1. Background

Clinical safety stands as a cornerstone of superior healthcare, emphasizing the proactive identification and mitigation of patient risks inherent within healthcare environments. Adverse Events (AEs), as they are known internationally, represent the materialization of these risks. Minimizing AEs is paramount for healthcare institutions due to their significant impact on patient morbidity and mortality. Notably, a substantial proportion of hospital falls, nearly half, are considered preventable, highlighting the critical need for well-designed systems and processes in healthcare settings [1,2].

Falls within hospitals are a particularly impactful type of AE, reflecting systemic vulnerabilities in organizational structures and procedural execution. The financial burden of hospital falls is considerable, consuming between 1.6% and 13.4% of acute care hospitals’ annual revenues [3,4,5,6,7]. Incidence rates vary from 1.3 to 8.9 falls per 1000 inpatient days in acute care facilities, with approximately 30% resulting in serious injuries [8,9,10]. Beyond physical harm, falls inflict pain, emotional distress on patients and families [3,6], and erode trust in the healthcare system. The economic repercussions extend beyond direct hospital costs, with estimates ranging from 0.85% to 1.5% of total healthcare expenditures in major economies including the United States, Australia, the European Union, and the United Kingdom [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) underscores that these financial costs are compounded by the intangible costs of human suffering and diminished public confidence in healthcare, urging institutions to aggressively pursue the eradication of preventable falls [4,11].

Research consistently identifies individuals with mobility limitations, altered consciousness, advanced age, and sensory impairments as being at heightened risk for falls. The co-occurrence of multiple risk factors significantly elevates this risk [7,12,13,14,15].

A consensus within the literature underscores the value of fall risk assessment in prevention efforts [15,16,17,18]. A systematic review encompassing four meta-analyses of 19 fall-related studies demonstrated that targeted programs and interventions for hospitalized patients can reduce the relative risk of falls by as much as 30% [19].

Several studies highlight the effectiveness of utilizing scales to identify patients at high risk of falls, leading to both a reduction in fall incidents and associated injuries [3,13,15,16,20,21,22]. Kobayashi et al. [3] demonstrated the efficacy of a Fall Assessment Score Sheet in predicting fall risk at admission and during hospitalization, finding a significant correlation between higher risk scores and increased incidence of serious events and falls. Moreira et al. [13] used the MORSE scale in clinical and surgical units and found a significant association between high MORSE scores and fall risk. Schwendimann et al. [15] developed the SAK fall risk scale incorporating factors such as disorientation, frequent urination, mobility limitations, and medication use. Hernandez-Herrera et al. [16] designed a 60-item checklist for fall prevention interventions based on the Nursing Intervention Classification (NIC), with activities related to risk factors, transfers, and patient education being most frequent.

Pasa et al. [21] echoed the effectiveness of the MORSE scale in identifying high-risk patients and observed a correlation between longer hospital stays and increased falls. Hou et al. [22] further emphasized the benefits of using risk assessment tools to enhance nursing control over patient safety.

Nurses, as frontline healthcare providers responsible for initial patient assessments upon hospital admission, are optimally positioned to identify at-risk individuals and implement preventive strategies. Cultivating a culture of responsibility among nurses and leadership, coupled with enhanced training in preventive programs, yields demonstrably positive outcomes [8,9,23,24]. This study investigates the impact of a systematic nursing diagnosis approach, specifically focused on fall risk assessment, as a preventive care measure to decrease hospital falls.

1.1. Theoretical Underpinnings: Virginia Henderson’s Needs Theory

This study’s theoretical framework is anchored in the systematized assessment principles of Virginia Henderson’s Need Theory, a foundational model in nursing care. Henderson conceptualizes the individual holistically, identifying fourteen fundamental needs, one of which is safety and protection from hazards – “avoiding danger.” This safety need, particularly fall prevention, forms the core of our intervention. Reducing falls aligns directly with enhancing patient safety. Within this framework, the nurse’s role is to assist individuals in regaining independence when they lack the strength, knowledge, or will to meet their basic needs, thereby improving their overall safety and well-being [25,26,27].

1.2. Rationale for the Study

The significant scale of the problem of hospital falls, coupled with their serious consequences including pain, injuries, complications, financial costs, and extended hospital stays, underscores the urgent need for interventional studies. Such research is crucial to bolster the evidence base guiding nurses in implementing effective fall reduction practices.

Our central hypothesis was that patients in units where nurses received specialized training in systematic fall risk assessment would experience fewer falls compared to units without such nurse training.

The core question addressed is whether employing an advanced and systematized nursing diagnosis approach, initiated upon patient admission to a hospital unit, effectively reduces the incidence of falls relative to traditional, less structured assessment methods.

1.3. Study Objective

The overarching objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of an educational intervention designed for hospital nurses—focusing on the systematic nursing diagnosis of fall risk—in decreasing the occurrence of patient falls.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study adopted a quasi-experimental design incorporating a non-randomized control group to assess the impact of the nursing intervention. The research was conducted in 2015 within a tertiary hospital located in the Comunitat Valenciana, Spain.

2.2. Participant Selection

Four distinct Care Units with the longest average patient stays were selected for the study: Neurology/Neurosurgery, General Internal Medicine, Nephrology/Vascular Surgery, and Traumatology/Urology. These units were then divided into two groups: an intervention group and a control group, each comprising two Care Units to ensure representation from both medical and surgical specialties. The assignment of units to each group was randomized.

Ultimately, the intervention was implemented in one group (intervention group), consisting of Nephrology/Vascular Surgery and Traumatology units. The control group comprised Internal Medicine and Neurology/Neurosurgery units. Patient assignment was based on the hospital unit where nurses were trained (intervention) or not (control), rather than individual patient randomization.

A minimum sample size of 258 patients per group was determined to be necessary to achieve a 95% confidence level and 80% statistical power, anticipating an approximate AE incidence of 16% in the control group and 8% in the intervention group.

Inclusion criteria: Patients admitted to the selected units (Neurology/Neurosurgery, General Internal Medicine, Nephrology/Vascular Surgery, and Traumatology/Urology) during the study period with a minimum hospital stay of five days (deemed sufficient time for the AE of interest to occur). Sample selection was prospective and consecutive, commencing post-training and continuing until the target sample size was reached from eligible patients.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with pre-existing dementia or delirium were excluded from the study.

A total of 593 patients were initially enrolled, with 12 subsequently excluded (four due to data recording errors and eight who declined participation). No patient deaths or dropouts occurred during the study period.

2.3. Variables Measured

Independent Variables:

- Gender: (Male, Female)

- Age: Categorized in years and age groups (15–50, 51–64, 65–79, ≥80)

- Nursing Units: (General Internal Medicine, Neurology and Neurosurgery, Traumatology and Urology, Vascular Surgery and Nephrology)

- Group: (Control, Intervention)

- Type of Nurse Assessment on Admission: (Traditional, Systematized)

- Fall Risk Assessment on Admission (Downton Scale): (Yes/No) [28]

- Length of Hospital Stay: (Days, categorized as 0–7 and ≥8 days)

- Mobility Level: (Non or impaired, Unaided in room/bathroom, Unaided outside room)

- Surgical Intervention: (Yes/No)

- Altered Consciousness: (Yes/No)

- Nutritional Status on Admission (MNA-SF): (Risk and/or malnutrition, Good nutritional status) [29]

- Oxygen Supply: (Yes/No)

- Catheters: (Vascular access, Nasogastric tubes, Urinary catheterization; categorized as None, One catheter, Two or more catheters)

Dependent Variable:

- Incidence of Falls: (Yes/No)

2.4. Study Procedure

Prior to study commencement, necessary tools were developed for each phase: a detailed protocol for the evaluation team, data collection forms, and a systematic nurse assessment registry for intervention units.

The study spanned eight months, divided into three phases:

Phase 1 (Pre-Intervention Baseline, 2 months): A pilot test was conducted to establish a baseline and refine data collection methods.

Phase 2 (Nurse Training, 1 month): Nurses in the intervention group participated in theoretical and practical training sessions, with reinforcement sessions offered. The intervention centered on a formative activity for nurses in the intervention group. Thirty-three professionals (84.6% of the intervention group nurses) attended the training. The workshop comprised two 4-hour theory and practice sessions, with opportunities for repetition upon request for reinforcement. Pre and post-training self-assessments demonstrated a positive increase in knowledge among participants.

The training program emphasized the initial phase of the nursing process – assessment [24] – within Virginia Henderson’s Human Needs Model [24,25,26]. Systematized assessment was defined as a structured process for gathering comprehensive bio-psycho-social patient information, initiated at admission and continued throughout care, facilitating the identification of potential problems and risks, and informing care plan development. In contrast, the control group utilized traditional assessment methods, characterized by intuition, improvisation, and lack of systematic documentation in patient records.

Phase 3 (Data Collection, 5 months): This period was dedicated to reaching the predetermined sample size. Following systematic patient evaluations in intervention units, care plans were optimized based on newly identified risks. A follow-up process was implemented across all units involving clinical history review, patient/family interviews, and consultations with care professionals to ascertain fall incidence. Blinding was maintained by not informing patients about the assessment method they received.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were recorded in a database and analyzed using SPSS version 20.0 and R version 3.5.1. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and groups, presenting categorical variables as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as means with standard deviations (SD). Fall incidence was analyzed across studied variables.

Bayesian logistic regression was employed to assess the probability of falls between groups, minimizing overfitting by selecting a reduced set of variables. The model was adjusted for length of stay and age as potential confounders, calculating Odds Ratios (OR) with 95% Credible Intervals (CI).

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol received ethical approval from the Hospital’s Research Ethics Committee prior to implementation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data handling adhered to prevailing data protection laws (Law 15/1999 and Law 41/2002). Personal data were securely managed by the research team. The researchers declared no conflicts of interest and no external funding was received for this study.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The final sample comprised 581 patients (97.97% response rate), with 50.6% men and 49.4% women, and a mean age of 68.3 ± 9 years. The control group included 278 patients from General Internal Medicine (23.9%) and Neurology/Neurosurgery (23.9%). The intervention group consisted of 303 patients from Traumatology and Urology (35.5%), and Vascular Surgery and Nephrology (16.7%).

Mean hospital stay was 12.2 ± 9 days, shorter in the intervention group (10.9 ± 7.5 days) than the control group (13.7 ± 0.2 days). Systematic assessment using the Downton scale was applied to 66.3% of patients in the intervention group, compared to 2.9% in the control group (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample Description by Study Group.

| Variables | Totals*n* = 581*n* (%) | Control Group*n* = 278*n* (%) | Intervention Group*n* = 303*n* (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: | |||

| Men | 294 (50.6) | 135 (48.6) | 159 (52.5) |

| Women | 287 (49.4) | 143 (51.4) | 144 (47.5) |

| Mean Age ± Standard Deviation | 68.3 ± 16.2 | 66.78 ± 17.08 | 69.67 ± 15.32 |

| Age Group: | |||

| 15–50 years | 85 (14.6) | 51 (18.3) | 34 (11.2) |

| 51–64 years | 105 (18.1) | 47 (16.9) | 58 (19.1) |

| 65–79 years | 224 (38.6) | 107 (38.5) | 117 (38.6) |

| ≥80 years | 167 (28.7) | 73 (26.3) | 73 (26.3) |

| Nurse assessment on admission: | |||

| Traditional Method | 372 (69) | 269 (96.8) | 103 (34) |

| Systematic method | 209 (31) | 9 (3.2) | 200 (66) |

| Risk assessment of falls on admission: | |||

| Yes | 213 (36.7) | 10 (3.6) | 203 (67.0) |

| No | 368 (63.3) | 268 (96.4) | 100 (33.0) |

| Average Hospital Stay | |||

| ± Standard Deviation (days) | 12.2 ± 9 | 13.71 ± 10.19 | 10.89 ± 7.49 |

| Days interval: | |||

| 0 to 7 days | 205 (35.3) | 76 (27.3) | 128 (42.4) |

| ≥8 days | 376 (63.7) | 202 (72.7) | 174 (57.6) |

| Mobility | |||

| None (bed-to-armchair) | 146 (25.1) | 65 (23.4) | 81 (26.7) |

| Unaided in room/bathroom | 124 (21.3) | 45 (16.5) | 78 (25.7) |

| Unaided outside the room | 311 (53.5) | 167 (60.1) | 144 (47.5) |

| Surgical intervention: | |||

| Yes | 270 (46.5) | 42 (15.1) | 228 (75.2) |

| No | 311 (53.5) | 236 (84.9) | 75 (24.8) |

| Altered consciousness: | |||

| Yes | 59 (10.2) | 41 (14.7) | 18 (5.9) |

| No | 522 (89.8) | 237 (85.3) | 285 (94.1) |

| Nutritional status: | |||

| Risk and/or malnutrition | 272 (46.8) | 150 (54) | 122 (40.3) |

| Normal nutritional status | 309 (53.2) | 128 (46) | 181 (59.7) |

| Supply of Oxygen: | |||

| Yes | 119 (20.5) | 50 (18) | 69 (22.8) |

| No | 462 (79.5) | 228 (82) | 233 (77.2) |

| Catheters (intravenous line, gastric, bladder tube, drainage): | |||

| None | 7 | 5 (1.8) | 3 (1) |

| Has one catheter | 263 | 205 (73.7) | 96 (31.7) |

| Has 2 or more catheters | 308 | 68 (24.5) | 204 (67.3) |

3.2. Fall Incidence

The overall fall incidence was low at 1.2%. Seven falls were reported: one in the intervention group and six in the control group, corresponding to incidences of 0.3% and 2.2%, respectively. Falls were more frequent in men (85.7%), individuals over 65 years (85.7%), and those with hospital stays longer than 7 days (85.7%). All patients who experienced a fall were mobile and had some type of catheter (Table 2).

Table 2. Incidence of Falls.

| Variables | No*n* (%) | Yes*n* (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 288 (50.2) | 6 (85.7) |

| Women | 286 (49.8) | 1 (14.3) |

| Age | ||

| 15–50 years | 85 (14.8) | 0 (0) |

| 51–64 years | 104 (18.1) | 1 (14.2) |

| 65–79 years | 221 (38.5) | 3 (42.9) |

| ≥80 years | 85 (14.8) | 3 (42.9) |

| Nursing Units | ||

| General Internal Medicine | 135 (23.5) | 4 (57.1) |

| Neurology/Neurosurgery | 137 (23.9) | 2 (28.2) |

| Traumatology/Urology | 206 (35.9) | 0 (0) |

| Vascular Surgery/Nephrology | 96 (16.7) | 1 (14.2) |

| Groups | ||

| Intervention | 302 (52.6) | 1 (14.3) |

| Control | 272 (47.4) | 6 (85.7) |

| Nurse assessment on admission | ||

| Traditional Method | 208 (36.2) | 1 (14.3) |

| Systematic method | 366 (63.1) | 6 (85.7) |

| Risk assessment of falls on admission | ||

| No | 212 (36.2) | 6 (85.7) |

| Yes | 362 (63.8) | 1 (14.3) |

| Hospital Stay (days) | ||

| 0–7 days | 204 (35.5) | 1 (14.3) |

| ≥8 days | 370 (64.6) | 6 (85.7) |

| Mobility | ||

| None (bed-to-armchair) | 146 (25.4) | 0 (0) |

| Unaided in room/bathroom | 120 (20.9) | 4 (57.1) |

| Unaided outside the room | 308 (53.7) | 3 (42.9) |

| Surgical intervention | ||

| Yes | 264 (46) | 1 (14.2) |

| No | 310 (54) | 6 (85.7) |

| Altered consciousness | ||

| Yes | 59 (10.3) | 0 (0) |

| No | 515 (89.7) | 7 (100) |

| Nutritional status on admission | ||

| Risk and/or malnutrition | 267 (46.5) | 5 (71.4) |

| Normal nutritional status | 307 (53.5) | 2 (28.6) |

| Supply of Oxygen | ||

| Yes | 117 (20.4) | 2 (28.6) |

| No | 457 (79.6) | 5 (71.4) |

| Catheter (intravenous, gastric/bladder, drainage) | ||

| None | 8 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Has one catheter | 294 (51.2) | 7 (100) |

| Has 2 or more catheters | 272 (47.4) | 0 (28.6) |

3.3. Regression Analysis

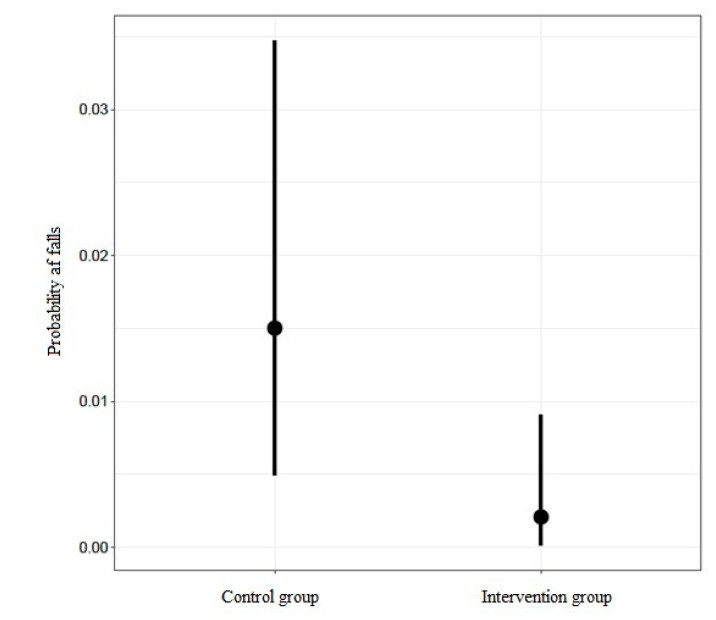

Logistic regression analysis revealed a significantly lower likelihood of falls in the intervention group compared to the control group (OR: 0.127; 95% CI: 0.013–0.821). This finding was strongly supported with a probability of 0.99 and an evidence ratio of 77.43. Neither length of hospital stay nor patient age demonstrated a significant effect on fall probability (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of the Logistic Regression Model.

| Estimate | Std. Error | OR * | Lower 95% | Upper 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −6842 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.088 |

| Intervention Group | −2062 | 0.127 | 0.013 | 0.821 |

| Stay | −0.04 | 0.961 | 0.849 | 1044 |

| Age | 0.045 | 1,046 | 0.991 | 1119 |

| WAIC | 76,754 | 23,922 |

* OR: Odds Ratio.

Figure 1. Probability of falls difference between intervention and control groups illustrating the impact of systematic Nursing Diagnosis For Preventive Care.

Figure 1 illustrates the partial effect of group allocation on fall probability. Dots represent estimated average probability for each group, with vertical lines indicating the confidence interval. The intervention group exhibited a demonstrably lower fall probability compared to the control group. No significant correlation was found between intrinsic risk factors and fall incidence in this analysis.

4. Discussion

The overall fall incidence of 1.2% in this study is notably lower than reported rates ranging from 1.6% to 13.4% of annual hospital income attributed to falls in acute care settings [3,4,5,6,7,30,31].

Patient characteristics associated with falls in our study align with existing literature. Advanced age is a well-documented risk factor [7,14,32,33,34], with 85.8% of fall patients in our study being 65 years or older. Similarly, the higher incidence in men (85.7%) echoes findings in some studies [7,18].

A novel finding is that all fall patients in our study had a catheter, a factor not consistently highlighted in previous research. Consistent with other studies [12,13,22,35], a longer hospital stay exceeding one week was associated with 85.7% of falls. Luzia et al. [7] reported a high proportion of falls occurring between the 10th and 24th days of hospitalization.

Mobility levels also played a role, with all fall patients in our study being mobile, corroborating findings that falls frequently occur in patients with some degree of autonomy [12,15,18,22,32]. This aligns with Lopez-Soto et al. [36], who identified standing, sitting, room entry/exit, and bed transfers as common fall scenarios. Laguna et al.’s systematic review [37] points to preoperative/postoperative status, neurological conditions, and medication as contributing factors, alongside age. Surgical patients are known to have elevated fall risk [7,37,38]. Despite a higher proportion of surgical patients in the intervention group, falls were minimal in this group, further supporting the effectiveness of the educational program.

While altered consciousness is a recognized risk factor [7,13,16,30,32,39], it was not associated with falls in our study.

The significant difference in fall incidence between groups (0.3% intervention vs. 2.3% control) highlights the beneficial impact of systematic assessment, including Downton scale use [28], prevalent in the intervention group. Logistic regression analysis confirmed that the lower fall likelihood in the intervention group was directly associated with the systematic care approach in these units, independent of other variables. These findings are consistent with studies advocating for fall risk assessment scales [3,13,15,16,20,21,22]. Miake-Lye et al.’s systematic review [19] also supports programs integrating risk factor identification in acute care. A study on hospital and nursing home falls emphasized that inadequate preventive care contributes to patient falls [40].

Numerous studies corroborate the value of preventive measures based on identified risk and patient condition [13,15,16,18,20,22,30,32,39]. Avanecean et al. [35] highlighted patient-centered interventions and tailored education as potentially effective fall reduction strategies in acute care.

The training program’s effectiveness in reducing falls underscores that current assessment practices are not always optimal and highlights the necessity of continuous, advanced nurse training. This is consistent with similar studies [8,9,23,24,41,42]. AbuAlRub and Abu Alhijaa [41] found that advanced training for senior nurses improved outcomes and reduced AEs, including falls. Furthermore, advanced training enhances risk detection, enabling targeted preventive strategies within care plans. Preventive education for cancer patients at fall risk has also been shown to significantly reduce falls [42].

Improving nurse clinical practice through advanced training is crucial. Future practice models should incorporate evidence-based strategies like advanced risk assessment training [43]. Systematic reviews emphasize the importance of professional awareness in fall risk reduction [44].

Practical implications include reduced patient falls through protocolized systematic assessment incorporating fall risk evaluation (e.g., catheter presence) and optimized care plans. Following this study, a Systematic Assessment Procedure has been hospital-wide implemented as a valuable tool for AE reduction and care quality improvement.

Addressing voluntary participation in training programs is essential, given the evidence of effectiveness. Nurse training level is a well-established factor in patient outcome improvement [45]. Mandatory training for nurses in high-risk units and further research into advanced training interventions are recommended to enhance professional development and patient safety.

5. Limitations

The “Hawthorne effect” or observer bias may have influenced this study, as nurses in both groups might have altered behavior due to awareness of patient monitoring. Additionally, not all nurses in the intervention group received training (84.6% trained, 66% of patients assessed), meaning some patients in intervention units did not receive systematic risk assessment.

The study focused on assessment process improvement and risk detection, limiting detailed information on patient pathologies and the impact of specific independent variables like surgical intervention. Finally, unit randomization, rather than patient randomization, is a design limitation.

6. Conclusions

Advanced nurse training in fall prevention demonstrably improves patient outcomes. Patients in the intervention group experienced fewer falls, irrespective of age and length of stay. Systematic fall risk assessment during hospitalization is an effective fall reduction intervention, particularly for elderly patients. Mandatory, not voluntary, advanced training for all nurses is recommended. Continued research, especially experimental studies, is needed to strengthen evidence-based clinical practices for patient safety, specifically in fall risk prevention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.-L., I.M.-M. and R.O.-L.; methodology, I.M.-M., R.M.-L. and R.O.-L.; software, M.I.M.-L. and V.G.-C.; validation, V.G.-C., M.I.M.-L. and A.R.-H.; formal analysis, I.M.-M. and R.M.-L.; investigation, I.M.-M. and R.M.-L.; resources, R.O.-L.; data curation, V.G.-C., M.I.M.-L. and A.R.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.-M., R.M.-L. and V.G.-C.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; visualization, R.M.-L., R.O.-L. and V.G.-C.; supervision, R.O-L., V.G.-C., A.R.-H. and M.I.M.-L.; project administration, V.G.-C. and M.I.M.-L. All authors have read and agree the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

[1] World Health Organization. World Alliance for Patient Safety. Summary of the Progress Report on Implementation of the International Classification for Patient Safety (ICPS) Version 1.1. Available online: https://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/icps/icps_progress_report_summary.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2020).

[2] Reason, J. Human error: Models and management. BMJ 2000, 320, 768–770.

[3] Kobayashi, K.; Takahashi, M.; Ishikawa, M.; et al. Risk factors for falls and fall-related injuries in hospitalized patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 469–476.

[4] World Health Organization. Falls. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls (accessed on 15 July 2020).

[5] Heinrich, S.; Rapp, K.; Becker, C.; et al. Hospitalisation due to falls in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 2019, 50, 1333–1346.

[6] Coussement, J.; De Paepe, L.; Schwendimann, R.; et al. Interventions for preventing falls in acute and subacute hospitals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 29–36.

[7] Luzia, M.F.; Luciana, G.R.; Fernanda, M.G.; et al. Factors associated with falls in hospitalized adults: A case-control study. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem 2016, 24, e2795.

[8] Tzeng, H.M.; Yin, C.Y.; Lin, Y.C.; et al. Effectiveness of a fall prevention program in hospitalised older adults: A meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2399–2410.

[9] Oliver, D.; Healey, F.; Haines, T.P. Preventing falls and fall-related injuries in hospitals. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2010, 19, i3–i7.

[10]്യ