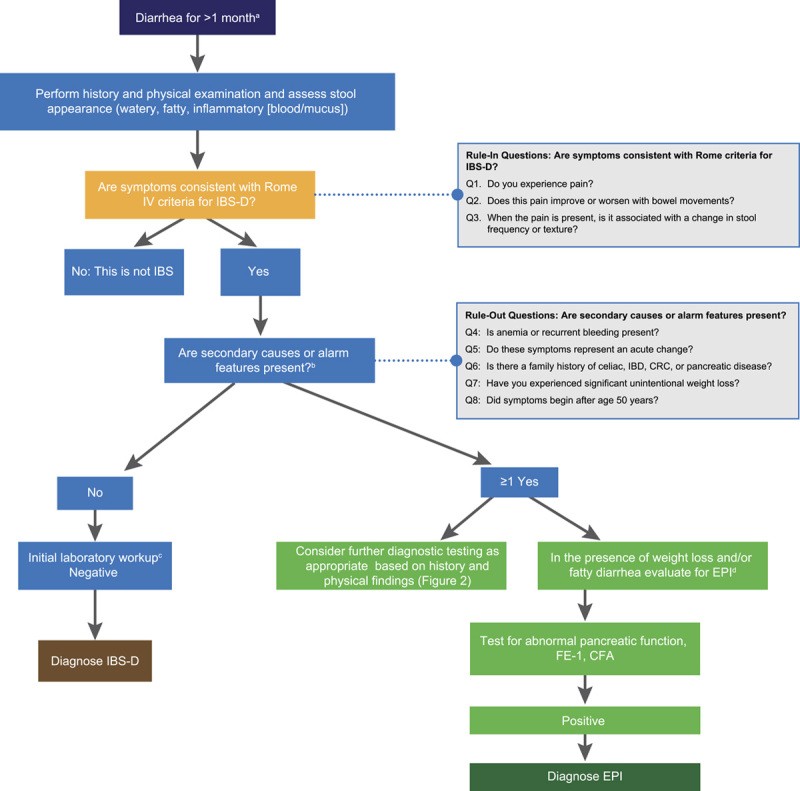

FIGURE 2. General Sequence for Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Diarrhea

Alt text: Flowchart outlining a general sequence for differential diagnosis of chronic diarrhea, starting with history and physical exam, followed by alarm feature assessment, initial lab workup, and further investigations for conditions like celiac disease, IBD, and EPI.

FIGURE 3. A General Strategy for the Differential Diagnosis of Patients with Chronic Diarrhea: EPI or IBS-D?

Alt text: Algorithm illustrating a diagnostic strategy for chronic diarrhea, focusing on differentiating between EPI and IBS-D, incorporating alarm features, initial tests like CBC, CRP, fecal calprotectin, and FE-1, and guiding further investigations based on risk factors and test results.

While chronic abdominal pain is a defining symptom differentiating IBS from functional diarrhea, significant symptom overlap exists between these conditions, and patients may transition between diagnoses. Patients with IBS, particularly those experiencing frequent pain, often exhibit increased psychological distress and somatic comorbidities compared to individuals with functional diarrhea, necessitating appropriate evaluation and management. Early intervention for these overlapping conditions can be beneficial.

Currently, no universally accepted biomarker exists for IBS diagnosis. Extensive testing to rule out organic causes is generally discouraged due to its high cost, inefficiency, and low diagnostic yield. In most cases, an accurate IBS diagnosis can be established based on a detailed patient history alone. Studies have demonstrated that Rome criteria, in the absence of alarm symptoms, exhibit high specificity and positive predictive values for IBS diagnosis. Consequently, clinical guidelines recommend minimizing extensive diagnostic investigations and adopting a positive diagnostic approach for IBS. Major gastroenterology organizations advise against routine colonoscopy for IBS diagnosis, except for age-appropriate screening in individuals over 45 or in the presence of warning signs suggestive of more serious underlying conditions.

Recommended diagnostic tests for IBS are limited. They typically include serologic testing to exclude celiac disease (serum IgA and tissue transglutaminase IgA), fecal calprotectin (or lactoferrin) and C-reactive protein to rule out inflammatory bowel disease in patients without alarm features, and Giardia stool antigen testing for individuals with relevant risk factors such as travel to endemic regions or exposure to contaminated water sources.

IBS Subtypes and IBS-D

IBS is further categorized into four subtypes based on predominant stool patterns: IBS with constipation (IBS-C), IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), mixed IBS (IBS-M), and unsubtyped IBS (IBS-U). Among these, IBS-D is the most prevalent subtype, affecting up to 40% of adults diagnosed with IBS. Globally, IBS-D affects approximately 1.2% of the population, with a slight female predominance, mirroring the overall IBS prevalence pattern.

Patients with IBS-D characteristically produce Bristol Stool Form Scale type 6 or 7 stools (loose, mushy, or watery) in more than 25% of bowel movements and type 1 or 2 stools (hard or lumpy) less than 25% of the time (Figure 1). Rome IV diagnostic criteria emphasize assessing stool texture on days with abdominal pain to enhance the precision of IBS subtype classification.

The symptom overlap between IBS-D and other conditions such as EPI, celiac disease, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), disaccharidase deficiencies, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and infections can complicate diagnosis. However, initial stool characterization—watery (suggestive of IBS), fatty or greasy (suggestive of EPI), or inflammatory (suggestive of inflammatory bowel disease)—can serve as a valuable first step in narrowing the differential diagnosis (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Narrowing the Diagnosis According to Stool Characteristics

| Watery Diarrhea | Fatty/Greasy Diarrhea | Inflammatory Diarrhea |

|---|---|---|

| Osmotic: • Carbohydrate malabsorption • Celiac disease • Osmotic laxatives Secretory: • Bile acid malabsorption • Microscopic colitis • Endocrinopathies (e.g., diabetes, hyperthyroidism) • Medications (e.g., metformin) Functional: • Functional diarrhea • Irritable bowel syndrome | Malabsorption or Maldigestion: • Celiac disease • Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth • Giardiasis • Whipple disease • Inadequate luminal bile acid concentration • Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency | Inflammatory Bowel Disease: • Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis (SCAD) • Infectious disease • Clostridium difficile • Invasive bacterial infections • Invasive parasitic infections • Ischemic colitis • Radiation colitis • Lymphoma |

Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI) and Chronic Diarrhea

Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI) arises from a deficiency in pancreatic enzyme secretion, leading to impaired digestion. While primarily associated with pancreatic diseases, EPI can also result from various extrapancreatic conditions. A significant proportion of children with cystic fibrosis develop EPI early in life, and a considerable percentage of patients with chronic pancreatitis, particularly severe cases, will experience EPI. Pancreatic cancer is also strongly linked to EPI, especially when tumors are located in the pancreatic head. In pancreatic diseases, reduced enzyme and bicarbonate secretion stems from parenchymal damage and/or obstruction of the pancreatic duct.

EPI is characterized by insufficient pancreatic enzyme activity in the intestinal lumen, resulting in maldigestion, particularly of fats. Diarrhea in EPI develops when dietary intake overwhelms the digestive capacity of the pancreas. Symptom presentation in EPI is highly variable, influenced by dietary habits and restrictions. Clinically evident steatorrhea (fatty, oily stools), a hallmark of EPI, is reported in a significant proportion of patients with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. A detailed patient history, including dietary habits, is crucial, as low-fat diets adopted to manage symptoms can mask EPI and delay diagnosis.

Patients with EPI typically present with symptoms of malabsorption syndrome, including diarrhea, abdominal distension and cramps, flatulence, and weight loss, along with nutritional deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins, micronutrients, and proteins. Symptoms vary depending on the underlying cause, enzyme deficiency severity, and dietary fat intake, but commonly include foul-smelling, fatty, loose stools, flatulence, and weight loss. Long-term consequences of EPI can be severe, including sarcopenia, osteoporosis, metabolic bone disease, increased infection risk, and cardiovascular disease.

EPI should be considered in patients with chronic diarrhea who have a history of pancreatic disease (acute, relapsing, or chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, pancreatic cancer, diabetes mellitus type 3c), risk factors for pancreatic disease (alcohol abuse, smoking), a family history of pancreatic diseases, or a history of pancreatic or gastric surgery. In the absence of these risk factors, EPI testing should be reserved for patients with a high clinical suspicion.

Definitive EPI diagnosis is crucial to prevent complications but can be challenging due to limitations in diagnostic tests. Diagnosis typically involves a combination of symptom assessment, nutritional marker evaluation, and noninvasive pancreatic function tests, such as the coefficient of fat absorption (CFA) and fecal elastase-1 (FE-1) tests. While other pancreatic function tests exist, many are invasive or not readily available. The direct secretin-cholecystokinin (CCK) test, although highly sensitive, is invasive and cumbersome, limiting its clinical utility for routine EPI diagnosis.

The CFA test is considered the gold standard for EPI diagnosis. However, it requires strict dietary fat intake and comprehensive fecal collection, making it impractical for routine clinical use due to poor patient compliance. 13C-labeled breath tests offer a more patient-friendly alternative to CFA but are not yet widely accessible. The FE-1 test, measuring fecal concentration of pancreatic elastase, is a simple, noninvasive, and widely available pancreatic function test. It is the most frequently used test for assessing pancreatic exocrine function. However, the optimal cutoff and accuracy of FE-1 for EPI diagnosis vary, with reported sensitivities and specificities ranging considerably depending on the chosen cutoff values and study populations.

In patients with chronic diarrhea and a high pre-test probability of EPI (e.g., pancreatic cancer, advanced chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic surgery), pancreatic function tests may be of limited additional value for diagnosis. Conversely, in patients with chronic diarrhea and a low probability of EPI (no pancreatic disease history, no risk factors, absence of weight loss or nutritional deficiencies), normal FE-1 levels can effectively exclude EPI. Low FE-1 levels, however, while suggestive of EPI, can also be false positives, particularly in watery diarrhea, and warrant further pancreatic investigation to rule out underlying pancreatic disease.

EPI is recognized as one of several organic gastrointestinal diseases that can mimic IBS. Studies have shown that EPI, defined by low FE-1, is present in a small but significant percentage of patients meeting Rome criteria for IBS-D or presenting with unexplained abdominal pain and diarrhea. However, due to the possibility of false-positive FE-1 results in watery diarrhea, a low FE-1 level alone does not definitively exclude IBS-D.

Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Diarrhea: A Step-by-Step Approach

Accurate and timely diagnosis is critical for effective management of chronic diarrhea. Patients presenting with chronic diarrhea may exhibit a spectrum of symptoms indicative of various disorders, including IBS-D, EPI, celiac disease, SIBO, inflammatory bowel disease, and infections. These conditions often share common symptoms like diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence. To facilitate accurate diagnosis, we propose a four-step diagnostic process (Figure 2).

Step 1: Thorough History and Physical Examination

The diagnostic process begins with a comprehensive patient history and physical examination. Detailed questioning about symptom onset, duration (greater than 4 weeks defining chronic diarrhea), and characteristics of diarrhea is essential. While the clinical definition of diarrhea often revolves around increased stool frequency and loose consistency, patient perceptions can vary, emphasizing the need for detailed history taking. Patients may describe diarrhea as loose stools, increased frequency, or fecal urgency. Conversely, patients with functional constipation may paradoxically present with diarrhea complaints due to increased defecation frequency, necessitating further questioning to uncover underlying constipation symptoms.

Initial assessment should categorize diarrhea based on stool characteristics: watery (suggestive of IBS, celiac disease, endocrine disorders, or laxative abuse), fatty/greasy (suggestive of malabsorption or maldigestion, like celiac disease or EPI), or inflammatory (suggestive of infectious or inflammatory bowel disease). However, symptom overlap can blur these categories. Further history should explore diarrhea patterns (continuous, intermittent, meal-related), onset triggers, stool volume, presence of blood, mucus, or fat, nocturnal symptoms, and fecal urgency or incontinence. Associated gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms, aggravating factors (diet, stress, medications), and alleviating factors should also be investigated.

Step 2: Identify Risk Factors, Iatrogenic Factors, and Previous Diagnoses

Ruling out extrinsic factors contributing to chronic diarrhea is crucial. Inquire about recent travel history (to regions with specific diarrhea-related pathogens like Giardia), prior gastrointestinal surgeries (gallbladder removal, ileocecal resection, gastric bypass), radiation therapy, and current medications that may induce diarrhea. Pre-existing mucosal, hepatic, pancreaticobiliary, neoplastic, or systemic diseases (endocrine, vascular, immunologic) can also increase diarrhea risk and should be identified.

Step 3: Rule Out Alarm Features

Identifying alarm features is paramount to exclude more serious underlying conditions. These ‘red flags’ include recent symptom onset, especially in older individuals, nocturnal diarrhea, severe or worsening symptoms, unexplained weight loss, family history of gastrointestinal or systemic diseases (celiac disease, IBD, colorectal cancer), rectal bleeding, and unexplained iron deficiency. Presence of any alarm feature necessitates prompt further investigation.

Step 4: Initial Laboratory Workup

The patient’s history and physical examination findings guide subsequent laboratory investigations. In the presence of alarm symptoms, testing should target the most likely etiologies. For example, in patients with meal-related fatty diarrhea, weight loss, and fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, an EPI workup is warranted, with FE-1 testing being the most common initial step. However, in patients presenting with symptoms consistent with functional diarrhea or IBS-D without alarm features, current guidelines recommend screening for celiac disease (anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA and total IgA), inflammatory bowel disease (fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin and C-reactive protein), and Giardia in at-risk populations. Bile acid diarrhea testing may also be considered.

Diagnostic Algorithm for Chronic Diarrhea: Focus on IBS-D and EPI

Building upon the four-step diagnostic approach, we present a streamlined algorithm to assist clinicians in differentiating IBS-D and EPI from other chronic diarrhea syndromes (Figure 3). This algorithm aims to minimize unnecessary diagnostic testing and healthcare costs by promoting efficient and targeted investigations, leading to more timely and appropriate diagnoses and management. The algorithm offers a clear framework for rapid and accurate IBS-D diagnosis. It starts with three ‘rule-in’ questions aligning with Rome IV criteria for IBS: (1) Do you experience abdominal pain? (2) Does the pain improve or worsen with defecation? and/or (3) Is the pain associated with changes in stool frequency or form? Positive responses to these questions, in the absence of alarm symptoms, strongly suggest IBS-D, allowing for diagnosis with high accuracy. In such cases, minimal further diagnostic testing is typically required. However, if alarm symptoms are present or EPI is suspected, nutritional markers and FE-1 testing are indicated. Abnormal results necessitate further pancreatic investigation. If pancreatic evaluation is normal, a false-positive FE-1 result is likely, EPI can be excluded, and alternative causes of chronic diarrhea should be explored.

Conclusion

Chronic diarrhea presents a diagnostic challenge due to its diverse etiologies and overlapping symptom profiles. Distinguishing between conditions like IBS-D and EPI is crucial for appropriate management. The proposed diagnostic algorithm, incorporating a positive diagnostic strategy for IBS-D and targeted EPI evaluation, offers a practical approach to improve diagnostic accuracy and efficiency. By emphasizing a structured diagnostic process and minimizing unnecessary investigations, this algorithm aims to reduce diagnostic delays, improve patient outcomes, and optimize healthcare resource utilization in the management of chronic diarrhea. Accurate and timely differential diagnosis is paramount in alleviating patient suffering and reducing the broader societal burden of chronic diarrhea.