Introduction

Inpatient Rehabilitation Facilities (IRFs) operate under strict guidelines from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to qualify for Medicare reimbursement. A cornerstone of these regulations is the “60% rule,” stipulating that sixty percent of an IRF’s admitted patients must have one of 13 specific medical conditions. These conditions, often referred to as the Acute Rehab 13 Diagnosis criteria, include stroke, spinal cord injury, congenital deformity, amputation, major multiple trauma, hip fracture, brain injury, burns, active polyarthritis, systemic vasculitis with joint involvement, specified neurologic conditions, severe osteoarthritis, and hip or knee replacement under certain complex conditions. Beyond diagnosis, patients must participate in an intensive, multidisciplinary rehabilitation program, typically involving at least 3 hours of therapy per day for 5 out of 7 consecutive days – the well-known “3-hour rule.” This translates to 900 minutes of therapy over 7 days for patients who cannot meet the daily 3-hour requirement due to limitations like low endurance. Qualifying therapies include physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), speech and language pathology (SLP), and orthotic and prosthetic services. Furthermore, IRF patients require specialized nursing care, regular physician oversight by a rehabilitation specialist (at least 3 times weekly), case management services, and weekly interdisciplinary team conferences led by a physician. Admission to an IRF necessitates the reasonable expectation of patient benefit from this intensive therapy, supported by daily and team conference notes documenting functional improvement. [1,2]

The origin of the 3-hour therapy requirement traces back to consultant recommendations to the Health Care Financing Administration. [3] Critically, this benchmark was established without robust, objective evidence definitively proving that 3 hours of daily therapy is either essential or sufficient for optimal outcomes in IRFs. Several studies have since examined the validity of this regulation. Wang et al. investigated stroke rehabilitation outcomes in 360 patients, finding better outcomes in patients receiving 3 hours of daily therapy compared to those receiving less. [3] Conversely, Johnston and Miller’s study, comparing IRF patients pre- (1982) and post- (1983) 3-hour rule implementation, observed a 0.55-hour daily therapy time increase post-rule, without any corresponding functional improvement or reduced length of stay (LOS). [4] Foley et al.’s literature review on therapy time in IRFs concluded a lack of sufficient evidence to support the 3-hour daily or 900-minute weekly therapy mandate. [5]

Alt text: Patient demographics table comparing consistent and non-consistent therapy groups in an inpatient rehabilitation facility, showing no significant differences in age, sex, or admission FIM score.

The 3-hour rule is uniformly applied, regardless of patient age, diagnosis upon admission (including those within the acute rehab 13 diagnosis categories or otherwise), functional status, or co-existing health conditions. It overlooks the potential need for other crucial services within IRFs, such as mental health support, specialized physician consultations, wound care, nutritional guidance, and intensive registered nurse care, which may be less accessible in skilled nursing facilities or home care settings. Third-party payers frequently utilize the 3-hour rule to justify pre-authorization denials for IRF admissions and, along with recovery audit contractors, to retroactively deny payment for IRF-level care.

This study aims to determine if patients at a specific medical center who adhered to the 3-hour therapy rule demonstrated superior outcomes compared to patients in the same program who, during at least one 7-day period, did not meet this therapy duration threshold.

Methods

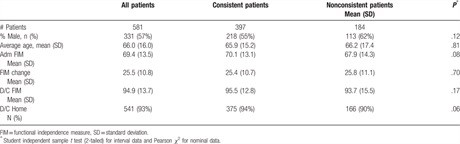

This retrospective study analyzed data from the quality improvement records of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Patient records were reviewed for all admissions to an IRF between September 1, 2013, and December 31, 2015. Patients staying less than the minimum time for analysis were excluded. Patients were categorized into two groups: a “consistent” group, who received at least 900 minutes of therapy per week for every week of their IRF stay, and a “non-consistent” group, who failed to meet this threshold in at least one week.

Statistical analysis was performed to compare these groups. The Student’s t-test assessed differences in total Functional Independence Measure (FIM) score change and FIM change per day between the consistent and non-consistent groups. The relationship between group consistency and discharge to home was evaluated using contingency tables and the Pearson chi-square test. Therapy minutes per day were compared using a two-sample t-test. The impact of sex on functional change was also analyzed using a two-sample t-test. Linear regression analysis explored the relationship between daily therapy minutes and both total FIM change and FIM change per day, as well as the association between daily therapy minutes and LOS. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare LOS between the consistent and non-consistent groups and to examine the relationship between daily therapy minutes and discharge to home. Comorbidity tiers were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Finally, multiple linear regression analysis assessed FIM score improvement as a function of age, sex, admission FIM score, comorbidity tier, admitting diagnosis (including consideration of acute rehab 13 diagnosis categories), and group consistency (consistent vs. non-consistent).

Alt text: Diagnostic groups table showing the distribution of patients with stroke, joint replacement, and complex medical/surgical conditions across consistent and non-consistent therapy groups in inpatient rehabilitation.

Results

The study included 581 patients (see Table 1). 397 patients (the consistent group) met the 3-hour rule therapy requirements throughout their IRF stay. 184 patients (the non-consistent group) had at least one week with less than 900 minutes of therapy. The consistent group averaged 154.0 minutes of therapy per day, while the non-consistent group averaged 137.5 minutes daily. Patients with stroke were more likely to be in the consistent group, whereas patients with joint replacements and those admitted post-complex medical/surgical care were less likely to be consistent (see Table 2). No significant differences were found between the groups regarding age, sex, admission FIM score (Table 1), or comorbidity score. Importantly, the consistent group did not demonstrate better outcomes in discharge FIM score, FIM score change, LOS, or discharge to home (Table 1).

Regression analysis examining the relationship between daily therapy minutes and FIM improvement (total and per day) found no significant association (Figures 1 and 2). Similarly, no association was found between daily therapy minutes and LOS (Figure 3). Counterintuitively, patients with fewer daily therapy minutes showed greater FIM improvement per day (P = .02) and shorter LOS (P < .001). However, the low r-squared values (1.6% for FIM/day and 5.4% for LOS) indicate that therapy time explains only a small fraction of the outcome variation, suggesting other factors are more influential. Comorbidity tier analysis showed no significant differences between the consistent and non-consistent groups.

Alt text: Boxplot visualizing the change in Functional Independence Measure (FIM) scores, comparing the distribution of functional improvement between consistent and non-consistent therapy groups in inpatient rehabilitation.

Alt text: Regression analysis graph depicting FIM change per day against minutes per day of therapy, illustrating the lack of a strong positive correlation between therapy intensity and functional gains in inpatient rehabilitation.

Alt text: Regression analysis graph showing Length of Stay (LOS) in days versus minutes per day of therapy, demonstrating no significant reduction in hospital stay with increased therapy intensity in inpatient rehabilitation.

Multiple linear regression analysis revealed no significant relationship between FIM improvement and comorbidity tier or adherence to the 3-hour rule (P = 0.546), nor with sex (P = 0.302). FIM improvement did correlate with age (P < .001) and admission FIM score (P < .001), with younger age and lower admission FIM scores predicting greater improvement. Patients with joint replacements within the acute rehab 13 diagnosis group showed significantly greater improvement than patients in other diagnostic categories.

Regression analysis of FIM change per day versus therapy minutes per day indicated a trend towards greater FIM change per minute per day in orthopedic, joint replacement, and complex medical/surgical groups compared to the stroke group, although this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 4).

Alt text: Scatterplot illustrating FIM change per day against minutes per day of therapy, highlighting the variability in functional improvement rates across different therapy intensities in inpatient rehabilitation.

Discussion

The IRF staff in this study prioritized providing all patients with adequate and intensive therapy programs. The average therapy time difference between the consistent and non-consistent groups was only 18.5 minutes per day, suggesting both groups received substantial therapy. Similar to Johnston and Miller’s findings [4], this study did not establish the 3-hour daily or 900-minute weekly therapy threshold as necessary or directly associated with improved function. Multiple linear regression confirmed that age, admission FIM score, and total joint replacement diagnosis – within the spectrum of acute rehab 13 diagnosis – significantly correlated with FIM improvement. Younger patients generally exhibit better recovery from illness and within IRF settings [7]. A ceiling effect on FIM improvement is also recognized [8]; patients discharged at a higher functional level may exhibit less overall improvement compared to those admitted with lower function who have greater potential for gain. Total joint replacement, a procedure with generally favorable outcomes [9], further explains the improved outcomes in this diagnostic group.

Interestingly, regression analysis showed that the non-consistent group had shorter LOS and greater FIM improvement per day. However, the low R-squared values suggest factors beyond therapy time are primary drivers of these variations. The non-consistent group had a higher proportion of patients admitted after total joint replacement (8.7% vs. 4.3%) and a trend towards lower admission FIM scores (67.9 vs. 70.1; P=0.08), which likely contributed to the observed outcome differences.

Conversely, the consistent group had a higher percentage of stroke patients (30.5% vs. 13.6%) and significantly more stroke patients compared to complex medical/surgical and joint replacement groups (P = .001). Stroke patients also trended towards less FIM change per day relative to therapy minutes compared to these other diagnostic groups, further contributing to outcome differences between the consistent and non-consistent groups.

Existing literature supports the general principle of exercise as beneficial for rehabilitation, improving strength, endurance, coordination, and functional abilities [10]. However, Wade and de Jong [11] highlight the absence of studies defining the minimum effective therapy time or the maximum time beyond which benefit plateaus. Keith [12]’s review on treatment intensity in rehabilitation suggests mixed evidence for a direct intensity-outcome relationship. Some studies indicate increased therapy time reduces LOS and improves function. Roach et al. [13] found a correlation between physical therapy minutes and discharge functional status in orthopedic patients. Kirk-Sanchez and Roach [14] showed increased therapy time related to improved discharge function in orthopedic surgery IRF patients. DiSotto-Monastero et al. [15] reported reduced LOS with increased therapy frequency (7 days/week vs. 5 days/week) but no functional improvement change in a diverse IRF population. Hughes et al. [16] and Rapoport and Judd-Van Eerd [17] similarly found reduced LOS with 7-day/week therapy in joint replacement and mixed stroke/orthopedic populations, respectively. Qu et al.’s [18] analysis of spinal cord injury data revealed a therapy time-functional improvement link. Dumas et al. [19] in pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) and Spivak et al. [21] in adult TBI also reported positive associations between therapy intensity and functional gains. Slade et al. [20] found enhanced therapy reduced LOS without impacting functional improvement in neurologic patients. Peiris et al. [22] demonstrated that 7-day/week therapy improved function and reduced LOS compared to 5-day/week therapy in Australian IRFs. Cifu et al. [23] reported therapy intensity linked to motor function improvement, but not cognitive function or LOS, in TBI patients within Model TBI Systems.

However, contrasting studies show no significant relationship between increased therapy time and better outcomes. Ruff et al. [24] found no difference in function or LOS with 7-day vs. 6-day/week therapy post-stroke. Horn et al. [25] observed minimal contribution of therapy minutes to TBI patient outcomes. Heinemann et al. [26] found no therapy time-functional improvement correlation in TBI and spinal cord injury patients. Keren et al. [27] similarly found no such relationship in stroke patients.

Significant differences exist between IRFs and subacute units. IRFs offer on-site access to specialized physicians and diagnostic technologies for complex medical issues, generally not available in subacute settings. IRFs also maintain higher nurse-to-patient and registered nurse-to-total nurse ratios [28], factors linked to improved patient outcomes [29]. Furthermore, IRFs may provide greater access to psychiatric, psychological, and clinical nurse specialist support to address therapy refusal behaviors.

Patients have diverse rehabilitation needs. For some, gym-based PT/OT time is paramount. For others, comprehensive medical management is crucial. Still others benefit most from specialized nursing for skin care, bowel/bladder management, or behavioral issues, or from counseling services. While PT, OT, and SLP time is easily quantifiable, the value of enhanced physician and nursing services in IRFs is harder to measure.

Post-acute care decisions are often driven by the 60% and 3-hour rules. The 60% rule is largely opinion-based [30]. This study, along with Johnston and Miller’s [4], finds no evidence that 3-hour rule-consistent treatment leads to superior outcomes compared to slightly less intensive therapy. Wang et al. [3] did report better outcomes with 3-hour rule adherence in stroke patients, a discrepancy possibly explained by their stroke-specific population and higher average speech therapy time. This study and Johnston and Miller’s included broader IRF admissions, potentially diluting the effect in specific subgroups like stroke.

Courts have ruled against denying IRF access based solely on the 3-hour rule. Hooper versus Sullivan established that IRF admission should be deemed necessary if a coordinated, multi-service program at an intensity unattainable at home or in skilled nursing facilities is required. In 2018, CMS clarified to Medicare contractors that reimbursement denial based solely on therapy time thresholds is inappropriate [31].

Conclusion

This study and literature review align with the federal court ruling: evidence does not support the 3-hour daily therapy requirement as a rigid criterion for IRF admission or continued stay. Patient evaluation should be individualized, considering diagnosis (including relevance to acute rehab 13 diagnosis categories), functional level, age, comorbidities, and the need for medical and nursing services beyond lower care settings. The 3-hour rule’s uniform application to diverse patient populations with varying needs is a critical limitation.

This study’s retrospective design at a single IRF is a limitation. Ethical and regulatory hurdles complicate randomized prospective studies of varying therapy times. Comorbidity tiers and admission FIM scores were used to control for medical complexity, with Shih et al. [32] validating admission FIM as a strong predictor of medical stability. Future research focusing on therapy time needs for patients requiring two versus three therapies, and diagnosis-specific therapy time requirements, would be valuable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: George P Forrest.

Formal analysis: George P Forrest.

Investigation: George P Forrest, Alycia Horn, Mina Kodsi.

Methodology: George P Forrest.

Project administration: George P Forrest.

Software: Mina Kodsi, Joshua Smith.

Writing – original draft: George P Forrest, Joshua Smith.

Writing – review & editing: George P Forrest, Mina Kodsi.

George P Forrest orcid: 0000-0002-3648-417X.

References

[1]. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual Chapter 1 section 110 retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/manuals/downloads/bp102c01pdf. Accessed on December 9, 2018.

[2]. Medicare Learning Network retrieved at https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/Inpatient_Rehab_Fact_Sheet. Accessed August 20, 2018.

[3]. Wang H, Camicia M, Terdiman J, et al. Daily treatment time and functional gains of stroke patients during inpatient rehabilitation. PM&R 2013;5:122–8.

[4]. Johnston MV, Miller LS. Cost effectiveness of the Medicare three-hour regulation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1986;67:581–5.

[5]. Foley N, Pereira S, Salter K, et al. Are recommendations regarding inpatient therapy intensity following acute stroke really evidenced based? Top Stroke Rehabil 2012;19:96–102.

[6]. CMS Rehabilitation facility tier comorbidity updates 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/Downloads/2016-06-16-IRF-Tier-Comorbidity.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2018.

[7]. Everink IH, van Haastregt JC, van Hoof SJ, et al. Factors influencing discharge after inpatient rehabilitation of older patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2016;16: doi:1186/s12877-016-0187-4.

[8]. Forrest G, Deike D. The impact of inpatient rehabilitation on outcome for patients with cancer. J Community Support Oncology 2018;16:e138–44.

[9]. DeJong G, Tian W, Smout RJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of joint replacement rehabilitation patients discharged from skilled nursing and inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90:1306–16.

[10]. CDC Physical Activity Basics retrieved at https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pa-health/accessed 8/208/20/2018.

[11]. Wade DT, de Jong BA. Recent advances in rehabilitation. BMJ 2000;320:1385–8.

[12]. Keith RA. Treatment strength in rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:1298–304.

[13]. Roach KE, Ally D, Finnerty B, et al. The relationship between the duration of physical therapy services in the acute care setting and change in functional status with lower-extremity orthopedic problems. Phys Ther 1998;78:19–24.

[14]. Kirk-Sanchez NJ, Roach KE. Relationship between duration of therapy services in a comprehensive rehabilitation program and mobility at discharge in patients with orthopedic problems. Phys Ther 2011;81:888–95.

[15]. DiSotto-Monastero M, Chen X, Fish S, et al. Efficacy of 7 days per week inpatient admissions and rehabilitation therapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:2165–9.

[16]. Hughes K, Kuffner L, Dean B. Effect of weekend physical therapy on postoperative length of stay following total hip and total knee arthroplasty. Physiother Can 1993;45:245–9.

[17]. Rapoport J, Judd-Van Eerd M. Impact of physical therapy weekend coverage on length of stay in an acute care community hospital. Phys Ther 1989;69:32–7.

[18]. Qu H, Shewchuk RM, Yu-ying C, et al. Evaluating quality of acute rehabilitation care for patients with spinal cord injury: an extended Donabedian model. Qual Manag Health Care 2010;19:47–61.

[19]. Dumas HM, Haley SM, Carey TM, et al. The relationship between functional mobility and the intensity of physical therapy intervention in children with traumatic brain injury. Pediatr Phys Ther 2004;16:157–64.

[20]. Slade A, Tennant A, Chamberlain A. A randomized controlled trial to determine the effect of intensity of therapy upon length of stay in a neurological rehabilitation setting. J Rehabil Med 2002;34:260–6.

[21]. Spivak G, Spettell CM, Ellis DW, et al. Effects of intensity of treatment and length of stay on rehabilitation outcomes. Brain Inj 1992;5:419–34.

[22]. Peiris CL, Sheilds N, Brusco NK, et al. Additional Saturday rehabilitation improves functional independence and quality of life and reduces length of stay: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med 2013;11:198.

[23]. Cifu DX, Kreutzer JS, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, et al. The relationship between therapy intensity and rehabilitative outcomes after traumatic brain injury: a multicenter analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:1441–8.

[24]. Ruff RM, Yarnell S, Marinos JM. Are stroke patients discharged sooner if in-patient rehabilitation services are provided seven v six days per week? Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1999;78:143–6.

[25]. Horn SD, Corrigan JD, Beaulieu CL, et al. TBI patient, injury, therapy, and ancillary treatments associated with outcomes at discharge and 9 months post discharge. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96(8 suppl):S304–29.

[26]. Heineman AW, Hamilton B, Linacre JM, et al. Functional status and therapeutic intensity during inpatient rehabilitation. Am J of Phys Med and Rehabil 1995;74:315–26.

[27]. Keren O, Motin M, Heinemann AW, et al. Relationship between rehabilitation therapies and outcome of stroke patients in Israel: a preliminary study. Isr Med Assoc J 2004;6:736–41.

[28]. Jung HY, Li Q, Rahman M, et al. Medicare Advantage enrollee’s use of nursing homes: trends and nursing home characteristics. Am J of Man Care 2018;24:e349–256.

[29]. Nelson A, Powell-Cope G, Palacios P, et al. Nurse staffing and patient outcomes in inpatient rehabilitation settings. Rehabil Nurs 2007;32:179–202.

[30]. Reinstein L. The history of the 75-percent rule: three decades past and an uncertain future. PM&R 2014;6:973–5.

[31]. Medicare Advocacy retrieved at Http://Www.Medicareadvocacy.Org/Cms-Clarifies-3-Hour-Rule-Should-Not-Preclude-Medicare-Covered-Inpatient-Rehabilitation-Hospital-Care. Accessed on 12/11/201830.

[32]. Shih SL, Zafonte R, Bates DW, et al. Functional status outperforms comorbidities as a predictor of 30-day acute care readmissions in the inpatient rehabilitation population. J of Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:921–6.

Keywords: inpatient rehabilitation facilities; outcomes; three -hour rule

Copyright © 2019 the Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.