The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2023 report brings significant updates for healthcare professionals involved in the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Freely accessible on the GOLD website (www.goldcopd.org), this comprehensive document, along with its pocket guide and teaching slide set (1), incorporates 387 new references, reflecting the latest evidence in the field. This article provides an executive summary of the GOLD 2023 report (1), highlighting clinically relevant aspects and new evidence published since the 2017 executive summary, ensuring clinicians are up-to-date with the best health care guidelines for COPD.

Refined Definition of COPD

The GOLD 2023 report introduces a refined definition of COPD, focusing on the disease’s distinguishing characteristics, separate from epidemiology, causes, risk factors, and diagnostic criteria. This new definition enhances clarity and precision in understanding COPD.

COPD is now defined as a heterogeneous lung condition characterized by chronic respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, cough, sputum production, and/or exacerbations) due to abnormalities of the airways (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) and/or alveoli (emphysema) that cause persistent, often progressive, airflow obstruction. This definition underscores the symptomatic and pathological features of COPD, crucial for accurate health care guidelines and clinical diagnosis.

Pathogenesis and Risk Factors: GETomics in COPD

COPD pathogenesis is understood through the lens of GETomics, representing dynamic, cumulative gene (G) – environment (E) interactions over time (T) that lead to lung damage and altered lung development or aging (4). Identifying these factors is vital for risk assessment and preventive health care guidelines.

Environmental Risk Factors

Cigarette smoking remains a primary environmental risk factor, strongly linked to respiratory symptoms, lung function decline, and COPD mortality (5). However, it’s important to note that less than 50% of heavy smokers develop COPD (6), suggesting other factors are at play. Exposure to secondhand smoke, other tobacco products (pipe, cigar, water pipe) (7–9), and marijuana (10) also contribute to COPD risk (11). Maternal smoking during pregnancy poses risks to fetal lung development, potentially predisposing to future respiratory issues (4, 12).

COPD in nonsmokers, especially prevalent in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), accounts for a significant proportion of cases (60–70%) (13). Globally, non-smoking risk factors contribute to over 50% of COPD burden (13). Household air pollution from biomass fuels (wood, dung, crop residues, coal) used in inefficient stoves is a major concern (14). COPD in nonsmokers often presents differently, affecting more women and younger individuals, with similar symptoms but potentially less emphysema and slower lung function decline compared to smokers. They may also exhibit different inflammatory profiles (13, 17). Further research is crucial to develop targeted interventions and pharmacotherapy for this COPD phenotype (13).

Occupational exposures to dusts, chemicals, and fumes are underrecognized COPD risk factors (18, 19). Studies estimate workplace exposures contribute to a substantial fraction of COPD cases, especially among never-smokers (20). Occupational history should be a key consideration in COPD risk assessment and health care guidelines.

Air pollution, comprising particulate matter (PM), ozone, nitrogen and sulfur oxides, and greenhouse gases, is a major global contributor to COPD, particularly in LMICs (1). The risk is dose-dependent, with no safe threshold. Chronic exposure, even in areas with moderate pollution, accelerates lung function decline and increases COPD risk, especially in vulnerable individuals (21, 22. Air pollution also exacerbates COPD, leading to increased hospitalizations and mortality (23). Public health initiatives to reduce air pollution are essential for COPD prevention and management.

Genetic Risk Factors

α-1 antitrypsin deficiency due to SERPINA1 mutations is the most recognized genetic risk factor (24). The PiZZ genotype, affecting a small percentage of COPD patients (25), is associated with increased risk. Heterozygotes (MZ and SZ) do not have increased COPD risk unless they smoke (26). Other genetic variants with smaller individual effects may collectively increase COPD susceptibility (27). Genetic screening may be considered in specific high-risk populations within health care guidelines.

Lung Function Trajectories and Early Life Factors

Normal lung function follows a trajectory of growth until 20-25 years, a plateau, and then a gradual decline with aging (5, 28). Deviations from this trajectory, influenced by gestational, birth, childhood, and adolescent factors, can impact peak lung function and accelerate decline (28. Lower lung function trajectories are linked to higher morbidity and mortality (29), while higher trajectories are associated with healthier aging (30, 31.

Childhood disadvantage factors like prematurity, low birth weight, maternal smoking, infections, and poor nutrition are critical determinants of peak lung function (32–39. Reduced peak lung function increases later-life COPD risk (32, 40, 41. Approximately half of COPD cases arise from accelerated FEV1 decline, and the other half from impaired lung development (42. Early life interventions to optimize lung development are crucial for long-term respiratory health and should be emphasized in health care guidelines.

Sex and Socioeconomic Status

COPD prevalence is becoming nearly equal in men and women in developed countries (43). Women often report more dyspnea, worse health status, and more exacerbations at similar airflow limitation levels (44. Sex-specific considerations in COPD management are increasingly recognized.

Lower socioeconomic status and poverty are consistently associated with airflow obstruction and COPD risk (45, 46, likely due to increased exposure to pollutants, crowding, poor nutrition, and infections. Addressing socioeconomic disparities is essential for reducing COPD burden within public health care guidelines.

Asthma and Infections

Childhood asthma and atopy may increase adult COPD risk (47, 48. However, poor lung development can mimic asthma symptoms, potentially leading to misdiagnosis. It’s crucial to differentiate true asthma from early COPD manifestations.

Severe childhood respiratory infections are linked to reduced lung function and adult respiratory symptoms (47, 49. Chronic adult bronchial infections, particularly with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, accelerate FEV1 decline (50). Tuberculosis (51 and HIV infection (52 are also significant COPD risk factors in many regions. Infection prevention and management are important aspects of COPD health care guidelines.

Diagnosis of COPD: Spirometry Imperative

COPD diagnosis should be considered in patients with dyspnea, chronic cough, sputum production, recurrent respiratory infections, and risk factor exposure. Forced spirometry demonstrating a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio <0.7 is essential to confirm COPD diagnosis. FEV1 further classifies airflow obstruction severity (GOLD grades 1-4). Spirometry plays a central role in COPD diagnosis and ongoing management as per health care guidelines.

Airflow obstruction is not COPD-specific; it can occur in asthma and other conditions. Clinical context and risk factors are vital for differential diagnosis.

A single spirometry reading with a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio of 0.60-0.80 should be confirmed with repeat spirometry due to potential variability (53, 54). Ratios >0.80 generally rule out COPD based on spirometry criteria.

GOLD favors a fixed FEV1/FVC ratio <0.7 for diagnosis due to its simplicity, independence from reference values, and use in clinical trials informing treatment recommendations. While acknowledging debates about using the lower limit of normal (LLN), GOLD emphasizes the fixed ratio’s practicality and prognostic validity (55–57). Diagnostic simplicity is key for busy clinicians, and spirometry is one component of clinical COPD diagnosis, considered alongside symptoms and risk factors.

Post-bronchodilator spirometry is required for COPD diagnosis and assessment, but assessing bronchodilator reversibility to guide therapy is no longer recommended (58. Reversibility varies over time and doesn’t reliably differentiate COPD from asthma or predict treatment response (59). Withholding inhaled medications before follow-up spirometry is unnecessary and not advised (1).

Screening spirometry in the general population for COPD is controversial. It’s likely not indicated in asymptomatic individuals without significant risk factors. However, in symptomatic individuals or those with risk factors (e.g., >20 pack-years smoking, recurrent infections, prematurity), spirometry is valuable for case finding (1). Targeted case finding strategies based on risk factors and symptoms are crucial for early COPD diagnosis as per health care guidelines.

Terminology in COPD: Clarifying Stages and Types

GOLD 2023 clarifies COPD terminology to reflect the understanding of varying lung function trajectories and disease development pathways. Consistent terminology is essential for clear communication and research in COPD health care guidelines.

Early COPD

“Early COPD” is best used in experimental settings to describe biological first steps of disease development. Clinically, identifying “early” COPD is challenging, and the term should be used cautiously in patient communication.

Mild COPD

“Mild” should only describe spirometrically measured airflow obstruction severity (GOLD grade 1). It should not be used as a surrogate for “early” disease, as mild airflow obstruction can occur at any age and doesn’t always represent early-stage disease. Severity classification should be distinct from disease stage in health care guidelines and patient communication.

Young COPD

“Young COPD” refers to patients aged 20-50 years (63), recognizing that COPD can manifest early in life due to abnormal lung development or accelerated decline (64, 65). COPD in younger individuals can have significant health impacts (65, 66. Family history and early-life events are often relevant in young COPD patients (65). Recognizing young COPD as a distinct category can guide targeted research and management strategies within health care guidelines.

Pre-COPD

“Pre-COPD” describes individuals with respiratory symptoms and/or structural/functional abnormalities (e.g., emphysema, hyperinflation, rapid FEV1 decline) but without airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC > 0.7) (67). These individuals are already considered “patients” due to symptoms or abnormalities and may or may not develop COPD over time (67. There’s a lack of evidence on optimal treatment for pre-COPD (68, highlighting a need for research in this area, including RCTs in pre-COPD and young COPD populations (69). Early intervention strategies for pre-COPD are an emerging area in health care guidelines.

PRISm

“PRISm” (Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry) describes individuals with FEV1/FVC ≥0.7 and FEV1 <80% predicted (70, 71). PRISm prevalence is notable, especially in smokers, and is associated with increased mortality (71. PRISm can transition to different spirometric patterns over time (71. Pathogenesis and treatment of PRISm require further investigation. Recognizing PRISm as a distinct category can improve risk stratification and guide future research within health care guidelines.

Taxonomy of COPD: Etiotypes

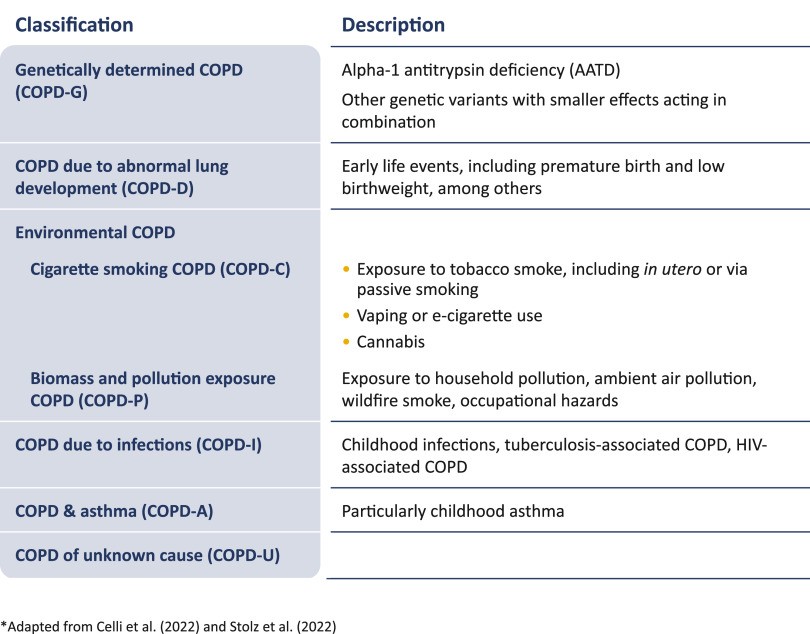

GOLD 2023 proposes a new COPD taxonomy based on different causes or “etiotypes” (Figure 1), emphasizing non-smoking related COPD and stimulating research into mechanisms, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment for these prevalent COPD forms (13, 72). Etiotype-based taxonomy can personalize COPD management and research directions within health care guidelines.

Figure 1.

Proposed taxonomy (etiotypes) for COPD. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Reprinted with permission of www.goldcopd.org from Reference 1.

Clinical Presentation of COPD

COPD patients may present with dyspnea, wheezing, chest tightness, fatigue, activity limitation, cough (with or without sputum), and acute respiratory exacerbations requiring specific management. Comorbidities are frequent and significantly impact clinical presentation and prognosis (73, independent of airflow obstruction severity. Comprehensive assessment of symptoms, exacerbation history, and comorbidities is crucial in COPD health care guidelines.

Assessment of COPD: ABE Tool and Imaging

Initial COPD assessment, guided by health care guidelines, aims to determine airflow limitation severity (GOLD grades), symptom nature and magnitude, exacerbation history (future risk indicator), and presence of comorbidities.

Combined Initial COPD Assessment: From ABCD to ABE

GOLD 2023 updates the ABCD assessment tool to ABE (Figure 2), emphasizing exacerbation risk independently of symptom level (75. Symptom and exacerbation history thresholds remain unchanged. Former C and D groups are merged into Group E (“Exacerbations”). This shift impacts initial pharmacological treatment recommendations, prioritizing exacerbation risk in management decisions as per health care guidelines. Clinical validation of the ABE tool’s practical value is ongoing.

Figure 2.

GOLD ABE assessment tool. Exacerbation history refers to exacerbations experienced the previous year. CAT = COPD Assessment Test; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; mMRC = modified Medical Research Dyspnea Questionnaire. Reprinted with permission of www.goldcopd.org from Reference 1.

Imaging in COPD

Chest X-ray cannot confirm COPD diagnosis but can reveal signs like hyperinflation and exclude other diagnoses or comorbidities (fibrosis, bronchiectasis, pleural disease, cardiomegaly).

Chest CT provides valuable information:

- Emphysema presence, severity, and distribution, relevant for lung volume reduction and associated with faster FEV1 decline, mortality, and lung cancer risk (76).

- Bronchiectasis, present in ~30% of COPD patients, linked to increased exacerbations and mortality (77).

- Lung cancer screening eligibility; most COPD patients meet screening criteria (78, 79).

- Airway abnormalities quantification (less standardized) (80–82).

- Comorbidities (coronary calcifications, pulmonary artery enlargement, bone density, muscle mass) impacting mortality (83).

GOLD 2023 recommends chest CT for COPD patients with persistent exacerbations, disproportionate symptoms, severe airflow obstruction with hyperinflation, or lung cancer screening criteria. Imaging is an important adjunct to spirometry in COPD assessment within health care guidelines.

Pharmacological Treatment of COPD

Pharmacological therapy must always be combined with non-pharmacological measures, including smoking cessation. Inhaled therapy is the cornerstone of COPD management, and proper inhaler device use is critical. Patient and provider education on device technique and regular follow-up assessments are essential components of health care guidelines. Device choice should consider availability, patient preference, and inhalation ability (84).

Initial Pharmacological Treatment

GOLD 2023 recommendations for initial pharmacological therapy are shown in Figure 3. Group A treatment remains unchanged. For Group B, dual LABA+LAMA bronchodilator therapy is now recommended as initial therapy, being more effective than monotherapy with similar side effects (85–87). For Group E, LABA+LAMA is also the initial recommendation, with consideration of triple therapy (LABA+LAMA+ICS) for patients with blood eosinophils ≥300 cells/μl. LABA+ICS monotherapy is discouraged; if ICS is indicated, LABA+LAMA+ICS is preferred (88, 89). COPD patients with concomitant asthma should be treated as asthma (90). These updated initial treatment recommendations reflect a shift toward dual bronchodilation and eosinophil-guided ICS use within health care guidelines.

Figure 3.

Initial pharmacological treatment. CAT = COPD Assessment Test; eos = eosinophils; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β2 adrenergic receptor agonist; LAMA = long-acting antimuscarinic agonist; mMRC = modified Medical Research Dyspnea Questionnaire. Reprinted with permission of www.goldcopd.org from Reference 1.

Follow-Up Pharmacological Treatment

Follow-up treatment should be guided by “review and assess,” then “adjust” principles, based on treatable traits (TTs) (91): dyspnea and exacerbations (Figure 4). TTs are identified clinically (phenotypes) or through biomarkers (endotypes, e.g., eosinophils for ICS) (91. TTs can coexist and change over time (92). Follow-up treatment recommendations largely align with previous guidelines but no longer include LABA+ICS alone. Personalized, treatable-trait based approaches are emphasized in COPD health care guidelines.

Figure 4.

Follow-up pharmacological treatment. For definition of abbreviations, see Figure 3. Reprinted with permission of www.goldcopd.org from Reference 1.

For persistent dyspnea on bronchodilator monotherapy, step up to LABA+LAMA. If symptoms persist, consider inhaler device/molecule switch or investigate other dyspnea causes.

For persistent exacerbations on bronchodilator monotherapy, escalate to LABA+LAMA, except for patients with eosinophils ≥300 cells/μl, who may escalate to LABA+LAMA+ICS. For exacerbations on LABA+LAMA, escalate to LABA+LAMA+ICS if eosinophils ≥100 cells/μl. For persistent exacerbations despite LABA+LAMA+ICS or eosinophils <100 cells/μl, consider roflumilast (93–95 or macrolides (especially in non-smokers) (96, 97.

Closely monitor patients after treatment modifications. Treatment escalation is not systematically tested, and de-escalation trials mainly focus on ICS withdrawal (98. ICS de-escalation may be considered if pneumonia or side effects occur. Eosinophil count ≥300 cells/μl increases exacerbation risk with ICS withdrawal. Patients well-controlled on LABA+ICS (without asthma features) may continue it, but consider switching to LABA+LAMA for dyspnea or escalating to LABA+LAMA+ICS for exacerbations. Step-up and step-down approaches based on symptoms, exacerbations, and eosinophil levels are integral to follow-up COPD health care guidelines.

Other Therapeutic Considerations

Eosinophils as a biomarker: Eosinophil count and exacerbation history guide ICS initiation (Figure 5) (88, 89, 99–102). ICS benefit is minimal at eosinophils <100 cells/μl (103, 104. Benefit is graded between 100-300 cells/μl (103, 104. Historical eosinophil counts are reasonably repeatable for treatment decisions (105, though variability increases at higher thresholds (106. Eosinophil-guided therapy optimizes ICS use in COPD health care guidelines.

Figure 5.

Factors to consider when adding treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) to long-acting bronchodilators (note that the scenario is different when considering ICS withdrawal). COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Reprinted with permission of www.goldcopd.org from Reference 1.

Chronic bronchitis (CB), defined by chronic cough and sputum, affects 27-35% of COPD patients, associated with worse outcomes. Treatment is challenging but includes smoking cessation, LAMA, mucolytics, antioxidants, and oscillating positive expiratory pressure. Inhaled mucolytics and DNase are not recommended (1). Newer therapies like cryospray, rheoplasty, and targeted lung denervation are under evaluation. Managing chronic bronchitis symptoms is a key aspect of COPD health care guidelines.

Affordability of inhaled medicines is a major concern in LMICs, requiring urgent attention to ensure universal access to essential COPD therapies. Even in developed countries, branded inhalers pose cost barriers. Addressing medication affordability is a global health equity issue within COPD health care guidelines.

Reducing lung function decline and mortality is a primary goal of COPD management. While pharmacotherapy may slow lung function decline in some patients, more research is needed to identify responders (1). Several interventions, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological (Figure 6), reduce mortality in selected COPD patients. Targeted case finding, patient characterization, and individualized therapy are essential to implement these mortality-reducing strategies as per health care guidelines.

Figure 6.

Evidence supporting a reduction in mortality with pharmacotherapy and nonpharmacotherapy in patients with COPD. Superscript numerals are reference citations as follows: 1 (89, 192), 2 (193), 3 (156, 157, 194), 4 (195, 196), 5 (197), and 6 (198). CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ETHOS = Efficacy and Safety of Triple Therapy in Obstructive Lung Disease; HR = hazard ratio; IMPACT = Informing the Pathway of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Treatment; MRC = Medical Research Council; NOTT = Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial; RCT = randomized clinical trial; RR = risk ratio. Reprinted with permission of www.goldcopd.org from Reference 1.

Nonpharmacological Therapy in COPD

Nonpharmacological treatment is a crucial component of comprehensive COPD management, as emphasized in health care guidelines.

Education

All COPD patients should receive education on COPD, medications, inhaler devices, dyspnea management strategies, and when to seek help. Patient education empowers self-management and improves adherence to health care guidelines.

Smoking Cessation

Approximately 40% of COPD patients continue smoking, negatively impacting prognosis (108). All smokers should be offered smoking cessation support and treatment. Smoking cessation is the most impactful non-pharmacological intervention in COPD health care guidelines.

Vaccination

Influenza, pneumococcus, COVID-19, pertussis, and herpes zoster vaccinations should be offered according to local guidelines (1). Vaccination reduces respiratory infection risk and exacerbations, a key preventive measure in COPD health care guidelines.

Physical Activity

Physical activity is reduced in COPD (109. All patients should be encouraged to remain active (110, 111. Technology-based interventions can enhance exercise self-efficacy and promote lifestyle changes (112. Promoting physical activity is essential for improving functional status and quality of life in COPD health care guidelines.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), including community and home-based programs, is beneficial (1). Patients with high symptom burden and exacerbation risk (GOLD groups B and E) should be referred to formal PR programs (113–116. Tele-rehabilitation is a viable alternative, especially post-pandemic, with similar benefits to center-based PR (117. Optimal delivery, content, and duration of tele-rehabilitation are still being established (118, 119. PR is a cornerstone of non-pharmacological COPD management within health care guidelines.

Oxygen Therapy and Ventilatory Support

Criteria for long-term oxygen therapy and ventilatory support remain unchanged and are detailed in the GOLD 2023 report (1). These therapies are reserved for specific indications in advanced COPD as per health care guidelines.

Surgical and Endoscopic Lung Volume Reduction

In select patients with severe emphysema refractory to medical management, surgical or bronchoscopic lung volume reduction may be considered (Figure 7). Bullectomy is an option for large bullae, and lung transplantation for very severe COPD without contraindications. These interventions are advanced options for carefully selected patients within COPD health care guidelines.

Figure 7.

Surgical and interventional therapies in advanced emphysema. Homogeneous emphysema was defined as a www.goldcopd.org from Reference 1.

End-of-Life and Palliative Care

All patients with advanced COPD should be considered for palliative care to optimize symptom control and facilitate informed decision-making for patients and families. Palliative care is an essential aspect of comprehensive COPD health care guidelines, particularly in advanced stages.

Exacerbations of COPD (ECOPD)

ECOPD negatively impact health status, disease progression, and prognosis (120.

New Definition of ECOPD

GOLD 2023 adopts the Rome consensus definition (120) to address limitations of the previous non-specific definition. ECOPD is now defined as: “an event characterized by dyspnea and/or cough and sputum that worsen over ≤14 days, which may be accompanied by tachypnea and/or tachycardia and is often associated with increased local and systemic inflammation caused by airway infection, pollution, or other insult to the airways.” This refined definition improves clarity and clinical relevance for managing exacerbations within health care guidelines.

Differential Diagnosis of ECOPD

COPD patients are at increased risk for acute events mimicking or aggravating ECOPD, such as heart failure, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolism (Figure 8) (121). Worsening dyspnea, especially with cough and purulent sputum, may suggest ECOPD. However, atypical presentations, particularly dyspnea without classic ECOPD features, warrant consideration of alternative diagnoses (121). Differential diagnosis is crucial for accurate ECOPD management within health care guidelines.

Figure 8.

Classification of the severity of COPD exacerbations. ABG should show new-onset/worsening hypercapnia or acidosis, as a few patients may have chronic hypercapnia. Adapted from Reference 120. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECOPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Reprinted with permission of www.goldcopd.org from Reference 1.

Assessment of ECOPD Severity

The Rome proposal suggests using easily obtainable clinical variables to define ECOPD severity (mild, moderate, severe) at the point of care (Figure 8) (120). In primary care, assess dyspnea intensity (VAS 0-10), respiratory rate, heart rate, and oxygen saturation. CRP measurement is recommended when available. Arterial blood gases are needed to assess ventilatory support needs, typically in emergency or hospital settings. Moving from mild to moderate severity requires exceeding thresholds in at least three variables. Prospective validation is hoped to refine exacerbation definition and severity assessment, and to identify more specific biomarkers than CRP for lung injury in ECOPD within health care guidelines.

Management of ECOPD

ECOPD management setting (outpatient vs. inpatient) depends on exacerbation severity, underlying COPD, and comorbidities.

Hospitalization indications:

- Severe symptoms (worsening dyspnea, high respiratory rate, desaturation, confusion).

- Acute respiratory failure.

- New physical signs (cyanosis, edema).

- Failure to respond to outpatient management.

- Serious comorbidities (heart failure, arrhythmias).

- Insufficient home support (1).

In the emergency department, hypoxemic patients need supplemental oxygen and assessment for noninvasive ventilation if increased work of breathing or impaired gas exchange is present. Less severe cases can be managed in the emergency department or hospital ward.

Pharmacological Treatment of ECOPD

Bronchodilators: Short-acting beta-agonists (SABA) with or without short-acting anticholinergics (SAMA) are initial bronchodilators, via MDI with spacer or nebulization (1). Air-driven nebulizers are preferred over oxygen-driven to avoid hypercapnia risk (123. Continue long-acting bronchodilators during exacerbation or start them pre-discharge (1). Intravenous methylxanthines are not recommended due to limited efficacy and side effects (124, 125. Bronchodilator therapy is central to acute ECOPD management within health care guidelines.

Glucocorticoids: Systemic glucocorticoids improve lung function, oxygenation, reduce relapse, treatment failures, and hospitalization length in ECOPD (126–128. 40 mg prednisone-equivalent daily for 5 days is recommended (129. Longer courses increase pneumonia and mortality risk (130. Oral prednisolone is as effective as IV (131. Nebulized budesonide is an alternative in some patients (127, 132. Glucocorticoids may be less effective in patients with low eosinophils (133. Systemic corticosteroids are a cornerstone of moderate-to-severe ECOPD management within health care guidelines.

Antibiotics: Antibiotics are indicated for ECOPD with increased sputum volume and purulence, and in most patients needing mechanical ventilation (134. Recommended duration is 5-7 days (135. Choice depends on local resistance patterns. Empirical treatment often includes aminopenicillin with clavulanate, macrolides, tetracycline, or quinolones. In patients with frequent exacerbations, severe airflow obstruction, or ventilation needs, sputum cultures are recommended to guide therapy against potential gram-negative bacteria or resistant pathogens. Administration route (oral or IV) depends on patient factors and antibiotic pharmacokinetics. Antibiotic use in ECOPD should be judicious and guided by clinical and microbiological factors within health care guidelines.

Adjunct therapies: Fluid balance, comorbidity management, and nutritional support are important. Thromboprophylaxis should be considered in hospitalized ECOPD patients (136, 137. Reinforce smoking cessation. Supportive care and comorbidity management are integral to comprehensive ECOPD management within health care guidelines.

Oxygen therapy: Titrate supplemental oxygen to a target saturation of 88-92% (138. Monitor blood gases for CO2 retention and acidosis. Pulse oximetry may overestimate oxygen saturation in darker skin tones (140. Venturi masks offer more accurate oxygen delivery than nasal prongs (1). Oxygen therapy is crucial for hypoxemic ECOPD patients within health care guidelines.

High-flow nasal therapy (HFNT) may improve respiratory rate, lung mechanics, and gas exchange in hypercapnic ECOPD (142–144 but doesn’t prevent intubation (145. ERS recommends ventilatory support before HFNT in hypercapnic ECOPD (146. HFNT may have a role in select ECOPD patients, but ventilatory support is prioritized in hypercapnia within health care guidelines.

Ventilatory support: Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is preferred as initial mode (147, 148, improving gas exchange, respiratory rate, work of breathing, breathlessness, and reducing intubation, complications, length of stay, and mortality (147, 148. NIV can be discontinued directly after improvement and tolerance of unassisted breathing (149. Invasive ventilation is rescue therapy for NIV failure (150, influenced by reversibility, patient wishes, and ICU availability. Advance directives are helpful in decision-making. Risks include ventilator-acquired pneumonia and barotrauma. Respiratory stimulants are not recommended (1. Early NIV use is prioritized in severe ECOPD with respiratory failure within health care guidelines.

Hospital Discharge, Readmissions, and Follow-Up after ECOPD

Hospital discharge timing lacks standardization. Early readmissions are frequent. Risk factors for 30- and 90-day readmission include comorbidities, prior exacerbations/hospitalizations, and longer hospital stays (151. Pre-discharge education on medications, home support, and follow-up plans are crucial (152. Early follow-up (within one month) is linked to fewer readmissions (153. 3-month follow-up is recommended to assess stable state, symptoms, lung function, and prognosis (e.g., BODE index) (154. Arterial oxygen saturation and blood gases at follow-up guide long-term oxygen therapy needs (155. Pulmonary rehabilitation initiation within 4 weeks post-discharge has unclear effects (156, 157. Structured discharge planning and early follow-up are key to reducing readmissions and improving outcomes post-ECOPD within health care guidelines.

Prognosis Post-ECOPD

Long-term prognosis after ECOPD hospitalization is poor, with ~50% 5-year mortality (158). Poor prognostic factors include older age, low BMI, comorbidities, prior exacerbations, index exacerbation severity, and need for long-term oxygen therapy at discharge (159–161. Risk stratification and targeted interventions are needed to improve long-term outcomes post-ECOPD within health care guidelines.

Comorbidities, Multimorbidity, and Frailty in COPD

COPD commonly coexists with other diseases (162 that significantly impact clinical course and prognosis. Comorbidities can mimic COPD symptoms, complicate diagnosis, and limit pulmonary reserve. COPD can worsen outcomes of other conditions. Some comorbidities share risk factors with COPD or are causally linked (163. Comorbidity management is integral to holistic COPD health care guidelines.

Generally, comorbidity presence should not alter COPD treatment, and comorbidities should be managed per standard guidelines, independent of COPD. Simplify treatment and minimize polypharmacy. Integrated management of COPD and comorbidities is key for optimal patient care within health care guidelines.

Cardiovascular Diseases and COPD

Cardiovascular diseases are common in COPD (20-70% prevalence) (164, including heart failure, ischemic heart disease, arrhythmias, peripheral vascular disease, and hypertension. Manage cardiovascular conditions per established guidelines, including selective β1-blockers when indicated, regardless of COPD diagnosis.

Lung Cancer and COPD

Lung cancer is frequent in COPD (165. Annual low-dose CT lung cancer screening is recommended for COPD patients who smoke (78, 79. Screening benefit in non-smoking COPD is less established.

Bronchiectasis and COPD

Bronchiectasis affects ~30% of COPD patients (166, associated with increased sputum, infections, and exacerbations. Chest CT is recommended if bronchiectasis is suspected.

Sleep Apnea and COPD

Sleep apnea occurs in ~14% of COPD patients (167, worsening prognosis due to increased desaturation and hypoxemia.

Osteoporosis and COPD

Osteoporosis is underdiagnosed in COPD (168, linked to poor health status and prognosis. Minimize systemic corticosteroid use to reduce osteoporosis risk.

Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, and COPD

Diabetes is more frequent in COPD and may worsen prognosis (164. Metabolic syndrome prevalence is >30% in COPD (169. Manage diabetes and metabolic syndrome per standard guidelines.

Gastroesophageal Reflux (GERD) and COPD

GERD is an independent exacerbation risk factor and linked to worse health status in COPD (170, 171. Proton pump inhibitors for GERD in COPD are controversial regarding exacerbation prevention (172, 173. Optimal GERD management in COPD is unclear.

Anemia and COPD

Anemia is frequent in COPD (174, associated with older age, comorbidities, dyspnea, worse quality of life, airflow obstruction, reduced exercise capacity, and increased exacerbation and mortality risk.

Secondary Polycythemia and COPD

Secondary polycythemia in COPD may be linked to pulmonary hypertension (175, 176, venous thromboembolism (176, and mortality. Prevalence has decreased with long-term oxygen therapy (177.

Mental Health and COPD

Anxiety and depression are common, underdiagnosed COPD comorbidities (179–182, associated with poor prognosis (181, 183. Cognitive impairment occurs in a significant proportion of COPD patients (185, 186. Mental health assessment and management are crucial in COPD health care guidelines.

Multimorbidity, Frailty, and COPD

Multimorbidity (≥2 chronic conditions) and frailty (weakness, fatigue, low activity, weight loss) are increasingly prevalent in aging COPD patients (187. Multimorbidity and frailty complicate COPD management and worsen prognosis, requiring comprehensive geriatric assessment and tailored care within health care guidelines.

COPD and COVID-19

COPD patients should adhere to infection control measures for SARS-CoV-2 prevention (188, including social distancing and handwashing, and receive COVID-19 vaccination per guidelines. Facial coverings may be advisable during high community transmission periods (1). Continue usual COPD medications during the pandemic (189.

Exacerbation and hospitalization rates decreased during early pandemic phases (190, possibly due to infection control measures. Maintain social connection and physical activity despite distancing. Ensure medication supplies.

COPD patients may not have increased SARS-CoV-2 infection risk, possibly due to protective measures (189, but have higher hospitalization, ICU admission, and mortality risk if infected (191. Test COPD patients with new or worsening respiratory symptoms for SARS-CoV-2, even if mild. COVID-19 considerations are an evolving aspect of COPD health care guidelines.

New Opportunities in COPD Management

COPD is common, preventable, and treatable, yet underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis are widespread (1. Recognizing non-smoking COPD causes, early-life onset, and precursor conditions (“Pre-COPD,” “PRISm”) offers new avenues for prevention, early diagnosis, and timely intervention (72. Mortality reduction is achievable with available therapies (Figure 6, but diagnosis is essential for implementation. Reinforce strategies to address COPD underdiagnosis for improved health outcomes and effective health care guidelines implementation.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Katie Langefeld and Ruth Hadfield for editing, and the GOLD Emeriti Academy, GOLD Assembly, and industry stakeholders for feedback on the 2023 GOLD report.

Footnotes

These recommendations are from GOLD and not official American Thoracic Society guidelines. They have not been reviewed or endorsed by the ATS Board of Directors.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202301-0106PP on March 1, 2023

Author disclosures are available at www.atsjournals.org.

References

[1] Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2023 report. www.goldcopd.org Accessed March 1, 2023.

[2] Agusti A, Fabbri LM, Singh D, Vestbo J, Celli BR, Franssen FME, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Criner GJ, Barnes PJ, Locantore N, et al. Precision medicine in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 Jul;9(7):755-764. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00059-1. PubMed

[3] Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ, Nishimura M, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Feb 15;187(4):347-65. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. PubMed

[4] Guerra S, Stern DA, Zhou M, Anderson-Berry A, Castro Rodriguez JA, Dimich-Ward H, Engle L, Esteban-Cruciani N, Graham BL, Kechris K, et al. GETomics: gene-environment-time interactions in asthma and COPD across the lifespan. Thorax. 2022 Feb;77(2):194-201. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216599. PubMed

[5] Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. Br Med J. 1977 Jun 18;1(6077):1645-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. PubMed

[6] Burgel PR, Bhatt SP, Criner GJ, Agusti A, Price D, Martinez FJ, Yates J, Fan VS, Lomas DA, Singh D, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force on COPD Phenotypes. COPD Exacerbations Phenotypes: A Framework for Clinical Trials and Personalized Medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Mar 1;201(5):529-536. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1639PP. PubMed

[7] Lamprecht F, Stocks J, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Tan WC, Cerveri I, Martinez-Larrarte P, Mannino DM, Bateman ED, Reddihough DP, et al. COPD in never smokers: results from the population-based burden of obstructive lung disease study. Chest. 2011 Dec;140(6):1385-93. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0335. PubMed

[8] Eisner MD, Anthonisen N, Coultas D, et al. An official American Thoracic Society public policy statement: novel tobacco products: electronic cigarettes, hookah, and smokeless tobacco. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Nov 15;182(9):1169-76. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201007-1091PP. PubMed

[9] van der Deen FS, Willemse BW, Ten Hacken NH, Postma DS, Timens W, Hiemstra PS, van den Berge M. Systemic inflammation and remodeling in the airways and lung parenchyma of smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Oct 15;184(8):917-23. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0516OC. PubMed

[10] Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Gorelick DA, Gevorkyan H, Gan WQ, Kleerup EC, Colletti P, Sylvester M, Sze DY, Grigoryan L, et al. Chronic effects of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997 Feb;155(2):491-9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9034174. PubMed

[11] O’Donnell DE, Aaron SD, Bourbeau J, Hernandez P, Marciniuk DD, Balter M, Ford G, Maltais F, Ramirez R, Science Committee of the Canadian Thoracic Society. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease–2008 update–highlights for primary care. Can Respir J. 2008 Jul-Aug;15(4):17A-24A. doi: 10.1155/2008/924385. PubMed

[12] Gilliland FD, Berhane K, Li YF, Gauderman WJ, McConnell R, Islam T, Peters JM. Effects of early onset transient wheezing, parental smoking, and feline pet exposure on childhood lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Feb 15;167(4):408-13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-569OC. PubMed

[13] Salvi SS, Agarwal A. COPD in never-smokers. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2022 Oct 27;9(4):510-523. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.2022.0342. PubMed

[14] Kurmi OP, Sadhra S, Sadhra SS, Simkhada P, Steiner MF, Dhakal S, Lam KB, Devereux G, Semple S, Ayres JG. Effect of exposure to biomass smoke on respiratory symptoms and lung function in adult rural population of Nepal. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052798. PubMed

[15] Hu G, Semple S, Jalaludin B, Young RP, FitzPatrick M, Abramson MJ, Sim MR, Dennekamp M. Household air pollution and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2010 Oct;65(10):876-85. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.129659. PubMed

[16] Mortimer K, Crichton J, Naidoo R, et al. Impact of household air pollution interventions on chronic respiratory illness in low and middle income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2017 Dec;72(12):1071-1080. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209774. PubMed

[17] Singh D, McCall F, Jethwa H, et al. Macrophage phagocytosis of bacteria is impaired in COPD patients who are nonsmokers. Eur Respir J. 2018 Aug;52(2):1800684. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00684-2018. PubMed

[18] Blanc PD, Annesi-Maesano I, Balmes JR, Cummings KJ, Fishwick D, Miedinger D, Paulin LM, Pin I, Sigsgaard T, Toren K, et al. The occupational burden of nonasthmatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Nov 15;176(10):945-55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1842PP. PubMed

[19] Hnizdo E, Sullivan PA, Bang KM, Wagner GR. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and employment by industry and occupation in the US population: a study of data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2002 Jul 15;156(2):138-46. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf034. PubMed

[20] Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Yelin EH, Katz PP, Earnest G, Henneberger PK, Woodruff TJ. Occupation and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a population-based sample: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Thorax. 2001 Feb;56(2):93-8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.2.93. PubMed

[21] Gan WQ, Man SF, Su Z, et al. Association between chronic exposure to fine particulate matter and lung function decline in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Apr 1;197(7):857-865. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1623OC. PubMed

[22] Chen H, Kwong JC, Copes R, Tu JV, Villeneuve PJ, van Donkelaar A, Hystad P, Martin RV, Brook JR, Weichenthal S. Living near major roads and the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort study. Environ Health Perspect. 2017 Aug 18;125(8):087013. doi: 10.1289/EHP1249. PubMed

[23] Miller MR, якось далі Raaschou-Nielsen O, Anderson HR, Atkinson R, Kelly FJ, Künzli N, Langrish JP,