Differential diagnosis has long been a cornerstone of medical education, guiding physicians from initial assessment to final diagnosis. For experienced clinicians, this process often begins even before meeting the patient, with a mental list of potential diagnoses refined by the patient’s presentation, demographics, and specific clinical findings.

However, medical training predominantly occurs in tertiary care settings, often led by specialists. This environment, while fostering expertise in specialized areas, may not fully address the breadth of conditions encountered in primary care. Medical students might graduate without managing common primary care issues, highlighting a gap in practical experience relevant to family medicine.

To bridge this gap, we introduce a series of guides in Canadian Family Physician focusing on the top 10 symptoms prompting patient visits to family doctors. These guides are based on a unique 4-year database, the Amsterdam Transition Project, from the Netherlands. Drs. Inge Okkes and Henk Lamberts meticulously tracked patient symptoms until a definitive diagnosis was reached in primary care settings. This database uniquely utilizes the International Classification for Primary Care (ICPC), accommodating undifferentiated and psychosomatic illnesses, making it particularly relevant to general practice. Such longitudinal data linking initial symptoms to eventual diagnoses in primary care is rare, especially in a Canadian context.

Each guide includes heuristic strategies to aid in diagnosing common symptoms while considering less frequent but serious conditions. These strategies are drawn from clinical experience and established medical texts, offering differential diagnoses for both acute and chronic symptom presentations. They also highlight red flags and reassuring features to refine diagnostic approaches.

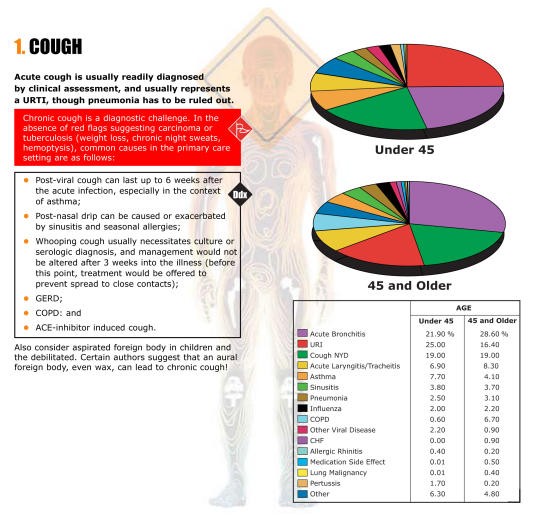

Visual representation of diagnostic incidence rates for frequent symptoms encountered in primary care settings, sourced from the Amsterdam Transition Project.

Visual representation of diagnostic incidence rates for frequent symptoms encountered in primary care settings, sourced from the Amsterdam Transition Project.

A potential limitation is the assumption that primary care populations in the Netherlands and Canada are comparable. While we believe this is a reasonable starting point, better Canadian data are needed.

This resource aims for wide distribution and utilization, accessible via the University of Ottawa’s website. We encourage feedback and hope this initiative stimulates the development of Canadian data collection methods to further refine primary care diagnostic practices.