Introduction

Abdominal pain is a frequently encountered complaint in primary care settings, presenting a considerable diagnostic challenge to practitioners. Among the various presentations of abdominal pain, epigastric pain, localized to the upper central region of the abdomen, is particularly common. While many cases of epigastric pain are benign and self-limiting, it can also be a symptom of serious, even life-threatening conditions. Accurate and timely differential diagnosis is crucial in primary care to ensure appropriate management, prevent delays in treatment, and improve patient outcomes.

Primary care physicians are often the first point of contact for patients experiencing epigastric pain. The broad spectrum of potential etiologies, ranging from gastrointestinal disorders to cardiac and pulmonary conditions, necessitates a systematic and thorough approach to assessment. A comprehensive understanding of the differential diagnosis of epigastric pain, coupled with effective history taking, physical examination, and judicious use of investigations, is paramount for primary care practitioners. This article aims to provide a framework for the differential diagnosis of epigastric pain in the primary care setting, emphasizing key considerations for accurate and timely patient management.

Pathophysiology of Epigastric Pain

Understanding the pathophysiology of abdominal pain in general is essential to approaching epigastric pain specifically. Pain in the abdomen arises from various mechanisms, broadly categorized as visceral, parietal (somatic), and referred pain.

Visceral pain originates from the internal organs (viscera) located in the abdomen. In the epigastric region, these organs include the stomach, duodenum, pancreas, liver, and gallbladder. Visceral pain is often described as vague, dull, cramping, or burning, and it is poorly localized due to the innervation patterns of visceral afferent nerves, which often converge in the midline. Stimuli for visceral pain include:

- Inflammation: Such as in gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, and cholecystitis.

- Distension: From conditions like gastroparesis, gastric outlet obstruction, or early bowel obstruction.

- Ischemia: As seen in mesenteric ischemia or splenic infarction.

- Spasm: Of smooth muscle in conditions like biliary colic.

Parietal (somatic) pain arises from the parietal peritoneum, the lining of the abdominal cavity. It is typically more localized and sharp than visceral pain because it is innervated by somatic nerves that are segmentally distributed. Epigastric parietal pain may result from:

- Peritoneal irritation: Due to perforation of a peptic ulcer, leakage of pancreatic enzymes in pancreatitis, or bile leak in cholecystitis.

- Abdominal wall pathology: Such as muscle strain, hernia, or nerve entrapment.

Referred pain is pain perceived in a location distant from the actual source of the pain. Epigastric pain can be referred from:

- Cardiac conditions: Myocardial infarction, angina.

- Pulmonary conditions: Pneumonia, pleurisy.

- Esophageal conditions: Esophageal spasm.

Understanding these different pain mechanisms helps in interpreting the patient’s symptoms and narrowing down the differential diagnosis.

TABLE 1. Pathophysiology of Abdominal Pain Relevant to Epigastric Region

| Process | Example of Disorders in Epigastric Region |

|---|---|

| Inflammation | Gastritis, Peptic Ulcer Disease, Pancreatitis, Cholecystitis, Esophagitis |

| Perforation | Perforated Gastric or Duodenal Ulcer |

| Obstruction | Gastric Outlet Obstruction, Biliary Obstruction (early) |

| Ischemia | Mesenteric Ischemia, Splenic Infarction |

| Spasm | Biliary Colic, Esophageal Spasm |

Source: Adapted from Murtagh J. John Murtagh’s general practice. 4th ed. Sydney: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

TABLE 2. Mechanisms of Abdominal Pain

| Mechanism | Cause | Innervation | Nature | Location |

| —————- | ——————————————————————————————————————————– | ————————————————————– | —————————————————————————————————————————————————————– | ———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————— ————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————{

Epigastric Pain: A Differential Diagnosis Approach in Primary Care

Introduction

Abdominal pain stands as a common complaint prompting patient visits to primary care physicians, presenting a wide array of diagnostic possibilities. Among the various locations of abdominal pain, epigastric pain, situated in the upper central abdomen, warrants particular attention. While many instances of epigastric pain are benign and resolve spontaneously, it can also signal serious underlying conditions demanding prompt and accurate diagnosis. In the primary care setting, the ability to effectively differentiate between these conditions is crucial for appropriate patient management and timely intervention.

Primary care practitioners serve as the initial point of contact for individuals experiencing epigastric pain. The diverse range of potential causes, spanning from gastrointestinal to cardiovascular and pulmonary origins, necessitates a structured and comprehensive approach to assessment. A strong grasp of the differential diagnosis of epigastric pain, combined with skillful history taking, physical examination techniques, and selective use of investigations, is indispensable for primary care doctors. This article aims to provide a practical framework for navigating the differential diagnosis of epigastric pain within the primary care context, emphasizing key considerations for delivering optimal patient care.

Anatomy and Relevant Pathophysiology

The epigastric region, commonly known as the upper central abdomen, is anatomically defined as the area located between the costal margins and below the xiphoid process. Understanding the organs situated in this region is fundamental to formulating a differential diagnosis for epigastric pain. Key organs include:

- Stomach: Responsible for initial food digestion.

- Duodenum: The first part of the small intestine, playing a vital role in digestion and absorption.

- Pancreas: Secretes digestive enzymes and hormones like insulin.

- Liver and Gallbladder: The liver produces bile, stored and concentrated in the gallbladder, essential for fat digestion.

- Esophagus (lower portion): The tube carrying food from the mouth to the stomach.

- Spleen (tail): Part of the lymphatic system, although primarily located in the left upper quadrant, its tail can extend into the epigastrium.

- Abdominal Aorta: The major artery supplying blood to the abdomen and lower body.

Pain in the epigastric region can arise from various pathophysiological mechanisms, including inflammation, distension, ischemia, and functional disorders affecting these organs. As detailed earlier, abdominal pain is broadly categorized into visceral, parietal, and referred pain. Epigastric pain can manifest through any of these mechanisms, often making the diagnostic process complex.

Differential Diagnosis of Epigastric Pain

The differential diagnosis for epigastric pain is extensive. It is helpful to categorize potential causes to ensure a systematic approach. The following categories provide a structured framework for considering possible diagnoses in primary care:

1. Gastrointestinal Disorders:

- Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD): Ulcers in the stomach (gastric ulcer) or duodenum (duodenal ulcer) are classic causes of epigastric pain. Pain is often described as burning or gnawing, may be related to meals (worsening after meals with gastric ulcers, relieved by meals with duodenal ulcers), and can be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and bloating. Helicobacter pylori infection and NSAID use are major risk factors.

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Reflux of stomach acid into the esophagus causes heartburn, often felt in the epigastric region, sometimes radiating upwards. Symptoms are frequently triggered by meals, lying down, or bending over.

- Gastritis and Duodenitis: Inflammation of the stomach or duodenum lining can cause epigastric discomfort, often described as burning or aching. Causes include H. pylori, NSAIDs, alcohol, and stress.

- Pancreatitis: Inflammation of the pancreas, ranging from mild to severe. Epigastric pain is typically severe, constant, and may radiate to the back. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal tenderness are common. Gallstones and alcohol abuse are frequent causes.

- Cholecystitis and Biliary Colic: Inflammation or obstruction of the gallbladder, often due to gallstones. Biliary colic presents with episodic, severe epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, often after fatty meals. Cholecystitis is characterized by more constant pain, fever, and right upper quadrant tenderness.

- Gastric Cancer: While less common in primary care presentations of acute pain, gastric cancer can present with persistent epigastric pain, weight loss, and other alarm symptoms.

- Functional Dyspepsia: Chronic or recurrent epigastric pain or discomfort without identifiable structural or organic cause. Symptoms can mimic PUD or GERD but lack objective findings on endoscopy.

2. Cardiac Conditions:

- Myocardial Infarction (MI): Especially inferior MI, can present with epigastric pain mimicking gastrointestinal issues. Associated symptoms may include chest discomfort, shortness of breath, sweating, and nausea. Risk factors for coronary artery disease should raise suspicion.

- Angina Pectoris: Cardiac chest pain due to myocardial ischemia can sometimes be felt in the epigastrium. Pain is often exertional and relieved by rest or nitroglycerin.

3. Pulmonary Conditions:

- Pneumonia (lower lobe): Irritation of the diaphragm from lower lobe pneumonia can refer pain to the epigastric region. Cough, fever, and respiratory symptoms are usually present.

- Pleurisy: Inflammation of the pleura, the lining around the lungs, can cause sharp pain that may be referred to the epigastrium, often worsened by breathing or coughing.

4. Musculoskeletal Conditions:

- Costochondritis: Inflammation of the cartilage connecting ribs to the sternum. Can cause localized pain and tenderness in the chest wall, sometimes perceived in the epigastric area. Pain is often reproducible with palpation.

- Abdominal Wall Pain: Muscle strain, nerve entrapment (anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome – ACNES), or hernias in the epigastric region can cause localized pain worsened by movement or muscle tensing.

5. Other Conditions:

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA): Rarely, an expanding or dissecting AAA can present with epigastric pain, often described as severe and tearing. Pulsatile abdominal mass may be palpable. This is a life-threatening emergency.

- Splenic Infarction: While the spleen is mostly in the left upper quadrant, infarction can cause pain radiating to the epigastrium.

- Metabolic Disorders: Diabetic ketoacidosis, hypercalcemia, and uremia can sometimes present with abdominal pain, including epigastric pain, though usually with other systemic symptoms.

- Psychogenic Pain: In some cases, epigastric pain can be related to psychological factors like anxiety or somatization disorders, especially when organic causes are excluded after thorough evaluation.

It’s crucial to remember that this is not an exhaustive list, but it covers the most common and clinically relevant differential diagnoses for epigastric pain encountered in primary care.

History Taking: Guiding the Differential

A detailed and targeted history is the cornerstone of differentiating the causes of epigastric pain. Utilizing mnemonic tools like PQRST and PHRASED, as mentioned in the original article, is highly valuable. However, specific questions tailored to epigastric pain are essential:

PQRST for Epigastric Pain:

- P (Provoking/Palliating factors):

- What brings the pain on or makes it worse? (e.g., meals, specific foods, stress, exertion, position)

- What relieves the pain? (e.g., antacids, food, rest, medication, vomiting)

- Q (Quality):

- How would you describe the pain? (e.g., burning, gnawing, sharp, cramping, dull, pressure, squeezing)

- R (Region/Radiation/Referral):

- Where exactly is the pain located? (Point to it)

- Does the pain radiate anywhere else? (e.g., back, chest, jaw, arms)

- S (Severity):

- On a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being the worst pain imaginable, how severe is your pain?

- T (Timing):

- When did the pain start? Was it sudden or gradual onset?

- Is the pain constant or intermittent? How long does it last?

- Is there a pattern to the pain? (e.g., related to meals, time of day, activity)

- Have you had similar episodes before?

Additional Key Historical Questions (adapted from Box 1 of original article & specific to epigastric pain):

- Pain Characteristics:

- Is the pain constant or does it come and go? (Constant pain is more concerning for inflammation or obstruction, intermittent pain for colic or functional issues)

- How severe would you rate it from 1 to 10? (Severe pain necessitates urgent evaluation)

- Have you ever had previous attacks of similar pain? (Recurrent pain may suggest chronic conditions like PUD, GERD, biliary colic, or functional dyspepsia)

- What else do you notice when you have the pain? (Associated symptoms like nausea, vomiting, heartburn, bloating, change in bowel habits, fever, jaundice, chest pain, shortness of breath are crucial)

- Do you know of anything that will bring on the pain? Or relieve it? (Triggers and relieving factors are diagnostically helpful)

- What effect does milk, food, or antacids have on the pain? (Acid-related conditions may respond to antacids or food)

- Gastrointestinal Specifics:

- Are your bowels behaving normally? Have you been constipated or had diarrhea or blood in your motions? (Changes in bowel habits can point towards GI pathology)

- Have you noticed anything different about your urine? (Dark urine can suggest biliary obstruction)

- Have you been vomiting? What does the vomit look like? (Blood in vomit – hematemesis – is an alarm symptom)

- Cardiovascular Risk Factors:

- Do you have any chest pain or discomfort? Shortness of breath? Sweating? (Rule out cardiac causes, especially in at-risk patients)

- Do you have a history of heart problems, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, or smoking? (Assess cardiac risk)

- Medications and Habits:

- What medications do you take, especially NSAIDs or aspirin? (Risk factors for PUD and gastritis)

- How much alcohol do you drink? (Risk factor for gastritis, pancreatitis, liver disease)

- Do you smoke? (Risk factor for PUD, GERD, cardiovascular disease)

- Medical History:

- What operations have you had for your abdomen? (Adhesions can cause obstruction)

- Do you have a history of gallstones, ulcers, pancreatitis, or liver disease? (Prior diagnoses increase likelihood of recurrence or related conditions)

- Red Flags (Alarm Symptoms):

- Unintentional weight loss

- Persistent vomiting

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

- Odynophagia (painful swallowing)

- Gastrointestinal bleeding (hematemesis or melena)

- Anemia

- Jaundice

- Palpable abdominal mass

- Family history of gastrointestinal cancers

Identifying red flags is crucial for prompt referral and further investigation.

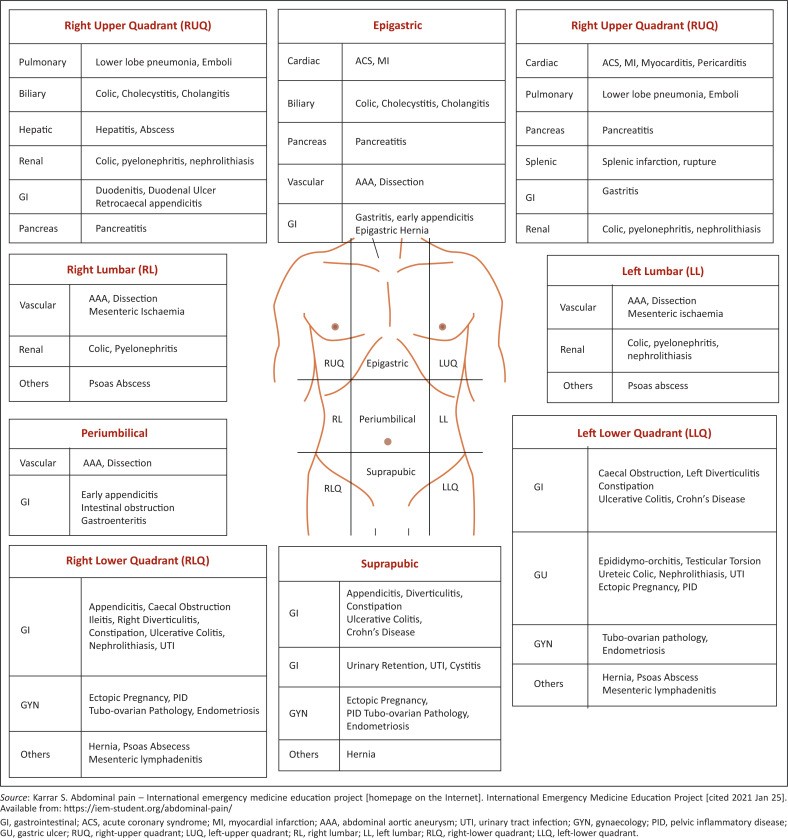

FIGURE 1. Anatomical Localization of Pain in Abdomen

Note: While this figure shows general abdominal regions, focus on the epigastric region for this article’s context.

Physical Examination: Focusing on the Epigastrium

A thorough physical examination, with a particular focus on the abdomen and epigastric region, is vital. General assessment of the patient’s overall condition, including vital signs, is the first step.

Key components of the abdominal examination relevant to epigastric pain:

- Inspection: Observe for abdominal distension, scars, visible pulsations (suggesting AAA), or jaundice.

- Auscultation: Listen for bowel sounds. Hyperactive bowel sounds may suggest early obstruction or gastroenteritis, while absent bowel sounds can indicate ileus or peritonitis.

- Percussion: Assess for tympany (normal) or dullness (organomegaly, mass, fluid). Liver size can be estimated by percussion.

- Palpation: Start with light palpation to identify areas of tenderness, guarding, or rigidity. Progress to deeper palpation to assess for masses or organomegaly.

- Epigastric Tenderness: Localize the area of maximal tenderness. Assess for rebound tenderness (pain worse on release of pressure), suggesting peritoneal irritation.

- Murphy’s Sign: Assess for gallbladder tenderness. Palpate deeply in the right upper quadrant below the costal margin while the patient takes a deep breath. A positive Murphy’s sign (inspiratory arrest due to pain) suggests cholecystitis.

- Palpation for AAA: In older patients, especially with risk factors, gently palpate in the epigastric and umbilical regions for a pulsatile mass.

- Carnett’s Test: To differentiate abdominal wall pain from visceral pain. Perform palpation with the patient supine, noting tenderness. Then, have the patient tense their abdominal muscles by lifting their head and shoulders. If the tenderness increases or stays the same, it suggests abdominal wall pain (positive Carnett’s sign). If it decreases, it is more likely visceral pain (negative Carnett’s sign).

Beyond the Abdomen:

- Cardiovascular Examination: Check heart rate, blood pressure, and listen for heart sounds to assess for cardiac involvement, particularly in patients with risk factors.

- Pulmonary Examination: Auscultate lungs to rule out pneumonia or pleurisy, especially if respiratory symptoms are present.

- Musculoskeletal Examination: Palpate the chest wall and ribs to assess for costochondritis if musculoskeletal pain is suspected.

Rectal and Pelvic Examinations: While not always routinely necessary for epigastric pain specifically, rectal and pelvic exams may be indicated based on the clinical context and differential diagnosis, especially in patients with lower abdominal symptoms, suspected gastrointestinal bleeding, or in women to rule out gynecological causes.

Investigations: Selective and Targeted

Investigations should be guided by the history and physical examination findings to confirm or exclude suspected diagnoses. Routine, indiscriminate testing is not recommended.

Initial Investigations (may be considered in primary care, depending on presentation and risk factors):

- Blood Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To assess for infection (elevated white blood cell count) or anemia (low hemoglobin).

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs): Elevated bilirubin or liver enzymes may suggest biliary obstruction or liver disease.

- Amylase and Lipase: Elevated levels are indicative of pancreatitis.

- Cardiac Enzymes (Troponin): If cardiac ischemia or MI is suspected, especially with chest pain or risk factors.

- Electrolytes, BUN, Creatinine, Glucose: To assess for metabolic disturbances, especially if systemic symptoms are present.

- Urine Analysis: To rule out urinary tract infection, although less directly relevant to epigastric pain unless referred pain is suspected.

- Pregnancy Test (in women of childbearing age): To rule out ectopic pregnancy, although typically presents with lower abdominal pain, epigastric referral is possible.

- Stool Occult Blood Test: If gastrointestinal bleeding is suspected.

Imaging (typically ordered after initial primary care assessment, based on suspected diagnosis):

- Ultrasound: First-line imaging for suspected gallbladder disease (cholecystitis, cholelithiasis), liver disease, and pancreatitis. Also useful for evaluating for AAA (though CT is preferred for rupture).

- Upper Endoscopy (EGD): Indicated for persistent epigastric pain, alarm symptoms (weight loss, bleeding, dysphagia), suspected PUD, gastritis, or to rule out esophageal or gastric malignancy.

- CT Scan of Abdomen and Pelvis: More comprehensive imaging, useful for evaluating pancreatitis, appendicitis (if atypical location), diverticulitis (if affecting the transverse colon and causing epigastric pain), bowel obstruction, AAA, and intra-abdominal abscesses. May be used if ultrasound is inconclusive or to further investigate findings.

- Chest X-ray: To rule out pneumonia or pleurisy if respiratory symptoms are present or if a pulmonary cause of referred epigastric pain is considered.

- ECG (Electrocardiogram): Essential if cardiac chest pain or MI is suspected.

Algorithm for Epigastric Pain (Primary Care Approach):

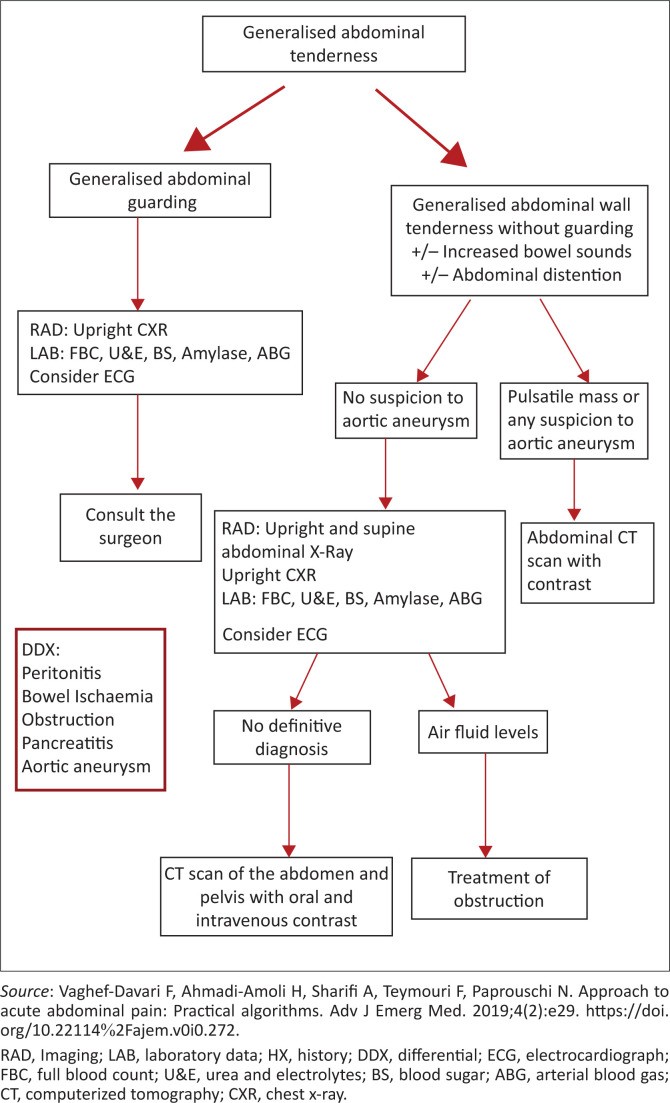

While a detailed algorithm like Figure 2 of the original article focused on generalized abdominal pain is helpful, a specific algorithm for epigastric pain in primary care would be beneficial. However, due to the complexity and broad differential, a rigid algorithm can be limiting. Instead, a stepwise approach is recommended:

- History and Physical Examination: Thorough assessment to categorize pain (visceral, parietal, referred), identify red flags, and narrow the differential diagnosis based on symptom characteristics and risk factors.

- Risk Stratification: Assess for high-risk features (severe pain, hemodynamic instability, red flag symptoms, cardiac risk factors). High-risk patients may require urgent referral or emergency department evaluation.

- Initial Investigations (Selective): Based on suspected diagnoses from history and exam, order appropriate blood tests and consider point-of-care tests (e.g., urine dipstick, ECG).

- Further Imaging/Referral (as needed): If initial investigations are inconclusive or if alarm symptoms persist, consider ultrasound, endoscopy, CT scan, or referral to a specialist (gastroenterologist, cardiologist, surgeon) depending on the suspected diagnosis.

- Symptomatic Management and Reassessment: For low-risk patients with less concerning symptoms, symptomatic treatment (e.g., antacids for suspected GERD) and close follow-up with reassessment are appropriate. Educate patients about alarm symptoms requiring immediate medical attention.

FIGURE 2. Generalised Abdominal Pain Algorithm (Adapted for Epigastric Pain Consideration)

Note: Adapt this generalized algorithm to prioritize differential diagnoses relevant to epigastric pain and primary care context.

Management in Primary Care

Initial management in primary care focuses on:

- Pain Relief: Appropriate analgesia should be provided. For mild to moderate pain, antacids, H2 receptor antagonists, or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may be considered for suspected acid-related conditions. For more severe pain, stronger analgesics may be necessary while awaiting diagnosis, but opioid use should be judicious and after careful consideration of potential masking of symptoms and other risks.

- Symptomatic Treatment: Antiemetics for nausea and vomiting.

- Fluid Resuscitation: If dehydration is present due to vomiting or decreased oral intake.

- Patient Education: Educate patients about their suspected condition, management plan, and alarm symptoms that warrant immediate medical attention.

- Follow-up: Schedule appropriate follow-up to reassess symptoms, review investigation results, and adjust management as needed.

When to Refer

Prompt referral to a specialist or emergency department is crucial in certain situations:

- Red Flag Symptoms: Presence of any alarm symptoms (as listed earlier).

- Severe or Worsening Pain: Pain that is intractable to oral analgesics or progressively worsening.

- Hemodynamic Instability: Tachycardia, hypotension, signs of shock.

- Suspected Serious Conditions: Conditions like AAA, MI, pancreatitis, bowel obstruction, or perforated viscus.

- Diagnostic Uncertainty: If the diagnosis remains unclear after initial primary care assessment and investigations, and symptoms persist or worsen.

Conclusion

Epigastric pain is a frequent and diagnostically challenging complaint in primary care. A systematic approach encompassing a detailed history, thorough physical examination, and selective use of investigations is essential for accurate differential diagnosis. Primary care physicians play a critical role in identifying high-risk patients requiring urgent referral and in managing less severe cases effectively. By considering the broad differential diagnosis, utilizing a structured approach to assessment, and remaining vigilant for alarm symptoms, primary care practitioners can optimize the care of patients presenting with epigastric pain, leading to improved outcomes and timely intervention when necessary.

References

(Include references from the original article and add relevant references for epigastric pain differential diagnosis. For example, guidelines on dyspepsia, abdominal pain, etc.)

Source: Adapted and expanded from Govender I, Rangiah S, Bongongo T, Mahuma P. A primary care approach to abdominal pain in adults. S Afr Fam Pract. 2021;63(1), a5280. https://doi.org/10.4102/safp.v63i1.5280