Introduction

Abdominal Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome, commonly known as ACNES, might sound like a rare and complex condition. However, for clinicians specializing in pain management and diagnosis, particularly in cases of unexplained abdominal discomfort, Acnes Diagnosis should be a primary consideration. It is a condition frequently encountered, and recognizing it is crucial for effective patient care. When patients present with abdominal pain without clear indications of other significant underlying issues, ACNES needs to be promptly and thoroughly investigated as a highly probable diagnosis.

The medical community has recognized and documented ACNES and similar conditions for centuries. Starting as early as 1792 with J P Frank’s description of “peritonitis muscularis,”1 numerous studies and articles have highlighted the importance of understanding and correctly diagnosing this syndrome.2–9 These publications consistently point out a critical issue: abdominal wall pain is often misattributed to problems within the abdomen itself. This diagnostic error leads to unnecessary medical consultations, extensive and costly testing, and, in some cases, even avoidable abdominal surgeries. All of these can be prevented through accurate acnes diagnosis by the initial healthcare provider.

Research has quantified the significant financial burden associated with misdiagnosed ACNES. A 1999 study involving 117 patients led by Greenbaum10 estimated the wasteful expenditure on needless investigations to be around $914 per patient. Further studies in 2001 by Thompson et al11 revealed an even more alarming average cost of $6727 per patient for prior diagnostic tests and hospital fees before correct acnes diagnosis. Hershfield6 documented a range of initial misdiagnoses in patients eventually found to have ACNES. These included irritable bowel syndrome, spastic colon, gastritis, psychoneurosis, depression, anxiety, hysteria, and even malingering. It’s notable that many patients were incorrectly labeled with psychiatric conditions simply because their true ailment remained undiagnosed. The reality is, nerve entrapment at the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle is the most frequent source of abdominal wall pain.3,5,8,9,12 Carnett,3 in the early 20th century, termed this condition “intercostal neuralgia” and reported seeing an average of three patients with this condition weekly, and even up to three per day in consultation settings. In a primary care setting, it’s not uncommon to encounter one or two patients with ACNES for every 150 patients seen overall. In busier clinics, particularly during evening hours with multiple clinicians, the incidence can be as high as three ACNES patients per consultation session.

The presentation of ACNES can vary with timing. Acute episodes are often observed in the evening, particularly during the more active seasons of spring and summer. Conversely, chronic and recurring cases are more likely to present during daytime hours throughout the year.

To mitigate patient distress, prevent unnecessary time off work, and avoid the costs and potential risks associated with excessive diagnostic procedures, it is paramount that the first healthcare provider to evaluate the patient is proficient in acnes diagnosis. Drawing from both personal clinical experience and the extensive research of others in the field of ACNES, this article aims to equip readers with the essential knowledge and techniques for accurate acnes diagnosis and effective management of this often-overlooked condition.

Pathophysiology of ACNES

Understanding the pathophysiology is crucial for accurate acnes diagnosis. Kopell and Thompson13 elucidated that peripheral nerve entrapment commonly occurs at specific anatomical locations. These are areas where nerves change direction, entering fibrous or osseofibrous tunnels, or where nerves traverse fibrous or muscular bands. Entrapment at these points is likely due to the increased susceptibility of these locations to mechanically induced irritation. Muscle contractions in these areas can further exacerbate the issue through direct compression, and potentially also through traction on the nerve due to muscle activity. Mechanical irritation leads to localized swelling, which can directly injure the nerve or compromise its blood supply. Tenderness in the main nerve trunk may be found either proximal or distal to the point of entrapment, known as the Valleix phenomenon. Proximal tenderness can arise from vascular spasms or unnatural traction on the nerve trunk against the entrapment site. In ACNES, all of these mechanisms can be actively involved.

Anatomy Pertinent to ACNES

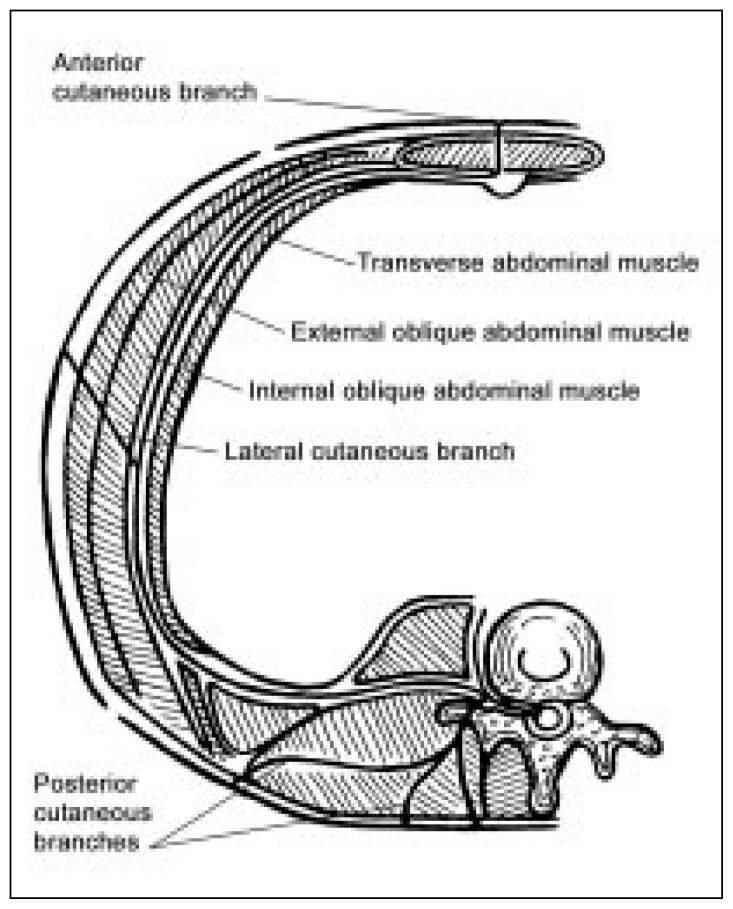

A detailed understanding of the relevant anatomy is essential for effective acnes diagnosis and treatment. The thoracoabdominal nerves, which terminate as cutaneous nerves, are anchored at six key points (Figure 1):14

- The spinal cord, their origin point.

- The location where the posterior branch originates.

- The point of origin of the lateral branch.

- The site where the anterior branch makes a near 90° turn to enter the rectus channel.

- The point within the rectus channel where accessory branches are given off, as seen in detailed microphotographs.15

- The skin, their terminal point.

Figure 1.

The most frequent cause of abdominal wall pain, crucial for acnes diagnosis, is nerve entrapment at the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle. Within the rectus channel, the nerve and its accompanying vessels are encased in fat and connective tissue. This arrangement binds the nerve, artery, and vein into a distinct bundle that can function as an independent unit from the surrounding tissue. Approximately three-quarters of the way through the rectus muscle (from back to front), a fibrous ring provides a smooth passage through which this bundle can slide. Anterior to this ring, the rectus aponeurosis offers a hiatus for the bundle to exit.

The hypothesis regarding nerve ischemia suggests it is caused by localized compression of the nerve at the fibrous ring level. This is due to the close proximity of the soft neurovascular bundle to the rigid ring. Herniation of the bundle through the ring, whether from excessive pressure from behind or traction from in front, can compress both the vessels and the nerve itself. Excessive traction on the bundle, from either direction, can cause it to be repeatedly rubbed against the ring, leading to irritation and swelling even before actual herniation occurs.

Any factor that increases pressure behind the abdominal wall can lead to the bundle herniating through the fibrous ring and aponeurotic opening. Abdominal muscle use can further aggravate this. Abdominal enlargement from any cause will increase traction on the nerves. Scars or sutures near the nerve anterior to the rectus muscle16–18 can directly compress the nerve or increase traction. Differential movement between skin and muscle can worsen this situation. Although any major nerve branch can become symptomatic, anterior branches are most commonly affected because nerve stretching is greatest at the point furthest from the origin (the spinal cord). The anterior branches enter the back of the muscle at nearly a right angle, making them more vulnerable to mechanical irritation compared to the posterior and lateral branches, which enter at a more oblique angle. Lateral branches are affected by lateral bending and trunk twisting, while posterior branches are impacted by bending, lifting, and twisting motions. Accessory branches perforate the muscle wall both above and below the main branches and also exit from adjacent muscle masses. These branches are often difficult to palpate unless they become symptomatic and tender.

Diagnosing ACNES

Clinical Presentation

Recognizing the clinical presentation is a key step in acnes diagnosis. Symptoms of ACNES can manifest as either acute or chronic pain. Acute pain is typically localized and described as dull or burning, often with a sharp component. It is usually unilateral, radiating horizontally in the upper abdomen and obliquely downwards in the lower abdomen. This pain can be exacerbated by twisting, bending, or sitting up, while lying down may provide some relief, although in some instances it can worsen the pain. Younger, more physically active individuals are more frequently seen for the initial episode of acute pain. The pain might begin during the night but often doesn’t prevent them from working the following morning. However, persistence and worsening of the pain, along with fear of being unable to work the next day, often prompt them to seek medical attention in the evening. Young women frequently express concern about their “ovaries,” “kidneys” (often meaning the bladder), or both.

It’s important in acnes diagnosis to address the ovarian complaint specifically, as it is a common initial concern for women presenting with ACNES.16,17,19,20 Young people, particularly those newly sexually mature, are often very aware of their gonads. Men have the advantage of easily examining their testicles due to their external location. Women’s ovaries, however, being internal, are not accessible for self-examination, except by medical professionals. Consequently, women may attribute any abdominal discomfort to an ovarian issue until proven otherwise. When a patient reports “pain in the ovary,” while it is essential to examine the ovaries, it’s also crucial to remember that this can be a common presentation of ACNES.

Misattribution of abdominal pain to gynecological issues is not exclusive to women. Slocomb20 noted that in 30% to 76% of diagnostic laparoscopic procedures performed for pelvic pain, the tissues were found to be normal. This raises concerns about surgical explorations and removal of normal pelvic structures in women with chronic pelvic pain, when the actual source of the pain is in the abdominal wall, highlighting the importance of accurate acnes diagnosis. One case involved a woman who underwent surgery for an “ovarian cyst” and later for “adhesions,” yet continued to experience the same pain, which was ultimately diagnosed as ACNES.5 A study of 120 emergency hospital admissions for abdominal pain21 found that 23 out of 24 patients with a positive Carnett’s sign (discussed below) who underwent abdominal surgery had no intra-abdominal pathology; their pain originated from the abdominal wall, emphasizing the need for improved acnes diagnosis.

Young men with ACNES often present during the daytime with complaints of “hernia” or “ulcer,” conditions commonly associated with men. Older individuals, both men and women, may express concerns about cancer, which is understandable given the age demographic. These patients might require further investigation, even if ACNES is the primary cause of their pain. A history of multiple abdominal surgeries should raise suspicion for ACNES. The presence of several surgical scars on the abdomen should alert the examiner to consider this possibility in acnes diagnosis.

Chronic ACNES complaints are typically seen during daytime in older patients. Their medical history often reveals acute pain exacerbations lasting days or weeks, followed by pain-free periods that can extend for years. One patient reported intermittent pain for 47 years.5 He had long since accepted the pain as inconsequential but was relieved to understand its cause through acnes diagnosis. If a patient states, “I have this pain in my stomach, and nobody seems to find the cause,” ACNES should be immediately considered.

ACNES-related pain is usually well-localized and predominantly unilateral. However, it can occur bilaterally at the same level, especially in the lower abdomen, or involve multiple nerves on opposite sides at different levels. Pain radiating into the scrotum or vulva suggests involvement at the T12/L1 level, but conditions like inguinal or femoral hernia and pain from the adductor muscles of the thigh must be excluded during acnes diagnosis. Pain and tenderness posterolaterally just below the iliac crest can also indicate T12/L1 involvement. This is a valuable diagnostic sign because it is present in abdominal wall pain but absent in pain originating from within the abdomen.3 Pain from T11 and T12 involvement radiates obliquely, following the nerve pathways. Such pain can mimic urolithiasis; however, patients with urolithiasis are typically in severe, restless pain, whereas ACNES patients tend to lie still with a hand over the painful area. Right-sided T11 involvement may suggest appendicitis, while involvement on either side might suggest ovarian issues or spigelian hernia. All of these conditions should be differentiated through thorough physical examination in acnes diagnosis. Pain on the right side at the T8 or T9 level could suggest cholecystitis or peptic ulcer; however, as Carnett3 noted, deep tenderness without peritoneal involvement is not characteristic of these conditions. Pain at T6, T7, or T8 levels may indicate pleurisy, costochondritis, or slipping rib syndrome (possibly a form of ACNES due to traction). Pain and numbness in the lateral thigh and hip might be meralgia paresthetica, also caused by nerve entrapment, specifically of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve at the iliac ligament and anterosuperior iliac spine.13 For a comprehensive list of conditions other than ACNES that can cause abdominal wall pain, refer to Carnett,3 Hershfield,6 Suleiman and Johnston,9 Gallegos and Robsley,17 and Greenbaum.22 These resources are invaluable for differential acnes diagnosis.

Patients with chronic ACNES often experience significant anxiety and fear of having an undiagnosed serious condition. Consequently, they may receive psychiatric diagnoses like anxiety, somatization, or depression, and are frequently prescribed antidepressants, tranquilizers, muscle relaxants, or pain relievers. Such a medical history should prompt consideration of ACNES in the differential acnes diagnosis.

Physical Examination

A detailed physical examination is paramount for accurate acnes diagnosis. A suggestive medical history should guide the examiner to precisely locate the tender spot by asking the patient, “Where exactly is the pain?” Patients usually indicate a general area with several fingers. The examiner should then ask, “Show me with one finger.” As the patient pinpoints the exact spot with a fingertip, often pressing harder to locate it precisely, they typically exclaim “Right here!” and flinch when the tender point is pressed.

To proceed effectively with the examination and acnes diagnosis, the examiner must be familiar with the precise anatomical locations of each neuromuscular foramen. Practicing palpating these depressions on one’s own abdomen and on others is essential. Furthermore, during routine abdominal examinations, the examiner should routinely palpate for these aponeurotic openings. Their size can vary significantly between individuals. Larger openings, often found in obese patients, are easier to palpate, aiding in familiarizing the examiner with the feel of a foramen, which is beneficial when encountering smaller dimensions in other patients.

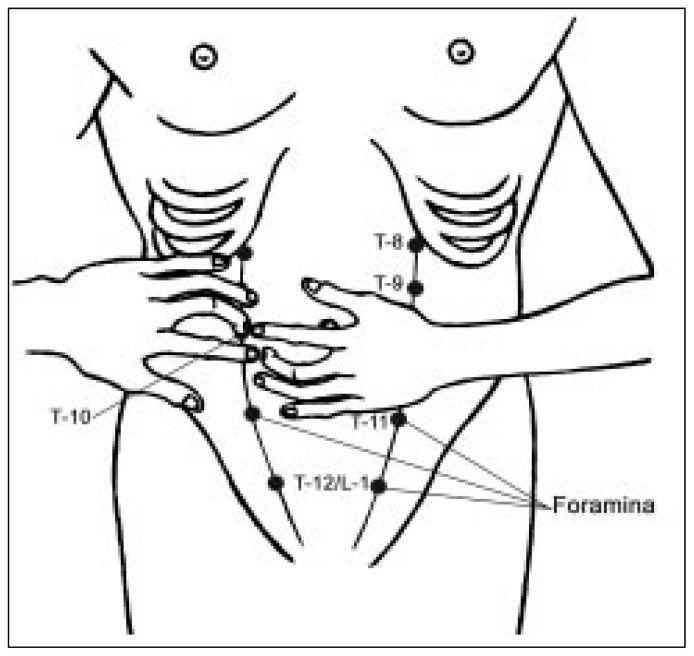

The anterior exits are the easiest to palpate, often best felt with the patient standing and pushing their abdomen outward. T10 is located at the lateral edge of the rectus margin, at the level of the umbilicus. T12/L1 is at the level of the internal inguinal ring. T11 is midway between T10 and T12/L1 at the rectus margin, closer to the midline for these latter two points. T8 is at the junction of the rib margin (eighth rib) and the lateral rectus, and T9 is halfway between T8 and T10. T6 and T7 are located where their respective ribs meet the edge of the rectus muscle.

Lateral muscular foramina are more challenging to palpate and are most easily felt with the patient leaning slightly away from the side being examined. Firmer finger pressure is needed. These openings are in the vertical groove at the junction of the back and abdominal muscles. Lateral T10 is at the point where the 10th rib meets this groove. Lateral L1 can be felt in the groove just above the iliac crest, with the other two lateral branches located in the groove between T10 and L1. It is important not to be discouraged if locating these foramina seems difficult initially; they become more palpable when symptomatic.

Posterior foramina are found in the groove between the paravertebral muscles and the more lateral back muscles. These are also more difficult to palpate, but the muscular depression in this area is more easily identifiable when associated with symptoms and localized tenderness, which is a key aspect of acnes diagnosis.

A description of the tactile sensation of the anterior foramina can aid examiners in locating them. Approaching the opening with a hand resting lightly on the abdomen from the lateral side, the middle fingertip is moved over the rounded edge of the rectus muscle. Here, the examiner may feel an oval-shaped depression, horizontally oriented but sloping posteriorly on the rectus edge at levels T8 through T12/L1. As pressure from the straight finger tuft is gradually increased, the examiner will feel, in succession: 1) firm skin; 2) spongy subcutaneous fat; 3) the oval, firm ring of the aponeurosis containing a morbilliform mass of fat (the fatty plug); and 4) deep to these structures, the firm, round ring that prevents further penetration into the channel. The aponeurotic openings for these nerves can vary in size, from just admitting the fingertip to allowing the entire finger tuft to enter. The deep ring may feel too resistant to push beyond. The fatty plug varies from 2 mm to 2 cm in size, depending on the dilation of the aponeurotic openings. In practice, the aponeurotic openings and the enclosed fatty plug are the most distinguishable from surrounding tissue. These fatty plugs can often be palpated even in asymptomatic individuals and may normally feel uncomfortable to firm palpation, indicating their vulnerability to trauma. The anterior openings of T6, T7, and T8 feel more triangular and are oriented anteroposteriorly across the posteroinferior part of the rib tip. Firmer pressure against the rib tip is necessary to feel these openings. Similar techniques can be used for lateral and posterior openings, which typically only admit 2 mm to 3 mm of the fingertip. Accessory nerve exits are located 2 mm to 3 mm above or below the main branch exits or over adjacent muscle and are usually palpable with certainty only when symptomatic.

The examiner must then confirm that the identified point is indeed a nerve exit and the source of the patient’s pain for accurate acnes diagnosis. With a hand resting gently on the patient’s abdomen lateral to the tender spot, the examiner’s straightened middle finger can be used to displace the patient’s finger medially using small, circular motions. As finger pressure is gradually increased, a patient with ACNES will typically recoil or grab the examiner’s hand, exclaiming, “That’s it!” (Figure 2).9 (Hershfield6 termed this the Hover Sign.) Based on the location of the symptomatic spot and the feel of the muscular foramen, the examiner can confidently ascertain a genuine case of ACNES.

Figure 2.

To further differentiate the pain source, Carnett’s sign should be elicited, a critical step in acnes diagnosis.3 With the patient supine and arms crossed over the chest, they are asked to raise their head or feet off the table while the examiner presses on the tender spot. If splinting the abdominal muscles in this way reduces the pain, the source is likely intra-abdominal. Conversely, if the pain originates from the abdominal wall, splinting the muscles will not reduce the pain and may even intensify it.

The “pinch test”3 can also be used if the pain’s origin side is unclear initially. This involves gently pinching and lifting the skin and subcutaneous fat between the thumb and index finger, first on one side of the abdominal midline and then the other. The patient will indicate if one side is more painful. Cotton and pinprick techniques can assess for hypoesthesia or hyperesthesia around the pain site. Knockhaert23 notes that electromyographic studies of the affected nerve show abnormalities in 60% of studied patients, although he acknowledges the procedure’s low sensitivity. Carnett3 also noted sensitivity along the proximal portion of the affected nerve (Valleix phenomenon). In practice, if tenderness is localized to a palpably identifiable nerve exit, these additional tests, except perhaps Carnett’s sign, are mainly of academic interest in acnes diagnosis.

If doubt persists regarding the acnes diagnosis after these steps, a local anesthetic injection can be diagnostically and therapeutically beneficial (described in “Treatment” section). Complete pain relief following the anesthetic injection confirms the diagnosis.

Recommended Treatment for ACNES

Proper treatment is integral to managing ACNES following acnes diagnosis. A precisely administered local anesthetic injection can completely alleviate ACNES pain. Technique is crucial for both diagnostic confirmation and treatment efficacy. A common mistake is injecting too deeply.

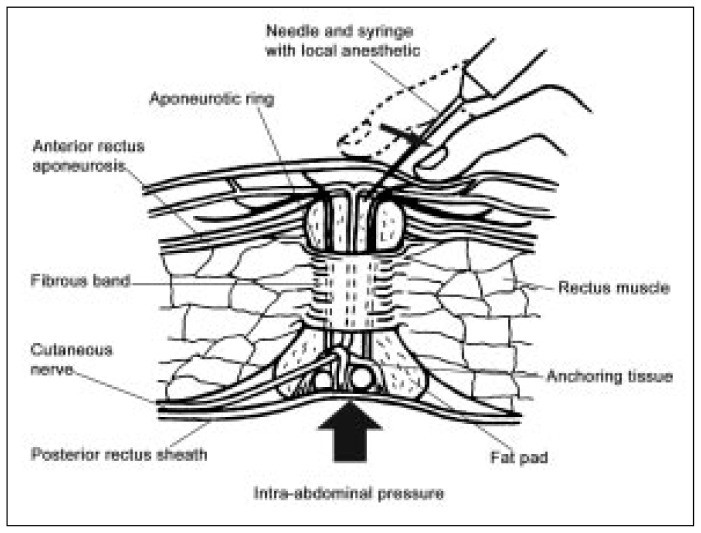

Using a #21 or #22 needle of appropriate length for the subcutaneous tissue thickness (or a #25 or #26 needle if the clinician is highly familiar with the anatomy), 0.5 mL to 1 mL of 2% lidocaine solution (or equivalent) is injected. The larger needle gauge aids in feeling anatomical landmarks during injection, which is important for accurate treatment post acnes diagnosis. For patients with thick adipose tissue, a spinal needle might be necessary to reach the anterior muscle surface.

The injection serves dual purposes: pain relief and reducing herniation of the neurovascular bundle through the fibrous ring. As the needle is inserted, the clinician will feel resistance from the skin, then the non-resistant subcutaneous fat, and finally mild resistance from the aponeurosis and fatty plug. The needle should not be advanced deeper than this level to avoid ecchymosis and increased pressure on the neurovascular bundle within the already constricted fibromuscular channel. At this point, the needle should be centered in the channel and fatty plug, just beneath the aponeurosis. If needle placement is uncertain, it can be withdrawn slightly into the subcutaneous fat for another attempt to position the tip correctly beneath the structures anterior to the fibrous ring.

While landmarks are best palpated with the patient standing and bearing down, and the injection can be administered in this position, it can also be performed with the patient lying down if more comfortable.

To ensure accurate needle placement (Figure 3)24 for injection following acnes diagnosis, the examiner should first place the middle finger of one hand in the aponeurotic opening. Without lifting the finger, the fingertip is moved inferiorly, the skin is cleansed with alcohol using the other hand, and the needle is introduced above the examining fingertip. Once the needle is correctly positioned beneath the aponeurosis, the syringe is stabilized with the same hand used to locate the opening. The patient should be instructed to hold their breath during aspiration and injection. Adhering to these seemingly basic steps is key to successful acnes diagnosis and treatment.

Figure 3.

Patients feeling faint post-injection should lie down until they recover. Otherwise, they should be encouraged to move around. After disposing of the syringe and once the patient has taken a few steps, the clinician should inquire about their pain level. Effective injections often result in patients expressing amazement, “It’s gone!” Clinical response can sometimes take longer if the injection is slightly off-target. If the response is suboptimal and inaccurate placement is suspected, a second injection can be attempted after ten minutes or on a subsequent day. Occasionally, patients report pain relief only upon returning home. In such cases, patients should be advised to return if pain recurs or new symptoms develop.

Mehta4 and McGrady17 utilized a Teflon-coated needle with an exposed tip for nerve location via electrical stimulation. This technique was found cumbersome and time-consuming. Mastering the nerve location method described herein allows for accurate injection placement within minutes, eliminating the need for nerve locators, thus streamlining treatment post acnes diagnosis.

For many patients, a single injection provides lasting relief or enough reassurance that the condition is benign, negating the need for further visits unless pain recurs and another injection is needed. Older patients should be advised to return if pain recurs or if new symptoms arise, to rule out underlying causes. Given the brief procedure time for repeat injections in evaluated patients, same-day appointments can often be scheduled, even for new associated symptoms. Alternatively, scheduling three follow-up appointments spaced a few days apart offers patients the flexibility to cancel if they find they don’t need them. Some patients require multiple injections for complete pain resolution, but rarely more than four or five. Each subsequent injection typically provides progressively longer relief until no further injections are needed. For patients who tolerate local anesthesia well but require frequent injections, alternative treatments exist.

The clinician must assess the need for further evaluation. Are there musculoskeletal conditions (e.g., scoliosis, leg length discrepancy) that might predispose a particular nerve to excessive traction? Especially in older patients, are underlying medical conditions causing abdominal distension? If pain is recurrent or persistent, nerve ablation of the symptomatic portion can be considered. Some ACNES patients have nerve entrapment within an abdominal scar.6,16–18 Excising the scar section or removing sutures around the nerve17 can resolve the issue by relieving both direct nerve compression and distal traction, particularly with differential motion between the abdominal wall and skin. Scar-related nerve entrapment is suggested by pain exacerbation when pinching or moving the scar across underlying muscle. For nerve entrapment under the aponeurosis, phenol or absolute alcohol injections are options. Phenol (5%–7%, 1 mL) has been used,4,12,17 but side effects, including pain and systemic effects, were frequent, possibly due to overly deep injections or phenol itself. In practice, 1 mL of absolute alcohol mixed with 0.5 mL of 2% lidocaine solution has shown good results with minimal local pain. Lidocaine provides immediate relief and prevents alcohol-induced burning sensation, helping confirm correct injection placement. A follow-up phone call a few days later can confirm treatment success. Only rarely is a second alcohol injection needed for partial relief from the first. Surgery is another option, primarily for scar involvement or intolerance to alcohol injection. Surgical procedures should be performed under local anesthesia, allowing patient feedback on nerve traction duplicating symptoms. If so, the nerve should be severed anterior to the muscle to release distal traction.

| Practice Tips for ACNES Diagnosis and Management |

|---|

| Nerve entrapment at the lateral rectus muscle border is the most common cause of abdominal wall pain, a key factor in acnes diagnosis. |

| Ask, “Where exactly is the pain?” and “Show me with one finger” for precise localization in acnes diagnosis. |

| Acnes diagnosis and treatment involve local anesthetic injection into the muscular channel of the affected nerve. |

| Injections serve to relieve pain and reduce neurovascular bundle herniation through the fibrous ring. |

| Precise ice cube application in a thin cloth can act as a local anesthetic and reduce nerve swelling. |

| Elastic bandage application for counterpressure can be beneficial. |

| Heat application may alleviate associated muscle spasms. |

Some researchers7,12,25,26 have advocated adding corticosteroids to local anesthetic injections. While theoretically valuable due to inflammation in ACNES, corticosteroid injections into muscles can cause significant pain, and repeated injections can lead to tissue atrophy. Lidocaine and alcohol injections have been effective in practice, negating the need for corticosteroids in this regimen post acnes diagnosis.

Other modalities can temporarily alleviate ACNES pain. Precise ice cube application wrapped in a thin cloth can act as a local anesthetic and reduce nerve swelling. Elastic bandages for counterpressure and heat applications for muscle spasm relief can also be helpful adjuncts to primary treatment following acnes diagnosis.

These treatment recommendations are broadly applicable to lateral, posterior, and accessory nerves and theoretically to any anatomical area where nerves pass through muscles or tight structures. It is suspected that Janet Travell’s “trigger points”27 are areas where sensory nerves are entrapped in spasming muscles. Acupuncture points may also coincide with nerve exits,13 and limited experience suggests these points can be located by identifying sensitive depressions in underlying muscles, which may be relevant in broader pain management strategies beyond acnes diagnosis specifically.

Summary and Conclusions

For many years, researchers have cautioned against misdiagnosing abdominal wall pain as intra-abdominal pain. The time and resources spent seeking causes within the abdomen, when the issue is literally at the fingertips, are often unwarranted and can cause patient anxiety and unnecessary surgeries. Nerve entrapment at the lateral rectus muscle border is the most common cause of abdominal wall pain, highlighting the importance of accurate acnes diagnosis.

In 1926, Carnett3 termed this condition “intercostal neuralgia.” However, contemporary anatomical and histopathological studies indicate it is primarily nerve entrapment, not inflammation. Thus, Abdominal Cutaneous Nerve Entrapment Syndrome (ACNES) is a more accurate term. Acnes diagnosis and treatment are achieved through local anesthetic injection into the affected nerve’s muscular channel. This article details palpation techniques for identifying muscular neuroforamina and the specific injection procedure. While many publications on abdominal wall pain overlook ACNES, they consistently advise further evaluation for underlying causes if standard treatments fail. This is particularly crucial for older patients. Diagnostic procedures remain a matter of clinical judgment, but early and accurate acnes diagnosis can spare clinicians and patients considerable distress and unnecessary interventions. The information provided herein aims to facilitate early and accurate acnes diagnosis. Srinivasan and Greenbaum22 suggest that ACNES patients without significant relief from local anesthetic injection or other treatments within three months should undergo further evaluation for visceral disease. New symptoms suggestive of visceral disease always warrant further diagnostic investigation, irrespective of ACNES treatment efficacy, ensuring comprehensive patient care following acnes diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The clinical research supporting this review article was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Southern California Permanente Medical Group.

Juan Domingo provided original adaptations of the illustrations.

References

[1] Frank JP. De irritabilitatis legibus in morbis et de peritonitide musculari. In: Delectus opusculorum medicorum antehac in Germaniae diversis academiis editorum. Ticini: Apud Joseph Galeatium; 1792. p. 179–217. [Google Scholar]

[2] Wepfer JJ. Observationes medico-practicae de affectibus capitis internis et externis. Schaffusii: J.J. пальма; 1727. p. 323–4. [Google Scholar]

[3] Carnett JB. Intercostal neuralgia as a cause of abdominal pain and tenderness. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1926 Feb;42(2):625–32. [Google Scholar]

[4] Mehta M, Ranger I. Abdominal wall pain. An overlooked diagnosis. Pain. 1989 Mar;39(2):229–32. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90174-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[5] Applegate WV. Abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. South Med J. 1987 Dec;80(12):1425–8. DOI: 10.1097/00007611-198712000-00001. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[6] Hershfield NB. Abdominal wall pain. Common, but frequently missed. Dig Dis Sci. 1991 Jul;36(7):925–8. DOI: 10.1007/BF01300178. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[7] Swart CM. Injection of painful abdominal scars. Practitioner. 1976 Feb;216(1292):213–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[8] Loos MJ, Scheltinga MR, Mulders LG, Roumen RM. The abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES); a cause of chronic abdominal wall pain. J Pain. 2003 Dec;4(10):530–9. DOI: 10.1016/S1526-5900(03)00714-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[9] Suleiman S, Johnston DE. Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome: a cause of abdominal pain in children. Am J Surg. 2001 Dec;182(6):687–90. DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9610(01)00789-2. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[10] Greenbaum DS. Chronic abdominal wall pain–an underdiagnosed syndrome. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Mar;17(3):231–2. DOI: 10.1016/S0885-3924(98)00161-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[11] Thompson JA, Camilleri M, Fass R, et al. Functional abdominal pain: toward a Rome III consensus. Gut. 2001 Dec;49(Suppl 4):IV55–61. DOI: 10.1136/gut.49.suppl_4.iv55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[12] Lindblom U. Diagnostic blockades in intercostal neuralgia. Acta Med Scand. 1951;139(Suppl 259):1–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[13] Kopell HP, Thompson WA. Peripheral entrapment neuropathies. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1963. p. 3–234. [Google Scholar]

[14] Applegate WV. Abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 1973 Sep;8(3):132–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[15] Asvat Y, Candler P, Chiba T, et al. Illustrated encyclopedic dictionary of medicine. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1988. p. 678. [Google Scholar]

[16] Bonica JJ. Causalgia and other reflex dystrophies. In: Bonica JJ, editor. The management of pain. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1953. p. 134–63. [Google Scholar]

[17] McGrady EM. Abdominal wall pain due to nerve entrapment. In: Reynolds MD, editor. Pain 1987. Proceedings of the VIth World Congress on Pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1987. p. 331–5. [Google Scholar]

[18] Singh R, Kumar A, Singh S, Sharma P. Abdominal wall endometrioma mimicking incisional hernia. Indian J Surg. 2012 Feb;74(1):83–4. DOI: 10.1007/s12262-011-0377-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[19] Bates P, Carson P, Varma V, et al. Diagnostic laparoscopy for chronic pelvic pain: a valuable tool or an expensive placebo? Gut. 1993 Dec;34(12):1781–2. DOI: 10.1136/gut.34.12.1781. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[20] Slocomb JC. Chronic somatic abdominal wall pain. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Sep;46(3):779–95. DOI: 10.1097/00003081-200309000-00022. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[21] Gray DW, Collin J, Collin C, McDonald PJ, Altman DG. Diagnostic laparoscopy in the acute abdomen. World J Surg. 1992 Jan-Feb;16(1):49–53. DOI: 10.1007/BF02067148. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[22] Srinivasan R, Greenbaum DS. Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome: a frequently missed cause of abdominal pain. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Jan 15;136(2):166–7. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00022. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[23] Knockaert DC. Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2002 Oct;23(3):321–2. DOI: 10.1016/S0736-4679(02)00550-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[24] Bonica JJ, Johansen K, Loeser JD. Abdominal pain caused by other diseases. In: Bonica JJ, editor. The management of pain. 2nd ed Vol 2. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1990. p 1254–82. [Google Scholar]

[25] Richelson MA. Steroid injection for abdominal scar pain. Am Fam Physician. 1991 Apr;43(4):1187–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[26] Reynolds J. Abdominal pain in athletes. Phys Sportsmed. 1993 Nov;21(11):53–64. DOI: 10.1080/00913847.1993.11997102. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[27] Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction. The trigger point manual. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1983. p. 67–85.