Severe mental illness (SMI) encompasses a range of psychological disorders that significantly impair an individual’s ability to perform daily functions and occupational tasks. Conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are commonly classified as SMIs. It’s widely recognized that individuals with SMI experience poorer physical health outcomes compared to the general population. This report delves into the prevalence of physical health conditions among people with SMI in England, aiming to quantify and understand the health inequalities they face. By analyzing a substantial dataset of general practice records, this study seeks to inform strategies and interventions to reduce premature mortality and improve the overall health of individuals living with SMI.

This analysis is crucial for:

- National bodies responsible for shaping strategy, policy, and guidelines concerning individuals with SMI.

- Local healthcare organizations involved in planning, managing, and delivering both preventative and clinical care for this population.

- Organizations that handle the integrated management and treatment of both mental and physical health conditions in individuals with SMI.

This report contributes to the broader public health agenda of reducing mortality gaps and health disparities experienced by those with mental health challenges, spearheaded by Public Health England (PHE).

Background and Methodology

It is a well-established fact that individuals with SMI are disproportionately affected by poor physical health, leading to higher rates of premature death compared to the general population. Statistics for people with SMI in England reveal concerning trends:

- They are more than twice as likely to have diabetes.

- They are twice as likely to suffer from hypertension.

- They are significantly more prone to obesity.

- They experience a higher incidence of asthma.

- They have elevated rates of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, and heart failure (HF).

- They face a greater risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Their risk of cancer is comparable to the general population, yet they often experience poorer outcomes.

Alarmingly, it’s estimated that preventable physical illnesses account for two out of every three deaths among individuals with SMI. Major contributors to mortality include chronic physical conditions such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory ailments, diabetes, and hypertension.

Compared to the general population, individuals under 75 years of age in contact with mental health services in England face significantly elevated death rates:

- Liver disease: 5 times higher

- Respiratory disease: 4.7 times higher

- Cardiovascular disease: 3.3 times higher

- Cancer: 2 times higher

The disparity in death rates is stark, with substantial excess deaths per 100,000 population in adults with SMI compared to the general population across these conditions. Addressing cardiovascular disease mortality holds the greatest potential to impact the largest number of individuals within this vulnerable group.

Beyond chronic physical health conditions, suicide remains a significant cause of mortality in the SMI population, particularly following acute psychotic episodes and psychiatric hospitalization. Other contributing factors to mortality include substance abuse, Parkinson’s disease, accidents, dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease), and infections, notably pneumonia.

Organizations like the Disability Rights Commission have long advocated for governmental action to address these profound health inequalities. The NHS Five Year Forward View for Mental Health has underscored the urgent need to address the physical health needs of individuals with SMI as a critical step in mitigating these disparities. Collaborative efforts from leading medical royal colleges and Public Health England have outlined essential actions to enhance the physical health of adults with SMI across the NHS. A deeper understanding of the physical health needs of individuals with SMI within general practice settings is essential for designing effective interventions aimed at reducing premature deaths and health inequalities.

This report leverages data from The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database (May 2018), a large general practice database, to investigate:

- The prevalence of SMI in England, categorized by age, sex, and socioeconomic deprivation.

- The proportion of individuals with SMI who also experience co-morbidities and multi-morbidities.

- Disparities in co-morbidities and multi-morbidities between the SMI population and the general population in England, considering age, sex, and deprivation.

The analysis is conducted at the national level for England, as sub-national geographical breakdowns are not available within the THIN database.

The definitions of SMI and physical conditions are aligned with the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) guidelines, utilizing diagnostic criteria. Medication prescribing criteria were intentionally excluded to streamline data extraction and analysis replication. The physical conditions under scrutiny in this analysis include:

- Asthma

- Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

- Cancer

- Coronary Heart Disease (CHD)

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

- Diabetes

- Heart Failure (HF)

- Hypertension

- Obesity

- Stroke

Liver disease is not included due to its absence from QOF recording.

Statistical significance is determined using 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Differences in prevalence are deemed significant if their 95% CIs do not overlap. Prevalence rates for the entire patient population serve as reference points without CIs. Rate ratios, calculated by dividing the prevalence in SMI patients by the prevalence in all patients, are used to quantify the level of health inequality. A rate ratio exceeding one indicates a higher prevalence among SMI patients.

Data visualization and presentation in this report adhere to the following conventions:

- Consistent condition order across all charts, ordered from highest to lowest prevalence in the THIN patient population.

- Age stratification into three groups: 15-34, 35-54, and 55-74 years.

- Deprivation quintiles, dividing the population into five equal groups based on socioeconomic deprivation.

- Uniform y-axis scales across charts displaying physical health condition prevalence, where feasible for clarity.

- Variable y-axis scales when necessary for data clarity, clearly indicated on the chart.

- Visual representation of 95% CIs in charts, with detailed keys provided.

- Rate ratios displayed above chart bars, with bolding to denote statistically significant higher prevalence in SMI patients.

Terminology used throughout the report is consistent:

- ‘All patients’ refers to all patients aged 15 to 74 in THIN, inclusive of patients with SMI.

- ‘SMI patients’ refers specifically to patients aged 15 to 74 in THIN with a diagnosed SMI.

The term ‘people with SMI’ is generally used when referencing prior research and existing evidence.

Detailed methodological information, including strengths and limitations, can be found in PHE’s ‘Technical supplement: severe mental illness and physical health inequalities’. Comprehensive data tables are also available in this technical supplement.

Key Findings

The findings of this analysis corroborate previous research and provide new evidence concerning the physical health disparities experienced by individuals with SMI compared to the general population. Key findings are summarized below:

- Elevated Prevalence of Several Conditions: SMI patients exhibit a higher prevalence of obesity, asthma, diabetes, COPD, CHD, stroke, and HF compared to all patients. The prevalence of hypertension, cancer, and AF is similar between the two groups.

- Age-Related Disparities: Health inequalities are more pronounced in younger age groups, with the most significant disparities in the 15-34 age range for asthma, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.

- Higher Comorbidity Rates: SMI patients are more likely to have one or more physical health conditions (1.3 times for females and 1.2 times for males) compared to all patients.

- Increased Multi-morbidity: The health inequality gap between SMI and all patients nearly doubles when considering multi-morbidity (two or more physical health conditions).

- Multi-morbidity in Younger Adults: SMI patients aged 15-34 are five times more likely to have three or more physical health conditions, with this inequality diminishing with age.

- Deprivation and SMI Prevalence: Patients residing in more deprived areas exhibit a higher prevalence of SMI.

- Deprivation and Physical Health in SMI: SMI patients in more deprived areas also experience a higher prevalence of physical health conditions.

- Persistent Inequalities After Adjustment: Even after accounting for deprivation, age, and sex, SMI patients continue to experience significant health inequalities in obesity, asthma, diabetes, COPD, CHD, and stroke.

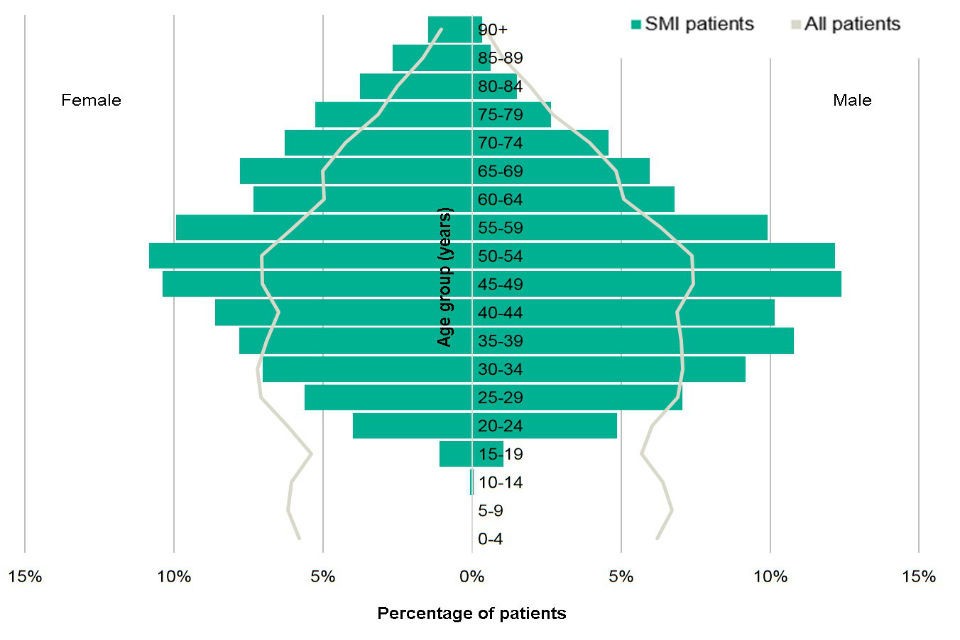

SMI Prevalence

Demographics, encompassing the statistical characteristics of populations, reveal that the SMI patient population in THIN exhibits a different demographic structure compared to the general patient population (Figure 1). Key differences include:

- Fewer SMI patients in the youngest age groups (0-14 years).

- Higher proportions of males with SMI between 30 and 74 years.

- Higher proportions of females with SMI from age 35 onwards.

These demographic variations emphasize the importance of age standardization for meaningful comparisons between SMI and all patients. Standardization is a statistical technique used to adjust rates, such as disease or death rates, to account for differences in population structures, ensuring valid comparisons across different groups.

Figure 1: Age (years) and sex distribution of patients with a diagnosis of severe mental illness (SMI) compared with all THIN patients

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018

Out of 1,051,127 patients aged 15-74 in THIN, 9,357 (0.9%) had an SMI diagnosis. The QOF SMI register reports a similar prevalence of 0.9% for the period April 2016 to March 2017 across all ages. The slightly lower SMI prevalence in THIN (0.7% for all ages) compared to QOF may be partially attributed to the exclusion of lithium prescribing criteria in the THIN analysis and potential differences in the age structures of the THIN and QOF populations. Further details on these discrepancies are available in PHE’s ‘Technical supplement: severe mental illness and physical health inequalities’.

Figure 2: Prevalence of severe mental illness (SMI) in patients aged 15 to 74 by sex, age group and deprivation

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018

Analysis of SMI prevalence within the SMI patient group (Figure 2) reveals higher proportions among:

- Males (0.9%) compared to females (0.8%).

- Individuals aged 35-74 (1.1%) compared to those aged 15-34 (0.6%).

- Patients residing in the most deprived areas (1.8%) compared to the least deprived areas (0.5%).

Further variations may exist between males and females in SMI diagnosis based on condition type and age within the THIN dataset. Previous research on the initial recording of SMI diagnoses in UK primary care indicates:

- Schizophrenia diagnosis is more frequent in men than women.

- Schizophrenia diagnosis in men is more common between 16 and 24 years, whereas in women, it is consistent across all ages.

- Bipolar disorder diagnosis is more frequent in women than men.

- Bipolar disorder diagnosis in men is more common between 35 and 44 years, while in women, the most common ages are 25 to 34.

- Other psychosis diagnoses are more frequent in men than women.

- Other psychosis diagnoses in men are most common between 16 and 24 years, whereas in women, the most common ages are over 75 years.

These findings align with prior research showing a higher prevalence of SMI in more deprived areas. Socioeconomic deprivation factors, such as social stress and poverty, are recognized as both causes and consequences of SMI. Social mobility, the ability to move up or down in socioeconomic status, is often negatively impacted for individuals with SMI, leading to a downward trend in socioeconomic status compared to the general population. This downward socioeconomic drift commonly results in unemployment and social exclusion, with a heightened risk observed in men and a marked decline from parental social status in younger age groups. Consequently, individuals with SMI face a significant risk of social drop-out, encompassing withdrawal from competition, education, employment, daily activities, and mainstream society.

SMI and Physical Health Conditions

The prevalence of physical health conditions within the SMI population in THIN is broadly consistent with England QOF prevalence data for April 2016 to March 2017. Prevalence figures from this analysis are:

- Within 0.5 percentage points of QOF values for diabetes, COPD, CHD, AF, cancer, stroke, and HF.

- 1.4 percentage points higher than QOF for hypertension.

- 2.2 percentage points higher than QOF for obesity.

- 3 percentage points higher than QOF for asthma.

More detailed comparisons are available in PHE’s ‘Technical supplement: severe mental illness and physical health inequalities’.

This analysis confirms that patients with SMI experience poorer physical health compared to all patients (Figure 3). Rate ratios, indicating the disparity in prevalence between SMI and all patients, are shown above the chart bars, with statistically significant higher prevalence for SMI patients highlighted in bold.

Figure 3: Prevalence (age and sex standardized) of physical health conditions for severe mental illness (SMI) and all patients aged 15 to 74

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018 Key: atrial fibrillation (AF), coronary heart disease (CHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure (HF)

SMI patients exhibit a higher prevalence for 7 of the 10 physical health conditions examined. The degree of health inequality varies across conditions (Figure 3). The highest rate ratios between SMI and all patients are observed for:

- Obesity (1.8 times higher in SMI)

- Asthma (1.2 times higher in SMI)

- Diabetes (1.9 times higher in SMI)

- COPD (2.1 times higher in SMI)

- CHD (1.2 times higher in SMI)

- Stroke (1.6 times higher in SMI)

- HF (1.5 times higher in SMI)

Tobacco use, a major risk factor for CHD, COPD, HF, and stroke, and elevated smoking rates within the SMI population may partially explain the higher prevalence of these conditions. However, smoking is also a risk factor for hypertension and cancer, conditions not showing notably higher prevalence in people with SMI overall in this analysis.

These findings are consistent with existing research documenting poorer physical health among individuals with SMI, particularly highlighting elevated risks of diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, and respiratory illnesses. These conditions are often influenced by health behaviors such as smoking, poor diet, and substance misuse.

While overall hypertension prevalence is similar between SMI and all patients, it remains a significant co-morbidity for people with SMI due to its high prevalence. Notably, younger SMI patients show a much higher prevalence of hypertension compared to their all-patient counterparts (Figure 4), underscoring the importance of early intervention for cardiovascular risk management in this population.

Cancer prevalence is similar overall in SMI and all patients. However, mixed evidence exists in literature, with some studies reporting higher prevalence in SMI populations. Given the shorter life expectancy of people with SMI, they may die from other causes before reaching typical ages of cancer diagnosis. Furthermore, analyzing all cancers collectively may mask disparities in specific cancer types and associated risk factors, such as lung cancer and smoking.

Cancer prevalence alone may not fully capture health inequality. People with SMI experience higher cancer case fatality rates and lower cancer survival rates, contributing to excess premature mortality. Socio-demographic factors influence cancer treatment, and patient choice plays a crucial role in treatment outcomes. Factors related to diagnosis, disease progression, and treatment are likely contributors to the health inequalities experienced by individuals with both SMI and cancer.

Physical Health Conditions by Age

Age-stratified analysis was robustly conducted for asthma, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, conditions with sufficient SMI patient numbers in each age group (10 or more).

Compared to all patients, SMI patients (Figure 4) demonstrate a higher prevalence of:

- Obesity and diabetes across all age groups.

- Asthma and hypertension in the 15-34 and 35-54 age groups.

Although obesity prevalence in SMI patients is higher than in all patients, THIN-based proportions are lower than the 26% adult obesity rate reported in the Health Survey for England (2016). This suggests potential underestimation of obesity prevalence in both THIN and QOF data, implying that the actual health inequality between SMI and all patients may be even greater.

Figure 4: Age-specific prevalence of physical health conditions for severe mental illness (SMI) patients and all patients aged 15 to 74

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018 Note: change in y-axis scale to allow clear presentation; COPD, cancer, CHD, stroke, AF and HF were not included in the analysis due an insufficient number of patients in each age group to carry out a robust analysis

Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension increases with age in both SMI and all patients, while asthma prevalence decreases. However, for all four conditions, the level of health inequality between SMI and all patients is higher in younger age groups. Compared to all patients, SMI patients are:

- 3.0 times more likely to be obese in the 15-34 age group, but only 1.6 times more likely in the 55-74 age group.

- 1.3 times more likely to have asthma in the 15-34 and 35-54 age groups, with no significant difference in the 55-74 age group.

- 3.2 times more likely to have hypertension in the 15-34 age group, but only 1.3 times more likely in the 35-54 age group.

- 3.7 times more likely to have diabetes in the 15-34 age group, but only 1.6 times more likely in the 55-74 age group.

These age-related findings align with research documenting higher physical health inequality in younger SMI patients. For instance, a London study found a higher risk of type 2 diabetes in younger SMI populations, not fully explained by antipsychotic prescribing, which diminished by age 55. Antipsychotic medications, linked to metabolic side effects, may contribute to the higher prevalence of obesity, diabetes, CHD, and HF in SMI patients. Metabolic side effects can include weight gain, high blood sugar, blood pressure, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels.

Mortality rate inequalities are most pronounced in the 30-44 age group, where SMI patients experience death rates approximately five times higher than the general population. Given the shorter life expectancy of people with SMI, the reduced health inequality in older age groups may be partially due to this factor. This report underscores the necessity for:

- Early physical health assessments for people with SMI.

- Early interventions to mitigate the impact of existing poor physical health.

- Early care pathway planning focused on physical health improvement for people with SMI.

Physical Health Conditions by Sex

After age standardization, notable sex-based differences in physical health condition prevalence within SMI patients (Figure 5) include:

- Higher obesity in females (13.9%) than males (11.7%).

- Higher asthma in females (13.9%) than males (10.8%).

- Higher cancer in females (2.9%) than males (1.9%).

- Higher CHD in males (3.5%) than females (1.4%).

- Higher AF in males (1.2%) than females (0.5%).

Prevalence of other physical health conditions is similar between males and females.

Figure 5: Prevalence (age standardised) of physical health conditions by sex for severe mental illness (SMI) and all patients aged 15 to 74

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018 Key: atrial fibrillation (AF), coronary heart disease (CHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure (HF)

Rate ratios of physical health condition prevalence between SMI and all patients are similar across sexes, consistent with excess mortality data showing similarly elevated premature mortality rates in both males and females with SMI.

Physical Health Conditions by Deprivation

Deprivation quintile analysis was robustly conducted for obesity, asthma, hypertension, diabetes, COPD, CHD, cancer, and stroke, conditions with sufficient SMI patient numbers (100 or more). Townsend deprivation scores were used as the available deprivation measure in THIN. Broader age groups (15-34, 35-54, 55-74) were used for deprivation analysis to ensure sufficient patient numbers and standardization robustness.

Figures 6 and 7 present findings for obesity, asthma, hypertension, diabetes, COPD, cancer, CHD, and stroke by deprivation quintile. Prevalence data by deprivation quintile is based on smaller patient groups, leading to greater variability and wider confidence intervals. Some apparent differences may be due to chance rather than statistical significance and should be interpreted cautiously.

After age and sex standardization, physical health condition prevalence (Figures 6 and 7) remains higher in SMI patients compared to all patients for:

- Asthma in the most deprived areas (14.2%) compared to the least deprived (9.6%).

- Diabetes in the most deprived areas (12.2%) compared to the least deprived (8.0%).

- COPD in the most deprived areas (3.1%) compared to the least deprived (1.3%).

- Cancer in the least deprived areas (3.7%) compared to the most deprived (1.9%).

Only cancer prevalence shows an inverse gradient with deprivation. While cancer incidence is higher in more deprived areas, cancer prevalence is often higher in less deprived groups due to better survival rates for cancers more common in these groups, such as skin and breast cancers. The analysis compares least and most deprived areas to assess the inequality gap within SMI patients by deprivation, but this method does not account for intermediate deprivation quintiles. Regression analysis including all SMI patients could offer an alternative approach.

Figure 6: Prevalence (age and sex standardised) of physical health conditions (obesity, asthma, hypertension and diabetes) by deprivation quintile for SMI and all patients aged 15 to 74

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018

Figure 7: Prevalence (age and sex standardised) of physical health conditions (COPD, cancer, CHD and stroke) by deprivation quintile for SMI and all patients aged 15 to 74

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018 Note: change in y-axis scale to allow clear presentation Key: atrial fibrillation (AF), coronary heart disease (CHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure (HF)

While no clear trend across deprivation quintiles is evident for most physical health conditions in SMI patients, obesity and diabetes prevalence remains significantly higher for SMI patients compared to all patients across all quintiles (Figure 6). SMI patients experience approximately double the prevalence of obesity and diabetes, with potentially higher inequality in younger age groups (15-34). Asthma inequality increases with deprivation, although differences are not statistically significant in less deprived quintiles.

Rate ratios for some physical health conditions are higher in less deprived areas (Figures 6 and 7), suggesting deprivation partially explains health inequalities in SMI patients, but not entirely. These findings align with prior UK research documenting higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus, asthma, CHD, and COPD in SMI patients in the most deprived quintile, and higher prevalence of cancer and stroke in the least deprived quintile.

This analysis confirms a higher proportion of SMI patients reside in more deprived areas (Figure 2), with SMI prevalence increasing with socioeconomic deprivation. Even after standardizing for age and sex, health inequalities persist (Figure 3). To further understand demographic and socioeconomic factors, direct standardization adjusting for age, sex, and deprivation simultaneously was applied (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Prevalence (age, sex and deprivation standardised) of physical health conditions for severe mental illness (SMI) and all patients aged 15 to 74

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018 Key: coronary heart disease (CHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); AF and HF were not included in the analysis due to insufficient number of patients in each quintile to carry out robust analysis

After standardizing for age, sex, and deprivation, SMI patients still show higher prevalence (Figure 8) for:

- Obesity

- Asthma

- Diabetes

- COPD

- CHD

- Stroke

Prevalence of physical health conditions remains relatively unchanged after additional deprivation standardization (Figure 3), indicating deprivation only partially contributes to health inequalities between SMI and all patients. Standardized prevalence data shows SMI patients are nearly twice as likely to have diagnoses of obesity, diabetes, COPD, and stroke.

These findings suggest factors beyond demographics and deprivation contribute to poor physical health in SMI patients. The greater burden of physical health conditions in this population cannot be solely attributed to the higher prevalence of SMI among socially disadvantaged individuals, a major determinant of poor physical health.

The interplay between physical health, mental health, and social determinants is complex. The Kings Fund highlights the substantial contribution of co-morbidities and deprivation interactions to health inequalities. This is especially critical for SMI patients in deprived areas who experience multiple disadvantages and bear one of the highest burdens of poor physical health.

SMI and Multiple Physical Health Conditions

This analysis reveals that 41.4% of SMI patients have one or more of the 10 examined physical health conditions, compared to 29.5% of all patients. The proportion of SMI patients with one or more physical health conditions is higher across sexes, age groups, and deprivation quintiles (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Prevalence (age and sex standardised) of any physical health condition by sex, age and deprivation quintile for severe mental illness (SMI) and all patients aged 15 to 74

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018 Note: change in y-axis scale to allow clear presentation

Health inequality in the prevalence of one or more physical health conditions is greater in younger SMI patients. SMI patients aged 15-34 are 1.6 times more likely to have one or more physical health conditions, while the rate ratio is 1.1 for those aged 55-74.

Health inequality in physical health conditions between SMI and all patients approximately doubles for multi-morbidities (Figure 10). For example:

- Prevalence of 2 or more physical health conditions in SMI patients is 1.8 times higher than in all patients.

- Prevalence of 4 or more physical health conditions in SMI patients is 2 times higher than in all patients.

Figure 10: Prevalence of physical health multi-morbidities for severe mental illness (SMI) and patients aged 15 to 74

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018 Note: the percentages are not age and sex standardised.

Multi-morbidity patterns in the SMI population are consistent across sex, age, and deprivation. The percentage of SMI patients with 3 or more physical health conditions (Figure 11) is higher than all patients across sexes, age groups, and most deprivation quintiles.

Figure 11: Prevalence (age and sex standardised) of 3 and more physical health co-morbidities for severe mental illness (SMI) and all patients aged 15 to 74

Source: The Health Improvement Network (THIN), Active patients in England; data extracted May 2018

While multi-morbidity increases with deprivation in all patients, this trend is less evident in SMI patients. Rate ratios of 3 or more physical health conditions between SMI and all patients are higher across deprivation quintiles, but not statistically significant in two quintiles, and no clear gradient exists from least to most deprived.

Younger SMI patients with 3 or more physical health conditions exhibit the highest level of inequality, being 5 times more likely than all patients, compared to 1.4 times more likely in the 55-74 age group. Although the rate ratio is high in the 15-34 age group, overall prevalence remains low.

Individuals with multi-morbidities, including SMI, require holistic, patient-centered health, care, and support. Integrated care systems, bringing together NHS commissioners, providers, and local authorities, are crucial for improving health and care for these populations. Research suggests that integrated healthcare systems may facilitate earlier presentation for treatment with a range of medical co-morbidities in people with SMI.

SMI and Interventions to Improve Physical Health

Extensive research documents poor physical health in people with SMI, but underlying causes are not fully understood. Improving physical health requires addressing:

- Unhealthy behaviors: smoking, poor diet, lack of exercise, substance misuse.

- Multiple risk behaviors simultaneously.

- Antipsychotic medication side effects: weight gain, glucose intolerance, cardiovascular effects.

- Barriers to treatment access.

- Disconnected and irregular healthcare and support.

- Non-compliance with care processes.

- Impact of SMI on self-management.

- Socioeconomic determinants and consequences of mental illness: poverty, poor housing, social isolation, unemployment, stigma.

The NHS England Five Year Forward View emphasizes integrating mental and physical healthcare. Holistic, integrated services require changes across healthcare delivery. The Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) framework supports service quality improvements and new care models. Improving physical healthcare to reduce premature mortality in SMI remains a CQUIN goal, requiring services to:

- Demonstrate cardiometabolic assessment and treatment for psychosis.

- Demonstrate positive outcomes in BMI and smoking cessation in early intervention in psychosis (EIP) services.

- Collaborate with primary care clinicians.

Resources

The following resources aid providers and commissioners in improving physical healthcare for people with SMI:

- Improving physical healthcare for people living with SMI in primary care: NHS guidance on improving access to physical health checks and follow-up care, recommending annual full physical health assessments for adults on the SMI register.

- Practical toolkit for mental health trusts and commissioners: NHS toolkit for improving physical healthcare in hospital settings, using screening tools for cardiovascular risk and recommending interventions.

- Bipolar disorder assessment and management: NICE guideline covering bipolar disorder recognition, assessment, and treatment, including physical health monitoring.

- Coexisting SMI and substance misuse in community health and social care services: NICE guideline on improving services for individuals with coexisting SMI and substance misuse.

- Prevention and management of psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: NICE guideline on psychosis and schizophrenia management, emphasizing early recognition, treatment, and coexisting health problem checks.

- Mental health core skills education and training framework: Framework for improving workforce care for people with mental health issues, outlining core skills and knowledge.

- Improving the physical health of adults with SMI: Report with practical recommendations for ensuring equal physical healthcare standards for adults with SMI and reducing premature death risk.

- NHS RightCare ‘CVD prevention pathway for people with SMI’: (forthcoming publication).

Conclusions

This analysis confirms that patients with SMI in GP care experience poor physical health and significant health inequalities compared to all patients in THIN.

NICE guidelines recommend primary care use QOF registers to monitor SMI patient physical health and annual physical health reviews including weight/BMI, metabolic status, pulse, and blood pressure checks. While these checks may partially explain findings like higher obesity prevalence in SMI patients, the high level of health inequality and the breadth of physical health disorders involved suggest QOF register inclusion alone is insufficient.

Evidence suggests primary care incentives for physical health reviews in SMI patients improve identification but not treatment of cardiovascular risk factors. Research indicates lower quality physical health screening for SMI QOF register patients compared to those on physical health registers like diabetes.

This analysis supports existing guidance and recommendations for improving physical health management in people with SMI, including: [List of recommendations from the original article – these are implicitly contained within the ‘Interventions to Improve Physical Health’ and ‘Resources’ sections and do not need to be explicitly listed again in the conclusion to maintain conciseness and readability. If explicitly listing is desired, extract key recommendations and list them here.]

This analysis is limited to national-level findings. Sub-national health inequality data is needed to support local planning. Local GP data analysis is recommended to understand local co-morbidity prevalence and health inequalities in SMI populations, with PHE’s technical supplement providing methodological guidance.

Poor physical health in SMI extends beyond the conditions examined. Future research is needed to identify further health inequalities and understand causes, utilizing THIN and other primary care databases to analyze:

- Cancer-screening program access and uptake in SMI populations.

- Access to physical health checks and NHS Health Checks, including post-check interventions.

- Secondary care pathways for people with SMI.

- Risk stratification for targeted early intervention.

- Causes of physical health inequality in SMI, including demographic, socioeconomic, risk factors, biological markers, and antipsychotic medication use.

- Inequalities in preventable conditions and causes of premature mortality like liver disease, and mental health multi-morbidities like depression.

Authors and Acknowledgements

Authors

National Mental Health Intelligence Network, with contributions from Kate Lachowycz, Sulia Celebi, Gabriele Price, Cam Lugton, and Rachel Roche.

Acknowledgements

Simran Sandhu, Sue Foster, Russell Plunkett, Arvinder Duggal, Julia Verne, Sarah Holloway, Amy Clark, Rosie Frankenberg, Gyles Glover, Rita Ranmal, Anna Gavin, Katherine Henson, David Osborn, and Melissa Darwent. Co-funded by NHS England.