Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) is a chronic condition characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain accompanied by fatigue, sleep disturbances, and cognitive difficulties. Diagnosing fibromyalgia has historically been challenging due to the lack of objective markers. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has played a crucial role in establishing diagnostic criteria to standardize the assessment of this complex condition. This article delves into the evolution of Acr Fibromyalgia Diagnosis criteria, their strengths, limitations, and the ongoing efforts to refine diagnostic approaches.

The Historical Path to Fibromyalgia Diagnosis

The recognition of fibromyalgia as a distinct medical condition has evolved over centuries. Early descriptions dating back to the 17th century referred to “muscular rheumatism.” In the early 20th century, the term “fibrositis” emerged, focusing on inflammation of fibrous tissues as the cause of pain. However, this theory was later refuted as biopsies failed to show evidence of inflammation.

The term “fibromyalgia” was coined in 1976, marking a shift towards understanding it as a syndrome rather than solely an inflammatory condition. Early diagnostic approaches, such as those by Smythe and Moldofsky in 1977, emphasized non-restorative sleep and tender points. While tender points became a focal point, the lack of clear definitions for other symptoms highlighted the need for more comprehensive and standardized criteria.

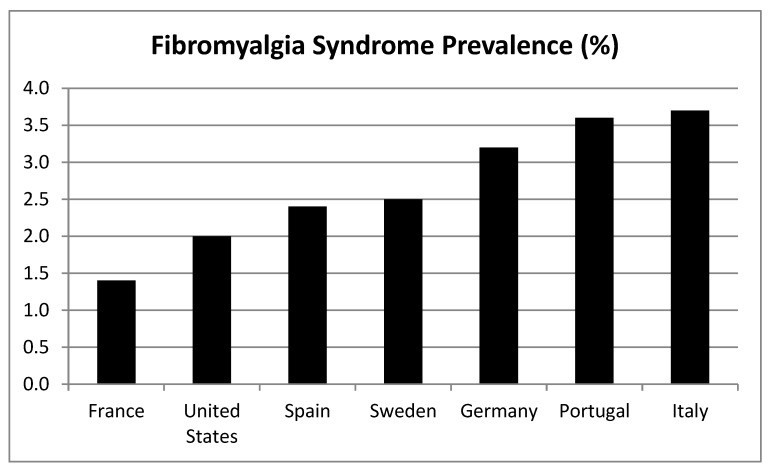

Figure 1. Global Prevalence of Fibromyalgia Syndrome

Image alt text: Global map showing the prevalence of Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) in percentages across different countries, based on data compiled by Cabo-Meseguer et al., highlighting variations in prevalence rates.

In 1987, the American Medical Association officially recognized fibromyalgia as a disease, paving the way for the ACR to develop the first formal diagnostic criteria.

The 1990 ACR Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria: A Landmark Achievement

In 1990, the ACR established the first widely accepted diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. These criteria were based on two key features:

- Widespread Pain History: A history of widespread pain lasting at least 3 months, affecting the axial skeleton and at least three out of four body quadrants.

- Tender Points: Pain in response to digital palpation (approximately 4 kg/cm2 of pressure) in at least 11 out of 18 specified tender point sites.

Figure 2. ACR 1990 Fibromyalgia Tender Point Locations

Image alt text: Illustration depicting the 18 tender point locations on the human body as defined by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1990 criteria for fibromyalgia diagnosis, visualized on a figure inspired by “The Three Graces”.

The 1990 ACR criteria were instrumental in legitimizing fibromyalgia as a medical condition. They provided a standardized approach for diagnosis, facilitating research and improving clinical understanding. The World Health Organization (WHO) also recognized fibromyalgia in 1992, further solidifying its status as a recognized disease.

However, the 1990 criteria also faced criticisms. The reliance on tender points was seen as subjective and difficult to standardize in clinical practice. Important symptoms like fatigue, sleep problems, and cognitive dysfunction were not explicitly included. Furthermore, the “all or nothing” approach of the criteria failed to capture the spectrum of fibromyalgia severity.

The 2010 ACR Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria: Shifting Focus to Symptom Severity

Recognizing the limitations of the 1990 criteria, the ACR introduced revised diagnostic criteria in 2010. These new criteria moved away from the tender point count and focused on patient-reported symptoms using two scales:

- Widespread Pain Index (WPI): Measures pain across 19 body areas. Patients indicate areas where they have experienced pain in the past week (score range 0-19).

Figure 3. Body Regions for Widespread Pain Index (WPI)

Image alt text: Diagram outlining the 19 body areas included in the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) scale, part of the 2010 ACR diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia, used to assess the extent of pain distribution.

- Symptom Severity (SS) Scale: Assesses the severity of fatigue, unrefreshed sleep, and cognitive symptoms. It also includes a checklist of somatic symptoms. (score range 0-12).

Fibromyalgia diagnosis based on the 2010 ACR criteria requires fulfilling one of the following conditions, with symptoms present for at least 3 months:

- WPI ≥ 7 and SS ≥ 5

- WPI between 3 and 6 and SS ≥ 9

While the 2010 criteria eliminated the need for tender point examination and incorporated a broader range of symptoms, they were still intended for physician assessment, limiting their use in large-scale studies. Criticisms also arose regarding the subjectivity of physician-based symptom evaluation and the absence of tender point assessment.

Refinements: The 2011 and 2016 ACR Fibromyalgia Criteria Proposals

To address the limitations of the 2010 criteria, particularly for epidemiological research and community studies, further revisions were proposed in 2011 and 2016.

The 2011 criteria modified the Symptom Severity Scale to be patient-administered, replacing the physician’s somatic symptom checklist with self-reported assessments of headache, abdominal pain/cramps, and depression symptoms. This adaptation aimed to facilitate self-reporting and large-scale data collection.

The 2016 criteria sought to unify the 2010 and 2011 versions into a single set applicable for both clinical and research settings. Key changes included:

- Generalized Pain Criterion: Refined the widespread pain definition to require pain in at least four out of five regions (four quadrants and axial pain), excluding jaw, chest, abdominal, headache, and facial pain from regional definitions to better differentiate fibromyalgia from regional pain syndromes.

- Combined Criteria: Integrated the WPI and SS scales from the 2010 criteria with the generalized pain criterion.

Figure 4. Evolution of ACR Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria

Image alt text: Timeline illustrating the history and development of Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) Diagnostic Criteria from early concepts to the ACR 2016 proposal, highlighting key milestones and revisions.

The 2016 proposal emphasized that fibromyalgia diagnosis is valid regardless of other co-existing conditions, moving away from the exclusionary approach of earlier criteria. It aimed to capture central pain perception and distress more effectively than the 1990 criteria, which primarily focused on peripheral allodynia (tender points).

Tools for Assessment: Polysymptomatic Distress Scale (PDS) and Fibromyalgia Survey Questionnaire (FSQ)

Building upon the 2010 ACR criteria, the Polysymptomatic Distress Scale (PDS), also known as the Fibromyalgianess Scale (FS) or central sensitivity score, was developed. The PDS is calculated by summing the WPI and SS scores (range 0-31) and provides a continuous measure of fibromyalgia severity. It can categorize patients into severity levels from “none” to “very severe.” While a PDS score of 12 or higher is suggestive of fibromyalgia, the diagnostic criteria (2010 or 2011) are still recommended for individual diagnosis, with PDS used for severity assessment and monitoring treatment effects.

The Fibromyalgia Survey Questionnaire (FSQ) was designed as a self-report tool for epidemiological studies. It incorporates elements of the WPI and SS, along with questions about fatigue, cognitive issues, unrefreshed sleep, and somatic symptoms. While validated for research, the FSQ is not recommended for self-diagnosis or as a replacement for physician assessment.

Impact of Diagnostic Criteria on Prevalence and Sex Ratio

The choice of diagnostic criteria significantly impacts reported fibromyalgia prevalence rates. The 1990 criteria, considered more stringent, tend to identify a more severely affected patient population. Studies using the 1990 criteria often report higher WPI and SS scores in recruited patients compared to studies using the 2010 criteria.

Interestingly, the sex ratio in fibromyalgia diagnosis is also influenced by the criteria used. The 1990 ACR criteria historically led to a much higher female-to-male ratio (around 13.7:1). However, with the 2010 and 2011 criteria, this ratio has narrowed (4.8:1 and 2.3:1 respectively). This shift suggests that the 1990 tender point-based criteria might have been biased towards women, who tend to be more sensitive to pressure pain. More recent research indicates that the perception of fibromyalgia as predominantly a women’s disease is not entirely accurate, and unbiased studies using validated criteria suggest a female proportion closer to 60%.

Validity and Limitations of ACR Fibromyalgia Diagnosis Criteria

The ACR fibromyalgia criteria have demonstrated good validity in distinguishing fibromyalgia from other rheumatic conditions like rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA). The 1990 criteria showed a sensitivity of 88.4% and specificity of 81.1% in differentiating fibromyalgia from other rheumatic conditions. The 2010 criteria improved these figures, reporting a sensitivity of 96.6% and specificity of 91.8% in discriminating fibromyalgia from RA and OA.

Despite their validity, the ACR criteria are not without limitations. A significant concern is the potential for misdiagnosis in the general population. Overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis remain challenges, potentially leading to inappropriate treatment. Many clinicians still rely on digital palpation rather than systematically applying ACR criteria, contributing to inconsistencies in diagnosis. Furthermore, current criteria may not adequately account for psychological, environmental, and sociocultural factors that play a crucial role in fibromyalgia.

New Directions in Fibromyalgia Diagnosis

Recognizing the ongoing challenges, new diagnostic approaches are being explored. The ACTTION-APS Pain Taxonomy (AAPT) has proposed an alternative dimensional diagnostic system for fibromyalgia. This system conceptualizes fibromyalgia across five dimensions:

- Core Diagnostic Criteria: Pain in six or more body sites, sleep disturbance, and fatigue.

- Common Features: Tenderness, cognitive dysfunction, musculoskeletal stiffness, and environmental sensitivities.

- Comorbidities: Common medical and psychiatric conditions often associated with fibromyalgia.

- Neurobiological, Psychosocial, and Functional Consequences: Impact on function, disability, and quality of life.

- Putative Mechanisms, Risk Factors, and Protective Factors: Underlying biological and psychosocial factors.

This AAPT proposal aims to provide a more comprehensive and nuanced diagnostic framework, incorporating risk factors, prognosis, and pathophysiology. However, these criteria are still under validation, and their feasibility and accuracy are yet to be fully established.

The Future of ACR Fibromyalgia Diagnosis

Advancements in fibromyalgia diagnosis are crucial to improve patient care and reduce the healthcare burden associated with this condition. Addressing gender biases in diagnosis and refining diagnostic criteria to be more objective and comprehensive are key priorities. There is a growing need for:

- Revision of ACR Criteria: A re-evaluation of the 2010 ACR criteria, considering the 2016 proposal and incorporating new research findings.

- Improved Physician Training: Ensuring healthcare professionals are trained in utilizing official diagnostic criteria and recognizing the multifaceted nature of fibromyalgia.

- Objective Markers: Exploring and integrating objective measures related to fibromyalgia pathophysiology, such as central sensitization assessments like Slowly Repeated Evoked Pain (SREP), to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Combining such objective measures with symptom-based questionnaires may offer a more robust diagnostic approach.

Conclusion: Moving Towards More Accurate and Holistic Fibromyalgia Diagnosis

While the ACR fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria have significantly advanced the understanding and management of this condition, challenges remain. Despite the 2010 criteria and subsequent proposals, dissatisfaction persists among healthcare professionals and patients regarding diagnostic practices. Misdiagnosis remains a significant concern, and current criteria could better incorporate the complex interplay of psychological, environmental, and sociocultural factors in fibromyalgia. Continued research, refinement of diagnostic tools, and enhanced physician education are essential to achieve more accurate, holistic, and patient-centered fibromyalgia diagnosis and care.

Author Contributions

C.M.G.-S. conceived the original idea with G.A.R.d.P., both authors designed the search, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities co-financed by FEDER funds [RTI2018-095830-B-I00], and an FPU pre-doctoral contract from the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport [FPU2014-02808]. The APC was funded by FEDER funds [RTI2018-095830-B-I00].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.