INTRODUCTION

Acute abdominal pain is a frequently encountered complaint in pediatrics, presenting a considerable diagnostic challenge due to the broad spectrum of potential underlying causes. While many instances of acute abdominal pain in children are benign and self-limiting, stemming from conditions like gastroenteritis, constipation, or viral infections, the critical task for healthcare professionals is to discern those children who are experiencing serious, potentially life-threatening conditions requiring prompt medical attention. These conditions include appendicitis, intussusception, volvulus, and adhesions. Although surgical intervention is needed in only about 1% of children presenting with acute abdominal pain, the risk of overlooking a severe organic etiology is a significant concern for clinicians. Adding to the complexity, some children with acute abdominal pain may not receive a definitive diagnosis during their initial evaluation because of the disease’s early stages or subtle, atypical signs. Accurate and timely diagnosis is paramount in preventing significant morbidity and mortality in these young patients. This article aims to provide a detailed overview of the pathogenesis, etiology, clinical evaluation, and management strategies for acute abdominal pain in children, offering a comprehensive guide for differential diagnosis.

UNDERSTANDING ABDOMINAL PAIN: PATHOGENESIS

Abdominal pain can be categorized into three main types based on the pain receptors involved: visceral, somatoparietal, and referred pain. Notably, visceral pain receptors are most commonly associated with abdominal pain.

Visceral pain receptors are distributed across the serosal surface, mesentery, intestinal muscle, and mucosa of hollow organs. These receptors are responsive to mechanical and chemical stimuli such as stretching, distension, contraction, and ischemia. Visceral pain is typically described as dull, cramping, and poorly localized, often felt in the midline due to the unmyelinated C-fibers that transmit these signals bilaterally to the spinal cord across multiple levels. Furthermore, visceral pain can be broadly mapped to three abdominal regions based on the embryological origin of the affected structures. Pain from foregut derivatives (e.g., stomach, duodenum, liver, pancreas) is generally perceived in the epigastric region. Midgut structures (e.g., small intestine, appendix, ascending colon, and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon) cause pain felt in the periumbilical area. Hindgut structures (e.g., distal third of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and upper anal canal) typically result in pain localized to the lower abdomen.

Somatoparietal pain originates from receptors located in the parietal peritoneum, muscles, and skin. Inflammation, stretching, or tearing of the parietal peritoneum activates myelinated A-δ fibers, which transmit sharp, intense, and well-localized pain to specific dorsal root ganglia. Patients experiencing somatoparietal pain often remain still as movement exacerbates the discomfort.

Referred pain, while well-localized, is felt in areas distant from the affected organ but within the same cutaneous dermatome. This phenomenon arises from the convergence of afferent neurons from different sites at the same spinal cord level. For instance, conditions irritating the diaphragm can manifest as pain in the shoulder or lower neck region.

ETIOLOGY: CAUSES OF ABDOMINAL PAIN IN CHILDREN

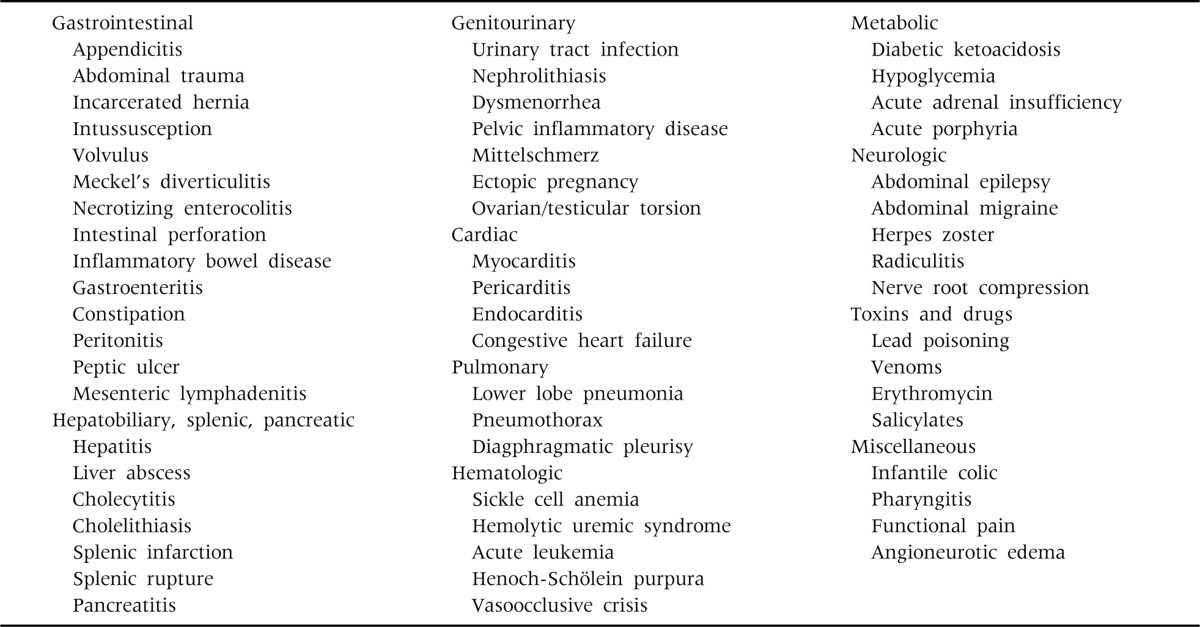

The etiology of acute abdominal pain in children is diverse, ranging from benign, self-limiting conditions to life-threatening surgical emergencies. A comprehensive list of potential causes is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Causes of Acute Abdominal Pain in Children

Alt text: Table 1 listing causes of acute abdominal pain in children categorized by surgical, medical, and extra-abdominal etiologies, including conditions like appendicitis, gastroenteritis, constipation, trauma, and infections.

Life-threatening causes of abdominal pain often involve hemorrhage, obstruction, or perforation of the gastrointestinal tract or intra-abdominal organs. These conditions are frequently associated with specific clinical signs that necessitate immediate recognition and intervention. Extra-abdominal causes, such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), and myocarditis, also present with distinct clinical features that aid in differential diagnosis. Common, less severe causes include gastroenteritis, constipation, systemic viral illnesses, extra-gastrointestinal infections (e.g., streptococcal pharyngitis, lower lobe pneumonia, and urinary tract infections), mesenteric lymphadenitis, and infantile colic.

Acute Appendicitis: The Most Common Surgical Emergency

Acute appendicitis stands as the most prevalent surgical cause of acute abdominal pain in children. The classic presentation of appendicitis begins with visceral pain – vague, poorly localized, periumbilical discomfort. Over 6 to 48 hours, as the inflammation extends to the overlying parietal peritoneum, the pain transitions to somatoparietal, becoming well-localized in the right lower quadrant. However, these typical manifestations are not always present, especially in younger children, making diagnosis more challenging. Therefore, appendicitis should be considered in any previously healthy child presenting with abdominal pain and vomiting, regardless of the presence of fever or focal abdominal tenderness. Early diagnosis is crucial to prevent complications such as perforation and peritonitis.

Abdominal Trauma: A Critical Consideration

Abdominal trauma, whether blunt or penetrating, can lead to a spectrum of injuries including hemorrhage or laceration of solid organs, bowel perforation, organ ischemia due to vascular injury, and intramural hematoma. Blunt abdominal trauma is more common in children, often resulting from motor vehicle accidents, falls, sports injuries, or child abuse. A thorough history and physical exam are essential in cases of suspected trauma to assess the extent and nature of injuries.

Intestinal Obstruction: Recognizing the Warning Signs

Intestinal obstruction typically manifests with characteristic cramping abdominal pain, often described as colicky. This type of pain should raise suspicion for serious intra-abdominal conditions requiring urgent diagnosis and surgical or non-surgical treatment. Causes of intestinal obstruction in children include intussusception, malrotation with midgut volvulus (especially in infants), necrotizing enterocolitis (in neonates), incarcerated inguinal hernia, and postoperative adhesions. Bilious vomiting is a hallmark sign of intestinal obstruction, particularly in infants.

Gastroenteritis: A Frequent Cause of Abdominal Discomfort

Gastroenteritis is the most common medical cause of abdominal pain in children. Viral agents, such as rotavirus, norovirus, adenovirus, and enterovirus, are the most frequent culprits, although bacterial and parasitic infections can also cause gastroenteritis. Children with acute gastroenteritis may experience fever, severe cramping abdominal pain, and diffuse abdominal tenderness, often preceding the onset of diarrhea. Dehydration is a significant concern in pediatric gastroenteritis, requiring careful monitoring and fluid management.

Constipation: A Common and Treatable Cause

Constipation is a frequent cause of abdominal pain, particularly in older children. Fecal impaction can lead to significant lower abdominal pain. Constipation is diagnosed based on criteria including infrequent bowel movements (less than three per week), fecal incontinence, palpable abdominal or rectal masses of stool, retentive posturing, and painful defecation. Dietary modifications and stool softeners are often effective in managing constipation-related abdominal pain.

Mesenteric Lymphadenitis: Mimicking Appendicitis

Mesenteric lymphadenitis, inflammation of the mesenteric lymph nodes, can present with abdominal pain that mimics appendicitis, as the mesenteric lymph nodes are predominantly located in the right lower quadrant. However, in mesenteric lymphadenitis, the pain is typically more diffuse, and signs of peritonitis are usually absent. Viral infections are the most common etiology, but bacterial gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and lymphoma are also potential causes. Ultrasound can be a helpful tool in differentiating mesenteric lymphadenitis from appendicitis.

Infantile Colic: Pain in Early Infancy

Infantile colic, especially in infants with hypertonic features, can cause significant abdominal pain. Colic is characterized by paroxysmal crying episodes where infants may draw their knees up to their abdomen, suggesting abdominal discomfort. Colic typically resolves with the passage of flatus or stool and usually improves after the first three to four months of life. While benign, colic can be distressing for both infants and parents.

CLINICAL EVALUATION: A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH

Evaluating a child with acute abdominal pain requires a meticulous approach, beginning with a detailed history and thorough, often repeated, physical examinations. Selective use of laboratory and radiological investigations is crucial to confirm a diagnosis and rule out serious pathology. However, despite a comprehensive initial evaluation, the diagnosis may remain uncertain, necessitating close observation and serial examinations in an emergency department setting to clarify any diagnostic ambiguities.

History Taking: Unraveling the Story of Pain

A detailed history is paramount in evaluating abdominal pain. Key aspects include the pain’s onset pattern, progression, location, intensity, character (e.g., sharp, cramping, dull), and any precipitating or relieving factors. Associated symptoms such as fever, vomiting, diarrhea, changes in bowel habits, urinary symptoms, and gynecological history in adolescent females are crucial. The patient’s age is a significant factor in differential diagnosis, as certain conditions are more prevalent in specific age groups (Table 2). Other important historical details include recent abdominal trauma, previous abdominal surgeries, and a comprehensive review of systems to identify extra-abdominal causes.

Table 2. Differential Diagnosis of Acute Abdominal Pain by Predominant Age

Note: Table 2 was referenced in the original article but not provided as an image. For the purpose of this exercise, I will proceed without including Table 2 image but acknowledge its importance in a real-world scenario.

Pain relief following a bowel movement may suggest a colonic origin, while pain improvement after vomiting might indicate a condition localized to the small bowel. In surgical conditions, abdominal pain typically precedes vomiting, whereas vomiting often precedes abdominal pain in medical conditions. Bilious vomiting in infants and children should always raise suspicion for bowel obstruction.

Physical Examination: A Hands-On Assessment

A careful physical examination is indispensable for accurate diagnosis. This should include examination of the external genitalia, testes, anus, and rectum as part of the abdominal pain evaluation. In sexually active adolescent females, a pelvic examination is also essential to rule out gynecological causes of abdominal pain.

General Appearance: Observing the Child’s Demeanor

The child’s general appearance can provide valuable clues. Children with peritoneal irritation often lie still and resist movement due to pain exacerbation, whereas those with visceral pain may change position frequently, writhing in discomfort to find a position of relief.

Vital Signs: Physiological Indicators

Vital signs assessment is crucial. Fever suggests an underlying infection or inflammation, such as acute gastroenteritis, pneumonia, pyelonephritis, or intra-abdominal abscess. Tachypnea may indicate pneumonia or metabolic acidosis. Tachycardia and hypotension are signs of hypovolemia or third-space fluid loss, requiring prompt fluid resuscitation.

Abdominal Examination: Palpation and Auscultation

The abdominal examination should be performed gently, starting away from the area of maximal tenderness and progressing towards it. The examiner must carefully assess the degree of abdominal tenderness, its location (localized vs. diffuse), rebound tenderness, rigidity, distension, presence of masses, and organomegaly. A rectal examination provides valuable information regarding sphincter tone, presence of rectal masses, stool consistency, and presence of hematochezia or melena.

Investigations: Guiding Diagnostic Accuracy

Specific laboratory studies and radiologic evaluations are valuable tools in assessing the patient’s physiological status and achieving an accurate diagnosis. A complete blood cell count (CBC) and urinalysis are generally indicated in all children presenting with acute abdominal pain. Serum glucose and electrolytes are essential to evaluate hydration status and acid-base balance, particularly in children with vomiting or diarrhea. A pregnancy test should be performed in postmenarcheal girls to rule out ectopic pregnancy or pregnancy-related complications. An algorithmic approach to managing children with acute abdominal pain requiring urgent intervention is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Algorithmic Approach to Acute Abdominal Pain in Children

Alt text: Figure 1 depicting an algorithmic approach for managing acute abdominal pain in children requiring urgent intervention, outlining steps from initial assessment to imaging and specialist consultation based on clinical findings.

Plain abdominal radiographs can be helpful when intestinal obstruction or perforation is suspected, revealing dilated bowel loops or free air. Chest radiographs can rule out pneumonia as a cause of referred abdominal pain. Ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT) are widely utilized imaging modalities in the emergency department to identify the etiology of abdominal pain. While CT offers higher accuracy, ultrasound is often preferred as the initial imaging modality for pediatric abdominal pain due to its non-invasive nature, lack of ionizing radiation, and lower cost. Ultrasound is particularly useful in evaluating for appendicitis, intussusception, and gynecological pathology.

MANAGEMENT: TARGETING THE UNDERLYING CAUSE

Management of acute abdominal pain in children should be directed at treating the underlying cause. As outlined in Figure 1, immediate intervention is necessary for children who appear prostrated or toxic, exhibit signs of bowel obstruction, or demonstrate evidence of peritoneal irritation. Initial resuscitation measures include addressing hypoxemia, correcting intravascular volume depletion with intravenous fluids, and managing metabolic derangements. Nasogastric tube decompression may be required in cases of bowel obstruction to relieve pressure and vomiting. Empiric intravenous antibiotics are often indicated when there is clinical suspicion of a serious intra-abdominal infection, such as appendicitis with perforation or peritonitis. Furthermore, adequate analgesia should be provided to children experiencing severe pain, ideally before surgical evaluation, to improve comfort and facilitate examination.

CONCLUSION

Acute abdominal pain is a common and challenging presentation in pediatric patients, frequently necessitating rapid diagnosis and treatment in emergency settings. While most cases are self-limiting and benign, the potential for serious, life-threatening conditions such as appendicitis, intussusception, or bowel obstruction necessitates a thorough and systematic approach to differential diagnosis. Meticulous history taking, repeated physical examinations, and judicious use of investigations are essential to determine the etiology of acute abdominal pain and to identify children requiring urgent surgical or medical intervention. Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for optimizing outcomes and minimizing morbidity and mortality in children presenting with abdominal pain.

References

Note: References from the original article should be listed here in a properly formatted manner. For the purpose of this exercise, I will omit listing them explicitly but acknowledge their importance in a complete article.