Introduction

The cornerstone of effective HIV control programs, particularly in regions with constrained resources, lies in accurate HIV diagnosis. Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) have become indispensable tools in HIV testing and counseling (HTC) programs within settings where laboratory infrastructure is limited [[1](#CIT0001)]. Their advantages are clear: low cost, no requirement for cold chain storage, minimal operational training, and the ability to deliver same-day results [[2](#CIT0002),3]. Consequently, RDT-based algorithms are ideally suited for resource-limited environments that lack the sophisticated laboratory facilities and the human and financial capital necessary for more complex diagnostic methods like enzyme-linked immuno-sorbent assays (ELISA) or immunoblots. To guide HIV diagnosis in these contexts, the World Health Organization (WHO) advocates for a sequential approach, utilizing two or three RDTs depending on the HIV prevalence of the setting [[1](#CIT0001)]. However, despite these recommendations, many nations still rely on serial tiebreaker algorithms, where an HIV-positive diagnosis is rendered if two out of three RDTs yield positive results [[4](#CIT0004)].

The WHO further stipulates that serological assays or RDTs used for HIV diagnosis must achieve a minimum sensitivity of 99%. Specifically, the initial RDT should exhibit a specificity of at least 98%, while subsequent RDTs in the algorithm should reach a specificity threshold of 99%. Despite the demonstrated efficacy of numerous individual RDTs in WHO evaluations [[2](#CIT0002),3], reports of false-positive outcomes have emerged from projects undertaken by humanitarian organizations like Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) [[5](#CIT0005)–7], and other entities [[7](#CIT0007)–17]. A false-positive HIV diagnosis carries significant psychological trauma for individuals and can lead to inappropriate and potentially harmful treatment initiation [[6](#CIT0006)]. Furthermore, the communication of false-positive results, even if attributable to technical limitations of the tests, can erode patient trust in HTC centers [[6](#CIT0006)].

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of HIV testing algorithms in real-world scenarios, we conducted a standardized multi-center study across six sites in sub-Saharan Africa. This research aimed to assess the effectiveness of routinely employed HIV diagnostic algorithms at each site under typical operational conditions. Our objectives included evaluating the accuracy of site-specific algorithms, determining the precision of frequently used RDTs in controlled lab settings, and comparing observed performance in routine practice and ideal conditions against WHO recommended benchmarks. This article focuses on presenting the diagnostic accuracy of the algorithms implemented at these sites in routine conditions, benchmarked against a state-of-the-art diagnostic algorithm from the AIDS reference laboratory at the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM) in Antwerp, Belgium.

Methods

Study Settings

This multi-site study was conducted across six HTC facilities in sub-Saharan Africa: (a) Centre Communautaire Matam in Conakry, Guinea; (b) Madi Opei Clinic and Kitgum Matidi Clinic in Kitgum, Uganda; (c) Homa Bay District Hospital in Homa Bay, Kenya; (d) Arua District Hospital in Arua, Uganda; (e) Nylon Hospital in Doula, Cameroun; and (f) Baraka Hospital in Baraka, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). These sites provide both voluntary and provider-initiated HIV testing services. Several sites reported high positivity rates, potentially influenced by targeted testing of spouses of known HIV-positive individuals and their role as primary HIV facilities attracting diverse risk profiles.

Study Population and Inclusion

The study population comprised all clients aged five years and older who presented for HIV testing at the participating HTC sites and provided informed written consent. Participants were also asked to consent separately for tracing in the event of a misdiagnosis.

Following enrollment, participants received counseling and HIV testing according to the specific protocols and testing algorithms of each site. Additionally, blood samples were collected and processed to obtain EDTA plasma, which was stored at −20°C for subsequent transfer to the reference laboratory.

Sample Size and Sampling Strategy

A minimum sample size of 200 HIV-positive and 200 HIV-negative samples, as determined by the site algorithms, was targeted from each study location. This calculation was based on an assumed sensitivity and specificity of 98% for both sample sets, allowing for a 95% confidence interval of ≤±2% for both measures.

In sites with HIV prevalence between 40% and 60%, all consecutive samples were collected, with the total sample size calculated based on prevalence to ensure at least 200 samples in each HIV status category (calculated as the higher of 200/p or 200/(1 − p), capped at a maximum of 500 samples). This target was increased by 10% to account for potential sample loss or integrity issues during shipment.

For sites with prevalence below 40%, a subset of HIV-positive and HIV-negative samples was collected based on the local algorithm results. Assuming a conservative misdiagnosis rate of 10% due to expected algorithm accuracy, a subsample of 220 HIV-positive and 220 HIV-negative samples was collected. This was designed to yield at least 200 true-positive and 200 true-negative samples. All samples with inconclusive algorithm results (discordant results in non-tiebreaker sites) were also collected, along with a backup sample from each participant to address shipment issues or facilitate on-site retesting. Participants who were misdiagnosed and consented to tracing were contacted, and with their consent, a new sample was collected and tested to rule out clerical or other errors.

Testing Strategies and Algorithms at Study Sites

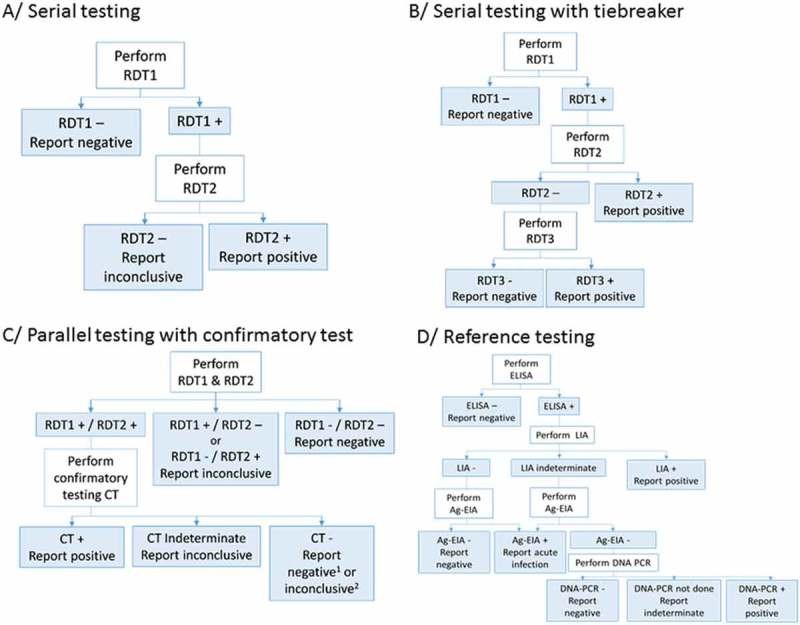

The HIV testing strategies varied across the six study sites, including serial and parallel testing approaches, with and without confirmatory testing (Table 1 and Figure 1). Sample types used included capillary whole blood and EDTA plasma. Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA) was consistently used as the initial test across all sites, while parallel testing with Determine HIV-1/2 and another RDT was implemented at Baraka and Kitgum. Subsequent tests in the algorithms included ImmunoFlow HIV 1–HIV 2 (Core Diagnostics, UK), Uni-Gold HIV (Trinity Biotech, Ireland), HIV 1/2 Stat-Pak (Chembio, USA), ImmunoComb II HIV 1&2 BiSpot (Orgenics, Israel), or GS HIV-1/HIV-2 PLUS O EIA (Bio-Rad, USA), as detailed in Table 1. All tests were administered and interpreted by local program staff, including laboratory technicians and counselors routinely performing HIV testing. No specific training on test procedures was provided as part of the study protocol to ensure results were representative of routine testing practices.

Table 1. HIV testing strategy and algorithms per study site.

| Conakry, Guinea | Kitgum, Uganda | Arua, Uganda | Homa Bay Kenya | Douala, Cameroun | Baraka, DRC | Baraka*, DRC | Kitgum*, Uganda | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testing strategy | Serial | Serial with tie-breaker | Serial with tie-breaker | Serial with tie-breaker | Serial | Serial | Parallel with confirmatory testing | Parallel with confirmatory testing |

| Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA) | Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA) | Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA) | Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA) | Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA) | Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA) | Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA) | Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA) | |

| Testing algorithm | ImmunoFlow HIV-1–HIV-2 (Core Diagnostics, UK) | Uni-Gold HIV(Trinity Biotech, Ireland) | HIV-1/2 Stat-Pak (Chembio, USA) | Uni-Gold HIV (Trinity Biotech, Ireland) | ImmunoComb II HIV-1&2 BiSpot (Orgenics/Alere, Israel) | Uni-Gold HIV (Trinity Biotech, Ireland) | Uni-Gold HIV (Trinity Biotech, Ireland) | Uni-Gold HIV (Trinity Biotech, Ireland) |

| If discordant: retest in 6 weeks | If discordant: HIV 1/2Stat-Pak (Chembio, USA) | If discordant: Uni-Gold HIV (Trinity Biotech, Ireland) | If discordant: GS HIV-1/HIV-2 PLUS O EIA (Bio-Rad, USA) at CDC, Kisumu, Kenya | If discordant: retest in 6 weeks | If discordant: retest in 6 weeks | On all double positives ImmunoComb II HIV 1&2 CombFirm (Orgenics/Alere, Israel) | On all double positives: ImmunoComb II HIV 1&2 CombFirm (Orgenics/Alere, Israel) | |

| Sample type | EDTA plasma | EDTA plasma | Capillary whole blood | Capillary whole blood | EDTA whole blood | Capillary whole blood | EDTA plasma | EDTA plasma |

DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo.

*Algorithm using a simple confirmatory assay (ImmunoComb II HIV 1&2 CombFirm, Orgenics, Israel) with an alternative interpretation by Médecins sans Frontières.

Figure 1. Flow charts of HIV testing strategies and algorithms used.

Figure 1. Flow charts of HIV testing strategies and algorithms used.

Figure 1. Flow charts of HIV testing strategies and algorithms used.

RDT: Rapid diagnostic test; CT: confirmatory test; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; LIA: line immunoassay; Ag-EIA: antigen-enzyme immunoassay; DNA-PCR: deoxyribonucleic acid–polymerase chain reaction. 1In Baraka, DRC; 2in Kitgum, Uganda.

In Kitgum and Baraka, MSF also implemented an alternative algorithm utilizing ImmunoComb II HIV 1&2 CombFirm (Orgenics, Israel) as a simplified confirmatory test subsequent to two reactive RDT results. The ImmunoComb assay, an indirect solid-phase enzyme immunoassay (EIA), detects markers for p24 (gag), p31 (pol), and env-derived protein spots: gp41, gp120, and gp36. The interpretation of ImmunoComb results was modified from the manufacturer’s instructions, based on stringent criteria from a prior evaluation [[7](#CIT0007)]. Specifically, a reaction with 3–4 spots was considered positive, 1–2 spots indeterminate, and no reaction negative. The gp36 marker was excluded from this alternative interpretation.

Reference Standard

The reference standard algorithm at the AIDS reference laboratory at ITM, Antwerp, Belgium, used an ELISA test (Vironostika® HIV Uni-Form II Ag/Ab, bioMérieux, France) for initial screening of plasma samples [[2](#CIT0002)]. All reactive samples were then confirmed using a Line-Immunoassay (LIA, INNO-LIA HIV I/II Score, Innogenetics NV, Ghent, Belgium) [[2](#CIT0002),18–20].

The INNO-LIA HIV I/II Score is designed to confirm the presence of antibodies against HIV type 1 (HIV-1), including group O viruses, and type 2 (HIV-2). It detects antibodies against gp120, gp41, p31, p24, p17, gp105, and gp36.

Samples that were negative or indeterminate by INNO-LIA HIV I/II Score were further tested with an antigen-enzyme immunoassay (Ag-EIA, INNOTEST HIV Antigen mAb, Innogenetics NV, Ghent, Belgium) to rule out acute infections [[2](#CIT0002)].

A sample was classified as HIV negative if both LIA and Ag-EIA results were negative. An indeterminate final result was assigned if the LIA was indeterminate and the Ag-EIA was negative. A potential seroconversion or acute infection was indicated if the LIA was negative or indeterminate, and the Ag-EIA was positive (confirmed by neutralization). If the LIA confirmation could not differentiate between HIV-1 and HIV-2 but indicated HIV infection, the sample underwent in-house HIV DNA-PCR for HIV-1 and HIV-2. Positive DNA-PCR results for HIV-1, HIV-2, or both, led to classification as positive for HIV-1, HIV-2, or both, respectively.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Data entry was performed at all study sites using EpiData 3.1 software (EpiData, Odense, Denmark). At ITM, data were collected in Excel files. Data entry accuracy was monitored at both ITM and study sites through double-checking by a data clerk. Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values were calculated by comparing the results of the testing algorithm at each site to the reference standard algorithm. Participants with inconclusive results from either on-site or reference algorithms, as well as those diagnosed with acute infection by the reference algorithm, were excluded from performance analyses. For sites where the sampling strategy introduced verification bias (Douala, Arua, Kitgum), a Bayesian correction method proposed by Zhou [[21](#CIT0021)] was applied.

Ethics

The study received ethical approval from the MSF Ethics Review Board and ethics committees in each of the five participating countries. Separate written informed consent was obtained for study participation and for tracing in case of misdiagnosis.

Results

Between August 2011 and January 2015, a total of 14,015 clients were tested for HIV across the six HTC sites, with 2786 (19.9%) included in this study (Table 2). The median age of participants was 30 years (IQR: 22–42), and 38.1% were male (IQR: 29.6–48.2%). The majority of participants were self-referred (58.3%) or referred by a partner (18.6%). Provider-initiated testing accounted for referrals from inpatient (11.9%), outpatient (1.7%), antenatal care (6.4%), and tuberculosis clinics (3.0%) within the same health facilities (Table 2).

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics by study site.

| Conakry, Guinea | Kitgum, Uganda* | Arua, Uganda | Homa Bay Kenya | Douala Cameroun | Baraka, DRC* | Total** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study period | August 2011–October 2012 | September 2011–April 2012 | July 2012–January 2013 | August 2012–February 2013 | August 2013–February 2014 | October 2012–January 2015 | |

| Total tested at site | |||||||

| Total, n | 2033 | 3159 | 2971 | 1003 | 1239 | 3610 | 14,015 |

| Positive, n (%) | 574 (28.2) | 332 (10.5) | 386 (13.0) | 372 (37.1) | 396 (32.0) | 288 (8.0) | 2348 (16.8) |

| Negative, n (%) | 1447 (71.2) | 2827 (89.5) | 2585 (87.0) | 617 (61.5) | 826 (66.7) | 3252 (90.1) | 11,554 (82.4) |

| Inconclusive, n (%) | 12 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (1.4) | 17 (1.4) | 70 (1.9) | 113 (0.8) |

| Offered to participate | |||||||

| Total, n | 724 | 565 | 750 | 735 | 513 | 559 | 3846 |

| Reasons for non-inclusion | |||||||

| Offered to participate; total, n | 724 | 565 | 750 | 735 | 513 | 559 | 3846 |

| Insufficient sample | 260 | 0 | 22 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 296 |

| Refusal to participate | 8 | 74 | 285 | 232 | 34 | 62 | 695 |

| Excluded due to anaemia | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Protocol violation | 0 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49 |

| Unknown/Other | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 16 |

| Included in the study | |||||||

| Total, n | 446 | 438 | 443 | 500 | 462 | 497 | 2786 |

| Age and gender | |||||||

| Median age (IQR) | 29 (22–39) | 30 (24–39) | 29 (23–37) | 30 (23–40) | 31 (25–41) | 30 (23–39) | 30 (24–39) |

| Males, n (%) | 132 (29.6) | 176 (40.3) | 213 (48.2) | 201 (40.2) | 163 (35.3) | 177 (35.6) | 1062 (38.1) |

| Entry mode | |||||||

| Volontary testing, n (%) | 0 (0) | 323 (73.90) | 443 (100) | 459 (91.8) | 211 (45.7) | 187 (37.8) | 1623 (58.3) |

| Spouse, n (%) | 238 (53.4) | 20 (4.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 251 (54.3) | 10 (2.0) | 519 (18.6) |

| Referred – TB clinic, n (%) | 57 (12.8) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 21 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.6) | 83 (3.0) |

| Referred – IPD, n (%) | 33 (7.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 297 (59.8) | 330 (11.9) |

| Referred – OPD, n (%) | 13 (2.9) | 33 (7.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 46 (1.7) |

| ANC, n (%) | 105 (23.3) | 54 (12.4) | 0 (0) | 20 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 179 (6.4) |

| Other, n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.2) |

HTC: HIV Testing and Counseling; ANC: Antenatal Care; DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo.

* Not the Local/National/Ministry of Health standard algorithm has been used in this calculation but an algorithm adjusted by MSF according to previous research on diagnostic accuracy of available HIV tests.

**The figures from the algorithm used by MSF in Kitgum and Baraka have been used to calculate the totals.

HIV positivity rates across sites ranged from 8.0% in Baraka to 63.7% in Conakry (Table 2). Reference laboratory testing of 2786 specimens identified 1281 as HIV-1 positive, 1 as HIV-2 positive, 25 as HIV-positive (undifferentiated), 2 as acute infections, 3 as inconclusive, and 1474 as negative.

After adjusting for the under-representation of negative results and excluding inconclusive results and acute infections, the sensitivity of the testing algorithms ranged from 89.5% in Arua to 100% in Douala and Conakry (Table 3). Specificity varied from 98.3% in Douala to 100% in Conakry. Positive predictive values (PPV) ranged from 96.4% in Douala to 100% in Conakry, while negative predictive values (NPV) ranged from 98.3% in Arua to 100% in Conakry, Douala, and Baraka.

Table 3. HIV testing algorithm performance per study site.

| Conakry, Guinea | Kitgum*, Uganda | Kitgum*’#, Uganda | Arua*, Uganda | Homa Bay, Kenya | Douala*, Cameroun | Baraka*, DRC | Baraka*’#, DRC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included in the study based on HIV status tested at site | ||||||||

| Total, n | 446 | 438 | 438 | 443 | 500 | 462 | 497 | 497 |

| Positive, n (%) | 222 (49.8) | 218 (49.7) | 216 (49.6) | 212 (47.9) | 223 (44.6) | 222 (48.1) | 226 (45.5) | 221 (44.5) |

| Negative, n (%) | 220 (49.3) | 220 (50.3) | 220 (50.2) | 231 (52.1) | 277 (55.4) | 230 (49.8) | 219 (44.1) | 220 (44.2) |

| Inconclusive, n (%) | 4 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (2.2) | 52 (10.5) | 56 (11.3) |

| Results based on reference standard | ||||||||

| Positive, n (%) | 222 (49.8) | 214 (48.9) | 214 (48.9) | 212 (47.9) | 224 (44.8) | 214 (46.3) | 221 (44.5) | 221 (44.5) |

| Negative, n (%) | 224 (50.2) | 222 (50.7) | 222 (50.7) | 230 (51.9) | 276 (55.2) | 247 (53.5) | 275 (55.3) | 275 (55.3) |

| Indeterminate n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Acute infection (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diagnostic performance of algorithm at study site | ||||||||

| Sensitivity % (95% CI) | 100 (98.3–100) | 96.2 (78.1–99.4) | 96.2 (78.2–99.4) | 89.5 (76.2–95.8) | 98.7 (96.1–99.7) | 100 (98.3–100) | 100 (98.3–100) | 100 (98.3–100) |

| Specificity % (95% CI) | 100 (98.3–100) | 99.8 (99.4–99.9) | 99.9 (99.6–100) | 99.8 (99.3–99.9) | 99.3 (97.4–99.9) | 98.3 (96.7–99.1) | 98.5 (95.7–99.5) | 99.9 (99.7–100) |

| PPV % (95% CI) | 100 (98.3–100) | 98.2 (95.3–99.5) | 99.1 (96.7–99.9) | 98.6 (95.9–99.7) | 99.1 (96.8–99.9) | 96.4 (93.0–98.4) | 97.8 (94.9–99.3) | 99.5 (97.5–100) |

| NPV % (95% CI) | 100 (98.3–100) | 99.1 (96.7–99.9) | 99.5 (97.5–100) | 98.3 (95.6–99.5) | 98.9 (96.9–99.8) | 100 (98.4–100) | 100 (98.3–100) | 100 (98.3–100) |

| False positive, n | 0 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 1 |

| False negative, n | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo.

*Adjusted results considering verification bias and excluding indeterminate results on-site and seroconverters by the reference algorithm.

#Algorithm using a simple confirmatory assay (ImmunoComb II HIV 1&2 CombFirm, Orgenics, Israel) with an alternative interpretation by Médecins sans Frontières.

In total, 24 (0.9%) participants received a misdiagnosis across all sites, ranging from 0 to 8 per site (0–1.7%), comprising 16 false-positive and 8 false-negative results. Six false-negative specimens tested positive upon retesting with the on-site algorithm using backup samples (Table 4). Of 16 false-positive specimens retested, 10 remained positive (reactive with the first two RDTs), and 2 remained positive with only one RDT. In Douala, all eight false-positive cases were traced, and new samples were collected to exclude clerical errors. One client’s retest was negative, one was indeterminate, and six remained reactive with both RDTs, despite all being negative by the reference algorithm (Table 4).

Table 4. Detailed testing results of false-negative and false-positive misdiagnosed participants at site.

| Study site | Sample ID | Test result on site | Status on site | ELISA results reference laboratory | LIA results reference laboratory | Status by reference laboratory | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| False-negative misdiagnosed participants | |||||||

| Kitgum | 196 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveStat-Pak: non-reactive | HIV negative* | OD: 1.766CO: 0.161OD/CO: 10.97Result: reactive | sgp120: −gp41: 1+p31: −p24:1+p17:2+ | HIV positive | No backup sample |

| Arua | 368 | Determine: non-reactive | HIV negative | OD: 3.000CO: 0.179OD/CO: ≥16.76Result: reactive | sgp120: 2+gp41: 3+p31: 2+p24: 3+p17: 3+sgp105: −gp36: − | HIV-1 positive | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: reactiveUni-Gold: reactive |

| Arua | 453 | Determine: non-reactive | HIV negative | OD: 3.000CO: 0.186OD/CO: ≥16.13Result: reactive | sgp120: 2+gp41: 4+p31: −p24: 4+p17: 4+sgp105: −gp36: − | HIV-1 positive | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: reactiveUni-Gold: reactive |

| Arua | 454 | Determine: non-reactive | HIV negative | OD: 3.000CO: 0.186OD/CO: ≥16.13Result: reactive | sgp120: 2+gp41: 4+p31:3+p24: 3+p17: −sgp105: −gp36: − | HIV-1 positive | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: reactiveUni-Gold: reactive |

| Arua | 611 | Determine: non-reactive | HIV negative | OD: 3.000CO: 0.173OD/CO: ≥17.34Result: reactive | sgp120: 2+gp41: 3+p31: −p24: 3+p17: 2+sgp105: −gp36: − | HIV-1 positive | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: non-reactiveUni-Gold: reactive |

| Homa-Bay | 394 | Determine: non-reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactive | HIV negative | OD: 3.000CO: 0.162OD/CO: 18.52Result: reactive | sgp120: 3+gp41: 3+p31: 2+p24: 3+p17: 3+sgp105: −gp36: − | HIV-1 positive | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: reactive |

| Homa-Bay | 439 | Determine: non-reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactive | HIV negative | OD: 3.000CO: 0.162OD/CO: 18.52Result: reactive | spg120: 2+gp41: 3+p31: 2+p24: 4+p17: 3+spg105: −gp36: − | HIV-1 positive | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: reactive |

| Homa-Bay | 469 | Determine: non-reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactive | HIV negative | OD: 3.000CO: 0.162OD/CO: 18.52Result: reactive | spg120: 2+gp41: 3+p31: −p24: 3+p17: 3+spg105: −gp36: − | HIV-1 positive | No backup sample |

| False-positive misdiagnosed participants | |||||||

| Kitgum | 240 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: reactiveImmunoComb CombFirm: reactive (p24+, p31+, gp120+, gp41+, p31−, gp36−) | HIV positive | OD: 0.06CO: 0.174OD/CO: 0.34Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | No backup sample |

| Kitgum | 596 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: reactiveImmunoComb CombFirm: reactive (p24+, gp120 +, gp41+, p31−, gp36−) | HIV-positive | OD: 0.066CO: 0.180OD/CO: 0.37Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | No backup sample |

| Arua | 342 | Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.049CO: 0.179OD/CO: 0.27Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: non-reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactive |

| Arua | 529 | Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.057CO: 0.170OD/CO: 0.34Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactive |

| Arua | 622 | Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.067CO: 0.173OD/CO: 0.39Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: non-reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactive |

| Homa-Bay | 5 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveEIA GS: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.084CO: 0.261OD/CO: 0.32Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactive |

| Homa-Bay | 16 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.119CO: 0.261OD/CO: 0.46Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample:Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: reactiveThe ELISA test at CDC in Kisumu was negative on the same sample. In addition, a western blot (GS HIV-1 Western Blot, No. 32508, Bio-Rad, USA) was carried out at CDC and had an indeterminate result: gp160+, gp120−, p65−, p55/51−, gp41−, p40+, p31+/−, p24−, p18− |

| Douala | 48 | Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.043CO: 0.153OD/CO: 0.28Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample same result as initial testingSecond sample approx. three months later was collected:Determine: reactiveBiSpot: non-reactiveELISA at reference laboratory: non-reactive |

| Douala | 68 | Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.050CO: 0.153OD/CO: 0.33Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample same result as initial testingSecond sample approx. three months later was collected:Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactiveELISA at reference laboratory: non-reactive |

| Douala | 307 | Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.053CO: 0.154OD/CO: 0.34Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample same result as initial testingSecond sample approx. two months later was collected:Determine: non-reactiveELISA at reference laboratory: non-reactive |

| Douala | 356 | Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.058CO: 0.166OD/CO: 0.35Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample same result as initial testingSecond sample approx. three months later was collected:Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactiveELISA at reference laboratory: non-reactive |

| Douala | 381 | Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.055CO: 0.166OD/CO: 0.33Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample same result as initial testing.Second sample approx. 6 weeks later was collected:Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactiveELISA at reference laboratory: non-reactive |

| Douala | 411 | Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.048CO: 0.154OD/CO: 0.31Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample same result as initial testingSecond sample approx. two months later was collected:Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactiveELISA at reference laboratory: non-reactive |

| Douala | 445 | Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 3.122CO: 0.154OD/CO: 20.27Result: reactive | sgp120: −gp41: 2+p31: −p24: −p17: −sgp105: −gp36: −Innotest: non-reactive | HIV negative | Backup sample same result as initial testingSecond sample approx. 6 weeks later was collected:Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactiveELISA at reference laboratory: reactiveINNO-LIA: sgp120: −, gp41: 2+, p31: −, p24: −, p17: −, sgp105: −, gp36: −Innotest: non-reactive |

| Douala | 464 | Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactive | HIV positive | OD: 0.060CO: 0.154OD/CO: 0.39Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | Backup sample same result as initial testingSecond sample approx. 4 weeks later was collected:Determine: reactiveBiSpot: reactiveELISA at reference laboratory: non-reactive |

| Baraka | 479 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: reactive(both on capillary whole blood and plasma)ImmunoComb CombFirm: reactive (p24+, p31−, gp120+, gp41+, p31−, gp36−) | HIV positive | OD: 0.048CO: 0.149OD/CO: 0.32Result: non-reactive | – | HIV negative | No backup sample |

*HIV negative by Ministry of Health algorithm and inconclusive by alternative Médecins sans Frontières algorithm.

CO: Cutoff; OD: optical density; Determine: Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA); Uni-Gold: Uni-Gold HIV (Trinity Biotech, Ireland); Stat-Pak: HIV 1/2 Stat-Pak (Chembio, USA); ImmunoComb CombFirm = ImmunoComb CombFirm II HIV 1&2 CombFirm (Orgenics, Alere, Israel); EIA GS: GS HIV-1/HIV-2 PLUS O EIA (Bio-Rad, USA); BiSpot: ImmunoComb CombFirm II HIV 1&2 BiSpot (Orgenics, Alere, Israel).

Detailed results for 99 participants with discordant initial RDT results are presented in Table 5. The number of discordant results varied by site, from four in Conakry to 54 in Baraka, the latter influenced by the inclusion of all inconclusive results and a longer recruitment period. However, the proportion of inconclusive results among all tested clients in Baraka (1.9%) was only slightly higher than in other sites with similar inconclusive classifications (Table 2). Among these 99 discordant results, the reference standard classified the majority (n=91) as negative (Table 5).

Table 5. Detailed testing results of discordant rapid test results per study site.

| Study site | No. (%) Discordant samples | Sample IDs | Test result on site | HIV status on site | Test results reference laboratory | HIV status by reference laboratory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conakry | 4 (0.9) | 151, 153, 198, 327 | Determine: reactiveImmunoFlow: non-reactive | Inconclusive | ELISA: non-reactive | HIV negative |

| Kitgum | 10 (2.3) | 82, 617 | Determine: non-reactiveUni-Gold: reactiveStat-Pak: non-reactive | HIV negative | ELISA: non-reactive | HIV negative |

| 114, 123 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveStat-Pak: non-reactive | HIV negative | ELISA: non-reactive | HIV negative | ||

| 138, 519, 559 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveStat-Pak: non-reactive | HIV negative | ELISA: reactiveLIA: non-reactive (sgp120: −, gp41: −, p31: −, p24: −, p17: −, gp105: −, gp36: −) | HIV negative | ||

| 148 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveStat-Pak: reactiveImmunoComb Combfirm: positive (p24+, p31−, gp120+, gp41+, gp36−) | HIV positive | ELISA: reactiveLIA: reactive (sgp120: 3+, gp41: 3+, p31: 2+, p24: 4+, p17: 3+, sgp105: −, gp36) | HIV-1 positive | ||

| 196 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveStat-Pak: non-reactive | HIV negative | ELISA: reactiveLIA: reactive (sgp120: −, gp41: 1+, p31: −, p24: 1+, p17: 2+, sgp105: −, gp36: −) | HIV-1 positive | ||

| 205 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveStat-Pak: reactiveImmunoComb Combfirm: positive (p24+, p31−, gp120+, gp41+, gp36+) | HIV positive | ELISA: reactiveLIA: reactive (sgp120: −, gp41: 2+, p31: −, p24: 2+, p17: −sgp105: −, gp36) | HIV-1 positive | ||

| Arua | 12 (2.7) | 251, 344, 354, 387, 402, 431, 440, 441, 465, 489, 495 | Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: non-reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactive | HIV negative | ELISA: non-reactive | HIV negative |

| 620 | Determine: reactiveStat-Pak: non-reactiveUni-Gold: reactive | HIV positive | ELISA: reactiveLIA: reactive (sgp120: 3+, gp41: 3+, p31: 3+, p24: 2+, p17: 3+, gp105: −, gp36: −) | HIV-1 positive | ||

| Homa-Bay | 9 (1.8) | 5 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveEIA GS: reactive | HIV positive | ELISA: non-reactive | HIV negative |

| 66, 138, 184, 298, 422 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveEIA GS: non-reactive | HIV negative | ELISA: non-reactive | HIV negative | ||

| 170 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveEIA GS: reactive | HIV positive | ELISA: reactiveLIA: reactive spg120: 2+, gp41: 3+, p31: 3+, p24: 4+, p17: 3+, spg105: −, gp36: −) | HIV-1 positive | ||

| 177 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveEIA GS: reactive | HIV positive | ELISA: reactiveLIA: reactive (spg120: 2+, gp41: 2+, p31: 2+, p24: 4+, p17: 3+, spg105: −, gp36: −) | HIV-1 positive | ||

| 449 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactiveEIA GS: reactive | HIV positive | ELISA: reactiveLIA: reactive (spg120: −, gp41: 2+, p31: −, p24: 2+, p17: +, spg105: −, gp36: −) | HIV-1 positive | ||

| Douala | 10 (2.2) | 006, 011, 165, 202, 363, 374, 378, 397, 398, 457 | Determine: reactiveBiSpot: non-reactive | Inconclusive | ELISA: non-reactive | HIV negative |

| Baraka | 54 (10.9) | 24, 28, 56, 68, 83, 84, 85, 96, 98, 104, 105, 120, 128, 139, 140, 147, 160, 161, 174, 184, 191, 196, 197, 203, 228, 231, 239, 260, 277, 296, 300, 318, 320, 328, 334, 341, 364, 367, 368, 370, 376, 389, 396, 408, 409, 420, 429, 443, 444, 471, 472, 474 | Determine: reactiveUni-Gold: non-reactive | Inconclusive | ELISA: non-reactive | HIV negative |

| 86 | Determine: non-reactiveUni-Gold: reactive | Inconclusive | ELISA: reactiveLIA: reactive (sgp120: − gp41: +/−, p31: −, p24: −, p17: −, sgp105: −, gp36: −) | HIV-1 positive | ||

| 476 | Determine: non-reactiveUni-Gold: reactiveImmunoComb Combfirm: positive (p24+, p31−, gp120+, gp41+, gp36−) | Inconclusive | ELISA: reactiveLIA: reactive (sgp120: − gp41: +/−, p31: −, p24: 2+ p17: 1+, sgp105: −, gp36: −) | Inconclusive(no DBS for PCR) |

Determine: Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere, USA); ImmunoFlow: ImmunoFlow HIV 1–HIV 2 (Core Diagnostics, UK); Uni-Gold: Uni-Gold HIV (Trinity Biotech, Ireland); Stat-Pak: HIV 1/2 Stat-Pak (Chembio, USA); ImmunoComb CombFirm: ImmunoComb II HIV 1&2 CombFirm (Orgenics, Alere, Israel); EIA GS: GS HIV-1/HIV-2 PLUS O EIA (Bio-Rad, USA); BiSpot: ImmunoComb II HIV 1&2 BiSpot (Orgenics, Alere, Israel); DBS: dried blood spot.

Of the two clients in Kitgum identified with acute infections, one tested positive by the national algorithm (indeterminate by MSF algorithm), and the other tested negative.

Discussion

Elevated error rates reported in RDT-based HIV testing within resource-limited settings [[5](#CIT0005)–17] motivated this extensive multi-site study to evaluate the performance of HIV testing algorithms in six sub-Saharan African sites. Comparing on-site algorithm results against a recognized reference algorithm from the AIDS reference laboratory at ITM, Antwerp, revealed that algorithm performance at Kitgum, Arua, Douala, and Baraka did not meet the WHO-recommended PPV threshold of ≥99% [[1](#CIT0001)]. However, in Kitgum and Baraka, the 99% PPV threshold was achievable with an alternative algorithm incorporating a simple confirmatory assay.

While sensitivity and NPVs of testing algorithms were excellent (100%) at three sites (Conakry, Douala, and Baraka), other sites exhibited lower sensitivity and NPVs, particularly after adjusting for under-representation of algorithm-negative specimens. For example, in Arua, where fewer than 10% of on-site negatives were included, a single false-negative participant suggested a potential for up to 10 false negatives if all screened negatives had been reference-tested. However, repeat testing of false-negative samples using the same on-site algorithms yielded positive results, except in Kitgum. This implies that procedural errors or test misinterpretation may have contributed to false-negative results in Arua. Alternatively, sample type differences could be a factor; initial testing used capillary whole blood, while backup and reference testing used plasma. Though manufacturers must demonstrate equivalence across sample types, serum/plasma RDTs have been reported to exhibit higher sensitivity but lower specificity than capillary whole blood RDTs [[22](#CIT0022),23].

Suboptimal on-site algorithm specificity and PPV (PPV<99%) were also observed. Several factors could explain this, including low specificity of individual RDTs. Notably, none of the study site algorithms adhered to current WHO HIV testing guidelines [[1](#CIT0001)]. Tiebreaker algorithms, though discouraged by WHO but prevalent in the African region [[4](#CIT0004)], were used at three sites. Tiebreakers are linked to higher false-positive risks [[1](#CIT0001),9,24]. However, only one of 16 false positives in this study was attributed to tiebreaker use; most had reactive results with the first two assays, suggesting shared cross-reactivity issues among tests. While most tests used, except ImmunoFlow and ImmunoComb II HIV 1&2 Combfirm, are WHO prequalified with good specificity in evaluations [[25](#CIT0025)], real-world performance can vary [[5](#CIT0005),7–17].

MSF proposed an alternative algorithm with a simple confirmatory assay to mitigate false positives [[7](#CIT0007)]. In Baraka, this improved specificity and PPV compared to the local algorithm. However, the cost and ease of use of confirmatory assays versus RDT-only algorithms require further evaluation. The WHO’s latest recommendations for low-prevalence settings suggest a third RDT to confirm positive results, potentially enhancing algorithm PPV [[1](#CIT0001)].

While inconclusive results are typically excluded from sensitivity and specificity analyses, their psychological and practical impact necessitates consideration in overall algorithm evaluation. The proportion of inconclusive results in this study should be interpreted cautiously due to sampling strategies. Inconclusive results were only reported in non-tiebreaker sites, ranging from 0.2% to 1.9%, potentially due to geographic or immunological factors [[26](#CIT0026),27], or algorithm variations. Further investigation is warranted.

Current WHO guidelines advise a third RDT for discordant initial RDT results, with a negative result if the third RDT is non-reactive. This approach, not using the third RDT as a tiebreaker, likely reduces inconclusive results, most of which, as shown, were negative by the reference standard.

Study limitations include verification bias from participant selection based on on-site results, which was partially addressed using a Bayesian method by Zhou [[21](#CIT0021)], albeit with wider confidence intervals. Also, while on-site testing used capillary whole blood, backup and reference testing used plasma, limiting investigation into false results. Inconsistent backup sample testing also complicated discerning discrepancies between on-site and reference results.

Conclusions

This comprehensive multi-center study underscores the variable performance of HIV testing algorithms in sub-Saharan Africa. Suboptimal algorithm sensitivities may stem from procedural errors, while inadequate RDT algorithms, as in Douala, can lead to suboptimal specificity and PPV. Beyond quality control, including incubation times, labeling, and batch control, regular validation of HIV RDTs and algorithms is crucial to minimize misdiagnosis risks. National policies should align with current WHO recommendations regarding algorithm design and misdiagnosis mitigation strategies, such as retesting at antiretroviral therapy initiation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all study participants and healthcare staff at each site. We thank MSF’s laboratory working group: Erwan Piriou, Charity Kamau, Pamela Hepple, Pascale Chaillet, Monique Gueguen, Celine Lastrucci, Laurence Bonte, and Roberto de la Tour. We also thank Meggy Verputten, Karla Bil, Annick Antierens, and Suna Balkan at MSF headquarters, and MSF and national ethical review boards. We appreciate Patricia Kahn and Patrick Adams for editing.

Special thanks to study team members and local supporters: J. Mashala, H. Onyango, E. Oyoo, E. Abich, S. Oyugi, J. Amimo, C. Mugo, N. Jaleny, F. Dwallo, S. Matiku, P. Balikagala, Z. Tu, H. Elyas, S. Adega, and B. Kirubi (Homa-Bay, Kenya); S. Noubissi, F. Essomba, P. Ndobo, C. Tchimou, and G. Ehounou (Douala, Cameroon), P. Kahindo, J.J. Mapenzndahei, J. Wazome, A. Uunda, N. Amwabo, L. Byantuku, P. Tawimbi, M. Dialo, and E. Castagna (Baraka, DRC); C. Gba-Foromo (Conakry, Guinea); P. Ongeyowun, M. Baral-Baron, K. Kelly, C. Paye, K. Chipemba, J. Sande, I. Quiles, and V. de Clerck (Arua, Uganda); R. Aupal, R. Olal, Dr Shoaib, Y. Boum, and S. Muhammad (Kitgum, Uganda).

Finally, we thank Annelies Van den Heuvel, Marianne Mangelschots, Valerie De Vos, Maria De Rooy, and Tine Vermoesen, laboratory technicians at ITM.

Biography

C.S. Kosack, A-L. Page, L. Shanks, and K. Fransen designed the study and protocol. C.S. Kosack, A-L. Page, T. Benson, A. Savane, A. Ng’ang’a, B. Andre, and J-P. B. N. Zahinda implemented the study at sites. G. Beelaert and K. Fransen performed lab analysis and data collection at the reference laboratory. C.S. Kosack, A-L. Page, L. Shanks, and K. Fransen prepared the manuscript. T. Benson, A. Savane, A. Ng’ang’a, B. Andre, J-P. B. N. Zahinda, and G. Beelaert contributed to data interpretation and manuscript review. All authors approved the final version.

Funding Statement

MSF’s Innovation Fund funded sample collection, shipment, and analysis at ITM. The sponsor had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or publication decisions. The corresponding author accessed all data and had final responsibility for publication submission.

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

References

[1] World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the diagnosis of HIV infection in infants and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

[2] World Health Organization. WHO prequalification of diagnostics programme. List of prequalified in vitro diagnostic products. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

[3] Pant Pai N, Sharma J, Shivkumar S, Pillay S, Vadnais C, Joseph L, et al. Supervised versus unsupervised rapid HIV testing for antenatal clinics in South Africa: a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2007;4(6):e191. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[4] Peter TF,輸送 van den, Stevens R, Balachandra S, Unnikrishnan B, Zeh C, et al. False-positive HIV diagnoses in resource-limited settings: operational considerations for HIV programmes. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(8):609–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[5] Zachariah R, Tejiokem M-C, Johnson C,伸張 François, Castro KG, Szumilin E, et al. Is a single rapid test enough for diagnosing HIV in resource-poor settings? Findings from rural Cameroon. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(7):819–24. [PubMed]

[6] Vitoria M, Ford N, Gilroy N, Clayden P, Hargreaves S. The lesser evil: weighing the impact of false-positive and false-negative rapid HIV tests in resource-limited settings. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1437–8. [PubMed]

[7] Fransen K, Beelaert G, Lynen L, Broeck J Van den. Evaluation of rapid tests and algorithms for diagnosis of HIV infection in resource-constrained settings: are simpler algorithms better? Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(10):1215–24. [PubMed]

[8] Grabbe LK, Burrell R, Dude A, Brennan A, McAllister J, Moore R, et al. Discordant HIV test results and rates of false-positive rapid HIV tests in a prospective evaluation of point-of-care testing. AIDS. 2011;25(13):1677–83. [PubMed]

[9] Fonjungo PN, Zeh C, Ferrand R, Cavalcante S, Rollins N, Kourtis AP, et al. False-positive HIV rapid diagnostic tests among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(4):286–92D. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[10] Hawkes S, Hall Z, Patou G, Mansoor H, Salter C, Bhutta ZA, et al. Culture, context and the কনটেক্সট politics of implementing rapid syphilis tests in antenatal care: case studies from Bolivia, China, India and Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(Suppl 2):ii40–9. [PubMed]

[11] Homsy J, Kalamya JN, Mukasa B, Weber J, Babirye R, King R, et al. Provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling for TB patients and suspects in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(Suppl 1):29–37. [PubMed]

[12] Jafar TH, Gandhi M, de Jong VD, Naheed A, Nazir N, Karim M, et al. Point-of-care screening for hepatitis B and C virus infection in hemodialysis centers in Pakistan: a multicenter evaluation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(6):1119–26. [PubMed]

[13] Lubbock PB, Batts DH, Wagner RJ, Sande MA. Evaluation of a new rapid point-of-care test for human immunodeficiency virus antibody. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(12):1701–4. [PubMed]

[14] Lugada E, Kajungu H, Raymond M,ាហା Mukadi,組合 Mahler H, Gray RH, et al. Home-based and mobile voluntary counselling and testing for HIV in rural Uganda. Popul Serv Int Res Rep. 2008;(21):1–8.

[15] Rouet F, Ekouevi DK, Chaix M-L, Burgard M, Inwoley A, Toni TD, et al. Accuracy of rapid human immunodeficiency virus assays in early infant diagnosis and in routine clinical care in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(1):63–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[16] Shiboski S, Neilands TB, Catania JA, Dilley JW. False positive HIV test results: the effect of psychological distress and implications for intervention. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9(5):451–60. [PubMed]

[17] Westheimer E, Zucker JR, Bachelet C, Fitzgerald DW, Johnson WD, Jr, Pape JW. Evaluation of a rapid point-of-care HIV antibody assay in Haiti. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(4):485–8. [PubMed]

[18] Debaisieux L, Van Ranst M, Vereecken K, Van Wijngaerden E, Goubau P. Evaluation of the performance of the new Architect HIV Ag/Ab Combo assay. J Clin Virol. 2014;61(4):585–8. [PubMed]

[19] Janssen F, Vereecken K, Debaisieux L, Vodouhe C, Anagonou S, Alary M, et al. Evaluation of the performance of the Determine™ HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo test using dried blood spots. J Virol Methods. 2015;222:93–7. [PubMed]

[20] Janssen F, Vereecken K, Nkengasong J, Behets F, Lynen L, Broeck J Van den. Evaluation of a rapid diagnostic test for simultaneous detection of HIV antibodies and p24 antigen for early detection of HIV infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(7):679.e1–4. [PubMed]

[21] Zhou X-H. Confidence intervals for the sensitivity and specificity at a fixed value of the other parameter in the absence of a gold standard. Stat Med. 1993;12(7):687–99. [PubMed]

[22] Anglemyer A,ッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグッグUGG