Introduction

Sepsis, a life-threatening condition arising from the body’s dysregulated response to an infection, remains a global health crisis. Affecting millions annually, sepsis can rapidly progress, leading to organ dysfunction, septic shock, and death if not promptly and appropriately managed.1 Globally, estimates from 2016 indicate a staggering 31.5 million sepsis cases, resulting in 5.3 million fatalities.2 In the United States alone, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report sepsis as being associated with one in three hospital deaths.3 Neonatal sepsis is particularly devastating, with the World Health Organization (WHO) estimating over 1 million newborn deaths each year due to this condition.4 The urgency in sepsis management is underscored by the fact that for every hour treatment is delayed, survival rates decrease by approximately 7.7%.10

Currently, sepsis diagnosis heavily relies on clinical assessment and laboratory investigations. The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, established by the Third International Sepsis Consensus Task Force in 2016, serves as the standard diagnostic criterion.5 SOFA evaluates organ dysfunction across respiratory, coagulation, liver, cardiovascular, central nervous system, and renal systems. While SOFA marked an improvement over the previous Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria,6 it still presents limitations. SOFA scoring is complex, requires multiple measurements, and lacks specificity, leading to misdiagnosis in roughly 30% of cases.9 This can result in unnecessary antibiotic use, contributing to antibiotic resistance and increased healthcare costs.9 Furthermore, SOFA relies on laboratory infrastructure that may be lacking in resource-limited settings, hindering timely diagnosis and intervention globally.

The critical need for rapid and accurate sepsis diagnosis has spurred the development of point-of-care (POC) technologies. POC diagnostics offer the promise of delivering timely, actionable information at the patient’s bedside or in resource-constrained environments.11 These technologies are designed to be user-friendly, cost-effective, and rapid, often requiring minimal infrastructure.12 Various POC platforms, including microfluidics,13 lateral flow assays,14,15 dipsticks,15 and smartphone-integrated devices,16 are being explored for sepsis biomarker detection. These platforms can analyze minute sample volumes, such as a fingerprick of blood, and operate with compact devices or basic laboratory equipment, making them ideal for diverse healthcare settings.12 Studies have shown that POC testing in hospital emergency departments can reduce care times by approximately one hour compared to traditional lab testing, potentially improving patient outcomes and reducing costs.18 Beyond sepsis, POC diagnostics are being actively developed for various applications, including nutrition,19–22 infectious diseases,11,13,23 cancer,24–27 and HIV/AIDS.28–30

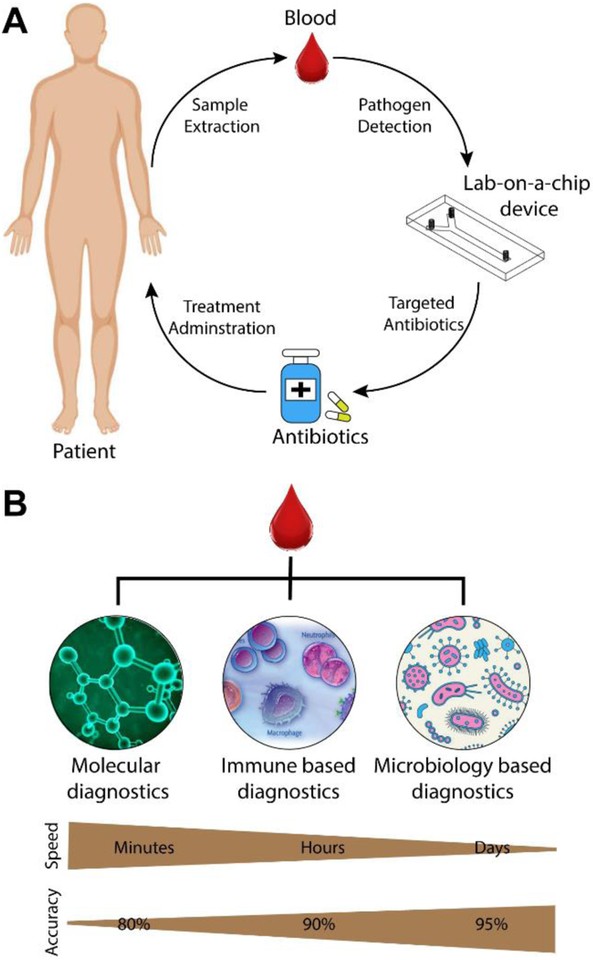

For sepsis management, POC diagnostics hold immense potential for risk stratification, guiding initial treatment decisions, monitoring disease progression, and evaluating treatment response (Figure 1A).31 Ideally, POC sepsis tests should provide results within minutes to facilitate timely antibiotic administration and prevent disease progression. The performance requirements for POC sepsis tests may vary depending on the setting. In well-resourced hospitals, high diagnostic accuracy is crucial to compete with established laboratory methods, while in low-resource settings, affordability, ease of use, and long shelf life may be prioritized.

Figure 1. Point-of-Care Sepsis Diagnostic Applications and Biomarker Categories

Research in POC sepsis diagnostics has focused on various biomarkers, broadly categorized into blood plasma proteins, leukocyte monitoring, and pathogen detection (Figure 1B). Blood plasma protein biomarkers include C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), interleukins, and lactate. Leukocyte monitoring involves assessing immune cell activity through antibody capture or intrinsic property characterization. Pathogen detection employs diverse techniques such as magnetic separation. This review explores the landscape of developing and commercially available POC technologies for sepsis diagnosis, evaluating their advantages and limitations, with a focus on studies from the past decade relevant to POC applications. Comprehensive reviews on sepsis biomarkers beyond POC and the pathophysiology of sepsis can be found in other publications.32–38

Point-of-Care Assays for Blood Plasma Protein Biomarkers in Sepsis

Sepsis triggers a complex cascade of immune responses, leading to the altered expression and secretion of various proteins into the bloodstream. These proteins, including cytokines, interleukins, acute-phase proteins, and receptor proteins, serve as potential biomarkers for sepsis diagnosis. Among these, interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin (PCT) are the most extensively investigated biomarkers for POC sepsis diagnostics.39

IL-6, a cytokine released early in infection, exhibits a strong correlation with sepsis severity and patient outcomes. Decreasing IL-6 levels are indicative of improved survival.40,41 Meta-analysis data reveals a moderate diagnostic sensitivity for IL-6, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) value of 0.79.36 CRP, an acute-phase protein, is produced in response to cytokines like IL-6.42 CRP demonstrates an AUROC value of 0.77 for sepsis diagnosis.36 PCT release is associated with the severity of bacterial infection,43 with a half-life of approximately 24 hours and a higher AUROC value of 0.85.36 Similar to IL-6, declining PCT levels are associated with better patient survival.39 Notably, the combination of IL-26 and PCT has shown enhanced diagnostic performance compared to either biomarker alone.44 Numerous other proteins, including lactate, sTREM-1, neopterin, TNF-α, E-selectin, S-100, presepsin, LBP, CD64, DcR3, endocan, sICAM-1, and C3a, have been explored as potential sepsis biomarkers.36 While some of these markers exhibit promising AUROC values exceeding 0.9, further research is needed to validate their clinical utility in POC settings.

Simpler, single-analyte POC devices are being actively developed and tested for sepsis diagnosis. Blood lactate levels, for instance, are utilized as a standalone biomarker for risk stratification in emergency room patients.45 Studies have shown that fingerprick lactate testing can significantly reduce the time to results compared to standard laboratory analysis, accelerating clinical decision-making.46 Microfluidic devices for POC detection of PCT have also been developed, demonstrating rapid detection within ten minutes with high sensitivity.47 The PATHFAST assay, a commercially available test for presepsin detection, has shown higher specificity compared to other single biomarkers for sepsis.48,49 This chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay can analyze whole blood samples, providing results in approximately 17 minutes. Biochip platforms are also being adapted for POC sepsis diagnosis, with devices capable of sensing IL-6 within 5 minutes using latex beads and achieving a detection limit of 127 pg/mL.50

Smartphone-based POC devices are gaining traction in sepsis diagnostics due to their accessibility and versatility. These devices often integrate smartphone capabilities for image acquisition, data processing, communication, and user interface. An example is a smartphone-enabled POC device for IL-3 detection, which can provide results within one hour and has demonstrated a high AUROC value of 0.91 (Figure 2).53 The widespread familiarity and ease of use of smartphones make these integrated POC solutions particularly attractive for diverse healthcare settings.54

Figure 2. Smartphone-Enabled Point-of-Care Interleukin Detection Device

Multiplexed biomarker detection, simultaneously measuring multiple biomarkers, holds the potential to enhance diagnostic accuracy and provide a more comprehensive assessment of sepsis. Research suggests that biomarker panels, such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, interleukin-1ra, and Protein C, may be more effective for patient risk assessment in sepsis.55 Miniaturized protein microarray chips are being developed for multiplexed detection of sepsis biomarkers, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF alpha, S-100, PCT, E-Selectin, CRP, and Neopterin.56 These devices are being tailored for neonatal sepsis POC testing, utilizing small sample volumes (e.g., 4μL), single-step processing, and reduced incubation times, while maintaining sensitivity through innovations like streptavidin-conjugated magnetic particles for enhanced mixing and binding.[57](#R57] Microarray biochips for detecting CRP, IL-6, PCT, and NPT using on-chip immunofluorescence assays within 25 minutes have also been reported.58 Magnetic lab-on-a-chip devices employing embedded magnetoresistive sensors for detecting sepsis-related cytokines like IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α are another promising avenue in multiplexed POC sepsis diagnostics.59

Leukocyte-Based Point-of-Care Sepsis Diagnostics: Harnessing Intrinsic Immune Properties

Beyond soluble biomarkers, monitoring the systemic inflammatory response through leukocyte analysis offers a valuable approach for POC sepsis diagnostics. Immune paralysis, a state of immune dysfunction, is common in later stages of sepsis, making early assessment of immune response crucial for diagnosis and monitoring disease progression. Neutrophils, the most abundant type of white blood cells, have garnered significant attention due to their dynamic changes in morphology, mechanics, and motility during sepsis.1,59–62 Neutrophil CD64 expression, a surface marker, has been shown to increase under septic conditions, emerging as a potential biomarker.63,64 Neutrophil CD64 upregulation can occur as early as one hour after bacterial infection, highlighting its potential for rapid sepsis detection.68

POC devices leveraging neutrophil CD64 expression for sepsis diagnosis are under development. A POC device employing a herringbone-shaped cell capture chamber for affinity separation of CD64-expressing neutrophils within 2 hours has demonstrated promising results, achieving an AUROC of 0.90 compared to qSOFA-based sepsis diagnosis in a pilot clinical trial.69 Expanding this technology to include CD69, another neutrophil activation marker, further improved the diagnostic performance, reaching an AUROC of 0.98 in a study with qSOFA-positive clinical samples.70

Iso-dielectric separation, a technique that differentiates cells based on their electrical properties, has been explored for leukocyte-based sepsis diagnostics. This approach can distinguish between activated and non-activated leukocytes based on their electrical profiles. Studies in mouse models have shown strong correlations between on-chip electrical cell profiling and flow cytometry, a standard laboratory technique for immune cell analysis.71 While offering potential for continuous sepsis monitoring, this technology is still in preclinical development.

Microfluidic biochips for electrically quantifying CD64 antigen expression on neutrophils are also being developed for POC applications (Figure 3A).72 These devices can deliver test results within 30 minutes and offer an alternative to traditional hematology analyzers and flow cytometers, which may not be readily available in POC settings. This technology builds upon previous POC devices for electronic cell quantification from whole blood samples.52,73,74 A microfluidic CD64 quantification device demonstrated an AUROC of 0.77, outperforming a subset of SIRS parameters in diagnostic accuracy.72 Cell capture and quantification technologies on chips have broad applications beyond sepsis and are reviewed in detail elsewhere.75–77

Figure 3. Microfluidic Devices for Leukocyte-Based Sepsis Diagnosis

Neutrophil motility, another intrinsic property, is altered during infection and can serve as a diagnostic indicator. Neutrophils isolated from septic patients exhibit a distinctive spontaneous migration pattern.61 A microfluidic assay capitalizing on this principle has been developed for POC sepsis diagnosis (Figure 3B).9 This assay uses continuous fluorescent imaging and machine learning algorithms to quantify neutrophil migration parameters, such as reverse migration, oscillation, and pauses, from a fingerprick blood sample. The assay is automated, requires minimal sample handling, and is robust. While the assay involves a four-hour time-lapse microscopy step followed by a 2.5-hour image processing time, it remains clinically relevant and has demonstrated exceptional diagnostic performance in a double-blinded clinical trial using SOFA scoring as the reference standard. The device achieved an AUROC of 0.99 with 97% sensitivity and 98% specificity, highlighting the potential of neutrophil motility as a highly accurate sepsis biomarker.9

Despite the advancements in blood plasma protein and leukocyte-based POC assays, a POC technology that simultaneously achieves high sensitivity and specificity (above 90th percentile) with a rapid turnaround time (under one hour) remains a key goal in sepsis diagnostics.

Pathogen Isolation and Detection: Point-of-Care Approaches for Targeted Sepsis Therapy

Direct pathogen isolation and detection from blood at the point of care offer a transformative approach for sepsis diagnosis and targeted therapy. Advances in miniaturization and lab-on-a-chip technologies have enabled the development of microfluidic devices for pathogen isolation, lysis, and DNA extraction. These devices can facilitate rapid pathogen identification and guide antibiotic selection, crucial for effective sepsis management. Techniques like dielectrophoresis, inertial effects, surface acoustic waves, and centrifugal microfluidics are being employed for separating infectious agents from blood cells within these integrated systems. Lab-on-a-chip platforms combining bacterial separation, cell lysis (chemical or mechanical), and DNA extraction for PCR or sequence-specific capture hold significant promise for rapid POC sepsis diagnostics.78–80

“Artificial spleen” type devices designed for direct pathogen and endotoxin removal from whole blood are being developed for therapeutic applications (Figure 4A). Analogous to dialysis, these devices process whole blood to capture a broad range of infectious agents using various methods, including ligand and antibody-coated magnetic beads,81–85 porous membranes,86 biomimetic cell margination,[87](#R87],88 acoustophoresis,[89](#R89],90 and elasto-inertial-based migration.91 Table 1 summarizes miniaturized pathogen removal devices for sepsis treatment, comparing their pathogen separation rates and removal efficiencies.

Figure 4. Point-of-Care Pathogen Removal Devices for Sepsis Treatment

Magnetic nanoparticles modified with synthetic ligands that bind to both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria have been developed for pathogen capture.84 Mannose-binding lectin (MBL)-coated magnetic nanobeads, which avoid complement activation and coagulation, have also shown efficacy in pathogen removal (Figure 4B,C).82 These MBL-nanobeads have demonstrated processing rates up to 1.25 L/hr of blood and greater than 90% removal of pathogens in rat models. Mutated lysozyme-coated magnetic beads have been used to separate a broad range of bacterial species, including Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), from whole blood.85 Biomimetic microfluidic devices mimicking microcirculatory cell margination offer non-specific removal of pathogens and cellular components, achieving throughputs of ~1–2 L/hr and potentially reaching 100-fold higher throughputs with multiplexing.87 Acoustic microfluidic methods based on size-selective separation of pathogens have also been reported, achieving greater than 80% bacterial separation from whole blood in a label-free manner (Figure 4D, E).89,90

Table 1. State-of-the-Art Point-of-Care Pathogen Removal Devices for Sepsis Treatment

| Group | Device | Targets | Separation method | Sample | Separation Rate | Reported Pathogen Clearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingber80 | Microfluidic | Fungi (C. albicans) | Magnetic separation with antibody coated beads | Whole blood | 20 ml/hr | 80% |

| Kohane84 | Microfluidic | E. coli | MNPs modified with bis-Zn-DPA | Bovine whole blood | 60 ml/hr | 100% |

| Ingber81 | Microfluidic | S. aureus, E. coli | Magnetic beads with engineered human opsonin-MBL | Rat whole blood | 1.25 L/hr | >90% |

| Russom91 | Microfluidic | E. coli | Elasto-inertial microfluidics with viscoelastic effect | Whole blood | 60 μl/hr | 76% |

| Han87 | Microfluidic | E. coli, leukocytes, cytokines | Passive cell migration | Spiked whole blood | 150 ml/hr | 70% |

| Kreiger85 | Manual | Six Gram-positive and two Gram-negative species, MSSA, MRSA | LysE35A-coated beads | Whole blood | N/A | 85% |

| Zhan86 | Microfluidic | E. coli | Porous polycarbonate (PCTE) membrane with 2 um pores | Whole blood | 50 μl/min | 22% |

| Laurell90 | Microfluidic device with acoustic transducer | P. putida | Size based separation using acoustic impedance | Whole blood | 200 μl/min | 80% |

These miniaturized pathogen removal devices hold significant potential for POC sepsis treatment. Improving clearance rates and efficiency is crucial for therapeutic efficacy. While current separation rates are slower than ideal for rapid therapeutic intervention, achieving flow rates closer to 4–5 L/hr, comparable to kidney dialysis machines, is a desirable goal for POC applications. Strategies to achieve this include multiplexing microfluidic devices, utilizing high-affinity target-binding antibodies, and minimizing technological complexity. Combining on-chip DNA extraction with blood cleansing technology could enable pathogen-specific analysis while initiating targeted antibacterial therapies. Although blood cleansing approaches may not address localized infections within organs, they can delay disease progression, providing valuable time for pathogen identification and targeted antibiotic administration, ultimately improving patient survival.

Commercial Point-of-Care Technologies for Sepsis Diagnosis and Treatment

While many POC sepsis technologies are still in research and development, a range of commercial devices are available, spanning from basic blood analyzers to advanced molecular diagnostics and pathogen removal systems. Table 2 provides an overview of commercially available sepsis technologies and evaluates their suitability for POC application. Currently, many commercial sepsis diagnostics rely on microarrays, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or other complex laboratory equipment, limiting their accessibility in resource-constrained POC settings. However, the market is anticipated to shift towards more readily deployable POC sepsis diagnostics in the coming years.

Table 2. Commercially Available Technologies for Sepsis Diagnosis and Treatment

| Device | Company | Technology | Sample | Turnaround time | Sepsis Diagnosis | FDA clearance | Point-of-care? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Analyzers | |||||||

| EPOC® Blood Analysis System | Siemens Healthineers | Blood gas analyzer with room temperature test card | Whole blood | qSOFA scoring | Yes | Portable, 92 ul blood sample | |

| Microbiology Based | |||||||

| Septi-Chek | Becton Dickinson | Blood culture with media | Whole blood | ~38 hr | Pathogen identification | Yes | Requires laboratory equipment |

| Oxiod Signal | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Blood culture with media | Whole blood | 24hr | Pathogen identification | Yes | Requires laboratory equipment |

| Molecular Diagnostic Based | |||||||

| QuickFISH/PNA FISH | AdvanDx | Fluorescence in situ hybridization | Positive blood culture | ~1.5 hr | Pathogen identification | Yes | Requires microarray equipment |

| hemoFISH | Miacom diagnostics | Fluorescence in situ hybridization | Positive blood culture | 0.5 hr | Pathogen identification | Yes | Requires microarray equipment |

| Prove-it / Verigene | Luminex | PCR amplification and array detection | Positive blood culture | 3.5 hr | Pathogen identification | No | Requires PCR equipment |

| FilmArray | Biofire Diagnostics | Real-time PCR | Positive blood culture | 1hr | Pathogen identification | Yes | Requires FilmArray system |

| HYPLEX | BAG | Multiplex PCR with end point detection using an enzyme-linked sandwich assay in a microtiter plate | Positive blood culture | 3 hr | Pathogen identification | No | Requires PCR and complex instrumentation |

| ACCU-PROBE | Gen-probe | Chemiluminescent DNA probes (rRNA) | Positive blood culture | 3 hr | Pathogen identification | No | Requires PCR and complex instrumentation |

| PLEX-ID BAC | Abott | PCR amplification with Electrospray ionization mass spectrometric analysis | Positive blood culture | 6hr | Pathogen identification | No/CE marking | Requires PCR and complex instrumentation |

| Staph SR | Becton Dickinson | Multiplex PCR | Positive blood culture | 3 hr | Pathogen identification | Yes | Requires PCR equipment |

| StaphPlex | Qiagen | PCR amplification and Array detection | Positive blood culture | 5 hr | Pathogen identification | No | Requires PCR and complex instrumentation |

| MALDI-TOF | bioMérieux | Matrix assisted laser desorption | Positive blood culture | 2hr | Pathogen identification | No | Requires complex instrumentation |

| Magicplex | Seegene | Multiplex PCR | Whole blood | 3.5 hr | Pathogen identification | No | Requires PCR equipment |

| SeptiFast | Roche | Multiplex PCR | Whole blood | 6 hr | Pathogen identification | Yes | Requires PCR equipment |

| SepsiTest | Molzym, Germany | PCR and sequencing | Whole blood | 8–12 hr | Pathogen identification | No | Requires PCR and complex instrumentation |

| VYOO | SIRS lab | Multiplex PCR and gel electrophoresis | Whole blood | 8 hr | Pathogen identification | No | Requires PCR equipment |

| Xpert MRSA/SA | Cepheid | Real-time multiplex PCR | Whole blood | 1hr | Pathogen identification | Yes | Requires PCR equipment |

| VAPChip | Eppendorf Array Technologies, Belgium | Multiplex PCR and hybridization | Whole blood | 5–8 hr | Pathogen identification | No | Requires PCR and complex instrumentation |

| DiagCORE | STAT Diagnostics | 48 plex real-time PCR | Whole blood | 0.5 −1.2 hr | Pathogen identification | No/CE marking | Requires PCR equipment |

| T2 Candida | T2 Biosystems, USA | Miniaturized magnetic resonance | Whole blood | 3–5 hr | Pathogen identification | Yes | Requires complex instrumentation |

| Pathogen Removal Devices | |||||||

| Cytosorb | Cytosorb | Removes cytokines with filter | Whole blood | Up to 24 hours a day, for up to 7 consecutive days | Bacterial removal | No/CE marking | Requires extracorporeal equipment with filtration in a hospital |

| LPS Adsorber | Alteco Medical, Sweden | Peptide binding of endotoxin with porous polyethylene matrix | Whole blood | Not available | Bacterial removal | No/CE marking | Requires extracorporeal equipment with filtration in a hospital |

| LPS-binding Toraymyxin device | Spectral Medical | Ionic binding of Polymyxin-B and Lipid A to endotoxin | Whole blood | Recommended dosing: 2 hr hemoperfusion in 24 hr period | Bacterial removal | No/CE marking | Requires extracorporeal equipment with filtration in a hospital |

Traditional bacterial cultures, while the gold standard for pathogen identification, are time-consuming, typically requiring 24 to 48 hours for results. This delay can hinder timely adjustments from broad-spectrum antibiotics to targeted therapies. Molecular diagnostic techniques like PCR and fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) have emerged as faster alternatives for pathogen identification.92–94 While conventional molecular diagnostics can take up to 12 hours, recent advancements have reduced turnaround times to as little as 30 minutes for identifying multiple bacterial species from positive blood culture samples using FISH-based systems. However, these methods often still rely on initial blood culture to amplify bacterial concentrations to detectable levels, which can take 1–3 days. Technologies like Septifast (Roche), DiagCORE (STAT Diagnostics), and T2 Candida panel aim to bypass the blood culture step, enabling more rapid pathogen identification directly from whole blood samples, with turnaround times ranging from 30 minutes to 6 hours. Despite the availability of commercial systems, many are not ideally suited for POC use due to complexity and infrastructure requirements. The ongoing research in POC sepsis technologies aims to bridge this gap by developing rapid and accurate diagnostic tools that can facilitate targeted antibacterial therapies at the point of need.

Commercial biomarker tests for early organ dysfunction and septic shock prediction are also available. Cytokine profiling and PCT tests are being clinically evaluated for molecular fingerprinting of sepsis progression and treatment response.95–98 Novel biomarkers like adrenomedullin, which increases in blood 1–2 days before septic shock, are also being explored.99 Extracorporeal blood filtering devices, such as Cytosorb, LPS Adsorber, and LPS-binding Toraymyxin, are commercially available for cytokine and endotoxin removal in sepsis management. For POC applications, further development and refinement of these commercial devices are needed to achieve both rapid and accurate sepsis diagnosis and treatment monitoring.

Conclusions: The Future of Point-of-Care Sepsis Management

This review has explored the landscape of developing and commercially available point-of-care technologies for sepsis diagnosis and treatment. A central challenge in POC sepsis diagnostics is balancing speed and accuracy. While some rapid devices, like the EPOC Blood Analysis System, offer quick results, they may have limitations in diagnostic comprehensiveness and require further testing. Conversely, highly sensitive assays may involve complex analysis and longer turnaround times.

Research increasingly indicates that relying on single biomarkers for sepsis diagnosis may be insufficient.100 Biomarker panels and multiplexed assays hold greater promise for improving diagnostic accuracy.56–58,101 Pathogen detection in sepsis is also complex due to the diverse range of infectious agents, detection limit challenges, and lengthy culture times. Emerging evidence highlights the potential of immune system markers, particularly neutrophils, as robust indicators of sepsis, reflecting their critical role in innate immunity and rapid response to infection.102 Future research is likely to further emphasize immune response markers in POC sepsis diagnostics.

The concept of sepsis as a homogenous disease entity is being questioned, with growing recognition of sepsis heterogeneity.103–109 Subtypes of sepsis based on functional analysis, immune response states, and genomic profiles have been proposed, suggesting that a universal diagnostic device for all sepsis types may be unrealistic. Personalized approaches, utilizing different diagnostics and treatments for specific sepsis subtypes and stages, may be necessary.100 Further research into sepsis heterogeneity and its implications for diagnostics and therapies is crucial.

The transition to SOFA scoring as the sepsis diagnostic standard presents challenges for benchmarking POC diagnostic devices. Establishing standardized protocols for comparing POC devices against SOFA and other relevant benchmarks is essential for advancing the field. Future POC sepsis diagnostics should prioritize affordability, long-term stability, and the integration of diagnostic outcomes with treatment decisions. Expanding diagnostic capabilities to differentiate sepsis stages and progression, beyond a binary septic/non-septic classification, is also a key direction. Point-of-care technologies for sepsis diagnosis and treatment hold immense potential to improve healthcare access, save lives, reduce healthcare costs, and alleviate patient suffering globally, particularly in resource-limited settings. Significant progress has been made in the past decade, yet continued research and development are vital to realize the full potential of POC technologies in combating sepsis.

Acknowledgements

DE acknowledges support from the US National Institutes of Health through grant R01EB021331 (FeverPhone). AS acknowledges support from the US National Institutes of Health through grant R01AI132738-01A1.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.