Acute limb ischemia (ALI) represents a critical medical emergency characterized by a sudden reduction in blood flow to a limb, posing an immediate threat to limb viability. This abrupt interruption of arterial supply can rapidly lead to tissue damage and functional impairment within a matter of hours, underscoring the urgency of prompt diagnosis and intervention. The incidence of acute limb ischemia is estimated to be approximately 1.5 cases per 10,000 individuals annually. Understanding the differential diagnosis of acute limb ischemia is paramount for timely and accurate management.

Etiology of Acute Limb Ischemia

Acute limb ischemia arises from several distinct etiologies, broadly categorized into three primary groups:

- Embolism: This is the most frequent cause, where a thrombus or embolus originating from a proximal source, such as the heart or a proximal artery, travels downstream and lodges in a more distal artery, obstructing blood flow. Common sources include atrial fibrillation, mural thrombi post-myocardial infarction, and aneurysms.

- Thrombosis in situ: In this scenario, a thrombus forms directly within a limb artery, often at the site of a pre-existing atherosclerotic plaque. Plaque rupture triggers thrombus formation, acutely occluding the artery. This can manifest as acute ischemia or an acute exacerbation of chronic limb ischemia.

- Trauma: Less commonly, acute limb ischemia can result from traumatic injury to limb arteries, including direct arterial injury, compression, or compartment syndrome, which indirectly compromises arterial flow.

Clinical Features: The 6 Ps of Acute Limb Ischemia

The classic clinical presentation of acute limb ischemia is famously described by the “6 Ps”, which are crucial for rapid clinical assessment:

- Pain: Sudden onset of limb pain, often severe and disproportionate to examination findings initially.

- Pallor: The affected limb appears pale or white due to reduced arterial blood supply.

- Pulselessness: Absence of palpable pulses distal to the arterial occlusion. Comparing to the contralateral limb is essential.

- Paresthesia: Numbness, tingling, or altered sensation in the limb, indicating nerve ischemia.

- Perishingly Cold (Poikilothermia): The ischemic limb feels significantly colder to the touch compared to the unaffected limb.

- Paralysis: Muscle weakness or inability to move the limb, a late and severe sign indicating advanced ischemia and potential irreversible damage.

The abrupt onset of these symptoms is a hallmark of acute limb ischemia. The presence of normal pulses in the contralateral limb is a significant indicator of an embolic occlusion. Patient history should explore potential embolic sources, including pre-existing chronic limb ischemia, atrial fibrillation, recent myocardial infarction, abdominal aortic aneurysms, and peripheral aneurysms.

Delayed presentation to medical care increases the risk of irreversible neuromuscular damage (typically after 6 hours of symptom onset), potentially leading to limb paralysis and poorer outcomes. The Rutherford classification system (Table 1) categorizes acute limb ischemia severity, guiding management decisions and predicting prognosis.

| Category | Prognosis | Sensory Loss | Motor Deficit | Arterial Doppler | Venous Doppler |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I – Viable | No Immediate threat | None | None | Audible | Audible |

| IIA – Marginally Threatened | Salvageable, if promptly treated | Minimal (toes) or none | None | Inaudible | Audible |

| IIB – Immediately Threatened | Salvageable if immediately revascularised | More than toes, rest pain | Mild/Moderate | Inaudible | Audible |

| III – Irreversible | Major tissue loss, permanent nerve damage inevitable | Profound | Profound, paralysis | Inaudible | Inaudible |

Table 1 – Clinical Categories of Acute Limb Ischemia, adapted from Rutherford et al., 2009

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Limb Ischemia

Accurate differential diagnosis is crucial in cases presenting with acute limb symptoms to ensure appropriate and timely intervention. Conditions that may mimic acute limb ischemia include:

- Critical Limb-Threatening Ischemia (CLTI): While CLTI also represents severe peripheral artery disease, it is a chronic condition characterized by gradual symptom onset, often with rest pain, ulcers, or gangrene, rather than the sudden onset seen in ALI. Distinguishing between acute-on-chronic limb ischemia and acute ischemia can be challenging but is crucial for management strategies.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Phlegmasia Cerulea Dolens: Extensive DVT, particularly phlegmasia cerulea dolens, can cause severe limb pain, swelling, and cyanosis (bluish discoloration), potentially mimicking ALI. However, in DVT, pulses are typically present, and the limb is often warm and swollen rather than pale and cold. Phlegmasia alba dolens, another form of severe DVT, presents with limb swelling and pallor but also with preserved pulses. Doppler ultrasound can readily differentiate between arterial occlusion and venous thrombosis.

- Peripheral Neuropathy and Nerve Compression: Conditions like acute nerve compression or severe peripheral neuropathy can cause limb pain, paresthesia, and even weakness, but typically lack the acute onset pallor, pulselessness, and coldness characteristic of ALI. Neurological examination and pulse assessment are key differentiating factors.

- Spinal Cord Compression: While less common in mimicking unilateral ALI, spinal cord compression can present with bilateral limb weakness and sensory changes. However, it typically lacks the acute vascular signs of ALI. Neurological examination and imaging of the spine would be necessary to differentiate.

- Musculoskeletal Pain: Severe muscle strains, compartment syndrome of non-vascular origin, or other musculoskeletal injuries can cause acute limb pain, but they do not present with the vascular signs (pallor, pulselessness, coldness) of ALI. Compartment syndrome secondary to reperfusion injury is a complication of ALI, but primary musculoskeletal compartment syndrome is a separate entity in the differential.

Investigation of Acute Limb Ischemia

Prompt investigation is essential to confirm the diagnosis and guide management of acute limb ischemia.

- Initial Bedside Doppler Ultrasound: This is the initial diagnostic tool of choice, readily available and non-invasive. It can quickly assess arterial and venous flow in both limbs, identifying the presence and location of arterial occlusion and helping to exclude DVT.

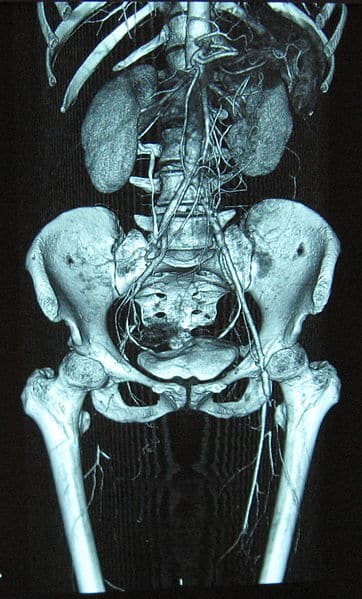

- CT Angiography (CTA): If ALI is suspected and limb salvage is considered possible, CTA is the gold standard imaging modality. It provides detailed anatomical information about the arterial tree, precisely locating the occlusion and assessing collateral circulation. This information is crucial for surgical planning, determining the optimal operative approach (e.g., femoral vs. popliteal incision).

- Routine Blood Tests: These include serum lactate levels to assess the degree of tissue ischemia, and a thrombophilia screen may be considered, especially in younger patients or those with no clear embolic source, to investigate underlying hypercoagulable states. An electrocardiogram (ECG) is important to evaluate for atrial fibrillation as a potential embolic source.

Figure 2 – Reconstructed 3D CT angiogram, showing complete occlusion of the right femoral artery, diagnostic imaging for acute limb ischemia.

Figure 2 – Reconstructed 3D CT angiogram, showing complete occlusion of the right femoral artery, diagnostic imaging for acute limb ischemia.

Management of Acute Limb Ischemia

Acute limb ischemia demands immediate and decisive management to restore limb perfusion and prevent irreversible tissue damage.

Initial Management

ALI is a surgical emergency. Irreversible tissue damage can occur within 6 hours of complete arterial occlusion. Therefore, rapid senior surgical consultation is paramount.

Initial steps include:

- High-flow oxygen administration to maximize oxygen delivery to ischemic tissues.

- Establishment of adequate intravenous access for fluid resuscitation and medication administration.

- Anticoagulation: Immediate initiation of therapeutic dose heparin or intravenous heparin infusion to prevent thrombus propagation and further embolization.

Conservative Management

Conservative management with anticoagulation alone may be considered in patients with Rutherford category 1 and 2a ischemia, where limb viability is not immediately threatened. Prolonged heparin therapy may be effective in non-operatively managing selected cases.

Patients managed conservatively require frequent monitoring, including serial clinical assessments and measurement of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) to ensure therapeutic anticoagulation. Surgical intervention is indicated if clinical improvement is not observed.

Surgical Intervention

Surgical intervention is mandatory for Rutherford category 2b and 3 acute limb ischemia, where the limb is immediately threatened or irreversible ischemia has developed.

Surgical options depend on the etiology of ALI:

- Embolic Occlusion:

- Embolectomy: Surgical removal of the embolus using a Fogarty catheter, often performed with radiological guidance.

- Local Intra-arterial Thrombolysis: Delivery of thrombolytic agents directly into the occluded artery to dissolve the thrombus.

- Bypass Surgery: If embolectomy or thrombolysis is unsuccessful, or in cases of underlying arterial disease, bypass surgery may be necessary to restore blood flow around the occlusion. This is also considered if there is insufficient backflow after embolectomy or to address occluded popliteal aneurysms.

- Thrombotic Occlusion:

- Local Intra-arterial Thrombolysis: Similar to embolic occlusion, thrombolysis can be used to dissolve in-situ thrombus.

- Angioplasty: Balloon angioplasty, often combined with thrombolysis, to dilate the stenotic or occluded artery and restore flow.

- Bypass Surgery: May be required if angioplasty and thrombolysis are insufficient to restore adequate perfusion.

Intra-arterial thrombolysis can be time-consuming and is often reserved for Rutherford 2a cases where immediate surgical embolectomy is not feasible within the critical 6-hour window.

Irreversible Limb Ischemia: In cases of irreversible ischemia (Rutherford category 3), characterized by mottled, non-blanching skin and woody muscles, urgent amputation is often necessary. Palliative care may be considered in select circumstances.

Post-revascularization, patients require intensive monitoring, often in a high dependency unit (HDU), due to the risk of ischemia-reperfusion syndrome.

Long-Term Management

Long-term management focuses on reducing cardiovascular mortality risk and preventing recurrent ischemic events. This includes:

- Lifestyle Modifications: Encouraging regular exercise, smoking cessation, and weight loss as needed.

- Antiplatelet or Anticoagulant Therapy: Most patients are started on long-term antiplatelet agents (e.g., low-dose aspirin, clopidogrel) or anticoagulation (e.g., warfarin, DOACs), depending on the underlying etiology and risk factors.

- Management of Predisposing Conditions: Addressing underlying conditions that contributed to ALI, such as uncontrolled atrial fibrillation or hypercoagulable disorders.

- Rehabilitation: Patients undergoing amputation require comprehensive occupational therapy and physiotherapy, with a long-term rehabilitation plan and potential transfer to a rehabilitation center.

Complications of Acute Limb Ischemia

Acute limb ischemia carries a significant mortality rate, approximately 20%, with a 30-day mortality rate of around 15% following surgical treatment.

Reperfusion Injury is a major complication following revascularization. The sudden restoration of blood flow to ischemic tissue can paradoxically cause further damage due to increased capillary permeability and release of toxic metabolites. Complications of reperfusion injury include:

- Compartment Syndrome: A frequent complication after ALI revascularization. Swelling within muscle compartments increases pressure, compromising tissue perfusion. Prophylactic fasciotomies (surgical release of muscle compartments) are often performed during revascularization surgery to mitigate this risk. Clinical signs include calf swelling and severe pain with passive muscle movement. Untreated compartment syndrome leads to muscle necrosis.

- Systemic Metabolic Derangements: Release of intracellular contents from damaged muscle cells into the systemic circulation can cause:

- Hyperkalemia: Elevated potassium levels due to cellular release.

- Acidosis: Increased hydrogen ion concentration due to anaerobic metabolism.

- Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Kidney Injury (AKI): Release of myoglobin from damaged muscle can precipitate in the renal tubules, causing AKI.

Close monitoring for compartment syndrome and reperfusion injury is crucial post-revascularization. Electrolyte imbalances and AKI may require aggressive medical management, including continuous renal replacement therapy (hemofiltration).

Key Points in Acute Limb Ischemia Management

- Acute limb ischemia typically presents with sudden onset pain and pallor, most commonly due to acute thrombus-in-situ or embolization.

- CT angiography is the gold-standard investigation to confirm diagnosis and guide management.

- Treatment options are diverse, tailored to the underlying cause, anatomical location of occlusion, and patient comorbidities.

- Vigilant monitoring for reperfusion syndrome is essential in all cases post-revascularization.