Diagnosing abdominal tuberculosis (TB) presents a formidable challenge, even for seasoned clinicians. Its ability to mimic various conditions and its atypical presentations often lead to diagnostic delays. A heightened sense of suspicion is paramount for timely diagnosis. Clinical and radiological indicators of abdominal TB are often nonspecific, necessitating a comprehensive diagnostic approach. This article shares insights gleaned over three decades, highlighting diagnostic pitfalls through illustrative case studies and presenting a refined diagnostic algorithm for abdominal TB. This algorithm aims to guide clinicians toward accurate diagnosis via histopathology or microbiology, categorizing clinical and radiological findings into five distinct presentations: (1) gastrointestinal, (2) solid organ lesions, (3) lymphadenopathy, (4) wet peritonitis, and (5) dry/fixed peritonitis. Endoscopy is crucial for diagnosing gastrointestinal TB and dry peritonitis. Ultrasound-guided aspiration is recommended for solid organ lesions, while wet peritonitis and lymphadenopathy may require ultrasound-guided aspiration followed by laparoscopy. Diagnostic laparotomy should be reserved as a last resort for histological confirmation. Capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy are not included in our primary algorithm due to limited evidence and accessibility, particularly in resource-constrained settings, and the potential risk of obstruction in small bowel strictures with capsule endoscopy. A definitive diagnosis is achievable in approximately 80% of cases, with therapeutic diagnosis considered for the remaining 20%.

Keywords: Abdominal Tuberculosis Diagnosis, Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis, Tuberculosis, Diagnosis, Algorithm, Surgery

Introduction

Charles Dickens poignantly described tuberculosis (TB) as “a dread disease in which struggle between soul and body is gradual quiet and solemn, that day by day, and grain by grain, the mortal part wastes and withers away.” This description remains relevant today. Tuberculosis continues to be a leading global health concern, ranking among the top 10 causes of death worldwide. In 2017, ten million individuals contracted tuberculosis, resulting in an estimated 1.3 million deaths [1]. Furthermore, latent tuberculosis infection affects approximately one-quarter of the world’s population [2]. The emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria further complicates the management of this disease.

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis accounts for roughly 20% of all tuberculosis cases [3], with abdominal tuberculosis comprising about 10% of extrapulmonary TB [4]. Tubercle bacilli can reach the abdomen through three primary routes: (1) ingestion of infected sputum or milk, (2) hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination, and (3) direct extension from the fallopian tubes into the peritoneum [4, 5]. Surgical intervention is necessary in approximately 15% of abdominal tuberculosis cases, with half performed emergently for complications such as obstruction, abscess, perforation, or hemorrhage, and the other half for diagnostic purposes [6]. Over the past 8 years, we have treated 24 confirmed cases of abdominal tuberculosis at Al-Ain Hospital in the United Arab Emirates, averaging three new cases annually in a hospital serving a population of 600,000. This translates to less than 1% of acute abdomen admissions and an abdominal tuberculosis incidence of approximately 0.5 per 100,000 population per year in our setting. In comparison, 44 cases were managed in Mubarak Al-Kabeer and Adan Hospitals in Kuwait between 1981 and 1990, serving a population of 1,250,000, indicating an incidence of 0.35 per 100,000 population per year. Among these 44 Kuwaiti patients, 18% also had pulmonary tuberculosis, and a smaller percentage presented with tuberculosis in other extrapulmonary sites (Abu-Zidan FM. Management of abdominal tuberculosis in the Gulf region. Unpublished data).

The diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis remains a significant clinical challenge. Increased global migration and rising HIV prevalence have led to a greater encounter with this condition in diverse clinical settings. We have observed persistent misconceptions about abdominal tuberculosis over the last three decades. These include the beliefs that (1) abdominal tuberculosis is rare, (2) it is invariably associated with active pulmonary tuberculosis, and (3) it is primarily a disease of impoverished populations [7]. These misconceptions can hinder even experienced clinicians from reaching a timely and accurate abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis.

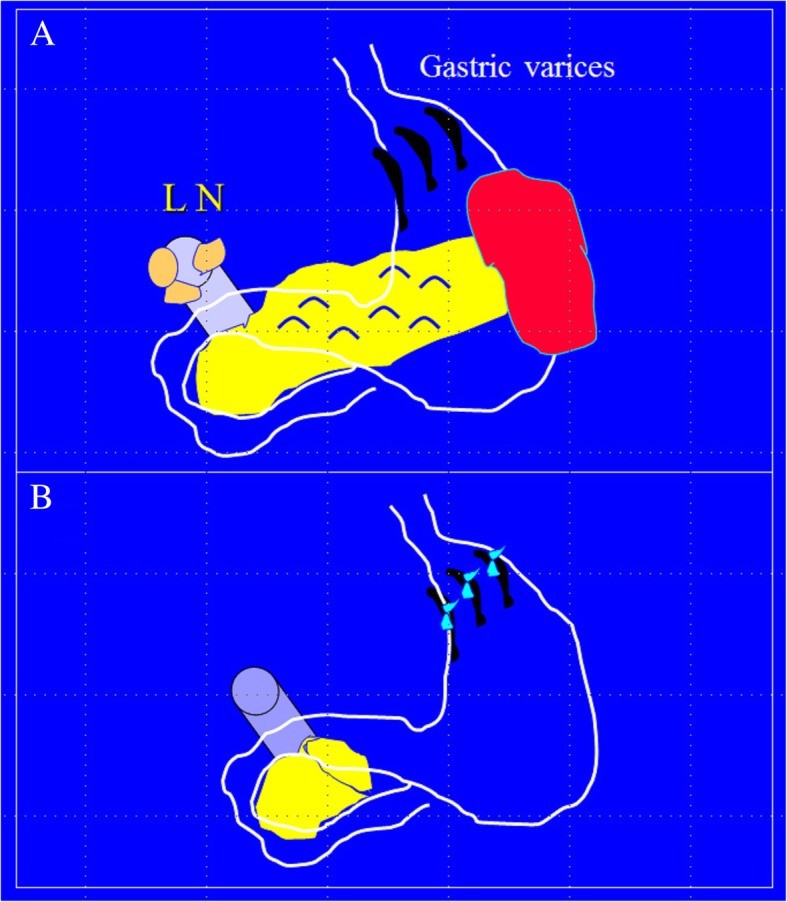

In 1990, the lead author (FAZ) reported a notable case of abdominal tuberculosis [8]. A 23-year-old male presented with severe hematemesis due to gastric varices caused by lymph node compression of the portal vein (Fig. 1a). Laparotomy revealed a matted mass in the pancreatic region, mimicking a pancreatic tumor. Intraoperative frozen section analysis was inconclusive. The patient underwent extensive surgery, including distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, removal of porta hepatis lymph nodes, and variceal ligation (Fig. 1b). Histopathology unexpectedly confirmed abdominal tuberculosis in the lymph nodes. The patient received anti-tuberculosis treatment and follow-up CT scans and endoscopy at 18 months were normal. This case underscores that medical management alone might have sufficed had the diagnosis been established preoperatively. Abdominal tuberculosis is fundamentally a medical condition, and surgical interventions should be reserved for complications like obstruction, perforation, fistulation, or hemorrhage [4, 5, 9].

Fig. 1.

A 23-year-old male presented with severe hematemesis due to gastric varices. Laparotomy revealed a pancreatic region mass and portal vein-compressing lymph nodes, resembling pancreatic cancer (a). The patient underwent major surgery including distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, porta hepatis lymph node removal, and variceal ligation (b). Histopathology confirmed abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis. (Illustration by Professor Fikri Abu-Zidan, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, UAE University). Full clinical details previously published [8]

This striking presentation sparked a deep interest in the complexities of abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis. This article aims to share critical lessons learned over three decades. With increasing global migration, these insights are particularly relevant for clinicians, especially in developed nations, who may have limited prior experience with abdominal tuberculosis. We will illustrate each lesson with a relevant clinical case and present a diagnostic algorithm developed over years of experience, applicable globally, including in low- and middle-income countries, to improve abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis.

Lesson 1: Abdominal Tuberculosis: The Great Mimicker

The initial case (Fig. 1) highlights a crucial lesson: abdominal tuberculosis is a master of disguise [5, 9]. Its ability to affect isolated abdominal organs without lung involvement and mimic other conditions necessitates a high degree of clinical suspicion [5, 9, 10]. Our experience includes cases where isolated abdominal organ tuberculosis mimicked pancreatic tumors, colon cancer, gastric cancer, and lymphomas. It can also simulate infectious conditions like appendicitis, acute cholecystitis, typhoid fever, and necrotizing fasciitis [11–14]. Even in regions with high TB prevalence, accurate clinical diagnosis is achieved in only about half of patients [15]. In our series, malignancy was the preoperative diagnosis in 25% of cases [16].

Lesson 2: Non-Specific Radiological Findings in Abdominal TB Diagnosis

Ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) scans are valuable imaging modalities, but radiological findings in abdominal TB are often nonspecific. They may reveal generalized or localized ascites with thin mobile septations, thickened omentum and peritoneum, lymphadenopathy, or bowel wall thickening [4, 17–19]. CT scan is the preferred modality for assessing the extent and characteristics of abdominal tuberculosis [4, 5, 10, 20, 21]. However, these radiological findings are not pathognomonic [22], and microbiological or histopathological confirmation through percutaneous aspiration or direct biopsy is essential [18] for a definitive abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis.

Lesson 3: Liver Tuberculosis and CT Scans: What You Might Miss in Abdominal TB Diagnosis

A normal abdominal CT scan does not exclude hepatic tuberculosis. Miliary hepatic TB, characterized by small granulomas, can be easily missed by CT imaging [20, 22, 23] and may only be detectable through biopsy (Fig. 2). In cases of high suspicion for hepatic tuberculosis, particularly with elevated bilirubin levels in unexplained severe sepsis unresponsive to broad-spectrum antibiotics in TB-endemic regions, a liver biopsy is advisable, even if ultrasound and CT scans of the liver appear normal. This is critical for accurate abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis and management.

Fig. 2.

A 39-year-old African man, 3 months post-renal transplant, presented with unexplained high fever and rapid organ function deterioration, progressing to ICU admission for severe sepsis. Despite empirical antibiotics, his condition worsened, with renal function decline and elevated bilirubin and liver enzymes. Tuberculosis was suspected due to prior TB exposure history, despite normal liver CT findings (increased enhancement without focal lesions). Liver biopsy confirmed TB. a Hematoxylin and Eosin (× 4) showing a well-defined granuloma (arrows) in liver tissue without caseous necrosis or giant cells. b Ziehl-Neelsen stain (× 40) revealing numerous red rods or bacilli (black arrows) of mycobacterium tuberculosis. Epithelioid macrophages (red arrow) and lymphocytes are also visible (Courtesy of Navidul Haq Khan, Consultant Pathologist, Tawam Hospital, Al-Ain, UAE).

Lesson 4: A Diagnostic Algorithm for Abdominal Tuberculosis

Clinical and radiological findings in abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis are not definitive. Culture results can take up to six weeks, emphasizing the need for early histopathological diagnosis to initiate prompt treatment [9]. Our diagnostic approach categorizes clinical and radiological presentations of abdominal tuberculosis into five categories: (1) gastrointestinal, (2) solid organ lesions, (3) lymphadenopathy, (4) wet peritonitis, and (5) dry/fixed peritonitis [4, 5] (Fig. 3). Endoscopy with biopsy is effective for diagnosing gastrointestinal tuberculosis and dry peritonitis. Diagnostic accuracy improves with multiple biopsies [4, 10, 24]. Colonoscopy biopsies in 50 patients with colonic tuberculosis yielded a diagnostic rate of 80% [24]. Ultrasound-guided aspiration is valuable for diagnosing solid organ lesions [25–27]. For wet peritonitis and lymphadenopathy, ultrasound-guided aspiration is the initial step, followed by laparoscopy if necessary [28–30]. Diagnostic laparotomy should be reserved as the final option for obtaining histological confirmation in abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis.

Fig. 3.

The diagnostic algorithm for abdominal tuberculosis categorizes clinical and radiological findings into five types: (1) gastrointestinal, (2) solid organ lesions, (3) lymphadenopathy, (4) wet peritonitis, or (5) dry/plastic peritonitis.

Capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy are not routinely included in our diagnostic algorithm for abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis due to limited data on their utility in this context [4]. These modalities are not commonly utilized for abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis in our setting, are expensive, require specialized expertise, and are less accessible in low- and middle-income countries. Furthermore, capsule endoscopy carries a risk of complete intestinal obstruction in patients with small bowel strictures.

Lesson 5: Proceed with Caution: Laparoscopy in Fibrotic-Fixed Peritonitis for Abdominal TB Diagnosis

Tuberculous peritonitis presents in three main forms: (1) wet type (most common, ~90% of cases) with free or localized ascites, (2) dry type (plastic) with peritoneal nodules and adhesions, and (3) fibrotic-fixed type characterized by matted bowel loops and thickened mesentery and omentum [4, 19, 31]. Laparoscopy is increasingly used for diagnosing tuberculous peritonitis [9]. However, we advise against laparoscopy in the fibrotic-fixed type due to the high risk of iatrogenic bowel injury and fistula formation, as space for laparoscope insertion may be limited. Laparotomy may be more appropriate in these cases if biopsy is required (Fig. 4). This is particularly relevant in tuberculous abdominal cocoon, often diagnosed intraoperatively, which necessitates open surgery to release the fibrous encasement of the bowel [32]. Ultimately, the decision for laparoscopy depends on the surgeon’s laparoscopic expertise and familiarity with abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis and its varied presentations.

Fig. 4.

A 50-year-old male with a year-long history of abdominal pain and weight loss presented with a left lower quadrant abdominal mass, anemia (hemoglobin 87 g/L), and hypoalbuminemia (28 g/L). Abdominal ultrasound (a) showed matted bowel loops, thickened mesentery, and intraperitoneal fluid. CT abdomen revealed thickened intestine with localized ascites and small retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Diagnostic laparoscopy for biopsy (b) was challenging and resulted in suspected small bowel perforation. Laparotomy revealed matted small bowel, and intraoperative frozen section confirmed abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis. Two iatrogenic small bowel perforations were repaired. The patient developed a postoperative small bowel fistula (yellow arrow).

Lesson 6: The Value of Therapeutic Diagnosis in Abdominal Tuberculosis

Therapeutic diagnosis rates in various studies range from 16% to 29% [16, 24, 33, 34]. Figure 5 illustrates a successful therapeutic diagnosis. In this case, despite inconclusive laboratory and nonspecific radiological findings, abdominal tuberculosis was suspected, and therapeutic diagnosis proved effective. Definitive diagnosis is achievable in only about 80% of patients; therapeutic diagnosis should be considered in the remaining 20%. Most patients will show rapid improvement with anti-TB treatment, typically within two weeks [4], supporting the abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis.

Fig. 5.

A 44-year-old woman presented with 3-day abdominal pain, distended, tender but soft abdomen, fever, leukocytosis, and elevated C-reactive protein. Abdominal CT (a) showed multiple intra-abdominal fluid collections (yellow arrow). Ultrasound-guided aspiration yielded green pus with negative culture and undetermined quantiferon-TB test. Suspecting abdominal tuberculosis, therapeutic diagnosis was initiated, resulting in dramatic abscess size reduction after 2 months (b). (Courtesy of Dr. Hussam Mousa, Consultant General Surgeon, Al-Ain Hospital, Al-Ain, UAE).

Lesson 7: Differentiating Abdominal TB from Crohn’s Disease: A Crucial Diagnostic Challenge

Initiating steroid treatment for presumed Crohn’s disease in patients with undiagnosed abdominal tuberculosis can have severe and even fatal consequences [4, 9]. Distinguishing between these conditions is challenging, necessitating every effort to obtain microbiological or histopathological evidence for accurate abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis. Local disease prevalence should be considered, and caution exercised before starting steroids. When diagnostic uncertainty exists, a therapeutic trial of anti-tuberculosis treatment may be a safer diagnostic approach before considering steroids.

Advancements in Laboratory Investigations for Abdominal TB Diagnosis

Recent years have seen advancements in immunological and molecular diagnostic techniques for tuberculosis. However, a simple, globally accessible, and cost-effective laboratory test for routine extrapulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis remains an unmet need. Cost is a significant limitation for many newer techniques [35]. Interpretation of published data requires caution, as high sensitivity and specificity may not translate to equally high positive and negative predictive values in clinical practice, which are influenced by disease prevalence. Furthermore, these advanced tests do not replace traditional AFB smear and culture [36]. The WHO recommends against using interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) or tuberculin skin tests (TST) for active TB diagnosis in low- and middle-income countries [37], noting that IGRAs are more expensive and complex than TST, with comparable results.

When routine laboratory and microbiology tests are inconclusive, molecular biology-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may support clinical suspicion while awaiting culture and drug susceptibility results [36]. However, PCR cannot differentiate between live and dead M. tuberculosis [36, 38], potentially remaining positive long after treatment completion and bacterial death. PCR is best suited for initial diagnosis, not for follow-up [36]. Moreover, research lab performance may not be replicated in clinical service labs due to contamination, technical errors, and sampling issues, potentially leading to false positives and reduced test generalizability [36].

Currently, the WHO recommends the Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for TB diagnosis, providing results within 2 hours [39]. Meta-analysis indicates high specificity but limited sensitivity for extrapulmonary TB detection with Xpert. A positive Xpert result can rapidly confirm TB, but negative results do not rule out the disease [40] in abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis.

Conclusions

Tuberculosis remains a global health crisis. Acute care surgeons must be aware of the diagnostic complexities of abdominal tuberculosis and strive to avoid surgery unless absolutely necessary [41]. In emergency settings, surgeons may face situations of peritonitis, unresolved bowel obstruction, or suspected bowel ischemia with systemic sepsis, where nonspecific CT findings add to the diagnostic dilemma. Experienced surgeons might opt for emergency laparoscopy or laparotomy and unexpectedly discover abdominal tuberculosis. A simple, cost-effective, routine diagnostic laboratory test for abdominal tuberculosis is still lacking. Currently, abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis relies on integrating clinical, laboratory, radiographic, and pathological findings. A high index of suspicion remains crucial. We have shared our diagnostic challenges and presented our diagnostic algorithm for abdominal tuberculosis, developed over years of experience, hoping it will prove valuable for acute care surgeons in improving abdominal tuberculosis diagnosis and patient care.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Data sharing statement

There is no additional data to share.

Abbreviations

CT: Computer tomography

IGRA: Interferon-gamma release assay

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction

TB: Tuberculosis

TST: Tuberculin skin test

WHO: World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

AFM conceived the idea, critically reviewed the literature, provided images, authored the manuscript, and approved the final version. MS-H contributed to the concept, critically reviewed the literature on laboratory TB diagnosis, assisted in manuscript preparation, and approved the final version. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This paper contains no patient-identifiable information. Only radiological and histopathological images are used. Patients were treated in two different countries over 30 years, making it impossible to obtain informed consent retrospectively.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral regarding jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fikri M. Abu-Zidan, Phone: +971-3-7137579, Email: [email protected]

Mohamud Sheek-Hussein, Email: [email protected].

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

References

-

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

-

Houben RMGJ, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016;20(3):217–25.

-

Sharma SK, Mohan A, Kohli MK. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2010;4(4):521–55.

-

Debi U, Ravisankar V, Kakkar N, Behra R, Sharma R, Singh K. Abdominal tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract: revisited. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(40):14831–40.

-

Chow KM, Chow VC, Hung LC, Wong SM, Chang TM, Chau TN, et al. Tuberculous peritonitis–associated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: a 10-year experience and review of literature. Kidney Int. 2002;61(4):1624–32.

-

Seror D, Israel-Biet D, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Valleur P, Bernades P. Abdominal tuberculosis: analysis of 25 cases. Gut. 1993;34(4):533–7.

-

Ersoy Y, Caner SS, Demirbas S, Karabulut N, Bayraktaroglu S, Sayiner ZA, et al. Abdominal tuberculosis: experience of 108 cases in Turkey. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(47):7876–9.

-

Abu-Zidan FM, Sheek-Hussein MM, Ali MM, Sakr M. Gastric varices due to tuberculous lymphadenopathy: an unusual cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11(1):91–4.

-

Bhansali SK. Abdominal tuberculosis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32(3):159–71.

-

Kapoor VK. Abdominal tuberculosis. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74(878):459–67.

-

Al-Sulaiman FA, Abu-Zidan FM. Tuberculous necrotizing fasciitis: a case report. J Trauma. 1995;39(3):598–600.

-

Elsayes KM, Oldham SA, Narra VR, Lewis JS Jr, Pillai RB. Abdominal and pelvic tuberculous masses: imaging findings and clinical features. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29(6):729–41.

-

Sharma R, Padda MS, Rana SS, Bhasin DK, Singh K. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis: a diagnostic dilemma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(25):3141–3.

-

Agarwal V, Chandra R, Aggarwal R, Singh S, Verma GR, Saraswat VA. Abdominal tuberculosis masquerading as carcinoma of stomach and colon. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2003;22(5):188–9.

-

Farer LS, Hopewell PC, Leong JL, Reichman LB, Riley RL, Jasmer RM, et al. Treatment of tuberculosis. American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-11):1–77.

-

Alrajhi AA, Rostom AY, Ibrahim EA. Abdominal tuberculosis: experience over 20 years in a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(13):1948–52.

-

Epstein BM, Mann JH. CT of abdominal tuberculosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;139(5):861–6.

-

Singh P, Chandra R, Kapoor VK, Singh R, Kumar L, Sharma AK. Diagnostic accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology in abdominal tuberculosis. J Cytol. 2014;31(4):207–10.

-

Pereira JM, Madureira AJ, Vieira A, Ramos I, Lazaro A, Morais H, et al. Abdominal tuberculosis: imaging features. Eur J Radiol. 2005;55(2):173–80.

-

Burrill J, Miller R, Banerjee R, Ramsay J, Utley M, Khalique L. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2018;32(1):21–38.

-

Manohar A, Simjee AE, Haffejee AA, Pettengell KE. Symptoms and investigative findings in 145 patients with tuberculous peritonitis diagnosed by peritoneoscopy and biopsy over a five year period. Gut. 1990;31(10):1130–2.

-

Mert A, Ozaras R, Tabak F, Bilir M, Senturk H, Ozturk R. Abdominal tuberculosis: diagnostic difficulties and frequency of complications in 38 cases. Intern Med J. 2003;33(11):473–9.

-

Alvarez SZ, Shell CG, Berk SL. Hepatic tuberculosis. J Hepatol. 1990;10(3):379–84.

-

Bhargava DK, Tandon R, Shriniwas, Singh R, Sachdev GK, Kapur BM, et al. Diagnosis of ileocecal and colonic tuberculosis by colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38(6):677–9.

-

Agarwal AK, Singh S, Singh SE. Role of imaging-guided percutaneous aspiration and drainage in abdominal tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc. 2011;58(1):24–30.

-

Patel N, Amarapurkar D, Agrawal S, Patel S, Shah D, Rathi P, et al. Solid organ tuberculosis: experience over a decade in a tertiary referral center. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2015;34(6):389–96.

-

Sanai FM, Bzeizi KI. Systematic review: tuberculous peritonitis–presenting features, diagnostic strategies and treatment outcome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(8):685–700.

-

Drewe J, Fruehling A, Dwyer R. Diagnostic laparoscopy for tuberculous peritonitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43(6):662–3.

-

Sharma MP, Bhatnagar S, Verma N, Kumar A, Mathur M. Diagnostic accuracy of peritoneoscopy and laparoscopic guided biopsies in abdominal tuberculosis. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2001;43(2):89–95.

-

Sriram PV, Misra SP, Kasthuri AS, Gupta SK. Diagnostic laparoscopy in疑腹腔结核病例的诊断性腹腔镜检查. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11(4):323–5.

-

Yamada T, Alpers DH, Kalloo AN, Kaplowitz N, Owyang C, Powell DW. Textbook of gastroenterology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

-

Foo FJ, Chia YW, Tan JY. Tuberculous abdominal cocoon: a rare cause of subacute small bowel obstruction. Singapore Med J. 2011;52(12):e235–7.

-

Shaw JA, Rimmer MJ, Westaby D, O’Donohue J, Portmann B, Williams R. Diagnostic laparoscopy for suspected abdominal tuberculosis. Gut. 1992;33(9):1274–6.

-

Simsek H, Yildiz M, Balci NC, Baran B, Tugsel R, Hamaloglu E. Diagnostic laparoscopy in abdominal tuberculosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47(36):1683–6.

-

Pai M, Behr MA, Dowdy D, Dheda K, Divangahi M, Boehme CC, et al. Tuberculosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16076.

-

Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Kunst H, Gibson A, Cummins E, Waugh N, et al. A systematic review of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of tuberculosis infection. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(3):iii–iv 1–196.

-

World Health Organization. Policy statement on interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

-

Moore DA. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis in resource-poor countries. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):910–1.

-

Boehme CC, Nabokov A, Michael JS, Gurtman A, Pershing DH, Cox C, et al. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis, rifampicin resistance, and isoniazid resistance by multiplex real-time PCR assay. Lancet. 2010;375(9732):2171–7.

-

Denkinger CM, Schumacher SG, Boehme CC, Dendukuri N, Pai M, Ramsay A, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):435–46.

-

Yazici P, Weyker PD, Katz P. Abdominal tuberculosis: challenging the surgical dogma. Am Surg. 2006;72(1):73–5.