I. Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia: Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) represents a diverse group of acquired disorders characterized by the premature destruction of red blood cells (RBCs) due to autoantibodies. This destruction is orchestrated by a complex interplay of autoantibodies, complement activation, macrophages, T-lymphocytes, and cytokines. The aging immune system, marked by immunosenescence, is increasingly recognized as a significant factor in the development of autoimmunity, including AIHA [1]. A cornerstone of AIHA diagnosis is the positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT), which confirms the presence of immunoglobulins (predominantly IgG, but also IgM, IgA, and/or complement, typically C3d) attached to RBCs [2].

AIHA is clinically categorized into several serological types: warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (wAIHA), cold agglutinin disease (CAD), mixed-type AIHA, and paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria (PCH). Recently, an atypical, DAT-negative AIHA form, characterized by IgA and warm IgM, has been identified [2]. Primary CAD is now defined by the presence of a low-grade lymphoproliferative disorder (LPD) or unclassified B-cell lymphoproliferation in the bone marrow [3]. In contrast, cold agglutinin syndrome (CAS) describes the presence of cold agglutinins secondary to other underlying conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, Epstein-Barr virus infection, or aggressive lymphoma [4]. AIHA can be classified as primary (idiopathic) when no underlying cause is identified, or secondary, associated with autoimmune diseases, lymphoproliferative disorders, infections (including SARS-CoV-2), solid tumors, or organ transplantation (Table 1) [3, 5, 12, 13]. Notably, AIHA is also observed with increasing frequency in patients post-allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), often presenting with a severe course and high mortality [14–17]. Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia (DIIHA), triggered by medications, is now considered a secondary form of AIHA [3].

Table 1. Common Secondary Conditions Associated with Different AIHA Types [5–7]

| Type of AIHA | Etiology |

|---|---|

| Warm AIHA | Hematologic disorders and lymphoproliferative diseases (CLL, Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) |

| Solid malignancy (thymoma, ovarian or prostate carcinoma) | |

| Autoimmune diseases (SLE, Sjögren syndrome, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, colitis ulcerosa, PBC) | |

| Viral infections (HCV, HIV, VZV, CMV, SARS-CoV-2) | |

| Bacterial infections (tuberculosis, pneumococcal infections) | |

| Leishmania parasites | |

| Bone marrow or solid-organ transplantation | |

| Primary immune deficiency syndromes (CVID, ALPS) | |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| CAD | Lymphoproliferative diseases (Waldenström macroglobulinemia, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) |

| Solid malignancy | |

| Infections (parvovirus B19, Mycoplasma sp., EBV, adenovirus, influenza virus, VZV infections and syphilis) | |

| Autoimmune disease | |

| Post-allogeneic HSCT | |

| PCH | Bacterial infections (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli infections and syphilis) |

| Viral infections (adenovirus, influenza A virus, VZV infection; mumps, measles) | |

| Myeloproliferative disorders | |

| Mixed AIHA | Lymphoma |

| SLE | |

| Infection | |

| DIIHA | Antibiotics (cephalosporins, beta-lactamase inhibitors, cotrimoxazole) |

| Antiviral drugs: HAART | |

| Anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) | |

| Chemotherapy (carboplatin, oxaliplatin) | |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (diclofenac) | |

| Others: methyldopa |

AIHA autoimmune hemolytic anemia, ALPS autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, anti-PD-1 anti programmed death-1, CAD cold agglutinin disease, CLL chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, CMV cytomegalovirus, CVID common variable immunodeficiency, DIIHA drug-induced immune hemolytic anaemia, EBV epstein-barr virus, HAART highly active antiretroviral therapy, HCV hepatitis C, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, HSCT haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, PBC primary biliary cirrhosis, PCH paroxysmal cold haemoglobinuria, SLE systematic lupus erytremathosus, VZV varicella zoster virus

Recent advancements in understanding AIHA pathogenesis and treatment necessitate a comprehensive review of current knowledge. This article aims to summarize the latest insights into this complex and still incompletely understood disease, particularly emphasizing the diagnostic challenges and how disease characteristics may vary with age-related immunological changes in older adults with AIHA.

II. Epidemiology and Risk Factors: The Rising Incidence with Age

The estimated incidence of AIHA is 1.77 cases per 100,000 individuals annually [18], with wAIHA being the most prevalent form, accounting for approximately two-thirds of cases [19]. CAD is the second most common type, representing 15–20% of AIHA cases [20]. CAD typically manifests in individuals over 50 years old, with the highest incidence in the seventh and eighth decades of life [21, 22]. PCH, conversely, is a rare condition primarily affecting children [23], with adult cases being extremely uncommon and often linked to infections [24]. The risk of AIHA, especially wAIHA, escalates with age, showing a fivefold increase in the seventh decade compared to the fourth [21]. This age-related susceptibility is potentially attributed to immunosenescence [25] or the accumulation of epigenetic abnormalities in hematopoietic cells during aging [26]. Aging and associated comorbidities also elevate the likelihood and severity of oxidative stress and eryptosis, processes leading to RBC senescence and premature destruction [27, 28]. Genetic predisposition, immunodeficiency, autoimmune disorders, infections, medications (particularly novel anti-cancer drugs), malignancies (especially CLL/NHL), and transplants are recognized as significant risk factors for AIHA development [29]. The clinical spectrum of AIHA ranges from mild to severe, life-threatening forms, with a course that can be chronic, recurrent, or rarely episodic. The estimated mortality rate for AIHA is approximately 10% [17, 30–32].

III. Unraveling the Pathogenesis: A Multifaceted Autoimmune Response

AIHA pathogenesis is believed to arise from the interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers. The immune system’s components, including autoantibodies, cytokines, complement system, phagocytes, B and T lymphocytes (cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and CD4+ regulatory T cells (Tregs)), and NK cells, are all implicated in AIHA development and are subject to age-related changes. Similar to other autoimmune conditions, AIHA is associated with disruptions in central and peripheral self-tolerance mechanisms, leading to the emergence of autoreactive T and B cells [33, 34]. Naturally occurring CD4+ and CD25+ Tregs play a critical role in maintaining immunological self-tolerance by suppressing autoreactive T cells. Murine AIHA models have demonstrated that impaired suppressive activity of CD4+ and CD25+ Tregs can be pivotal in inducing autoantibody production against RBCs and sustaining AIHA [35]. Conversely, other murine studies suggest that Tregs may not be essential for preventing RBC autoimmunity [36]. Reviews of animal models highlight oxidative stress as a risk factor and reticulocytes as targets for pathogenic autoantibodies [37]. One model showed increased autoantibodies on reticulocytes, elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and preferential clearance of reticulocytes [38]. These autoantibodies preferentially bound to reticulocytes and induced phosphatidylserine expression [39], potentially explaining reticulocytopenia in some AIHA cases. Further research suggests peripheral tolerance mechanisms may be more critical than thymic central tolerance [37].

T helper type 17 (Th17) cells and Treg cells, originating from a common naive CD4+ T cell precursor, have opposing roles: Th17 cells promote inflammation and autoimmunity, while Tregs suppress these processes, maintaining immune homeostasis. Studies have observed increased Th17 cell numbers in AIHA patients, correlating with disease activity [40]. Interleukin 17 (IL17) levels also closely correlate with AIHA disease activity, supporting the role of Th17 cells in AIHA development [40]. Immune dysregulation in AIHA may be linked to specific cytokine gene polymorphisms, potentially resulting in a Th17/Tregs imbalance [41–43]. Recent AIHA mouse model research highlights the involvement of T follicular helper cells (Tfh) and T follicular regulatory cells (Tfr) in B cell differentiation and anti-RBC antibody regulation [44]. Furthermore, clonal expansions of CD8+ T cells are found in AIHA, persisting during remission but not correlating with disease severity or duration, suggesting accumulation during the autoimmune process [45].

Secondary warm AIHA, accounting for about half of cases, is often linked to underlying infections. Molecular mimicry, where pathogen antigens resemble self-antigens, is a potential mechanism for pathogen involvement in AIHA induction and progression [33, 34, 46]. HIV infection, for instance, can induce autoantibody production via molecular mimicry [47] and is a significant risk factor for AIHA, increasing incidence over 20-fold [8, 48]. Loss of immunological tolerance is crucial in HIV infection and other immunodeficiencies like common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) and autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) [49–51].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are increasingly recognized in AIHA pathogenesis [34]. Increased oxidative stress in RBCs due to cytoplasmic Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) deficiency is linked to anemia and autoantibody production [52]. SOD1-deficient mice exhibit elevated RBC ROS levels, RBC component oxidation, and increased autoantibody production, with lipid peroxidation products like 4-hydroxy 2-nonenal and acrolein acting as autoantibody epitopes on RBC membranes [53]. Elevated anti-RBC autoantibodies correlate with increased RBC ROS levels [34]. Animal models show that transgenic overexpression of human SOD1 in erythroid cells prolongs lifespan and alleviates AIHA symptoms [54], while antioxidants like N-acetyl cysteine suppress autoantibody production, supporting the oxidative stress theory [34]. Plasma-free heme, a hemolysis byproduct, induces neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation via ROS signaling, impacting immune cell function regulation [55].

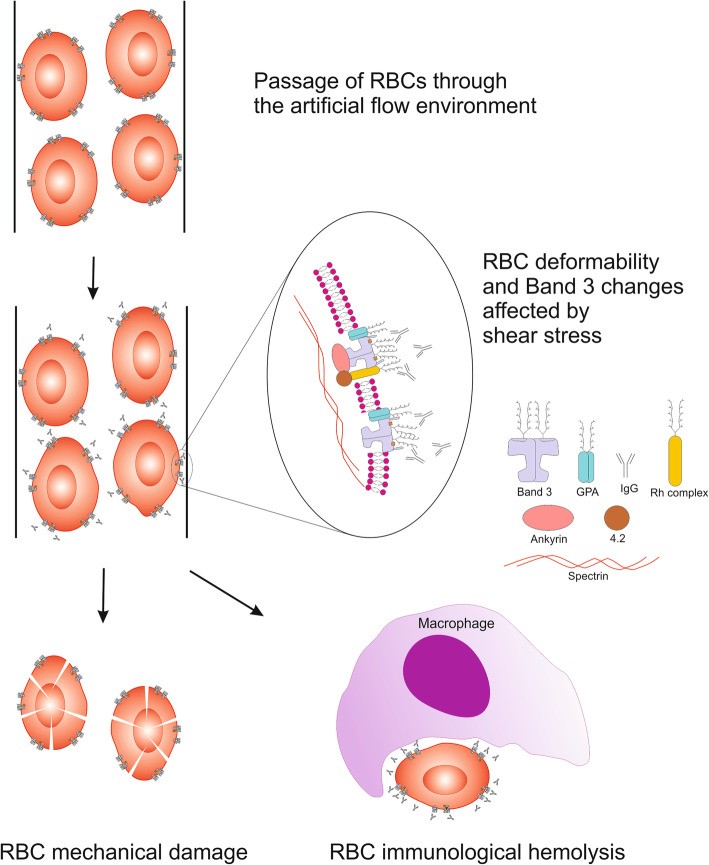

Shear stress is also implicated in autoimmune response induction, AIHA progression, and accelerated RBC senescence [56]. Increased IgG binding to RBC membranes under high shear stress indicates conformational changes in RBC membrane proteins, possibly exposing epitopes to naturally occurring antibodies (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Schematic Visualization of RBCs Exposed to Shear Stress

Alt Text: Diagram illustrating red blood cells under shear stress, highlighting membrane deformation and potential epitope exposure.

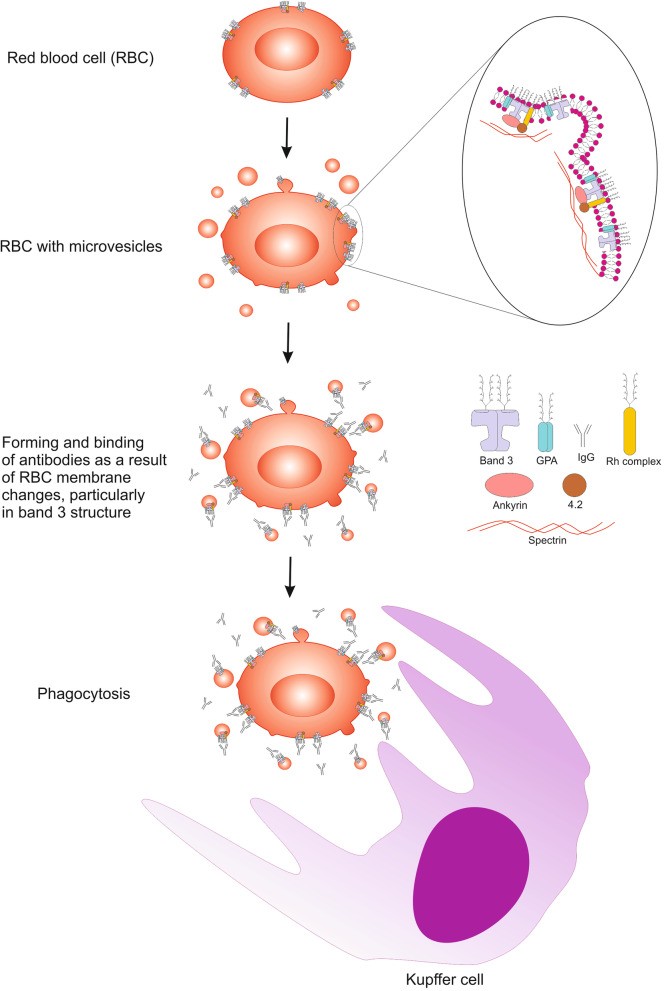

Microvesicles released from stored RBCs contain lipid raft proteins and oxidized signaling components associated with RBC senescence. Vesiculation contributes to irreversible membrane changes and immune response activation [57, 58] (Fig. 2). Erythrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) from stored RBC units possess immunomodulatory properties, affecting B lymphocyte vitality, plasma cell differentiation, and antibody production [59], potentially influencing AIHA course in transfusion recipients.

Fig. 2. Schematic Visualization of Erythrocyte Senescence and Microvesicle Generation

Alt Text: Illustration depicting the process of red blood cell senescence, showing membrane changes and the release of microvesicles.

Genetic factors also play a significant role in AIHA. Trisomy 3 was identified as a consistent chromosomal change in CAD preceding lymphoproliferative malignancies [60]. Next-generation sequencing revealed recurrent KMT2D and CARD11 gene mutations in CAD patients [61]. Cytogenetic microarrays and exome sequencing identified recurrent increases in chromosomes 3, 12, or 18 in CAD-associated lymphoproliferative disease [62], resembling genetic features of nodal and extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) [63]. Genetic predisposition and immune dysregulation are also implicated in autoimmune phenomena in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients. Almost all CAD patients exhibit monoclonal antibodies encoded by the IGHV4–34 gene, responsible for I antigen binding [64–66]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are also implicated in gene expression disturbances in CLL and are involved in both CLL and autoimmune cytopenia pathogenesis [64, 67, 68]. AIHA secondary to CLL is associated with immune response regulatory abnormalities, including miRNA downregulation [69], autoreactive polyclonal B cells (mainly IgG) and neoplastic monoclonal B lymphocytes (mainly IgM) [64], induction of autoreactive Th cells via B cell activator (BAFF) and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), nonfunctional Treg formation [70], and altered Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression (reduced TLR4, lower TLR2, increased TLR7, TLR9, and TLR10) [71].

IV. Diagnostic Challenges and Serological Characteristics of AIHA Subtypes

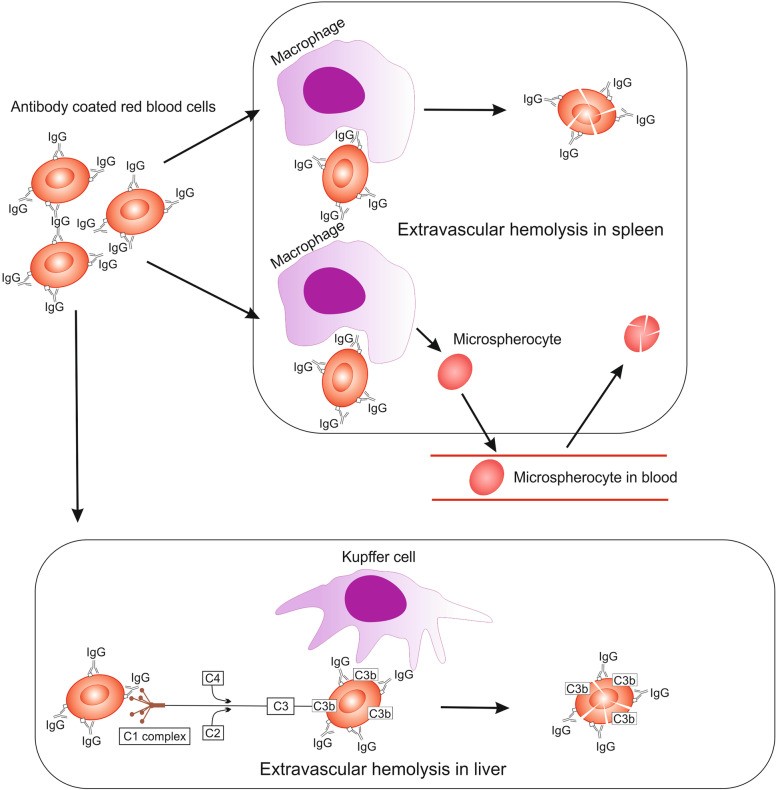

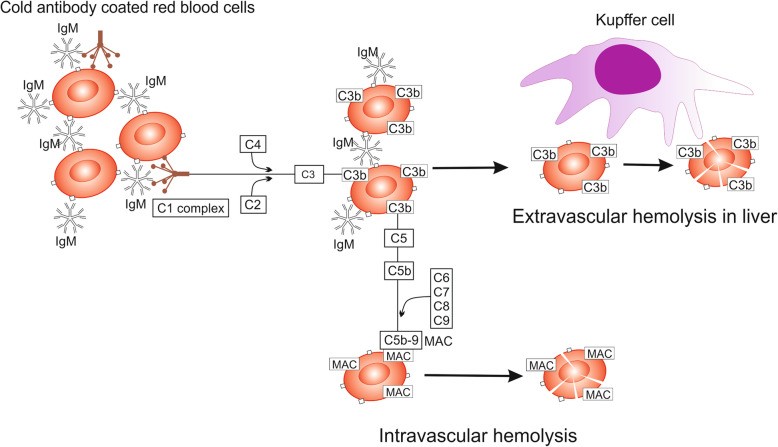

The clinical presentation and underlying pathological mechanisms of AIHA vary depending on the specific subtype. In wAIHA, hemolysis can range from subtle to severe, potentially causing significant tissue hypoxia. Jaundice is a common sign of extensive hemolysis. Mild to moderate splenomegaly is often observed in active hemolysis, while disproportionate or nodular splenomegaly suggests secondary forms, particularly in lymphoproliferative disorders [9, 10, 32]. In wAIHA, IgG autoantibodies and/or complement destroy RBCs at approximately 37°C, mainly through extravascular hemolysis in the spleen. IgG antibodies can also weakly activate complement, depositing C3 fragments on RBCs, leading to Kupffer cell destruction in the liver (Fig. 3). Terminal complement pathway activation can result in membrane attack complex (MAC) formation on RBCs and intravascular hemolysis [9, 73]. Diagnostic testing in wAIHA typically reveals a DAT positive for IgG alone or IgG ± C3d, with negative cold agglutinins (Table 2).

Fig. 3. Hemolysis in Warm AIHA: Pathological Mechanisms and Sites of Hemolysis

Alt Text: Diagram illustrating the process of hemolysis in warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia, showing antibody-coated red blood cells being destroyed in the spleen and liver.

Table 2. Serologic Characteristics of Different AIHA Types [3, 11, 74]

| Type of AIHA | Antibody type | Typical DAT | RBC eluate | Antigen specificity | Antibody titre at 4 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warm AIHA | IgG (rarely IgA or IgM) | IgG or IgG + C3 | IgG | panreactive | – |

| CAD | IgM | C3 | nonreactive | usually anti-Ia | usually > 1:500 |

| PCH | biphasic IgG | C3 | nonreactive | usually anti-P | |

| Mixed AIHA | IgG, IgM | IgG + C3 | IgG | usually lack specificity of warm IgG, cold antibody differentlyb | cold antibodies |

| DIIHA | Ig G | IgG or IgG + C3 | IgG | often Rh-related | – |

asometimes anti-i, rarely anti-Pr

banti I, anti-i or lack specificity

In CAD, symptoms are often triggered by temperature fluctuations, with rapid cooling exacerbating hemolysis. Anemia-related symptoms are dominant, and cold exposure can induce acrocyanosis (bruising and/or redness of distal body parts). Prolonged cold exposure can lead to ischemia and necrosis [74]. Cooling distal body parts activates IgM autoantibodies to bind to erythrocyte membranes, causing RBC agglutination (Fig. 4). The antigen-IgM complex activates the classical complement pathway, forming C3b. Upon rewarming to 37°C, IgM antibodies detach, but C3b remains on the RBC membrane. Enzymatic conversion of C3b yields C3d, detected in DAT [75, 76].

Fig. 4. Hemolysis in Cold Agglutinin Disease (CAD)

Alt Text: Diagram illustrating the mechanism of hemolysis in cold agglutinin disease, highlighting IgM antibody binding in cold temperatures and complement activation.

Mixed AIHA, accounting for less than 10% of cases, typically presents with a chronic course, not directly linked to cold temperatures. Antibody activation occurs across a broader temperature range (>30°C) [73, 77].

PCH should be considered in patients under 18 with hemolysis associated with cold exposure and infections. PCH symptoms include back or leg pain, abdominal cramping, fever, chills, jaundice, and dark urine, particularly at urination onset [78, 79]. Primarily intravascular hemolysis in PCH may not always manifest with severe clinical symptoms. PCH is caused by polyclonal IgG antibodies binding RBCs in cold temperatures (below normal body temperature), fixing complement and causing complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis upon rewarming. The thermal amplitude is typically around 20°C [73, 77].

V. Diagnostic Approaches and the Crucial Role of Laboratory Testing

AIHA diagnosis, like other hemolytic anemias, often reveals normocytic anemia with spherocytes on peripheral blood smears. Reticulocytosis, although reticulocytopenia can occur, is a common but non-specific finding, indicating compensatory erythropoiesis in response to hemolysis. The bone marrow responsiveness index (BMRI), calculated using absolute reticulocyte count and hemoglobin levels, has been proposed for assessing erythropoiesis insufficiency [80]. Elevated indirect bilirubin, low or absent serum haptoglobin, increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and elevated urinary urobilinogen are hallmarks of hemolysis. Hemoglobinuria, an early symptom, indicates intravascular hemolysis, followed by hemosiderinuria after about a week [80]. The DAT confirms the immune-mediated mechanism. However, low autoantibody titers or inadequate antibody testing can lead to false-negative DAT results in 5–10% of AIHA cases, even with highly sensitive tests [2].

The DAT uses monospecific anti-globulins to detect autoantibodies against immunoglobulins (IgG1 or IgG3) and complement fragments (C3d and C3c) on RBC surfaces. Kits contain anti-IgG, anti-IgA, anti-IgM, anti-C3d, and anti-C3c monospecific antibodies. In contrast to DAT, the indirect antiglobulin test (IAT; indirect Coombs test) detects free anti-RBC antibodies in patient serum. Free IgM antibodies are examined in low ionic strength solution (LISS) or via cold washing to enhance detection of low-affinity autoantibodies. Eluate preparation, detaching antibodies from RBCs and assessing their reactivity with donor erythrocytes, confirms autoantibody presence. Cold agglutinin titer is diagnostic for CAD. Autoantibodies are monoclonal in CAD and lymphoma-associated CAS but polyclonal in infection-related CAS [74]. CAD monoclonal IgM often shows kappa light chain predominance (κ), with occasional lambda light chains (λ) [22, 74]. For patients under 18 with atypical serology, hemoglobinuria, or cold-induced symptoms, a Donath-Landsteiner test is performed [9, 73, 77]. Differential diagnosis should consider secondary AIHA causes, underlying conditions, and medications. Due to the significantly increased venous thromboembolism risk in AIHA [81], prompt diagnosis is crucial. Bone marrow examination is recommended for CAD patients over 60, those with suggestive clinical presentations (weight loss, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly), or peripheral blood abnormalities (lymphocytosis, cytopenias) to rule out CAD-associated lymphoproliferative disorders [73]. Bone marrow evaluation is also advised in relapsed/refractory wAIHA and at CAD diagnosis [29]. Bone marrow studies in primary AIHA have revealed intraparenchymatous nodules with monoclonal B cells in CAD patients, distinct from known B-cell lymphomas [82]. Bone marrow fibrosis (BMF) was found in over a third of AIHA patients, with increased cellularity and dyserythropoiesis in at least two-thirds, correlating with the need for later-line treatments [83]. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) clones were found in a third of primary AIHA patients, associated with higher LDH and hemolytic patterns [84].

VI. Current Treatment Modalities and Future Therapeutic Directions

AIHA treatment necessitates individualized approaches, with frequent clinical re-evaluation and therapy adjustments. Elderly patients, with lower anemia tolerance, often require treatment and are more susceptible to adverse drug reactions and drug interactions. Treatment strategies depend on AIHA subtype, symptom severity, underlying causes, and comorbidities. Symptomatic anemia is the primary indication for therapy in both newly diagnosed and persistent AIHA. Secondary AIHA management emphasizes treating underlying autoimmune diseases.

For all symptomatic AIHA cases, folic acid and other necessary vitamin supplements are essential. RBC transfusions are reserved for critical cases with severe anemia (hemoglobin <7 g/dL) and life-threatening situations [3]. First-line treatment for wAIHA is typically glucocorticosteroids (GKS), such as prednisone at 1 mg/kg orally or intravenous methylprednisolone [3]. Approximately 80% of patients respond within 2–3 weeks [88, 89], but long-term remissions after GKS withdrawal are achieved in only 20–30% of cases [30, 32]. If no improvement occurs after 3 weeks of GKS, other medications are usually added. Combination therapy of rituximab (RTX) with GKS as first-line treatment may yield better responses than GKS monotherapy [90, 91]. Meta-analysis suggests RTX treatment is more effective than RTX-free regimens for AIHA and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia [92]. RTX reduces the need for repeated GKS treatment, particularly beneficial for older patients with comorbidities, who are at higher risk of GKS-related adverse effects like gastrointestinal bleeding, osteoporosis, and diabetes. Osteoporosis prevention is recommended for all patients over 50, and proton pump inhibitors for patients over 60 or those using NSAIDs, anticoagulants, or antiplatelet agents [77]. RTX is a second-line treatment option for AIHA, with a 70–80% response rate [91, 93, 94], typically administered at 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks. Low-dose RTX (100 mg weekly for 4 weeks) has shown efficacy in primary AIHA, particularly wAIHA, but with significant relapse rates within 2 years [95]. RTX efficacy and safety are demonstrated in older patients [96], with a study in elderly refractory wAIHA patients (median age 78 years) showing an 86.9% response rate and median overall survival of 87 months [96], though relapses within 2 years are common. A rare RTX complication is progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy due to JV virus reactivation [9]. Splenectomy may be considered as a third-line option for wAIHA [3], achieving response in 40–90% of primary wAIHA patients, but with approximately 80% relapse rates [32, 80, 97, 98]. Splenectomy is invasive, irreversible, and carries increased risks of thrombosis and encapsulated bacterial infections. While complication and mortality risks have decreased, data on efficacy and safety in elderly wAIHA patients are lacking [99]. Immunosuppressive drugs, azathioprine and mycophenolate-mofetil, are alternatives to RTX in SLE-associated wAIHA [3]. Cyclophosphamide or autologous bone marrow transplantation have weaker evidence and higher complication risks [3]. Combination therapies, such as CTX plus rituximab plus dexamethasone, show improved response rates in immune cytopenias in CLL [100]. CLL-associated AIHA management depends on CLL stage. Early-stage CLL-associated AIHA is treated similarly to primary AIHA. Patients with CLL requiring therapy (Rai stage III/IV or Binet stage C) or unresponsive to GKS and RTX need CLL-targeted therapy [3].

CAD treatment is not recommended for mild cases (Hb > 10 g/dL). Patients with comorbidities like ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, or COPD, and hypoxia symptoms may require treatment at higher Hb levels [3]. Thermal protection of distal body parts is advised for CAD patients. Rituximab, alone or in combination, especially with bendamustine, is first-line treatment for severe CAD [3, 74]. RTX monotherapy achieves 45-54% overall response rates, but remissions are not durable [86, 101], with a median response duration of 11 months reported [22]. Meta-analysis shows a 57% ORR for RTX in CAD, with only a 21% complete response rate (CRR) [94]. RTX combined with bendamustine yields a 71% response rate, including 40% CRR with acceptable toxicity in fit patients [102]. RTX-fludarabine immunochemotherapy achieved a 76% response rate (21% CRR) with a median remission of 66 months [103]. Eculizumab, a C5 complement inhibitor, is another option. A phase 2 trial showed reduced hemolysis and transfusion needs in CAD patients treated with eculizumab [104]. High eculizumab efficacy in fulminant hemolytic anemia in primary CAD has been reported [105], as well as effective hemolysis inhibition in severe, idiopathic wAIHA unresponsive to GKS, intravenous immunoglobulin, mycophenolate mofetil, and RTX [106]. Plasmapheresis is considered for severe hemolysis, effectively removing cold agglutinins, but only transiently. Albumin replacement fluid is crucial to avoid complement activation from plasma infusion [107]. Splenectomy is not recommended for CAD due to the liver’s primary role in extravascular hemolysis. RBC transfusions using warmed blood may be necessary in severe symptomatic anemia [74].

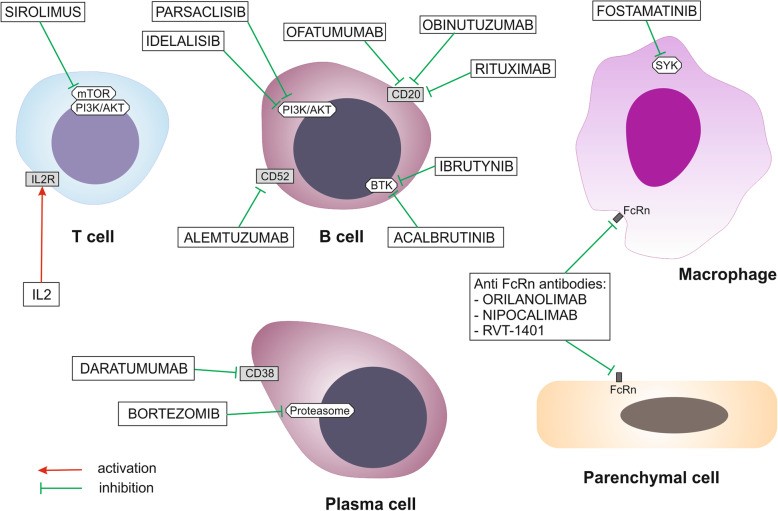

Future AIHA therapy prospects are focused on novel agents targeting B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, complement cascade, spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) on macrophages, and the neonatal crystallizable fragment receptor (FcRn) (Fig. 5). New drug classes are in clinical trials (Table 3).

Fig. 5. New Potential Drugs Targeting Immune Cells in AIHA Therapy

Alt Text: Diagram illustrating new drug targets for autoimmune hemolytic anemia therapy, focusing on immune cells like B cells, T cells, and macrophages.

Table 3. Ongoing Clinical Trials of New Drug Groups in AIHA

| Intervention/ treatment | Group of agents | Condition or disease | Phase of study | ClinicalTrials.gov |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sirolimus plus ATRA | mTOR inhibitor plus tretinoin | refractory AIHA | 2 and 3 | NCT04324411 |

| Idelalisib vs. ibrutinib | PI3Kδ inhibitor vs. BTK inhibitor | autoimmune cytopenia in the course of CLL | retrospective | NCT03469895 |

| Parsaclisib | PI3Kδ inhibitor | AIHA | 2 | NCT03538041 |

| Ibrutinib | BTK inhibitor | steroid refractory warm AIHA | 2 | NCT03827603 |

| refractory/relapsed AIHA | 2 | NCT04398459 | ||

| Ibrutinib or idelalisib | BTK inhibitor | AIHA associated with CLL | retrospective | NCT03469895 |

| Interleukine-2 | cytokine | resistant, warm AIHA | 1 and 2 | NCT02389231 |

| Low dose rituximab plus alemtuzumab | anti CD20 antibody plus anti CD52 antibody | refractory autoimmune cytopenias | 2 and 3 | NCT00749112 |

| Fostamatinib | SYK inhibitor | warm AIHA | 3 | NCT03764618 |

| 2 | NCT02612558 | |||

| SYNT001 (ALXN1830) | anti-FcRn antibody | warm AIHA | 1 and 2 | NCT03075878 |

| SYNT001 (ALXN1830) vs. placebo | 2 | NCT04256148 | ||

| M281 | 2 and 3 | NCT04119050 | ||

| RVT-1401 | 2 | NCT04253236 | ||

| Levamisole plus prednisolone | immunomodulatory drug plus GKS | warm AIHA | 2 | NCT01579110 |

| BIVV009 (Sutimlimab) | complement C1 inhibitor | CAD | 3 | NCT03347422 |

| 3 | NCT03347396 | |||

| APL2 | complement C3 inhibitor | warm AIHA, CAD | 2 | NCT03226678 |

AIHA autoimmune hemolytic anemia, ATRA all trans-retinoic acid, BTK Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, CLL chronic lymphocytic leukemia, FcRn neonatal crystallizable fragment of the receptor, mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin kinase, PI3K phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, SYK spleen tyrosine kinase

Lymphocyte-modulating treatments targeting the interleukin 2 receptor (IL2R), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and mTOR axis are promising. Sirolimus and IL2 disrupt pathological T lymphocyte function. Idelalisib and PI3K δ inhibitors target the PI3K axis, affecting pathological B lymphocyte dysregulation. Sirolimus has shown efficacy in post-transplant AIHA in children [109] and resistant AIHA [110]. Plasma cells are targeted by proteasome inhibitors and anti-CD38 antibodies. Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, showed positive responses in refractory wAIHA patients [111, 112]. Daratumumab (anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody) demonstrated rapid and sustained responses in refractory AIHA post-HSCT in children [113] and adults [114]. Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors and anti-CD20 or CD52 antibodies induce proliferation disorder and apoptosis of pathological B lymphocytes. Acalabrutinib, a BTK inhibitor for relapsed/refractory CLL, may reduce concomitant autoimmune cytopenia, including AIHA [115]. New anti-CD20 antibodies like ofatumumab are being developed [116]. Alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) and RTX combination induced short-term responses in primary AIHA patients [117].

Macrophages are targeted by SYK inhibitors, with fostamatinib being the first in class. Fostamatinib impairs macrophage function and blocks phagocytosis of antibody-coated RBCs. Orilanolimab (SYNT001), a humanized monoclonal antibody, blocks the interaction between FcRn and IgG, preventing IgG salvage from lysosomal degradation, promoting IgG degradation, and reducing total serum IgG concentrations [118]. Other anti-FcRn monoclonal antibodies, M281 (nipocalimab) and RVT-1401, are under development to reduce IgG levels.

Complement modulation in AIHA therapy is possible at C1 complex, C3, and C5 convertase levels (Table 4).

Table 4. Complement Modulation in AIHA Treatment: Current and Future Agents

| Level of complement pathway modulation | Novel agents | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| C1 complex (C1q, C1r, C1s) | ANX005 | anti-C1q monoclonal antibody |

| TNT003 | anti-C1s monoclonal antibody | |

| PIC1 | peptide inhibitor | |

| Sutimlimab | anti-C1s monoclonal antibody | |

| C3 complement | Compstatin Cp40 | long-acting form polyethylene glycol |

| Pegcetacoplan (APL2) | pegylated compstatin analog | |

| C5 complement | Eculizumab | anti-C5 monoclonal antibody |

Peptide C1 complement inhibitors (PIC1) block the classical and lectin complement pathways [119]. TNT003, a murine anti-C1s monoclonal antibody, has shown in vitro and in vivo effectiveness [120, 121]. Sutimlimab, a humanized anti-C1 monoclonal antibody (BIVV009 or TNT009), rapidly inhibits hemolysis in CAD patients, increases Hb, resolves anemia, and maintains transfusion independence [122, 123]. ANX005 (humanized anti-C1q antibody) clinical trial results in CAD are pending, with in vitro studies using mouse erythrocytes and human CAD serum showing promise [124]. Compstatin Cp40 inhibits C3b opsonization of erythrocytes, with in vitro and preclinical studies demonstrating effects [125–127]. Eculizumab, a C5 blocker, is used in persistent, severe AIHA [104–106]. In silico and in vitro research seeks new compounds inhibiting initial complement pathways, with 1,2,4-triazole showing potential [128].

VII. Conclusion: Bridging the Knowledge Gap and Future Directions in AIHA

AIHA remains a complex and heterogeneous group of diseases where, despite significant advances in understanding pathogenesis and treatment, knowledge gaps persist. Its intricate diagnostics and management require personalized approaches. Refractory or recurrent cases necessitate sequential treatment strategies. AIHA continues to pose therapeutic challenges, underscoring the importance of ongoing research into novel therapies. Intensive research into new drugs targeting B cells, plasma cells, T cells, and macrophages is underway. Increased understanding of complement’s role in autohemolysis has driven the development of complement pathway inhibitors at various levels. Establishing national AIHA registries would facilitate data collection, monitoring, and disease awareness. Consistent terminology, standardized diagnostic and classification criteria, and uniform response criteria are crucial for data collection efforts. Studies comparing different therapies’ impact on quality of life and transfusion needs are warranted. Further clinical and basic research into treatment options, particularly addressing the specific characteristics of older patients, is essential to advance AIHA management and bridge the existing knowledge deficit.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

AIHA Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

ALPS Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome

ADCC Antibody dependent cell cytotoxicity

APL2 Complement C3 inhibitor

ATRA All trans-retinoic acid

BIVV009 Complement C1s inhibitor

BTK Bruton’s tyrosine kinase

CAD Cold agglutinin disease

CD Cluster of differentiation – cell surface antigen

CAS Cold agglutinin syndrome

CLL Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

CVID Common variable immunodeficiency

CRR Complete response rate

Compstatin Cp40 Complement C3 inhibitor

DAT Direct antiglobulin test

DIIHA Drug-induced immune hemolytic anaemia

FcRn Neonatal crystallizable fragment of the receptor

GKS Glucocorticosteroid

HAART Highly active antiretroviral therapy

HIV Human immunodeficiency virus

HSCT Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

IL2 Interleukin 2

IL2R Interleukin 2 receptor

ICIs Immune checkpoint inhibitors

MAC Membrane attack complex

mTOR Mammalian target of rapamycin kinase

NHL Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

OSR Overall survival rate

PCH Paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria

PBC Primary biliary cirrhosis

PIC1 Peptide inhibitor of complement C1

PI3K Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

PI3K/AKT Intracellular signaling pathway

RBCs Red blood cells

RTX Rituximab

SLE Systemic lupus erythematosus

SYK Spleen tyrosine kinase

SYNT001 Monoclonal antibody

TNT003 Anti-C1s antibody

Tfh T follicular helper cells

Tfr T follicular regulatory cells

Tregs Regulatory T cells

VTE Venous Thromboembolism

wAIHA Warm AIHA

HBV Hepatitis B virus

Authors’ contributions

SSM has made the conception, design of the work and prepared all Figures. SSM, AO-G, JR-M, EW-R, LG wrote the draft of the manuscript. EN reviewed the manuscript. LG provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

1. Danese, S., & Rossi, P. (2018). Immunosenescence and Autoimmunity. International journal of molecular sciences, 19(8), 2385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19082385

2. Brodsky, R. A. (2019). Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America, 33(2), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2018.11.001

3. Jäger, U., Barcellini, W., Broome, C. M., Gertz, M. A., Hill, A., Hillmen, P., … & Berentsen, S. (2019). Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults: recommendations from the First International Consensus Meeting. Blood reviews, 34, 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2019.04.003

4. Berentsen, S., & Tjønnfjord, G. E. (2012). Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune hemolytic anemias. Hematology, 2012(1), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.195

5. Gertz, M. A. (2017). Cold agglutinin disease. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America, 31(2), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2016.10.005

6. De Silva, D. L., & Jonsson, A. H. (2018). Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults-current insights. Blood research, 53(4), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.22020/br.2018.0092

7. Packman, C. H. (2020). Drug-induced hemolytic anemia. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program, 2020(1), 630–637. https://doi.org/10.1182/hematology.2020000169

8. रेगे, एस., Naicker, S., & Perkovic, V. (2016). HIV-associated autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine, 95(22), e3733. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003733

9. Barcellini, W. (2017). New insights in autoimmune hemolytic anemia: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Hematology, 2017(1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.70

10. Hill, Q. A., Stamps, R., & Massey, E. (2017). Guidelines for the management of warm autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. British journal of haematology, 176(3), 395–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14474

11. Swanson, K. J., & McFarland, J. G. (2019). Immune Hemolytic Anemia. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 94(8), 1709–1721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.031

12. Lazarian, G., Quinquenel, A., Bellal, M., Salliot, C., Beaumont, M., Vignon, M., … & Michel, M. (2020). Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in COVID-19 infection. British journal of haematology, 190(1), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16794

13. Ronzoni, V., Barilaro, A., Scolfaro, C., Fogazzi, P., Quaglia, F., & Salvaneschi, L. (2020). Autoimmune hemolytic anemia as first manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a child. Transfusion and apheresis science : official journal of the World Apheresis Association : official journal of the European Society for Haemapheresis, 59(5), 102941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transci.2020.102941

14. Choi, J. H., Kim, S. J., Kim, K., Lee, J. H., Choi, S. J., Lee, J. Y., … & Kim, W. S. (2011). Autoimmune hemolytic anemia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: clinical characteristics, treatment, and prognosis. Bone marrow transplantation, 46(7), 983–989. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2010.271

15. Sanz, J., Arriaga, F., Montesinos, P., Lorenzo, I., Pinana, J. L., Perez-Simon, J. A., … & Sanz, G. F. (2010). Autoimmune hemolytic anemia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: clinical characteristics and risk factors. Bone marrow transplantation, 45(1), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2009.136

16. Tichelli, A., Gratwohl, A., Wursch, A., Nissen, C., & Speck, B. (1992). Autoimmune hemolytic anemia after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood, 80(4), 878–882.

17. Zecca, M., Nobili, B., Luciani, M., Angelini, P., Bondanini, F., Bossi, G., … & Barcellini, W. (2019). Autoimmune cytopenias after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Haematologica, 104(4), 867–875. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2018.201618

18. Michel, M. (2018). Classifying autoimmune hemolytic anemias: beyond warm and cold. Hematology, 2018(1), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.191

19. Sokol, R. J., Hewitt, S., & Stamps, R. (2004). Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia: diagnosis and management. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 328(7435), 247–251. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7435.247

20. Berentsen, S. (2018). Cold agglutinin disease. Hematology, 2018(1), 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.226

21. Andersson, M. L., Hässler, S., & Wadström, J. (2017). Incidence of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults: a population-based cohort study from southern Sweden. Haematologica, 102(3), e91–e94. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2016.157950

22. Berentsen, S., Randen, U., & Vågan, A. M. (2017). Cold agglutinin disease: an update. Hematology, 2017(1), 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.226

23. Sokol, R. J., Booker, D. J., Stamps, R., & স্ট্যাম্পস, আর. (2002). Paroxysmal cold haemoglobinuria in childhood. Journal of clinical pathology, 55(3), 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.55.3.180

24. Garratty, G. (2009). Paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria. Immunohematology, 25(2), 67–73.

25. Globig, A. M., Hässler, S., & Andersohn, F. (2018). Risk factors for autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a case-control study. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety, 27(8), 899–906. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4582

26. Busque, L., & Gale, R. E. (2017). Somatic mutations in normal hematopoiesis and implications in clonal hematopoiesis and AML. Leukemia, 31(4), 789–797. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2016.364

27. Bartosz, G. (2005). Reactive oxygen species: properties, detection, and roles in animal cells. Free radical biology & medicine, 38(4), 480–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.028

28. Foller, P., Lang, F., & Lang, E. (2008). Oxidative stress and suicidal erythrocyte death. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology, 457(2), 667–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-008-0539-4

29. Barcellini, W., Fattizzo, B., Zaja, F., Marchetti, M., Zaninoni, A., Sciortino, V., … & Rodeghiero, F. (2020). Clinical recommendations for the diagnosis and management of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood reviews, 45, 100671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2020.100671

30. Lechner, K., Jäger, U., Panzer, S., Granditsch, G., Drach, J., Gessl, A., … & Diringer, H. (2011). Warm-type autoimmune hemolytic anemia: long-term outcome and prognostic factors in 173 patients. Haematologica, 96(2), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2010.032535

31. Sanz, J., Vicente, A., Fernández de Larrea, C., Ferrer, J., Jarque, I., Lorenzo, I., … & Sanz, G. F. (2007). Long-term outcome of warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia in patients treated upfront with corticosteroids. Annals of hematology, 86(7), 549–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-007-0295-8

32. अहिरवार, एस., Patidar, N., & Mishra, R. (2018). Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia: An enigma. Indian journal of hematology & blood transfusion, 34(2), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12288-017-0878-6

33. Lambert, M. P., Pang, M., & Montero-Julian, F. (2017). Pathogenesis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Transfusion clinique et biologique : journal de la Societe francaise de transfusion sanguine et de therapie cellulaire, 24(4), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tracli.2017.06.008

34. Iuchi, K., & Fujii, J. (2019). Red blood cell oxidative stress and autoimmune hemolytic anemia: the pivotal roles of erythroid Krüppel-like factor and reactive oxygen species. Journal of clinical biochemistry and nutrition, 65(2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.3164/jcbn.19-40

35. Lee, Y., Lee, J., & Koh, E. M. (2014). Defective suppressive activity of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in a murine model of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. PloS one, 9(6), e99112. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099112

36. Richards, C. R., Cooper, R., & Ball, H. J. (2009). Naturally occurring regulatory T cells are not required for the prevention of red blood cell autoimmunity. Immunology and cell biology, 87(7), 546–552. https://doi.org/10.1038/icb.2009.46

37. Howie, S. E., Waldmann, H., & Cobbold, S. P. (2006). Breakdown of peripheral tolerance of red blood cells is sufficient to initiate autoimmune anaemia in mice. The Journal of pathology, 208(2), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1883

38. Arese, P., Turrini, F., & Schwarzer, E. (2005). Oxidative stress and cell death in malaria. Cell death and differentiation, 12 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 1176–1189. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401637

39. Schwarzer, E., Buffet, P. A., Arese, P., & Turrini, F. (2007). Reticulocyte binding of anti-band 3 autoantibodies in autoimmune hemolytic anemia induces eryptosis. Haematologica, 92(1), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.10467

40. Xu, J., Zhao, Y., Liu, L., Wang, D., Zhao, M., & Liu, J. (2013). Increased Th17 cells in patients with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Journal of clinical immunology, 33(2), 431–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-012-9796-x

41. Lee, Y. H., & Song, G. G. (2018). Associations between interleukin-17A polymorphisms and autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a meta-analysis. International journal of rheumatic diseases, 21(1), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13144

42. Lee, Y. H., & Song, G. G. (2017). Association between interleukin-23 receptor polymorphisms and autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a meta-analysis. Lupus, 26(7), 762–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203316676371

43. Lee, Y. H., & Song, G. G. (2017). Association between interleukin-6 receptor polymorphisms and autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a meta-analysis. Human immunology, 78(7), 472–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humimm.2017.04.013

44. Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhou, Q., Zhang, Y., Chen, J., & Qin, Z. (2015). T follicular helper cells and T follicular regulatory cells in autoimmune diseases. Journal of immunology research, 2015, 659593. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/659593

45. Machado-Neto, J. A., Silva, M. G., Sandrin-Garcia, P., Ribeiro, G. F., Bonasser Filho, F., de Souza, C. A., … & Voltarelli, J. C. (2020). Clonal expansions of CD8+ T cells are present in autoimmune hemolytic anemia and persist during remission. Clinical immunology (Orlando, Fla.), 211, 108332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2019.108332

46. Cusick, M. F., Libbey, J. E., & Fujinami, R. S. (2012). Molecular mimicry as a mechanism of autoimmune disease. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology, 42(1), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-011-8299-x

47. Morris, C. R., Ashley-Koch, A., & Brown, L. J. (2003). Molecular mimicry by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120: implications for human immunodeficiency virus type 1-associated autoimmune thrombocytopenia. Blood, 101(5), 1744–1749. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-07-2179

48. Moore, R. D., Allen, J. R., & Jett, B. W. (1998). Thrombocytopenia in patients with HIV infection. Predictors, response to therapy, and clinical outcome. The American journal of medicine, 105(3), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00237-1

49. Warnatz, K., & Reth, M. (2014). B cell tolerance in humans: lessons from defects in tolerance checkpoints. Current opinion in immunology, 27, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2014.01.005

50. Conley, M. E., Notarangelo, L. D., & Etzioni, A. (2020). Primary Immunodeficiencies. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(20), 1935–1950. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1917061

51. Oliveira, J. B., Bleesing, J. J., Meyer, N. C., Grommes, J., Cabral-Marques, O., Margraf, S., … & Grimbacher, B. (2010). T regulatory cell defects in patients with CD25-FOXP3- autoantibody-mediated autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 126(5), 1009–1020.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.043

52. Iuchi, K., Okada, Y., Nabekura, T., Awai, Y., Hara, S., Hosoya, K., … & Fujii, J. (2013). Cytoplasmic Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase deficiency causes oxidative stress and autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Nature communications, 4, 2798. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3798

53. Okada, Y., Iuchi, K., Nabekura, T., Fujii, M., Kawabata, T., Yoshikawa, A., … & Fujii, J. (2015). Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation promote autoantibody production against red blood cells in cytoplasmic Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase-deficient mice. Journal of autoimmunity, 58, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2015.03.003

54. Iuchi, K., Imamura, R., Nishikawa, M., Weber, T. J., McKenzie, R. C., & Fujii, J. (2017). Erythroid-specific overexpression of human Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase ameliorates symptoms of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in mice. Redox biology, 11, 543–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2017.01.015

55. Chen, Q., Yan, M., Zhou, W., Zhang, L., & Xiong, S. (2019). Plasma free heme promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation via reactive oxygen species signaling in hemolytic diseases. Free radical biology & medicine, 130, 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.11.030

56. Buerck, J., Wossmann, J., Passler, J., Richter, K., Borgmann, J., Claus, R. A., … & Brückner, C. S. (2019). High shear stress induces erythrocyte aging via band 3 tyrosine phosphorylation and naturally occurring antibodies. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 23(1), 658–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13982

57. Bosman, G. J., & Kay, M. M. (1988). Erythrocyte aging: a cell and molecular biology perspective. Physiological reviews, 68(4), 1277–1353. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1988.68.4.1277

58. Kriebardis, A. G., Antonelou, M. H., Stamoulis, K. E., Economou-Petersen, E., & Margaritis, L. H. (2008). RBC-derived vesicles during storage: ultrastructure, protein mapping, oxidation, and signaling. Transfusion, 48(9), 1943–1956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01771.x

59. Rubin, O., Janvier, R., Larnaud, C., Loy, J., Boyer, O., Babinet, J., … & Lionnet, F. (2008). Red blood cell microparticles promote procoagulant activity and thrombin generation via factor V. Transfusion, 48(8), 1744–1754. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01687.x

60. Michaux, J. L., Dierlamm, J., Wlodarska, I., Poppe, B., Taghon, T., Van Den Berghe, H., & Marynen, P. (1995). Trisomy 3, trisomy 18 and t(14;18) are frequent chromosomal changes in marginal zone lymphoma of splenic and nodal origin. Leukemia, 9(12), 2148–2152.

61. Swerdlow, S. H., Ghia, P., Rosenquist, R., & de Jong, D. (2018). Clonal and cellular heterogeneity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: impact on biology and clinical outcome. Blood, 132(24), 2625–2632. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-03-815616

62. Rossi, D., Rasi, S., Spina, V., Bruscaggin, A., Monti, S., Bassi, S., … & Gaidano, G. (2013). Trisomy 3 and trisomy 18 are recurrent chromosomal abnormalities in cold agglutinin disease. Haematologica, 98(7), 1130–1134. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2012.081680

63. Rossi, D., Spina, V., Gaidano, G., & Dalla-Favera, R. (2012). Marginal zone lymphomas. Blood, 120(13), 2593–2602. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-03-349277

64. Mauro, F. R., Gozzetti, A., Giannarelli, D., Paoloni, F., Pettinari, I., Molica, S., … & Gattei, V. (2017). Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical and biological features, and survival impact of treatments. Haematologica, 102(1), 154–163. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2016.151789

65. Potter, K. N., Stevenson, F. K., & Sutton, L. A. (2015). Stereotyped rheumatoid factor immunoglobulins in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: implications for disease biology and therapy. Haematologica, 100(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2014.113277

66. Sutton, L. A., Corcoran, M., Wright, G.,্ল রাইট, জি.,্ল,্ল,্ল,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,্ব,