Feeling acute pain, whether from a sudden injury or illness, is an experience everyone dreads. As авто repair experts transitioning into health content creation for “xentrydiagnosis.store,” we understand the importance of precision, thoroughness, and providing solutions. Just as we meticulously diagnose and repair vehicles, nurses expertly diagnose and manage patient pain. This guide provides a detailed nursing care plan for acute pain, incorporating the Acute Pain Nursing Diagnosis Nanda, to equip nurses with the tools to effectively alleviate patient discomfort and promote recovery.

Drawing parallels to our automotive expertise, diagnosing acute pain is akin to identifying the root cause of a car malfunction. Accurate assessment is crucial before implementing effective repairs – or in this case, interventions. This comprehensive resource will delve into the nuances of acute pain, offering a structured approach to assessment, diagnosis using NANDA, planning, intervention, and evaluation. Whether it’s administering medication, employing non-pharmacological techniques, or providing crucial emotional support, this guide aims to enhance your ability to manage acute pain effectively and improve patient outcomes.

Let’s explore how to provide exceptional care for patients experiencing acute pain, focusing on the acute pain nursing diagnosis NANDA framework. This guide will serve as a cornerstone in developing robust nursing care plans and interventions.

Understanding Acute Pain

Pain is a multifaceted, subjective experience shaped by a complex interplay of physical, emotional, and psychological factors. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.” This definition highlights that pain is not merely a physical sensation but also carries significant emotional and psychological weight.

Adding to this understanding, Margo McCaffery, a pioneering nurse expert in pain management, offered a profoundly influential definition: “pain is whatever the person says it is and exists whenever the person says it does.” This emphasizes the highly subjective nature of pain; the patient’s perception is paramount.

“Pain is whatever the person says it is and exists whenever the person says it does.”

Margo McCaffery – Pain Management Nurse Pioneer

Acute pain, in the context of acute pain nursing diagnosis NANDA, is defined as pain lasting less than three months, where relief is generally anticipated and predictable. This contrasts with chronic pain, which persists for more than three months and often lacks a predictable endpoint. Acute pain arises from the body’s physiological response to noxious stimuli, serving a protective function by alerting the individual to injury or illness. This sudden onset of pain prompts the patient to seek help, support, and relief.

Factors such as cultural background, emotional state, and psychological or spiritual distress can also influence the experience of acute pain. In older adults, pain assessment can be particularly challenging due to potential cognitive impairment and sensory deficits. Therefore, a thorough assessment and appropriate nursing diagnosis of acute pain, guided by frameworks like NANDA, are central to effective care planning. This care plan will focus on the assessment and management of the acute pain nursing diagnosis NANDA.

Common Causes of Acute Pain

Understanding the causes of acute pain is essential for accurate nursing diagnosis. Here are several common causes and related factors:

- Tissue Damage: This includes surgical incisions, traumatic injuries, fractures, and burns.

- Inflammation: Conditions like appendicitis, pancreatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease lead to tissue swelling and pain.

- Nerve Damage: Neuropathic pain can result from conditions such as sciatica, shingles, or nerve compression.

- Psychological Conditions: Stress and anxiety can manifest as headaches or muscle tension, contributing to acute pain.

- Procedural Pain: Medical procedures, injections, and post-operative recovery can all induce acute pain.

Recognizing Signs and Symptoms of Acute Pain

Identifying the signs and symptoms of acute pain is crucial for effective acute pain nursing diagnosis NANDA. These manifestations, both subjective and objective, guide the nursing assessment process.

Subjective Data

Subjective data relies on the patient’s self-report, which is paramount in pain assessment.

- Pain Reports Using Scales: Patients describe their pain intensity using numeric rating scales (0-10), Wong-Baker FACES scale, or verbal descriptor scales.

- Pain Description: Patients articulate the quality of their pain, such as aching, burning, stabbing, throbbing, or sharp.

- Verbal Complaints of Pain: Direct statements from the patient expressing their pain experience.

- Family/Caregiver Reports: In cases where the patient cannot fully communicate, family members or caregivers may report observed pain indicators or behavioral changes.

Objective Data

Objective data are observable signs that indicate the presence of pain.

- Guarding Behavior: Protecting the painful area, avoiding movement, or assuming a guarded posture.

- Facial Mask of Pain: Grimacing, wincing, furrowed brow, clenched teeth.

- Expressions of Pain: Restlessness, moaning, crying, groaning, irritability.

- Autonomic Responses: Physiological changes due to pain, including:

- Sweating (diaphoresis)

- Changes in vital signs (increased blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate)

- Pupil dilation (mydriasis)

Nursing Diagnosis: Acute Pain (NANDA-I)

Following a thorough assessment, formulating a nursing diagnosis is the next critical step. For acute pain, the NANDA-I (North American Nursing Diagnosis Association International) diagnosis is commonly used. “Acute Pain” as a NANDA nursing diagnosis is defined as: “Sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage; sudden or slow onset of any intensity from mild to severe with an anticipated or predictable end and a duration of less than 3 months.”

While NANDA nursing diagnoses provide a standardized framework for care, it’s important to remember that clinical judgment and individual patient needs are paramount. The nurse’s expertise shapes the care plan, prioritizing each patient’s unique situation. Accurate acute pain nursing diagnosis NANDA is the foundation for developing an effective and personalized pain management plan.

Goals and Expected Outcomes for Acute Pain Management

Setting realistic and measurable goals is crucial in the nursing care plan for acute pain nursing diagnosis NANDA. Expected outcomes should be patient-centered and focus on pain relief and improved function.

- Effective Pain Management Techniques: Patient demonstrates appropriate use of diversional activities and relaxation techniques to manage pain.

- Satisfactory Pain Control: Patient reports pain is controlled to a satisfactory level, ideally rating pain at or below 3-4 on a 0-10 pain scale.

- Improved Physiological Well-being: Patient exhibits stable vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, respirations) at baseline levels and displays relaxed muscle tone or body posture.

- Utilization of Pain Relief Strategies: Patient effectively uses both pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain relief strategies.

- Enhanced Mood and Coping: Patient demonstrates improved mood and coping mechanisms related to pain management.

Related Nursing Care Plans

The acute pain nursing diagnosis NANDA is relevant across a wide range of medical conditions and situations. Related nursing care plans might address the underlying causes of pain, such as:

- Post-operative pain management

- Pain related to fractures or trauma

- Pain associated with inflammatory conditions (arthritis, appendicitis)

- Pain management in cancer patients

Nursing Assessment for Acute Pain: A Detailed Approach

A comprehensive nursing assessment is the cornerstone of effective pain management and accurate acute pain nursing diagnosis NANDA. Nurses play a pivotal role in pain assessment. Here are key assessment techniques:

Perform a Comprehensive Pain Assessment

1. Conduct a thorough pain assessment: Determine the location, characteristics, onset, duration, frequency, quality, and severity of pain.

The patient is the most reliable source of information about their pain. Self-reporting is the gold standard in pain assessment. Interviewing the patient allows them to describe their pain experience in their own words, providing essential details about location, intensity, and duration. This information is vital for developing optimal pain management strategies.

Utilize the “PQRST” mnemonic as a guide during pain assessment:

- P – Provoking Factors: “What makes your pain better or worse?” Identify triggers or alleviating factors.

- Q – Quality (Characteristic): “Tell me what it’s exactly like. Is it a sharp pain, throbbing pain, dull pain, stabbing, etc.?” Determine the nature of the pain.

- R – Region (Location): “Show me where your pain is.” Pinpoint the exact location(s) of pain.

- S – Severity: Ask the patient to rate their pain using different pain rating methods (e.g., Pain scale of 0-10, Wong-Baker Faces Scale). Quantify pain intensity.

- T – Temporal (Onset, Duration, Frequency): “Does it occur all the time or does it come and go? When did it start? How long does it last?” Understand the pain pattern over time.

Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)

The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) is a widely used pain assessment tool suitable for adults and children over seven who can understand and use numbers to rate their pain intensity.

How to Use:

- Explain the Scale: Say to the patient: “Please rate your pain on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means ‘no pain’ and 10 means ‘the worst pain you can imagine.’”

- Assessment: Ask: “What number between 0 and 10 best describes your pain right now?”

- Document the Response: Record the number provided by the patient.

Interpretation:

- 0: No pain.

- 1–3: Mild pain.

- 4–6: Moderate pain.

- 7–10: Severe pain.

Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale

The Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale is designed for children over three years old and adults who may have difficulty expressing pain verbally. It utilizes facial expressions to represent pain intensity.

How to Use:

- Present the Scale: Show the patient the Wong-Baker FACES chart.

- Explain the Scale: Say to the patient: “These faces show how much something can hurt. The face on the left means no pain, and the faces show more and more pain up to the face on the right, which shows the worst pain possible.”

- Assessment: Ask the patient: “Point to the face that shows how much you hurt right now.”

- Document the Response: Record the number corresponding to the selected face (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10).

Interpretation:

- 0: No pain.

- 2: Hurts a little bit.

- 4: Hurts a little more.

- 6: Hurts even more.

- 8: Hurts a whole lot.

- 10: Hurts worst.

FLACC Scale

The FLACC Scale is an observational tool used to assess pain in infants and children aged 2 months to 7 years, or in individuals who cannot communicate pain verbally.

How to Use:

- Observation: Observe the patient unobtrusively for 1–5 minutes.

- Scoring: Assign a score of 0, 1, or 2 for each category (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability).

- Total Score: Add scores for a total between 0 and 10.

| Criteria | 0 POINTS | 1 POINT | 2 POINTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Face | No particular expression or smile. | Occasional grimace or frown; withdrawn; disinterested. | Frequent to constant frown, clenched jaw, quivering chin. |

| Legs | Normal position or relaxed. | Uneasy, restless, tense. | Kicking or legs drawn up. |

| Activity | Lying quietly, normal position, moves easily. | Squirming, shifting back and forth, tense. | Arched, rigid, or jerking. |

| Cry | No cry (awake or asleep). | Moans or whimpers; occasional complaint. | Crying steadily, screams or sobs; frequent complaints. |

| Consolability | Content, relaxed | Reassured by occasional touching, hugging, or being talked to; distractible. | Difficult to console or comfort. |

Interpretation:

- 0: Relaxed and comfortable.

- 1–3: Mild discomfort.

- 4–6: Moderate pain.

- 7–10: Severe discomfort/pain.

PAINAD Scale

The PAINAD Scale is specifically designed to assess pain in patients with advanced dementia who cannot verbally communicate their pain effectively.

How to Use:

- Observation: Observe the patient during rest and activity.

- Scoring: Score each of the five categories (Breathing, Negative Vocalization, Facial Expression, Body Language, Consolability) from 0 to 2.

Categories and Scoring:

| Criteria | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breathing (Independent of Vocalization) | Normal breathing. | Occasional labored breathing; short periods of hyperventilation. | Noisy labored breathing; long periods of hyperventilation; Cheyne-Stokes respirations |

| Negative Vocalization | None. | Occasional moan or groan; low-level speech with a negative or disapproving quality. | Repeated troubled calling out; loud moaning or groaning; crying. |

| Facial Expression | Smiling or inexpressive. | Sad, frightened, frowning. | Facial grimacing. |

| Body Language | Relaxed. | Tense, distressed pacing, fidgeting. | Rigid, fists clenched, knees pulled up, pulling or pushing away. |

| Consolability | No need to console. | Distracted or reassured by voice or touch. | Unable to console, distract, or reassure. |

Interpretation:

- Higher scores indicate more severe pain.

2. Assess pain location: Ask the patient to point to the site of discomfort.

Body charts or drawings can be helpful tools for patients to indicate specific pain locations. For patients with limited vocabulary, pinpointing the location is crucial, especially in pediatric assessments.

3. Obtain a pain history:

Gather information about: (1) effectiveness of previous pain treatments; (2) medications taken and timing; (3) current medications; (4) allergies or medication side effects.

4. Determine the patient’s perception of pain:

Allow the patient to describe their pain experience in their own words. Ask questions like, “What does having this pain mean to you?” or “How is this pain affecting you specifically?” to understand their perspective.

5. Screen for pain with vital signs:

Many healthcare facilities recognize pain assessment as the “fifth vital sign,” integrating it into routine vital signs monitoring.

6. Initiate pain assessments proactively:

Recognize that pain responses are individual. Some patients may be hesitant to report pain unless directly asked.

7. Utilize the Wong-Baker FACES Rating Scale when appropriate:

For patients who may struggle with numerical scales (e.g., children, language barriers), the Wong-Baker FACES scale can be a more effective tool.

Determine Factors Contributing to Acute Pain

8. Investigate associated signs and symptoms:

A thorough assessment of pain includes considering related signs and symptoms to gain a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s pain experience. Sometimes, patients may minimize or overlook the presence of pain.

9. Assess patient’s expectations for pain relief:

Understand the patient’s goals for pain management. Some may seek complete pain elimination, while others may be satisfied with reduced pain intensity. This influences treatment expectations and engagement.

10. Evaluate willingness to explore pain control techniques:

Assess the patient’s openness to various pain management methods, including non-pharmacological approaches, as some patients may prefer traditional medication-based treatments. Combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies can often be most effective.

11. Identify factors that alleviate pain:

Ask patients about any methods they use to relieve pain, such as meditation, deep breathing, prayer, heat or cold application, or specific positions. Incorporate these alleviating activities into the care plan.

Determine Patient’s Response to Pain

12. Evaluate patient response to pain and management strategies:

Help patients objectively describe the effectiveness of pain relief measures, minimizing the influence of mood, emotion, or anxiety. Discrepancies between behavior and reported pain relief may indicate coping mechanisms rather than actual pain reduction.

13. Allocate sufficient time for patient pain reports:

Recognize that patients may hesitate to report pain due to perceived time constraints on staff. Minimize interruptions during pain assessments to ensure thorough evaluation and management.

14. Explore the meaning of pain for the patient:

Understand what pain signifies to the individual, as this can significantly impact their response. For some, especially those nearing end-of-life, suffering may hold spiritual meaning.

15. Regularly reassess and document pain levels:

Reassess and document pain levels after initiating pain management plans, with each new pain report, and before and after administering analgesics. Consistent reassessment ensures treatment effectiveness and allows for timely adjustments. Reassessment frequency should be guided by pain stability and institutional policies, ranging from every 10 minutes in acute phases to every 4-8 hours for stable conditions.

Nursing Interventions for Acute Pain Management

As nurses, our role is to treat patients experiencing pain with empathy and effective interventions, regardless of the perceived “reality” of their pain. The following therapeutic nursing interventions are essential for managing acute pain nursing diagnosis NANDA:

Provide proactive pain relief:

Administer analgesics before pain becomes severe or before painful procedures. Preemptive analgesia, for instance, involves giving pain medication before surgery to minimize post-operative pain. This approach is also beneficial before procedures like wound dressing changes, physical therapy, or postural drainage.

Acknowledge and validate patient pain:

Always ask patients about their pain and believe their reports. Dismissing or questioning their pain can damage the nurse-patient relationship, hindering pain management and rapport.

Implementing Non-Pharmacologic Pain Management Strategies

Integrate non-pharmacologic methods:

Incorporate techniques such as guided relaxation, deep breathing exercises, and music therapy into the patient’s pain management plan. Non-pharmacologic approaches encompass physical, cognitive-behavioral, and lifestyle strategies.

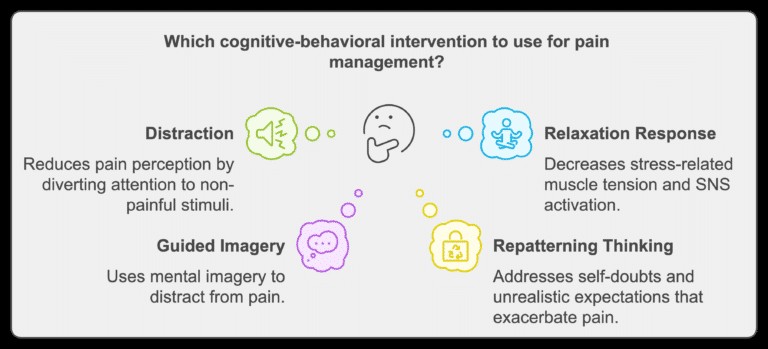

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Pain Management:

CBT techniques aim to provide comfort by altering psychological responses to pain.

- Distraction: Focuses attention on non-painful stimuli to reduce pain awareness. Examples include reading, watching TV, playing games, or guided imagery.

- Eliciting the Relaxation Response: Stress intensifies pain by increasing muscle tension and activating the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Relaxation techniques counteract these effects. Examples include directed meditation, music therapy, and deep breathing exercises.

- Guided Imagery: Uses mental images or guided visualization to distract from pain.

- Repatterning Unhelpful Thinking: Addresses negative self-beliefs or unrealistic expectations that can worsen pain and hinder effective pain management.

- Other CBT Techniques: Reiki, spiritual approaches, emotional counseling, hypnosis, biofeedback, and progressive relaxation.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Interventions for Pain Management

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Interventions for Pain Management

Cutaneous Stimulation and Physical Interventions:

Cutaneous stimulation offers temporary pain relief by distracting from painful sensations through tactile input.

- Massage: If appropriate, massage can interrupt pain transmission, increase endorphin release, and reduce tissue edema. It promotes relaxation and decreases muscle tension by improving local circulation. Avoid massage in areas of skin breakdown, suspected clots, or infections.

- Heat and Cold Applications: Cold reduces pain, inflammation, and muscle spasms by decreasing pain chemical release and nerve impulse conduction. Use cold primarily in the first 24 hours after injury. Heat is better for chronic pain, improving blood flow and reducing pain reflexes.

- Acupressure: Applies finger pressure to specific points, similar to acupuncture points, to relieve pain.

- Contralateral Stimulation: Stimulating the skin opposite to the painful area, useful when the painful site cannot be directly touched.

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS): Delivers low-voltage electrical stimulation to pain areas or along pain-innervating pathways.

- Immobilization: Restricting movement of a painful body part using splints or supports can provide relief. Prolonged immobilization can lead to muscle atrophy, contractures, and cardiovascular issues, so follow agency protocols.

- Other Cutaneous Stimulation Interventions: Therapeutic exercises (tai chi, yoga, low-intensity exercises, ROM exercises), and acupuncture.

Assess response to non-pharmacologic interventions:

Regularly evaluate the effectiveness of non-pharmacologic methods to guide adjustments and optimize pain management.

Integrate patient-preferred non-pharmacologic methods:

Incorporate patient preferences into daily care, such as warm compresses or positioning for comfort, alongside pharmacological treatments.

Providing Pharmacologic Pain Management

Administer pharmacologic pain management as prescribed:

Pharmacologic pain management involves opioids, nonopioids (NSAIDs), and co-analgesic drugs.

The World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder provides a stepwise approach to pain management, particularly for cancer pain, aligning analgesic choice with pain intensity.

- Step 1 (Mild Pain, 1-3 rating): Nonopioid analgesics (acetaminophen, NSAIDs) with or without co-analgesics.

- Step 2 (Moderate Pain, 4-6 rating): Opioid or opioid/nonopioid combination, with or without co-analgesics.

- Step 3 (Severe Pain, 7-10 rating): Opioid, titrated in scheduled doses until pain relief is achieved.

Administer nonopioids:

Nonopioids like acetaminophen and NSAIDs (aspirin, ibuprofen) work peripherally, blocking prostaglandin synthesis and reducing nociceptor stimulation. Effective for mild to moderate pain, they have anti-inflammatory (except acetaminophen), analgesic, and antipyretic effects. NSAIDs have a ceiling effect, beyond which increased dosage doesn’t improve analgesia and may increase toxicity risk.

Common NSAID side effects include heartburn and stomach upset. Patients should take NSAIDs with food and a full glass of water to minimize GI irritation.

Common NSAIDs include:

- Aspirin: Prolongs bleeding time; discontinue a week before surgery. Avoid in children under 12 due to Reye’s syndrome risk. Can interact with warfarin, increasing anticoagulation.

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol): Potential for hepatotoxicity and renal toxicity with high doses or long-term use. Limit daily intake to 3 grams.

- Celecoxib (Celebrex): COX-2 inhibitor with fewer GI side effects than COX-1 NSAIDs.

Administer opioids as prescribed:

Opioids are indicated for severe pain and can be given orally, IV, via PCA systems, or epidurally.

Administer co-analgesics (adjuvants) as prescribed:

Co-analgesics enhance pain relief, manage related discomforts, improve analgesic effectiveness, or reduce side effects.

- Antidepressants: Improve pain relief, mood, and reduce excitability.

- Local Anesthetics: Block pain signal transmission in specific nerve distribution areas.

- Other Co-analgesics: Anxiolytics, sedatives, antispasmodics, stimulants, laxatives, and antiemetics.

Utilize a multimodal approach:

Multimodal analgesia combines two or more methods or drugs to enhance pain relief, reducing reliance on opioids alone. Combining analgesics, adjuvants, and procedures targets different pain pathways, often synergistically. This allows for lower doses of each medication, minimizing side effects.

Administer analgesia before painful procedures:

Prevent procedure-related pain by administering analgesics beforehand (e.g., before wound care, venipunctures, chest tube removal, suctioning).

Perform nursing care during peak analgesic effect:

Oral analgesics peak around 60 minutes, IV analgesics around 20 minutes. Scheduling nursing tasks during peak effect maximizes patient comfort and care compliance.

Evaluate analgesic effectiveness and side effects:

Individual patient responses to analgesics vary due to differences in absorption and metabolism. Regularly assess pain relief and monitor for side effects.

Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA) Management

Educate patients on PCA use:

Instruct patients on self-administration, emphasizing dose control and pressing the button only when needed. Patient education is crucial for effective and safe PCA use.

Monitor sedation and respiratory status:

Closely monitor sedation level and respiratory rate, especially if a basal infusion rate is used. This helps detect over-sedation or respiratory depression early.

Prevent PCA by proxy:

Instruct staff, family, and visitors not to press the PCA button for the patient. Only the patient should control PCA administration.

Assess cognitive and physical ability to use PCA:

Regularly assess the patient’s ability to safely and effectively use the PCA device.

Educate about Authorized Agent Controlled Analgesia (AACA):

For patients unable to use PCA independently, educate patients and authorized family members about AACA.

Adjust basal rate promptly if needed:

Reduce or discontinue basal infusion if increased sedation or respiratory changes occur.

Document and reassess pain frequently:

Document pain levels before and after PCA administration to evaluate effectiveness and guide adjustments.

Pediatric Pain Management Considerations

Children require specialized pain management approaches.

- Use age-appropriate pain scales: FLACC scale for infants, Wong-Baker FACES for children over three.

- Weight-based medication dosing: Administer pain medications based on weight and developmental level, following pediatric guidelines.

- Avoid contraindicated medications: Avoid aspirin in children under 12 due to Reye’s syndrome risk.

- Distraction techniques: Use toys, games, or videos during painful procedures.

- Encourage parental involvement: Parental presence provides comfort and security.

- Age-appropriate explanations: Explain procedures using simple language and visual aids.

Geriatric Pain Management Considerations

Older adults are more sensitive to medications and may have communication challenges.

- Use appropriate pain assessment tools: Consider sensory or cognitive impairments when selecting assessment tools.

- Start with lower analgesic doses: Initiate therapy with lower doses and titrate slowly, monitoring for side effects. Older adults are more susceptible to side effects of analgesics and adjuvants.

- Acetaminophen as first-line for mild pain: Use acetaminophen for mild musculoskeletal pain due to lower risk profile compared to NSAIDs.

- Monitor for NSAID-induced GI toxicity: Assess GI risk and consider COX-2 selective NSAIDs or nonselective NSAIDs with GI protection if needed.

- Consider opioids over NSAIDs for high-risk patients: Opioids may be safer than NSAIDs in older adults at high risk for GI complications.

- Educate patients and caregivers: Educate about potential side effects of NSAIDs and opioids, including GI distress and sedation.

- Review medications for interactions: Minimize polypharmacy risks by reviewing all medications.

- Gentle physical therapies: Implement massage or warm compresses, ensuring skin integrity.

- Address sensory impairments: Face the patient, speak clearly, and ensure use of hearing or vision aids.

Pain Management for Patients with Cognitive Impairments

- Observational pain scales: Use PAINAD scale or similar tools for non-verbal patients.

- Observe non-verbal pain cues: Look for facial grimacing, agitation, or behavioral changes.

- Consistent caregivers: Provide care from familiar staff to reduce anxiety.

- Simplify communication: Use short sentences, clear instructions, and visual cues.

- Involve family/caregivers: Seek input from family to understand patient behaviors and preferences.

Avoiding Placebos in Pain Management

- Avoid placebos: Placebo use is unethical and undermines patient trust.

- Educate healthcare team: Educate about ethical and legal issues of deceptive placebo use.

- Validate patient pain reports: Accept patient reports of pain regardless of physical findings.

- Evidence-based pain management: Use personalized, evidence-based strategies instead of placebos.

For further interventions related to pain, please consult the Chronic Pain Nursing Care Plan.

Recommended Resources

Recommended nursing diagnosis and nursing care plan books and resources (affiliate links):

Ackley and Ladwig’s Nursing Diagnosis Handbook: An Evidence-Based Guide to Planning Care

Nursing Care Plans – Nursing Diagnosis & Intervention (10th Edition)

Nurse’s Pocket Guide: Diagnoses, Prioritized Interventions, and Rationales

Nursing Diagnosis Manual: Planning, Individualizing, and Documenting Client Care

See also

Other recommended site resources for this nursing care plan:

References

Suggested resources for further understanding of acute pain nursing diagnosis NANDA and care plans: