Introduction

In the intricate world of healthcare, understanding how hospitals categorize and manage patient care is crucial. Diagnosis-Related Groups, or DRGs, are a classification system developed to standardize the way hospitals are reimbursed and to provide a framework for understanding hospital resource utilization. Initially designed to focus on the resources consumed during a hospital stay, DRGs have evolved into a powerful tool for analyzing and improving healthcare delivery. But What Are Diagnosis-related Groups And Why Should You Care? This article delves into the concept of DRGs, their significance, and why they matter to healthcare professionals, policymakers, and even patients.

The DRG system was initially conceived as a method to categorize hospitalized patients into groups with similar clinical processes and predictable service needs. This classification, primarily based on the length of hospital stay – a strong indicator of case complexity and cost – aimed to help manage the discretionary elements within hospital expenditures. The idea was that by standardizing categories, inefficiencies and variations in resource use could be identified and addressed.

However, focusing solely on the length of stay overlooks another critical factor influencing overall healthcare costs: the frequency of hospital admissions. For many diagnostic categories, the admission rate is a more significant determinant of patient days of care than the duration of the hospital stay itself. This highlights the importance of understanding the factors that drive hospital admission decisions, particularly the role of professional discretion.

Studies on small-area variations have revealed considerable differences in hospital admission rates for the same conditions across different geographic areas. These variations often stem from “discretionary decisions” – choices made by physicians when the best course of treatment isn’t definitively established by research, leading to differing opinions among medical professionals about the necessity of hospitalization.

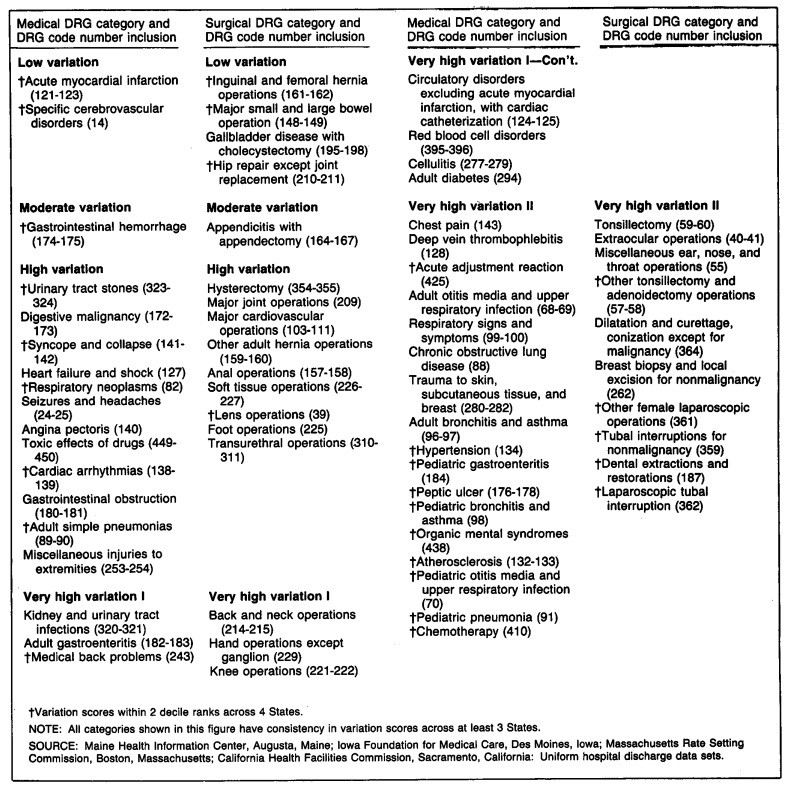

This article explores how variations in hospital admission rates can be used to classify DRG categories based on the Index of Discretionary Admissions. By examining consistent patterns of variation across different states, we can gain valuable insights into the discretionary component of hospital admissions and its implications for healthcare quality and cost-effectiveness. Understanding what are diagnosis-related groups and why should you care starts with recognizing their role in revealing these crucial variations in healthcare practices.

Understanding Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs)

Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs) are essentially a patient classification system that groups together individuals with similar diagnoses, treatments, and resource consumption patterns during a hospital stay. Think of them as standardized categories that help to make sense of the vast diversity of patients and conditions treated in hospitals.

The development of DRGs in the 1980s was a response to the need for a more structured and clinically meaningful way to categorize hospital cases. Prior to DRGs, hospital reimbursement systems often lacked standardization, leading to inefficiencies and difficulties in comparing hospital performance. The DRG system aimed to address these issues by creating categories that were:

- Clinically Coherent: Grouping patients with similar medical conditions and treatment pathways.

- Resource Homogeneous: Reflecting similar levels of resource consumption, such as length of stay and services utilized.

Alt text: Figure 1. Modified diagnosis-related group (DRG) categories classified by medical or surgical and degree of hospitalization rate variation, providing a visual representation of DRG categorization.

The primary criterion initially used for grouping patients into DRGs was the length of stay. Length of stay is a readily available and reliable data point that correlates with the complexity of the case and the total hospital charges. While physician input was considered to ensure clinical relevance, the emphasis on length of stay reflected its practical importance in hospital management and reimbursement.

DRGs are not just about classifying patients for payment purposes. They also serve as a valuable tool for:

- Hospital Management: DRGs help hospitals understand their case mix, resource utilization patterns, and identify areas for potential efficiency improvements.

- Quality Improvement: By analyzing outcomes and variations within specific DRGs, hospitals can identify best practices and areas where patient care can be enhanced.

- Healthcare Policy: DRGs provide a standardized framework for comparing hospital performance, analyzing healthcare costs, and developing payment policies.

Understanding what are diagnosis-related groups and why should you care is fundamental to grasping how healthcare systems manage and evaluate hospital services. DRGs provide a common language and structure for discussing and addressing key issues in healthcare delivery.

The Concept of Discretionary Admissions and Variation

While DRGs provide a standardized framework for classifying hospital cases, the decision of when to admit a patient to the hospital can be subject to considerable variation. This is where the concept of “discretionary admissions” comes into play. Discretionary admissions refer to hospitalizations where the necessity of admission is not clear-cut, and professional judgment plays a significant role.

These discretionary decisions arise when:

- Clinical Evidence is Inconclusive: Outcome studies may not definitively favor one treatment approach over another, leading to uncertainty about the optimal course of care.

- Physician Disagreement Exists: Medical professionals may hold differing opinions on the most appropriate treatment setting (inpatient vs. outpatient) for certain conditions.

The significance of discretionary admissions is highlighted by studies showing substantial geographic variation in hospital admission rates for certain conditions. This variation is not typically explained by differences in patient populations’ health needs or demographic factors like income or insurance coverage. Instead, it often reflects variations in physician practice styles and the degree of professional discretion exercised in admission decisions.

Conditions with high levels of discretionary admission often include procedures where:

- Outpatient Alternatives Exist: Many procedures can be performed safely and effectively in outpatient settings, but practice patterns may vary, with some physicians or hospitals preferring inpatient admission.

- Treatment Benefit is Debated: For some conditions, the medical literature may contain ongoing discussions and controversies regarding the value and effectiveness of certain treatments, leading to variations in treatment approaches and hospitalization decisions.

In contrast, conditions with low variation in admission rates tend to be those where:

- Hospitalization is Clearly Mandated: Conditions like myocardial infarction (heart attack) or inguinal hernia repair generally require hospital-based care according to established medical standards.

- Strong Professional Consensus Exists: There is broad agreement among medical professionals on the necessity of acute hospitalization for these conditions.

Alt text: Figure 2. Hospitalization rates for varied medical diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) and surgical procedures, categorized by degree of variation, illustrating the range of admission rates in different market areas.

Understanding the concept of discretionary admissions is crucial for anyone seeking to understand what are diagnosis-related groups and why should you care. It reveals that DRGs are not just static categories, but they are also influenced by dynamic factors like professional judgment and variations in medical practice, which have significant implications for healthcare resource utilization and costs.

Measuring Variation: The Systematic Component of Variation (SCV)

To effectively study and classify DRGs based on the degree of discretionary admissions, a robust method for measuring variation in hospitalization rates is essential. The Systematic Component of Variation (SCV) is a statistical measure specifically designed for this purpose.

The SCV was developed to address the limitations of simpler variation measures, such as the coefficient of variation or chi-square statistics, which can be influenced by factors like the size of the population being studied or the overall rate of hospitalization. The SCV, in contrast, aims to isolate the “systematic” variation – the portion of variation that is not due to random chance.

Here’s how the SCV works in principle:

- Acknowledging Random Variation: The SCV recognizes that some variation in hospitalization rates across different geographic areas will occur simply due to random fluctuations, especially in smaller populations or for less common conditions.

- Identifying Systematic Variation: The SCV seeks to identify the variation that is systematic, meaning it is attributable to underlying factors that are not random. These systematic factors can include:

- Differences in Population Health: Although demographic factors are often adjusted for, subtle differences in the overall health status of populations in different areas could contribute to systematic variation.

- Variations in Physician Practice Styles: As discussed earlier, differences in professional judgment and treatment preferences are a major source of systematic variation in discretionary admissions.

- Availability of Healthcare Services: The supply of hospital beds or the accessibility of outpatient services in different regions can influence hospitalization rates.

The SCV is calculated using a statistical model (proportional hazards model) that separates the total observed variation into two components: random variation and systematic variation. By subtracting the estimated random variation from the total variance, the SCV provides a measure of the systematic variation.

Key advantages of using the SCV for analyzing DRG variation include:

- Independence from Rate Level: Unlike some other measures, the SCV is not strongly correlated with the average hospitalization rate for a given DRG. This allows for a fair comparison of variation across DRGs with different overall admission frequencies.

- Robustness: The SCV is relatively robust to variations in population size and other factors that can affect simpler variation measures.

By utilizing the SCV, researchers can more accurately assess the degree of systematic variation in hospitalization rates for different DRG categories. This, in turn, enables the classification of DRGs based on the extent of discretionary admissions, providing valuable insights into areas of healthcare where practice variations are most pronounced. Understanding what are diagnosis-related groups and why should you care becomes more meaningful when we can quantify and analyze the variations in their utilization using measures like the SCV.

Consistent Patterns of Variation Across States

A key finding in the research on DRGs and discretionary admissions is the remarkable consistency in patterns of variation across different geographic areas. Studies have examined hospitalization data from multiple states – including Iowa, California, Massachusetts, and Maine – and found that DRG categories tend to exhibit similar levels of variation in admission rates across these diverse regions.

To assess this consistency, researchers used the SCV to calculate a variation score for each DRG category within each state. Then, they ranked these scores and compared the rankings across states. Different criteria were used to define “consistency,” ranging from stricter criteria (variation scores within two deciles of each other across all states) to more lenient criteria (variation scores within three deciles in at least three out of four states).

The results revealed a high degree of consistency in variation patterns. Specifically:

- High Variation DRGs Consistently High: DRG categories identified as having high variation in one state tended to also show high variation in other states. Examples include procedures like laparoscopic tubal interruptions, tubal ligations for non-malignancies, and chemotherapy admissions.

- Low Variation DRGs Consistently Low: Conversely, DRG categories with low variation in one state, such as inguinal and femoral hernia repairs and acute myocardial infarction, also exhibited low variation in other states.

This consistency across geographically and demographically diverse states is significant because it suggests that the degree of variation in admission rates for specific DRG categories is not merely a local phenomenon but rather reflects something inherent in the nature of the medical conditions and treatments themselves. It implies that the level of discretion associated with hospital admission for certain conditions is relatively consistent, regardless of the specific healthcare system or population being studied.

Table 2 from the original study provides statistical evidence for this consistency, showing significant positive correlations in SCV scores and rankings of SCV scores between different states. These correlations, even between states as different as California and Iowa, underscore the robustness of the observed patterns of variation.

This finding has important implications for why you should care about diagnosis-related groups. The consistency of variation patterns strengthens the argument that discretionary admissions are a real and measurable phenomenon with broad implications for healthcare. It suggests that efforts to address unwarranted variations in healthcare practices can be targeted at specific DRG categories that consistently exhibit high levels of discretionary admission across different regions.

The Index of Discretionary Admissions and Its Implications

Building on the consistent patterns of variation observed across states, researchers developed the Index of Discretionary Admissions. This index classifies DRG categories into five levels based on their relative degree of variation in hospitalization rates, ranging from “low variation” to “very high variation II.”

The Index of Discretionary Admissions was created by:

- Calculating Mean Variation Scores: For each DRG category, a mean variation score was calculated using the SCV scores from the states with the most consistent decile ranks.

- Establishing Variation Levels: These mean variation scores were then used to categorize DRGs into five levels of discretionary admission:

- Low Variation: DRGs with variation scores similar to inguinal hernia repair.

- Moderate Variation: DRGs with variation scores ranging from appendectomy to hysterectomy.

- High Variation: DRGs with variation scores ranging from hysterectomy to back surgery.

- Very High Variation I: DRGs with variation scores ranging from back surgery to tonsillectomy.

- Very High Variation II: DRGs with variation scores as high as or higher than tonsillectomy.

Figure 1 visually represents this classification, showing how modified DRG categories are grouped by variation level.

The Index of Discretionary Admissions has several important implications for healthcare policy, research, and practice:

- Prioritizing Outcomes Research: DRG categories classified as “high” or “very high variation” should be prioritized for outcomes research. These are the areas where professional discretion is greatest, and where research is most needed to determine the optimal treatment approaches and reduce unwarranted practice variations.

- Guiding Utilization Review: The index can be used to guide utilization review efforts in hospitals and healthcare systems. By focusing on high-variation DRGs, reviewers can identify potential areas of overutilization or inappropriate hospital admissions.

- Informing Clinical Practice Guidelines: Understanding the discretionary levels associated with different DRGs can inform the development of clinical practice guidelines. Guidelines may be particularly valuable for high-variation DRGs, where clear recommendations can help reduce practice variations and improve patient care.

- Facilitating Hospital and Physician Performance Assessment: The index provides a framework for comparing hospital and physician practice styles regarding discretionary admissions. This information can be used for peer review, quality improvement initiatives, and efforts to promote evidence-based practice.

Table 4 from the original study demonstrates how hospitalizations in different states are distributed across these variation levels. It shows that a significant proportion of hospital admissions fall into the “high” and “very high variation” categories, highlighting the substantial scope for addressing discretionary admissions in healthcare.

Why Should You Care About DRGs and Discretionary Admissions?

So, why should you care about diagnosis-related groups and discretionary admissions? The answer lies in their profound impact on healthcare costs, quality, and the overall efficiency of the healthcare system.

For Healthcare Professionals:

- Understanding Practice Variation: DRGs and the concept of discretionary admissions shed light on the variations in medical practice that exist even for similar conditions. This awareness can encourage self-reflection and a commitment to evidence-based practice.

- Improving Patient Care: By focusing on high-variation DRGs, clinicians can identify areas where clinical uncertainty is greatest and where research and guideline development are most needed to optimize patient outcomes.

- Participating in Utilization Review and Quality Improvement: Understanding DRGs and discretionary admissions equips healthcare professionals to actively participate in utilization review and quality improvement initiatives aimed at reducing unwarranted variations and enhancing the value of care.

For Healthcare Policymakers and Administrators:

- Controlling Healthcare Costs: Discretionary admissions are a significant driver of healthcare costs. By understanding and addressing variations in admission practices for high-variation DRGs, policymakers and administrators can identify opportunities to improve efficiency and reduce unnecessary expenditures.

- Developing Value-Based Payment Models: DRGs form the basis for many value-based payment models. Understanding discretionary admissions is crucial for designing payment systems that incentivize high-quality, efficient care and discourage inappropriate hospitalizations.

- Prioritizing Research and Resource Allocation: The Index of Discretionary Admissions provides a valuable tool for prioritizing research funding and resource allocation. By focusing on high-variation DRGs, research efforts can be directed towards areas where the potential for improving patient care and reducing practice variation is greatest.

For Patients:

- Understanding Healthcare Decisions: While DRGs are primarily a tool for healthcare professionals, understanding the concept can empower patients to ask informed questions about their care. Knowing that admission decisions for certain conditions can be discretionary might encourage patients to discuss treatment options and the necessity of hospitalization with their doctors.

- Advocating for Evidence-Based Care: Ultimately, addressing discretionary admissions and practice variations is about ensuring that all patients receive the most effective and appropriate care, based on the best available evidence. Patients benefit from a healthcare system that is committed to reducing unwarranted variations and promoting high-quality, evidence-based practice.

In essence, understanding what are diagnosis-related groups and why should you care is about recognizing the complexities of healthcare delivery and the importance of continuous improvement. DRGs provide a framework for analyzing hospital care, and the concept of discretionary admissions highlights areas where professional judgment and practice variations play a significant role. By focusing on these areas, we can work towards a healthcare system that is more efficient, equitable, and delivers higher value to patients.

Limitations of DRGs and Future Directions

While DRGs are a valuable tool, it’s important to acknowledge their limitations and ongoing areas for development. The original research paper points out some key considerations:

- Surgical DRG Limitations: The DRG system, particularly for surgical procedures, may not always capture clinically meaningful distinctions. For example, the way DRGs are constructed can make it difficult to analyze specific procedures like prostatectomy. Alternative classification systems, like the Professional Activity Study classification, may offer better granularity for certain surgical analyses.

- Focus on Inpatient Setting: The initial DRG focus was primarily on inpatient hospitalizations. However, with the increasing shift towards outpatient care, it’s crucial to consider variations in both inpatient and outpatient settings to fully understand discretionary practices. Future research needs to incorporate data from ambulatory care settings to provide a more comprehensive picture.

- Need for Ongoing Refinement: The DRG system is not static and requires ongoing refinement. As medical knowledge and treatment practices evolve, DRG classifications need to be updated to remain clinically relevant and reflect current standards of care.

The original research also outlines future directions for research, including:

- Expanding Consistency Analysis: Analyzing variation patterns in additional states to further validate the consistency of discretionary admission levels across different regions.

- Grouping Residual Categories: Investigating and refining the classification of DRG categories that were initially excluded from the analysis (“residual categories”) to improve the comprehensiveness of the DRG system.

- Hospital-Specific Admission Patterns: Analyzing hospital-specific admission patterns using the Index of Discretionary Admissions to identify hospitals with markedly different admitting practices for high-variation DRGs. This could help target quality improvement efforts at the hospital level.

These future research directions underscore that understanding what are diagnosis-related groups and why should you care is an ongoing process. The DRG system is a dynamic tool that continues to evolve as healthcare research and practice advance. Addressing its limitations and pursuing further research will be crucial for maximizing the value of DRGs in improving healthcare delivery.

Conclusion

Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs) are more than just a reimbursement mechanism; they are a powerful framework for understanding and improving hospital care. By classifying patients into clinically meaningful and resource-homogeneous groups, DRGs provide a standardized lens through which to analyze hospital utilization, costs, and quality.

The concept of discretionary admissions, revealed through the study of variation in DRG admission rates, highlights the significant role of professional judgment in healthcare decisions. The consistent patterns of variation observed across diverse states underscore that discretionary admissions are a real and measurable phenomenon with broad implications for the healthcare system.

The Index of Discretionary Admissions provides a valuable tool for prioritizing research, guiding utilization review, and informing clinical practice. By focusing on DRG categories with high levels of discretionary admission, we can target efforts to reduce unwarranted practice variations, improve patient outcomes, and enhance the efficiency of healthcare delivery.

Why should you care about DRGs and discretionary admissions? Because they are fundamental to understanding the complexities of modern healthcare. By embracing the insights provided by DRGs and addressing the challenges of discretionary admissions, we can work towards a healthcare system that is more evidence-based, equitable, and delivers greater value to all stakeholders – from healthcare professionals and policymakers to patients themselves.

References

Fetter, R.B., Shin, Y., Freeman, J.L., Averill, R.F., & Thompson, J.D. (1980). Case mix definition by diagnosis-related groups. Medical Care, 18(2 Suppl), 1-53.

Wennberg, J.E., McPherson, K., & Caper, P. (1984). Will payment based on diagnosis-related groups control hospital costs?. The New England Journal of Medicine, 311(5), 295-300.

Knickman, J.R., & Foltz, J.R. (1985). Regional differences in hospital utilization. Medical Care Review, 42(1), 1-46.

Roos, L.L., Fisher, E.S., Sharp, S.M., Newhouse, J.P., Anderson, G.M., & Binns, M.A. (1986). Postsurgical mortality in Manitoba and New England. JAMA, 255(6), 803-805.

Wennberg, J.E., Barnes, B.A., & Zubkoff, M. (1982). Professional uncertainty and the problem of supplier-induced demand. Social Science & Medicine, 16(7), 811-824.

Wennberg, J.E. (1987). Population illness rates do not explain population hospitalization rates. Medical Care Review, 44(2), 235-254.

Roos, N.P., & Roos, L.L. (1982). Surgical rate variations: do they reflect need or practice style?. Medical Care, 20(12), 1183-1195.

Wennberg, J.E., & Gittelsohn, A. (1982). Variations in medical care among small areas. Scientific American, 246(4), 120-134.

McPherson, K., Wennberg, J.E., Hovind, O.B., & Clifford, P. (1982). Small-area variations in the use of common surgical procedures: an international comparison of New England, England, and Norway. The New England Journal of Medicine, 307(22), 1310-1314.

McCracken, J.D., Latessa, J.M., & Wennberg, J.E. (1982). Minor surgery in Maine and Sweden. JAMA, 248(17), 2272-2276.

Deane, R.M., & Ulene, A.L. (1977). Should tonsils and adenoids routinely be removed? No. Patient Care, 11(19), 102-103, 107, 111-112, 115.

Bunker, J.P., McPherson, K., & Henneman, P.L. (1977). оперативные исследования [Surgical research]. Vestnik Khirurgii Imeni I. I. Grekova, 119(11), 137-141.

Harper, R.G. (1962). Critical review of indications for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Pediatrics, 30, 670-682.

Bolande, R.P. (1969). Ritualistic surgery–circumcision and tonsillectomy. The New England Journal of Medicine, 280(11), 591-596.

Dyck, P., Murphy, F., Murphy, J.K., Road, D., Newfeld, P., & Carter, S. (1977). Effect of surveillance on the number of hysterectomies in the province of Saskatchewan. The New England Journal of Medicine, 296(23), 1326-1328.

Wennberg, J.E., Blowers, L., Parker, R., & Gittelsohn, A.M. (1977). Changes in tonsillectomy rates associated with feedback to physicians. Pediatrics, 59(6), 821-826.

McPherson, K., Strong, P.M., Epstein, A., Jones, L., & петрович, н. (1981). Regional variations in the use of common surgical procedures: investigation of the British sources of variation. Sociology of Health & Illness, 3(3), 273-288.

Carter, G.M., & Ginsburg, P.B. (1985). The Medicare case mix index increase. Health Affairs (Millwood), 4(3), 62-72.

Paradise, J.L., & Bluestone, C.D. (1976). Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. The Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 9(2), 341-366.

Department of Health Care Review. (1986). The Maine Medical Assessment Foundation: 1986 report. Augusta, ME: Maine Medical Assessment Foundation.

Gornick, M. (1975). A comparison of hospital use by geographic area. Medical Care, 13(12), 1065-1086.

Wennberg, J.E., Freeman, J.L., & Culp, W.J. (1987). Are hospital services rationed in New Haven or over-utilized in Boston?. Lancet (London, England), 1(8543), 1185-1189.

Lohr, K.N., Brook, R.H., Kamberg, C.J., Goldberg, G.A., Leibowitz, A., Reboussin, B.A., Keesey, J., Sloss, E.M., & Newhouse, J.P. (1986). Effect of cost sharing on use of health services in the health insurance experiment. Medical Care, 24(9 Suppl), S1-S114.