1. Introduction

Primary health care (PHC) serves as the cornerstone of effective healthcare systems, aiming to provide accessible, comprehensive, and continuous care to individuals and families within their communities. A fundamental prerequisite for impactful PHC interventions is a thorough understanding of the community itself. This understanding is achieved through community diagnosis, a systematic process that delves into the intricate details of a community’s health status, its determinants, and the needs perceived by its population. Community diagnosis is not merely a data collection exercise; it is a crucial undertaking that lays the groundwork for all subsequent PHC initiatives. It provides the essential context and direction for interventions to be truly effective and community-centered.

The consensus within public health is that interventions must be carefully tailored to the specific needs of the community they are intended to serve. This necessitates a collaborative approach, bringing together healthcare providers, community members, and other stakeholders to jointly identify health needs and strategize effective solutions. This collaborative process should consider the diverse factors influencing community health and develop models and strategies that are contextually appropriate and culturally sensitive. When community diagnosis is executed effectively, it not only identifies health needs but also fosters stronger connections among community actors, including residents, public health professionals, and local institutions. This strengthened network empowers the community, cultivates local leadership, and facilitates the implementation of community-driven action plans. Evaluating the effectiveness of the community diagnosis process itself is also crucial, ensuring continuous improvement and maximizing its impact on community health outcomes.

The conceptual foundation of community diagnosis rests on a broad understanding of health. Health is not simply the absence of disease; it is a fundamental human right and a dynamic, multifaceted experience shaped by individual, social, economic, cultural, and environmental factors. Community health, therefore, is the collective health of individuals and families within a shared environment. It encompasses social, cultural, and environmental characteristics, access to and quality of health services, and the profound influence of social, political, and global determinants of health. Recognizing these social determinants is paramount in community diagnosis, as they often represent the root causes of health inequities and offer key leverage points for intervention.

A comprehensive approach to community diagnosis necessitates a holistic paradigm. This involves characterizing the community by thoroughly investigating the social determinants of health prevalent within it. It also requires understanding the lived experiences of community members, adopting a multidimensional view of health that encompasses physical, mental, and social well-being. This positive and holistic perspective moves beyond a deficit-based approach, focusing on community strengths and assets alongside challenges and needs.

By its very nature, a community approach to health is participatory. Community diagnosis, as a community-driven process, demands the active involvement of three key groups: administrative bodies (local and regional), technical and professional resources (frontline workers in health, education, social services, etc.), and community members themselves. Citizen participation extends beyond individual residents to include social organizations, formal and informal community groups, and active participants in community life. This inclusive participation ensures that the diagnosis truly reflects the community’s perspectives and priorities, leading to more relevant and sustainable interventions.

Engaging women in community diagnosis is particularly important. Women often play central roles in families and communities, possessing unique insights into health needs and social dynamics. Their participation ensures a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of community health, leading to more effective protection, promotion, and self-care strategies for women and the community as a whole. Including women in the process recognizes their valuable roles in maintaining traditional knowledge, shaping health attitudes, and acting as agents of change within their communities. While some studies acknowledge women as informants in community diagnoses, their involvement in decision-making and action planning is often limited. Genuine community participation, where residents are active partners in shaping the diagnostic process and its outcomes, remains relatively scarce.

Examples of community-participatory health diagnoses exist, offering valuable models for practice. Studies in Spain, for instance, have explored citizen perceptions of well-being, quality of life, and community health needs beyond individualistic frameworks. Other initiatives have focused on collaborative diagnoses involving residents, workers, and service providers in specific neighborhoods to improve quality of life and guide program development. Furthermore, examples from Latin America and Europe, including projects associated with the Healthy Cities movement, demonstrate the application of community diagnosis in diverse contexts. These studies highlight the use of mixed methods, including desk reviews, focus groups, and interviews, to gain a holistic understanding of community needs and potential solutions. However, many of these past efforts have primarily focused on identifying priorities for intervention, often lacking robust follow-up mechanisms or evidence of long-term implementation and impact. Crucially, a gender perspective is frequently absent from these community diagnosis processes, limiting their ability to fully address the diverse health needs of all community members.

This article aims to illuminate the crucial Roles Of Community Diagnosis In Primary Health Care, drawing upon the insights from a participatory community diagnosis conducted in a rural Spanish community. By examining the methodology, findings, and outcomes of this case study, we aim to underscore the value of community diagnosis as a tool for understanding community health needs, empowering communities, and driving meaningful improvements in primary health care delivery.

2. Materials and Methods

The community diagnosis study presented here adopted a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, combined with qualitative data collection and analysis methods rooted in ethnography. This methodological framework is particularly well-suited for community diagnosis as it emphasizes community engagement, shared ownership of the research process, and in-depth understanding of community culture and context. Ethnographic methods provide rich contextual data, capturing the history, social dynamics, and cultural nuances of the community. This approach allows researchers to gather individual perspectives within the broader community context, facilitating a deeper interpretation of community values, beliefs, and behaviors related to health.

The study was conducted in Mañaria, a rural community in northern Spain with approximately 522 inhabitants at the time of the study. The population was distributed across an urban center, several neighborhoods, and dispersed rural dwellings, typical of the region. The study focused on women’s perspectives, recognizing their central roles in community health and their often-underrepresented voices in health research and planning.

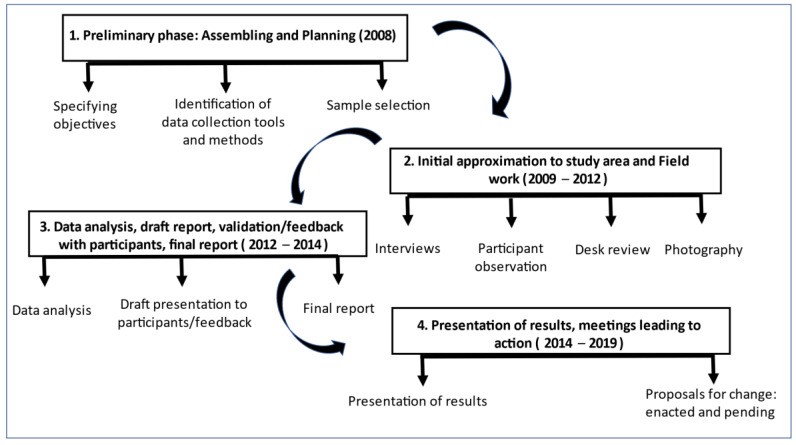

Data collection occurred in two phases, conducted in 2009 and 2014. Following data collection and initial analysis, the research team returned to the community to present preliminary findings, seeking community validation and collaboratively identifying potential action proposals to address identified challenges and leverage community strengths. This iterative process ensured that the research findings resonated with community members and that proposed actions were relevant and feasible within the local context. The community’s enthusiastic response led to the presentation of these proposals to local authorities, resulting in the approval and implementation of several community-led initiatives by the study’s conclusion in 2019. The entire study, from initial data collection to implementation of action proposals, spanned from 2008 to 2019, reflecting the commitment to community engagement and action-oriented outcomes.

The participant sample included 21 women, selected through purposive sampling to maximize diversity in age, socio-demographic characteristics, and geographical location within the community. In addition, five key informants were recruited based on their in-depth knowledge of community health issues and their ability to provide valuable insights. Key informants included women working in local health and social services, as well as active community members with extensive social networks. Data collection continued until data saturation was reached, meaning that further interviews yielded no new relevant information, ensuring the comprehensiveness of the data collected.

Data collection methods were diverse and triangulated to provide a rich and multifaceted understanding of community health. These methods included participatory observation, in-depth interviews, semi-structured interviews, desk review of existing community data, and photography to document community environments and activities. Participatory observation involved researchers immersing themselves in community life, attending community events, and observing daily interactions and routines. In-depth interviews, primarily open-ended and exploratory, allowed for a deep understanding of individual experiences, perspectives, and narratives related to community health. Semi-structured interviews used a topic guide to systematically explore pre-defined themes related to community diagnosis, ensuring comprehensive coverage of key areas.

Initial in-depth interviews were open-ended, exploring broad questions about community health perceptions, valued aspects of the community, and areas for potential improvement. These exploratory interviews helped identify key themes and issues to be further investigated in semi-structured interviews. Semi-structured interviews then focused on specific topics, including demographic structure, economic activities, urban environment, social systems, and formal and informal health care systems. The interview guides evolved iteratively based on emerging themes from the ongoing data collection.

Interviews were conducted in both Spanish and Euskera, the local Basque language, to facilitate rapport and ensure comfortable communication with participants. Using the local language was particularly valuable for building trust and eliciting richer narratives from Euskera-speaking participants.

Participatory observation occurred across various settings and times, capturing the diversity of community life and health-related behaviors. One of the researchers resided in the community during the fieldwork period, enhancing opportunities for prolonged observation and deeper community immersion. Field notes documented observations, reflections, and emerging insights, complemented by photographs of community spaces and relevant environmental factors. These visual and textual records provided valuable context for data analysis and interpretation, particularly in understanding the impact of local industries like quarries and community initiatives like “auzolana” (community work).

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for subsequent text analysis. Data analysis followed an inductive approach, beginning with manual coding of interview transcripts and field notes to identify recurring themes and patterns. Codes were then grouped into categories and meta-categories based on thematic similarities and relationships, following the principles of grounded theory. This iterative process of coding, categorization, and comparison allowed for the emergence of key thematic nuclei that represented core dimensions of community health in Mañaria. Data triangulation, using multiple data sources (interviews, observations, documents, photographs), strengthened the validity and robustness of the findings.

Preliminary findings were presented back to the 26 participant women for validation and refinement. This feedback process not only ensured the accuracy and community relevance of the findings but also fostered further discussion and nuanced understanding of the data. Participants’ insights led to revisions and clarifications of the researchers’ interpretations, emphasizing the collaborative nature of the research process. Following community validation, the finalized findings were presented at a public forum at the Town Hall, initiating community-wide dialogue and engagement with the research outcomes. This public presentation served as a catalyst for community action, leading to discussions with local political and health authorities and contributing to community empowerment.

The study adhered to ethical guidelines outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and received ethical approval from the relevant Institutional Review Board. Informed oral consent was obtained from all participants prior to interviews and audio recording. Anonymity and confidentiality were rigorously maintained throughout the research process. The COREQ guidelines for qualitative research reporting and established criteria for qualitative research validity were followed to ensure the rigor and trustworthiness of the study.

3. Results

3.1. The Sample

The study sample comprised 26 women, including 21 participants recruited through purposive sampling and 5 key informants. The average age of participants was 47 years, representing a diverse age distribution across different life stages. The sample included women from all geographical areas within Mañaria, ensuring representation from both the urban center and surrounding neighborhoods.

Key informants included professionals working in the local town hall, social services, and health system, as well as a representative from a prominent local civil association. These key informants provided valuable perspectives from institutional and community organization levels, complementing the insights from individual participant interviews.

3.2. Meta-Categories and Thematic Nuclei

The data analysis process yielded six meta-categories and associated thematic nuclei that captured the key dimensions of community health identified in Mañaria. These categories provided a framework for understanding the complex interplay of factors influencing community well-being.

These meta-categories encompassed a broad range of factors, from population characteristics and economic activities to public and private spaces, lifestyles, socialization processes, and health care resources. Within each meta-category, specific thematic nuclei emerged, representing key areas of concern, strength, or potential intervention. For each thematic nucleus, the study identified existing problems or areas for improvement, community health assets or strengths, and potential proposals for change. The identified problems, assets, and proposed actions reflected a comprehensive understanding of health, extending beyond the traditional health sector to encompass social, economic, cultural, and environmental determinants.

3.3. Meta-Categories

3.3.1. Population

This meta-category highlighted issues related to housing affordability and availability, limited local employment opportunities, environmental impacts of the quarry industry, and gaps in community services. Participants expressed concern that these factors negatively impacted the community’s demographic development and overall health. They emphasized that these were not merely individual concerns but collective issues requiring community-level solutions. Proposed changes included urban improvements and the construction of new housing to address housing shortages and improve living conditions. Notably, by the end of the study, progress had been made in both urban development projects and housing initiatives.

3.3.2. From Home to Community Economics

Participants identified three interconnected types of work contributing to individual, household, and community economic well-being: non-remunerated domestic work, remunerated employment, and community participatory work (“auzolana”). Women highlighted their central role in managing domestic work and reconciling work-life balance. They also recognized the psychological and social benefits of paid employment, alongside its economic necessity. “Auzolana,” community-based collaborative work, was identified as a significant community asset, fostering social cohesion and collective action. Action proposals focused on valuing and socializing domestic work, supporting local small businesses, and strengthening “auzolana” traditions. Annual “auzolana” planning meetings were subsequently established, and participatory budgeting processes were implemented to involve citizens in local resource allocation decisions.

3.3.3. Public and Private Spaces

Public and private spaces were recognized as crucial determinants of daily life and community health. The rural character of Mañaria was valued for its quality of life benefits compared to urban centers. However, concerns were raised about public spaces, including the environmental impact of quarries, traffic safety on the main highway, architectural barriers, waste management, and limited accessibility to essential services. Private space concerns included comfort, accessibility, tranquility, safety, overcrowding, building maintenance, and neighborly relations. A key action proposal was to improve public transportation options connecting Mañaria to nearby cities, which was implemented during the study period.

3.3.4. Habits and Lifestyles

This meta-category explored daily routines and lifestyle choices impacting health. Eating habits reflected local traditions and access to homegrown produce, with positive aspects including vegetable consumption and family meals. However, lower fish consumption compared to meat was identified as an area for potential dietary improvement. Alcohol consumption was primarily social and weekend-focused. Smoking was prevalent among a subgroup of participants, highlighting opportunities for smoking cessation support. While most participants reported adequate sleep, some experienced sleep disturbances related to environmental factors or mental well-being. Leisure and free time activities, particularly outdoor recreation, were recognized as important for physical, mental, and social health. Action proposals focused on promoting physical activity, leading to the establishment of public exercise spaces and community gym programs.

3.3.5. Socializing Process

Socialization venues and processes were identified as essential for community cohesion and individual well-being. Formal socialization spaces included schools and childcare facilities, while informal spaces encompassed churches, cultural centers, sports facilities, town squares, and community centers. Participants emphasized the importance of community integration and healthy social interactions. Action proposals aimed to strengthen community integration and promote positive socialization, leading to the creation of youth activity programs, cultural spaces for adolescents, and expanded community-based activities.

3.3.6. Health Care Resources

Participants frequently provided informal care to family members, highlighting the crucial role of informal caregivers within the community. Family and social networks were identified as key resources for care and support. Formal health care services in Mañaria included a local doctor’s office with a physician and nurse, offering home visits and generally perceived as providing kind and efficient care. However, areas for improvement were identified, including the need for pediatric services, expanded service hours, enhanced team coordination, and a broader range of on-site services. Action proposals included advocating for improved pediatric emergency services in the region and offering community-based health education sessions on relevant health topics. Health education sessions were subsequently implemented, addressing topics such as back pain, pelvic floor health, child bereavement, sexuality, and first aid.

4. Discussion

This community diagnosis study underscores the critical roles of community diagnosis in primary health care. Our approach, rooted in social determinants of health and participatory methodologies, emphasized a comprehensive and multidimensional understanding of community life. A key innovation was the deliberate focus on empowering women as central informants and active participants in the diagnostic process. This aligns with current trends in primary health care that recognize the importance of empowering women to protect and promote health, engage in self-care, and facilitate dialogue between communities and health institutions. While other studies have adopted comprehensive approaches to understanding health determinants, our study uniquely integrated this theoretical framework with the active leadership and operational contributions of women informants. By valuing women’s nuanced perspectives and incorporating their feedback throughout the research process, we moved beyond simply gathering information to co-creating knowledge and action plans with the community. This iterative process of community validation and refinement strengthened the relevance and impact of the study findings.

The empowerment of women participants extended beyond their role as informants. By involving them in the discussion of findings and action planning, the study fostered co-participation in the community health diagnosis. This empowered women to negotiate for resources and advocate for the implementation of community-identified solutions. This participatory approach, aligning with a gender-sensitive perspective in primary health care, positions women as agents of change in promoting community health and well-being.

Our approach was further supported by regional health policy frameworks in the Basque Country, which emphasize community action and proactive strategies for health improvement. The study’s early and consistent engagement with local authorities fostered trust and collaboration, strengthening the credibility of the research and facilitating the translation of findings into concrete action. The dissemination of the study report to the Town Council and community library ensured broad access to the findings and recommendations, further contributing to community ownership and action. The convergence of interests among community participants, local government, and the research team created a synergistic environment for enacting meaningful community health improvements.

The rural context of Mañaria significantly shaped the findings of the community diagnosis. The study documented the renewed appreciation for rural living as a setting conducive to health, offering access to nature, tranquility, and a slower pace of life compared to urban environments. However, the limitations of rural settings, particularly regarding access to public services, were also highlighted as challenges to rural development and demographic sustainability. Addressing these service gaps through targeted policy interventions is crucial to support rural communities and capitalize on their health-promoting potential.

The quarry industry emerged as a significant environmental and health concern in Mañaria. The negative impacts of quarry operations on air quality, noise levels, and overall quality of life were strongly voiced by participants. Community mobilization and legal action against one quarry, resulting in its closure, demonstrate the community’s agency in addressing environmental health threats. This outcome underscores the importance of community diagnosis in identifying and addressing environmental determinants of health.

The study findings also highlighted the significance of community spaces and collective activities for social cohesion and health. Participants valued public spaces as settings for social interaction, safety, and community building. “Auzolana,” the tradition of community-based voluntary work, was identified as a powerful instrument for fostering social connectedness and achieving shared goals. While research on community activities for health promotion exists, the specific role of “auzolana” as a mechanism for community participation and health improvement warrants further investigation.

Methodologically, the qualitative approach adopted in this study proved highly effective for community diagnosis, aligning with the experiences of other researchers. The ethnographic approach, including participant observation, provided rich contextual data and facilitated a deeper understanding of community dynamics. While the researcher’s immersion in the community through participant observation could potentially introduce bias, the extended fieldwork period and language fluency likely mitigated this risk, fostering trust and rapport. The longitudinal nature of the study, extending beyond initial data collection to community validation and action implementation, was a strength, ensuring that the diagnosis was not merely an academic exercise but a catalyst for tangible community change.

A limitation of the study is its focus on women’s perspectives, potentially overlooking men’s experiences and viewpoints. While women’s central roles in family and community health were a key rationale for this focus, future community diagnoses could benefit from incorporating diverse perspectives, including those of men, to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of community health needs and priorities.

Despite this limitation, the study successfully identified key community health problems and assets. The identification of health assets, alongside needs and challenges, represents a valuable addition to the community diagnosis framework. Focusing on community strengths and resources can inform asset-based approaches to health promotion and community development, building upon existing capacities and fostering community resilience. The integration of health assets into the community diagnosis process, as demonstrated in this study, offers a promising direction for future research and practice.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the multifaceted and essential roles of community diagnosis in strengthening primary health care. A qualitative, participatory approach, prioritizing the voices and experiences of women, proved highly effective in understanding community health needs, identifying social determinants of health, and fostering community action. The iterative process of community validation and the integration of health assets into the diagnostic framework further enhanced the study’s relevance and impact. The study’s success in translating findings into concrete community-led initiatives underscores the transformative potential of community diagnosis as a tool for empowering communities and driving meaningful improvements in primary health care. This approach holds promise for replication in diverse settings, contributing to a growing body of knowledge and experience in community-based participatory approaches to health improvement.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all participants in this study as well as every person who contributed information. The authors also acknowledge the community town hall for facilities extended to the researchers and for considering in their work plan the proposals for community improvement that resulted from this study. Special thanks to Carole Bernard for her help in editing the English version of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; methodology, M.J.A.-E., E.R.-V. and H.M.; software, M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; validation, H.M., M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; formal analysis, M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; investigation, M.J.A.-E.; data curation, M.J.A.-E.; writing—review and editing, H.M., M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; supervision, H.M., M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; project management, H.M., M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of UNIVERSIDAD PÚBLICA DEL PAÍS VASCO-EUSKAL HERRIKO UNIBERTSITATEA (protocol number CEISH/80/2011, on 12 September 2011).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available in deference to participants, who were not informed that their replies, even when de-identified, would be made publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[1] Baez, K.; Spencer, C.; Kieffer, E.C.; Rosas-Lee, M.; Janisse, J.; Tu, S.P.; Palmisano, G. Community diagnosis and participatory approaches for community health improvement. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2009, 3, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2] Laverack, G. Why population health promotion? Health Promot. Int. 2001, 16, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3] Rifkin, S.H.; Lewando-Hundt, G.; Draper, A.K. Reaching the poor: A community-based health programme in rural India. Health Policy Plan. 1991, 6, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[4] World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

[5] Muntaner, C.; Borrell, C.; Ng, E.; Chung, H.; Espelt, A.; Rodriguez-Sanz, M.; Benach, J. Politics, welfare regimes, and population health: The Spanish paradox. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6] World Health Organization. Health Promotion Evaluation: Recommendations to Policymakers; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998. [Google Scholar]

[7] Nutbeam, D. Evaluating Health Promotion—Progress, Problems and Solutions. Health Promot. Int. 1998, 13, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[8] Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Background Document to WHO—Europe Summer School on Social Determinants of Health; University of Liverpool: Liverpool, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

[9] Marmot, M.; Wilkinson, R.G. Social Determinants of Health, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

[10] Rifkin, S.H.; Pridmore, P. Partners in Planning: Information, Participation and Empowerment. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2001, 16, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11] Narayan, D. Voices of the Poor. Can Anyone Hear Us? Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

[12] Cornwall, A.; Jewkes, R. What is participatory research? Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[13] George, M.; Rubin, G.; Donnermeyer, J.F. Women’s Voices in Community Health Assessment: A Case Study of Appalachian Kentucky. J. Community Pract. 2005, 12, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[14] Flicker, S.; Travers, R.; Guta, A.; Miskovic, M.; Woodford, M. Ethical dilemmas in community-based participatory research: Case studies from the field. Health Promot. Pract. 2008, 9, 28S–36S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15] Gibson, K.; Williams, L.; ممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممmmmmمممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممممم