Introduction

Bias, defined as a predisposition for or against an idea, person, or group, can manifest consciously or unconsciously. Unconscious or implicit bias, where individuals are unaware of their evaluations, is particularly concerning in sensitive fields like healthcare, especially concerning mental health during pregnancy. While explicit bias involves conscious awareness of these evaluations, implicit biases operate subtly, influencing clinical consultations and decision-making, often outside the realm of explicit clinical reasoning but widely recognized in business and other sectors.[1,2,3,4] The lack of awareness surrounding implicit bias in mental health care during pregnancy can perpetuate disparities, potentially affecting diagnosis, treatment, and ultimately, maternal wellbeing.

Cognitive biases, systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, can further complicate mental health care during pregnancy. For instance, framing bias might lead clinicians to prioritize certain interventions over others based on how information is presented. Action bias could manifest as the inclination to prescribe medication even with limited evidence, driven by the urgency to act during pregnancy. Conversely, present bias might result in prioritizing immediate concerns over long-term mental health strategies for expectant mothers.[7,8] The novelty of individual cases and the evolving understanding of mental health during pregnancy, coupled with the pressures of time and resources, can amplify the impact of cognitive biases. Furthermore, readily available but not critically evaluated information, amplified by media or personal beliefs, might lead to availability bias, influencing diagnostic and treatment decisions.[8,10] The emotional and physical stress inherent in pregnancy and healthcare settings can exacerbate these biases, impacting the objectivity of mental health assessments.

This article aims to explore the potential influence of bias on mental health care during pregnancy, focusing on diagnostic processes and the broader implications for maternal wellbeing. We will examine how biases can affect clinical practice, research, and decision-making in this specific context, and discuss potential strategies to mitigate these biases and improve the quality of mental health care for pregnant individuals.

Methods

This article employs a non-systematic literature review approach, acknowledging the diverse and complex nature of bias research in healthcare, particularly concerning mental health during pregnancy. A systematic review methodology may not be suitable given the heterogeneity of study designs and the multifaceted nature of the topic. The review included English language articles identified through searches of PubMed and Cochrane databases from January 1957 to December 2023, using search terms such as ‘implicit bias’, ‘unconscious bias’, ‘cognitive bias’, ‘diagnostic error and bias’, ‘pregnancy’, and ‘maternal mental health’. Priority was given to high-level evidence, including recent systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and literature reviews. Opinion articles were incorporated in the introduction and discussion sections to provide context and suggest potential future directions. Articles focusing on bias modification in specific clinical psychiatry settings were excluded if they did not contribute to a broader understanding of bias in mental health care during pregnancy.

The Mechanisms and Origins of Bias

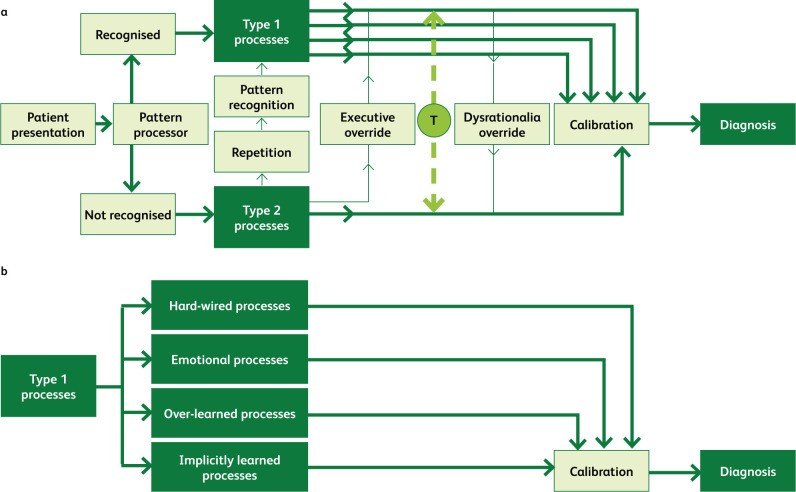

Decision-making, including diagnostic processes in mental health care during pregnancy, can be understood through the dual process theory (DPT), involving type 1 and type 2 processes (Fig. 1).[12,13] Type 1 processes are rapid, unconscious, intuitive, and require minimal cognitive effort, often acting as mental shortcuts or heuristics for quick decisions.[13,14] In contrast, type 2 processes are slower, conscious, analytical, and demand more cognitive resources.[13] Type 1 processing dominates decision-making and is more susceptible to errors, which, when repeated, can lead to systematic biases. These automatic decisions, while necessary for efficient functioning, can be prone to biases formed early in life through social stereotypes, personal experiences, and the experiences of those around us.[15] Recognizing these origins is crucial in understanding how biases might influence mental health diagnoses during pregnancy.

Fig 1.

Decision-making processes relevant to mental health diagnosis during pregnancy. a) Interaction between type 1 and type 2 processes in diagnosing mental health conditions during prenatal and postnatal care. T = ‘toggle function’; the ability to switch between type 1 and type 2 processes. b) Type 1 processes controlling calibration of decision making in mental health diagnosis during pregnancy. Adapted with permission from Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 1: origins of bias and theory of debiasing. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22(Suppl 2):ii58–64.

The Implicit Association Test (IAT) is frequently used in research to measure bias. It assesses unconscious associations by measuring reaction times to categorize words into groups, covering various biases, including gender and race.[16,17] For instance, in a gender-related IAT, participants might sort words related to ‘family’ or ‘career’ with ‘male’ or ‘female’ names. Meta-analyses have examined the IAT’s effectiveness in predicting social behavior.[18,19] However, critics question the IAT’s validity, arguing it may not accurately differentiate between associations and automatic responses.[20] Ethical concerns also exist regarding its potential misuse as a predictive tool for prejudice or discrimination.[22] Despite these limitations, the IAT can serve as a tool for self-reflection and awareness of potential biases in mental health care, rather than a definitive measure of prejudice.[23] It is essential to consider systemic factors alongside individual biases.

Research using IAT in healthcare reveals that professionals often exhibit negative biases towards certain groups, including racial and ethnic minorities.[24,25] These biases can significantly impact treatment decisions and patient outcomes. In the context of mental health during pregnancy, biases related to race, socioeconomic status, or pre-existing conditions could influence how clinicians perceive and diagnose mental health issues in expectant mothers, potentially leading to disparities in care.

Bias in Clinical Mental Health Care During Pregnancy

Weight bias, or prejudice against overweight or obese individuals, is prevalent among healthcare professionals, including those involved in maternal care.[27–29] This bias may stem from inadequate education on the complexities of obesity and insensitive consultation approaches.[30–32] During pregnancy, weight bias could influence the assessment of mental health, with clinicians potentially attributing symptoms to weight rather than considering underlying mental health conditions.

Gender bias also manifests in healthcare settings. Female doctors may be misidentified as nurses, and female leaders may be under-recognized compared to their male counterparts.[34,35] In mental health care during pregnancy, gender biases could affect the perception of female patients’ emotional and psychological needs. For example, symptoms of postpartum depression in women might be dismissed or underestimated due to gender stereotypes or biases about maternal roles and emotional expression.

Racial and ethnic disparities are significant concerns in maternal healthcare. Reports indicate higher maternal mortality rates among Black women compared to White women, suggesting systemic inequities and biases within the healthcare system.[45,46] These disparities likely extend to mental health care during pregnancy, where biases related to race and ethnicity can influence diagnosis and treatment. Cultural competence training and models emphasizing ‘cultural safety’ are crucial to challenge biases and improve healthcare equity.[49,50,51] In mental health, understanding cultural nuances and addressing biases is vital for accurate diagnosis and culturally sensitive care during pregnancy and postpartum.

Concerning specific diagnostic biases in maternal mental health, consider the following:

- Anchoring Bias: In prenatal mental health screenings, if initial information suggests a patient is coping well (e.g., reporting excitement about the pregnancy), a clinician might anchor on this positive initial assessment and underemphasize later-reported anxieties or depressive symptoms.

- Availability Bias: A recent case of severe postpartum psychosis might make clinicians more likely to diagnose postpartum psychosis in subsequent patients presenting with any mood changes after delivery, even if other diagnoses are more probable.

- Confirmation Bias: If a clinician suspects a pregnant patient with a history of anxiety is simply experiencing ‘pregnancy-related anxiety’, they might selectively focus on information confirming this, overlooking symptoms that suggest a more serious anxiety disorder or depression.

- Affective Bias: A clinician’s personal feelings about a patient (positive or negative, potentially based on perceived compliance or demeanor) could influence their diagnosis. For example, a clinician might be less thorough in assessing mental health in a patient they perceive as ‘demanding’ or ‘uncooperative’.

These biases can lead to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis of mental health conditions during pregnancy, impacting maternal wellbeing and potentially leading to adverse outcomes for both mother and child.

Bias in Research, Evidence Synthesis, and Policy Relevant to Maternal Mental Health

Research and policy in healthcare, including maternal mental health, are not immune to bias.[52] Research priorities, funding, and interpretation of findings can be shaped by cultural and institutional biases. For instance, research focusing on pharmacological interventions for postpartum depression might be favored over studies on psychosocial support or preventative strategies due to funding biases or prevalent medical models.

Gender bias in research can disadvantage women researchers and influence the types of research questions asked and answered.[55,56] In maternal mental health research, this could manifest as underrepresentation of female researchers or a focus on areas that align with traditional gender roles, potentially neglecting important aspects of women’s mental health experiences during and after pregnancy.

Geographic bias, favoring research from high-income countries, can also limit the evidence base for maternal mental health interventions, particularly in diverse populations and low-resource settings.[61,62,63] This bias can lead to the neglect of valuable data and insights from low-income countries, hindering the development of universally applicable and culturally appropriate mental health care models for pregnant women.

In evidence-based policy (EBP) and guideline development for maternal mental health, both technical and issue biases can arise.[67] Technical bias might occur when policymakers selectively use evidence to support a preferred policy, while issue bias can arise when the framing of evidence directs political debate in a specific direction, potentially overlooking comprehensive or balanced approaches to maternal mental health care.

Cognitive Biases and Diagnostic Errors in Maternal Mental Health Care

Diagnostic errors are a reality in healthcare, including mental health care during pregnancy.[68,69,70] Cognitive biases are significant contributors to these errors, intertwined with system-related factors and individual limitations.[77,78] Various cognitive biases can impact diagnostic accuracy in maternal mental health (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected cognitive biases in maternal mental health care during pregnancy with definitions and examples in the context of diagnosing depression during pregnancy. [79–86]

| Type of bias | Definition | Practical example in Pregnancy Mental Health |

|---|---|---|

| Affective or visceral bias | Clinician’s feelings towards a pregnant patient lead to misdiagnosis. | A clinician, feeling impatient with a pregnant patient who is tearful and anxious, attributes her symptoms to ‘hormones’ without thoroughly assessing for prenatal depression. |

| Anchoring bias | Over-reliance on initial information, hindering adjustment to new information. | Upon learning a pregnant patient is a first-time mother, a clinician anchors on ‘normal first-pregnancy anxieties’ and overlooks indicators of clinical depression that emerge later in the consultation. |

| Premature closure | Ending diagnostic process too early, before full assessment. | A clinician diagnoses ‘adjustment issues’ in a pregnant patient presenting with sleep disturbance and fatigue, prematurely closing the assessment without exploring other depressive symptoms or considering formal diagnostic criteria for depression. |

| Availability bias | Overemphasizing recently encountered diagnoses, or underemphasizing less frequent ones. | After recently managing a case of severe postpartum depression, a clinician might over-diagnose depression in subsequent pregnant patients with milder mood symptoms, due to heightened awareness of depressive disorders. |

| Confirmation bias | Seeking information that confirms a favored diagnosis, ignoring contradictory data. | Suspecting ‘pregnancy blues’ in a patient reporting low mood, a clinician focuses on questions about hormonal changes and dismisses patient reports of persistent sadness and loss of interest in activities, which could indicate depression. |

| Commission (action) bias | Favoring action over inaction, believing ‘more is better’. | Concerned about undiagnosed depression, a clinician might start a pregnant patient on antidepressants based on borderline symptoms, even when watchful waiting and psychosocial support might be more appropriate initial steps. |

| Omission (inaction) bias | Favoring inaction over action, believing ‘less is better’. | A clinician might hesitate to diagnose or treat prenatal depression, fearing medication risks during pregnancy, even when the risks of untreated depression outweigh potential medication risks. |

| Diagnostic momentum | Reinforcing a diagnosis initially suggested, even when evidence contradicts it. | If a previous healthcare provider labeled a pregnant patient as ‘emotionally labile’, subsequent clinicians might continue to view her symptoms through this lens, overlooking new symptoms indicative of a mental health disorder. |

| Gambler’s fallacy | Belief that a condition is less likely after repeated diagnoses of it. | Having diagnosed several pregnant patients with depression recently, a clinician might underestimate the likelihood of depression in the next pregnant patient presenting with similar symptoms, believing ‘it can’t be depression again’. |

| Overconfidence bias | Overestimating one’s diagnostic abilities, relying on intuition over objective data. | A clinician, confident in their ‘clinical intuition’, might diagnose ‘situational stress’ in a pregnant patient based on a brief interaction, without using standardized screening tools or conducting a thorough mental health assessment. |

| Sutton’s slip or law | Focusing on the most obvious diagnosis, neglecting less common but possible ones. | In a pregnant patient presenting with anxiety, a clinician might immediately diagnose ‘generalized anxiety disorder’ (common) without considering less frequent but relevant diagnoses like ‘obsessive-compulsive disorder’ or ‘panic disorder’ which may have specific implications for pregnancy. |

| Hindsight bias | Believing a diagnosis was more predictable after it is known. | After a pregnant patient develops severe postpartum depression that was missed during prenatal care, clinicians might retrospectively believe the prenatal symptoms were ‘obvious signs’ of impending postpartum depression, even if those symptoms were subtle or ambiguous at the time. |

Evidence-Based Bias Training and Mitigation in Maternal Mental Health

Diagnostic decision-making relies on both type 1 and type 2 processes, as per DPT.[87] However, ‘thinking slow’ (type 2) is not always superior to ‘thinking fast’ (type 1) in clinical settings.[12,88,89,90] Strategies like reflection and cognitive forcing, and debiasing checklists, have shown limited effectiveness in reducing bias and diagnostic errors.[91,92,93,94] Clinicians may disagree on the specific cognitive biases involved in diagnostic errors, highlighting the complexity of bias recognition and mitigation.[95]

Systematic reviews of interventions targeting DPT in medical education show mixed results in reducing diagnostic error rates.[70] Many studies have small sample sizes and methodological differences, contributing to the inconsistent evidence base.[96] This suggests that reducing bias is a complex, multifaceted challenge, particularly in the context of mental health care during pregnancy. Checklists and structured approaches can aid clinicians in making better decisions and mitigating biases (Box 1).[97,98,99] Given the ‘wicked’ nature of bias, unconventional teaching methods, such as case conferences focusing on health equity and implicit bias, and transformative learning theory, may be beneficial.[65,100,101,102] Transformative learning, integrating experience, reflection, discussion, and simulation, aligns with principles of Balint groups and comprehensive bias reduction strategies.[102,103]

Box 1.

Suggested checklist for making sound clinical decisions in maternal mental health care.[97–99]

| In assessing a pregnant patient’s mental health: Are the data truly relevant, or just salient based on stereotypes or assumptions? Have I considered diagnoses beyond the most obvious ones? How did I arrive at this diagnosis? Was it suggested by a colleague or influenced by the patient’s presentation? Have I asked questions to disprove, rather than confirm, my initial hypothesis? Have I been distracted or interrupted during the assessment? Do I have any personal biases (like or dislike) towards this patient that might affect my judgment? Am I stereotyping this patient based on her background, age, or other factors? Remember, diagnostic certainty can be misleading; consider alternative diagnoses. |

|---|

Hagiwara et al. identify translational gaps hindering bias training effectiveness in healthcare.[104] These include: lack of motivation assessment for change, absence of clear mitigation strategies, and insufficient communication training alongside bias training. Effective bias training should address motivation, provide concrete strategies, and integrate communication skills, including awareness of micro-aggressions in verbal and non-verbal communication.[105]

Discussion

Evidence supporting reflective practice as a definitive strategy to reduce clinician bias is limited. However, tools like cultural safety checklists and decision-making checklists (Box 1) can support clinicians in practice.[97,98,99] Increased awareness of biases in clinical reasoning can help reduce diagnostic errors and improve patient safety, particularly for marginalized groups who often experience poorer healthcare outcomes.[106,107] Bias training aims to bridge the gap between unawareness and recognition of bias, fostering mitigation of personal biases and identification of systemic discrimination.[108] Self-reflection, asking ‘Would I treat this patient differently if they were different in terms of race, age, socioeconomic status, etc.?’ is a crucial step in personal accountability.

Despite the potential benefits of bias training in raising awareness, effective debiasing strategies remain limited.[109] Integrating bias training into clinical specialty training, rather than as an isolated topic, is suggested.[110] Combining bias training with motivation enhancement, communication skills development, and evidence-based mitigation strategies may increase effectiveness.[101] IAT testing, if used, should be applied cautiously, focusing on self-reflection rather than punitive assessment.

Organizations should consider incorporating bias training into undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula, given the growing recognition of bias impact and the lack of proven debiasing methods. The Royal College of Surgeons of England has acknowledged the importance of unconscious bias, indicating increasing institutional awareness.[111] More robust research is needed to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of bias reduction strategies.

In our increasingly data-driven world, the impact of bias is amplified.[112] Algorithmic bias, as seen in examples like step-counting apps that undercount steps for certain demographics, highlights the need for diverse data and algorithm development.[113,114,115] In artificial intelligence and healthcare algorithms used in maternal mental health, rigorous testing across diverse populations and diverse development teams are essential to minimize bias and enhance applicability.

The Black Lives Matter movement has heightened awareness of systemic racism, prompting institutions to consider bias training.[116,117] However, implicit bias awareness and training should not overshadow broader socio-economic, political, and structural barriers contributing to healthcare disparities. Implicit bias awareness must not excuse explicit prejudice or systemic inequities.[117] Addressing the lack of representation of diverse populations in research and medical resources is crucial.[118,119,120] Challenging the role of race in clinical algorithms and guidelines is also essential.[121,122] Racial bias in medical devices, such as pulse oximetry, further underscores the need for vigilance against bias in all aspects of healthcare.[123]

In maternal mental health systems, understanding personal bias can inform recruitment processes and promote diverse leadership and workforce representation, better reflecting the populations served.[124] This can contribute to improved patient outcomes and more equitable care. Strategies to reduce bias in recruitment and management include objective criteria, blinded evaluations, and salary transparency.[125] Establishing mechanisms for reporting discrimination, monitoring outcomes related to pay and hiring, and regularly assessing employee perceptions of inclusion and fairness are also vital steps toward mitigating inequality and promoting equity in maternal mental health care.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof Damien Ridge for his insightful suggestions on this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Dipesh Gopal is an in-practice fellow supported by the Department of Health and Social Care and the National Institute for Health Research.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

No honoraria paid to promote media cited including books, podcasts and websites.