Introduction

Adie’s pupil, clinically known as tonic pupil, is a neurological condition affecting the pupil of the eye. Predominantly observed in young women, it often manifests unilaterally, where one pupil is noticeably larger than the other. A key characteristic is the diminished or absent pupillary light reflex in the affected eye. Intriguingly, the affected pupil demonstrates hypersensitivity to dilute pilocarpine solutions, a diagnostic marker. While the exact causes of Adie’s pupil are multifaceted and sometimes elusive, research indicates associations with various underlying health conditions, ranging from infections to autoimmune disorders. Accurate Adie’s pupil diagnosis is crucial to differentiate it from other pupillary abnormalities and to identify potential underlying systemic diseases. This article will explore the clinical features, diagnostic approaches, and differential diagnoses of Adie’s pupil, providing a comprehensive understanding of this condition.

Understanding the Basics of Pupillary Reflexes

To appreciate Adie’s pupil, it’s essential to understand normal pupillary function. The pupil’s size is dynamically controlled by two muscles: the pupillary sphincter and the pupillary dilator. Parasympathetic nerve fibers innervating the sphincter cause pupillary constriction (miosis), while sympathetic nerve fibers innervating the dilator cause dilation (mydriasis) [1]. Two primary reflexes govern pupillary size:

- Light Reflex: When light shines into one eye, both pupils constrict. This involves both a direct response (in the illuminated eye) and a consensual response (in the opposite eye).

- Accommodation Reflex (Near Reflex): When shifting focus from a distant to a near object, both pupils constrict, aiding in clear near vision [2].

Adie’s pupil disrupts these normal reflexes, leading to characteristic pupillary abnormalities.

What is Adie’s Pupil?

Adie’s pupil, also known as tonic pupil, was first described by British neurologist William John Adie in 1931 [3]. It is characterized by:

- Pupil Dilation (Mydriasis): Often unilateral, the affected pupil is larger than the normal pupil (anisocoria). In about 80% of cases, only one eye is involved [4].

- Diminished or Absent Light Reflex: The direct and consensual pupillary light reflexes are weakened or absent in the affected eye.

- Slow Accommodation Reflex: The pupil reacts slowly and tonically (hence “tonic pupil”) to accommodation.

- Pilocarpine Supersensitivity: The affected pupil constricts excessively to weak pilocarpine solutions (e.g., 0.025% to 0.125%), while a normal pupil shows minimal response.

Adie’s pupil typically presents in young adults, predominantly women, with onset between 20 and 40 years of age. Patients may notice the difference in pupil size when looking in a mirror. While often an isolated finding, it can be associated with other conditions. When combined with diminished or absent deep tendon reflexes, it’s termed Adie syndrome or Holmes-Adie syndrome [5]. If accompanied by reduced reflexes and segmental anhidrosis (lack of sweating), it is known as Ross syndrome [6]. The complexity of its etiology can make Adie’s pupil diagnosis and identification of related underlying conditions challenging.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

Patients with Adie’s pupil may present with a range of symptoms, or sometimes be asymptomatic, noticing the condition incidentally. Common symptoms include:

- Blurred Vision: This is the most frequent symptom, reported by 65% of patients in a literature review [7–42]. Blurred vision often arises from accommodative dysfunction due to ciliary muscle involvement.

- Photophobia (Light Sensitivity): Experienced by about 15% of patients, this occurs because the larger pupil allows more light to enter the eye.

- Diplopia (Double Vision): Less common, affecting around 12.5% of patients, diplopia can result from associated neurological issues or accommodative problems.

- Pain Behind the Eyeball: A less frequent symptom, reported by approximately 5% of patients.

- Asymptomatic Presentation: Around 30% of patients may have no noticeable ophthalmologic symptoms and the condition is discovered during routine examination or incidentally.

Key Diagnostic Features of Adie’s Pupil

The hallmark features of Adie’s pupil, crucial for Adie’s pupil diagnosis, are visually and pharmacologically demonstrable:

- Anisocoria: Unequal pupil size, with the affected pupil being larger, especially in bright light.

- Impaired Light Reflex: Reduced or absent direct and consensual pupillary light reflexes in the affected eye.

- Tonic Accommodation: Slow, delayed, and prolonged pupillary constriction upon near fixation, followed by very slow redilation.

- Pilocarpine Supersensitivity: Marked constriction of the affected pupil in response to dilute pilocarpine (0.025% – 0.125%), with minimal or no response in the normal pupil.

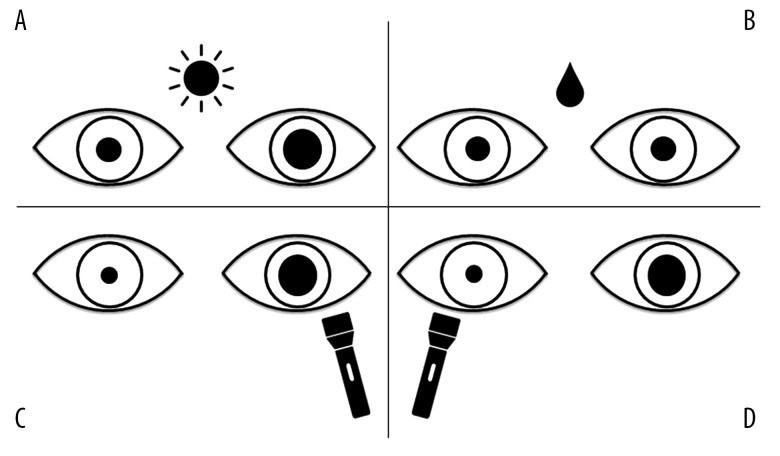

These characteristics are illustrated in Figure 1, which demonstrates the pupillary responses in a patient with Adie’s pupil under different conditions.

Figure 1. Characteristics of Adie’s Pupil

Figure 1: Illustrative features of Adie’s pupil. (A) Under natural light, the left pupil is significantly larger than the right. (B) After applying 0.125% pilocarpine to both eyes, the left pupil shows marked constriction, while the right pupil remains largely unchanged. (C) When a flashlight is shone into the left pupil, it remains unresponsive, whereas the right pupil constricts normally, indicating absent direct light reflex in the left eye and present consensual reflex in the right. (D) Conversely, shining the flashlight into the right pupil causes normal constriction, but the left pupil remains unchanged, demonstrating present direct reflex in the right eye and absent consensual reflex in the left.

Diagnostic Process for Adie’s Pupil

Adie’s pupil diagnosis relies primarily on clinical examination and pharmacological testing. The diagnostic process typically involves:

-

Detailed History: Gathering information about symptom onset, duration, associated symptoms (blurred vision, photophobia, pain), and past medical history, including any neurological symptoms or systemic diseases.

-

Pupillary Examination:

- Observation in Light and Dark: Assess for anisocoria in both bright and dim lighting. Adie’s pupil anisocoria is often more pronounced in bright light because the normal pupil constricts appropriately, while the Adie’s pupil does not.

- Light Reflex Testing: Evaluate direct and consensual pupillary light reflexes using a penlight. Note the speed and extent of constriction and dilation.

- Accommodation Reflex Testing: Observe pupillary constriction when the patient focuses on a near target and redilation when shifting to a distant target. Assess for slowness and tonicity.

-

Pilocarpine Test: This is a crucial pharmacological test for confirming Adie’s pupil diagnosis.

- Procedure: Dilute pilocarpine solution (0.025% to 0.125%) is instilled into both eyes. Pupil size is assessed before instillation and again after 30-60 minutes.

- Interpretation: In Adie’s pupil, the affected pupil will show significant constriction (supersensitivity), often constricting more than the normal pupil. The normal pupil will exhibit minimal or no constriction at these low concentrations. This supersensitivity is due to denervation hypersensitivity of the pupillary sphincter muscle to acetylcholine, the neurotransmitter mimicked by pilocarpine.

-

Neurological Examination: A comprehensive neurological examination should be performed to assess for associated neurological signs, such as diminished deep tendon reflexes, which could indicate Adie syndrome or other neurological conditions.

-

Further Investigations: Depending on clinical findings and suspicion of underlying conditions, further investigations may include:

- Serological Tests for Syphilis: Given the strong association between Adie’s pupil and syphilis, particularly neurosyphilis, serological testing (VDRL, RPR, FTA-ABS) is essential.

- Autoimmune and Inflammatory Markers: If autoimmune conditions are suspected, tests for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), rheumatoid factor (RF), and other relevant markers may be considered.

- Imaging Studies: In cases with atypical presentations or suspected neurological involvement beyond the ciliary ganglion, brain MRI may be indicated to rule out structural lesions or other neurological disorders.

Causes and Pathogenesis of Adie’s Pupil

The exact pathogenesis of Adie’s pupil is not fully understood, but it is generally considered a postganglionic parasympathetic denervation disorder of the ciliary ganglion [3]. The ciliary ganglion, located in the orbit, contains nerve fibers that innervate both the ciliary muscle (responsible for accommodation) and the pupillary sphincter muscle.

The prevailing theory is that Adie’s pupil results from damage to the ciliary ganglion, possibly due to a viral infection or idiopathic factors. This damage leads to neuronal loss in the ganglion. During regeneration, aberrant reinnervation occurs. Because the ciliary ganglion has a much larger population of neurons projecting to the ciliary muscle than to the pupillary sphincter, regenerating fibers intended for the ciliary muscle may misinnervate the pupillary sphincter [40]. This aberrant reinnervation explains the tonic pupillary response and accommodative dysfunction characteristic of Adie’s pupil.

While often idiopathic, Adie’s pupil can be associated with various underlying conditions. A literature review revealed associations with:

- Infectious Diseases: Most notably syphilis, particularly neurosyphilis, is a significant association. Other infections like viral hepatitis, leprosy, AIDS, and COVID-19 have also been reported [7–42].

- Autoimmune Diseases: Conditions like Sjogren’s syndrome, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome, Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), Takayasu arteritis, autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG), and Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS) have been linked to Adie’s pupil.

- Paraneoplastic Syndromes: Certain cancers, such as breast cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, mediastinal small cell carcinoma, and adenoid cystic carcinoma, have been associated with Adie’s pupil as a paraneoplastic manifestation.

- Other Conditions: Migraine, traumatic brain injury, dorsal midbrain syndrome, inferior oblique myectomy (as a surgical complication), and dysautonomia have also been reported in association with Adie’s pupil.

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the disease spectrum associated with Adie’s pupil, based on the literature review.

Figure 2. Disease Spectrum of Adie’s Pupil

Figure 2: The spectrum of diseases associated with Adie’s pupil, as identified in a literature review. This illustrates the diverse range of conditions, from infectious and autoimmune diseases to paraneoplastic syndromes, that clinicians should consider in the differential diagnosis and etiological investigation of Adie’s pupil.

Differential Diagnosis

Accurate Adie’s pupil diagnosis requires differentiating it from other conditions that can cause pupillary abnormalities. Key differential diagnoses include:

- Oculomotor Nerve Palsy (Third Nerve Palsy): This condition also presents with a dilated pupil and impaired light reflex. However, oculomotor nerve palsy typically involves additional signs such as ptosis (drooping eyelid) and restricted eye movements (extraocular muscle weakness). Brain imaging (MRI) can help identify lesions affecting the oculomotor nerve. Pilocarpine testing is usually negative in oculomotor nerve palsy [43, 44].

- Anticholinergic Drug Overdose: Drugs with anticholinergic properties (e.g., atropine) can cause pupillary dilation and loss of light reflex. Anticholinergic overdose presents with systemic symptoms like dry mouth, flushed skin, tachycardia, delirium, and hallucinations [45]. History of medication use or exposure to substances like Datura (a traditional Chinese medicine) should be considered [46].

- Argyll-Robertson Pupil: Typically associated with neurosyphilis, Argyll-Robertson pupils are small (miotic), irregular pupils that do not react to light but do constrict with accommodation (“light-near dissociation”). They are usually bilateral. Unlike Adie’s pupil, Argyll-Robertson pupils dilate poorly with atropine [47].

- Congenital Mydriasis: This is a rare condition characterized by persistent, non-reactive dilated pupils from birth. It is often bilateral and more common in females. A thorough history and negative pilocarpine test can aid in distinguishing it from Adie’s pupil [48].

Treatment and Management

Treatment for Adie’s pupil primarily focuses on managing symptoms and addressing any underlying conditions.

- Pilocarpine Eye Drops: Low-dose pilocarpine (0.1% or 1%) can be prescribed to alleviate symptoms like blurred vision and photophobia by constricting the dilated pupil. However, this is symptomatic treatment and does not address the underlying cause.

- Treatment of Underlying Conditions: If Adie’s pupil diagnosis reveals an associated underlying condition like syphilis, autoimmune disease, or paraneoplastic syndrome, treatment should be directed at the primary disease. In many cases, treating the underlying condition can lead to improvement or resolution of the pupillary abnormalities and ophthalmologic symptoms.

- Observation and Reassurance: For idiopathic Adie’s pupil without significant symptoms, observation and reassurance may be sufficient. Patients should be educated about the benign nature of the condition and advised to seek medical attention if new symptoms develop.

Conclusion

Adie’s pupil diagnosis is based on recognizing its characteristic clinical features: anisocoria, impaired light reflex, tonic accommodation, and pilocarpine supersensitivity. While often idiopathic, clinicians must be vigilant in investigating potential underlying systemic diseases, particularly syphilis and autoimmune disorders. A thorough clinical evaluation, pharmacological testing with dilute pilocarpine, and appropriate investigations are crucial for accurate diagnosis and management. Understanding the differential diagnoses is equally important to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate patient care. By systematically evaluating patients with pupillary abnormalities, clinicians can effectively diagnose Adie’s pupil, address associated conditions, and manage patient symptoms, improving their quality of life.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing of the original article.

Abbreviations

AAG – autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy

AIDS – acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

CIDP – chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy

COVID-19 – coronavirus disease 2019

GBS – Guillain-Barre syndrome

IVIg – intravenous immunoglobulin

IVMP – intravenous methylprednisolone

MFS – Miller Fisher syndrome

VKH syndrome – Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors of the original article declared that they have no competing interests.

Financial support: The original study was supported by grants from the Shanxi Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission (no. 2017033, no. 2020080), Doctoral Fund of the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University (no. YB161706, no. BS03201631), and Shanxi Applied Basic Research Program (no. 201801D221426).

References

[1] Loewenfeld IE. The Pupil: Anatomy, Physiology, and Clinical Applications. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press; 1999.

[2] Kardon R. The Pupil. In: Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL, eds. Liu, Volpe, and Galetta’s Neuro-Ophthalmology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019: 249-320.

[3] Adie WJ. Tonic pupils and absent tendon reflexes: a benign disorder sui generis; its complete and incomplete forms. Brain. 1932;55(1):98-118. [PubMed]

[4] Thompson HS. Adie’s syndrome: some recent observations. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1977;75:587-626. [PubMed]

[5] Holmes G. Partial iridoplegia associated with symptoms of other diseases of the nervous system. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1931;51:209-28.

[6] Ross AT. Progressive selective sudomotor denervation: a case of Adie’s syndrome. Neurology. 1958;8(11):809-17. [PubMed]

[7] Takata T, Ishikawa H, Machida M, et al. A case of Adie’s tonic pupil associated with neurosyphilis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2017;37(2):198-200. [PubMed]

[8] Camoriano GP, Miller NR, Green WR. Adie’s pupil and ophthalmoplegic migraine. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;92(3):402-7. [PubMed]

[9] Jivraj I, Patel CJ, Gandhi RA. Bilateral Adie’s tonic pupils in a patient with neurosyphilis. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr-2018-225905. [PubMed]

[10] Rissardo JP, Caprara AL. Adie’s tonic pupil revealing neurosyphilis in a young man. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2020;176(4):303-4. [PubMed]

[11] Gu Y, Zhang Y, Zhou H, et al. Clinical analysis of 12 cases of Adie’s pupil. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10(11):1779-82. [PubMed]

[12] Pecero-Hormigo I, Rodriguez-Pozo P, Rebolleda G, Munoz-Negrete FJ. Tonic pupil as a presenting sign of neurosyphilis. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2013;88(10):413-15. [PubMed]

[13] Reyes MP, Koss CA, Joshi N. Neurosyphilis presenting as bilateral Adie’s tonic pupils in an HIV-infected man. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(3):243-4. [PubMed]

[14] Cerny R, Bauer P, Stellbrink HJ, et al. Bilateral tonic pupils (Adie syndrome) in HIV infection. Infection. 2011;39(5):471-74. [PubMed]

[15] Ortiz-Seller MC, Garcia-Gonzalez JM, Sanchez-Martinez E, et al. Adie’s tonic pupil associated with COVID-19 infection. J Neuroophthalmol. 2021;41(1):125-28. [PubMed]

[16] Ordás CM, Morales-Cano D, Pérez-García P, et al. Adie’s tonic pupil as a neurological manifestation of COVID-19. Neurologia (Engl Ed). 2021;36(4):317-19. [PubMed]

[17] Karadžić B, Vlajković M, Stefanović I, et al. Adie’s tonic pupil associated with viral hepatitis: two case reports. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2015;143(11-12):711-14. [PubMed]

[18] Lana-Peixoto MA, Andrade GC, Talim SL, et al. Adie’s tonic pupil in leprosy: a case series. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2011;74(5):359-62. [PubMed]

[19] Bhagwan YK, Lam BL, Plant GT. Adie’s tonic pupils in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2010;30(3):277-79. [PubMed]

[20] Miranda JB, Silva LM, Fontes BM, et al. Adie’s tonic pupil as the initial manifestation of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2019;82(4):343-46. [PubMed]

[21] Robles-Cedeño NR, Arevalo JF, Serrano LA, et al. Bilateral Adie’s tonic pupils in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. J Neuroophthalmol. 2012;32(1):58-60. [PubMed]

[22] Narang S, Gupta V, Sharma A, et al. Bilateral Adie’s tonic pupil in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61(10):584-85. [PubMed]

[23] Garza PS, Bhatti MT, Frohman LP. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome presenting with bilateral Adie’s tonic pupils. J Neuroophthalmol. 2010;30(1):49-51. [PubMed]

[24] Sevketoglu E, Incecik F, Herek D, et al. Adie tonic pupil in Guillain-Barre syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2014;29(10):1439-41. [PubMed]

[25] Escorcio-Bezerra ML, dos Santos RM, Sobreira CF, et al. Adie’s tonic pupil in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2012;70(10):811-12. [PubMed]

[26] Matalia J, Bhatti MT. Tonic pupil in Takayasu arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2012;32(3):275-76. [PubMed]

[27] Kaymakamzade K, Demir CF, Serarslan G, et al. Adie’s tonic pupil in Miller Fisher syndrome: two case reports and review of the literature. J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34(4):364-67. [PubMed]

[28] Morimoto S, Kuwabara S. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy presenting with tonic pupil and postural tachycardia. J Neurol Sci. 2010;299(1-2):155-57. [PubMed]

[29] Peyman A, McCulley TJ, Sergott RC, et al. Paraneoplastic Adie’s tonic pupil in a patient with breast cancer. J Neuroophthalmol. 2012;32(4):354-55. [PubMed]

[30] Srinivasan A, Bursztyn D, Katz DM. Bilateral tonic pupils in a child with Hodgkin lymphoma. J Neuroophthalmol. 2011;31(4):348-50. [PubMed]

[31] Horta P, Sa MJ, Moreira I, et al. Tonic pupil as presenting sign of Hodgkin’s lymphoma recurrence. J Neurol. 2013;260(1):293-95. [PubMed]

[32] Zhang X, Zhao L, Zhou D, et al. Paraneoplastic Adie’s tonic pupil associated with mediastinal small cell carcinoma. J Neuroophthalmol. 2015;35(2):178-80. [PubMed]

[33] Yamane T, Arita R, Yoshino K, et al. Adie’s tonic pupil associated with adenoid cystic carcinoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011;55(6):702-4. [PubMed]

[34] Han JY, Kim SH, Choi KD, et al. Adie’s tonic pupil in dorsal midbrain syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2013;33(4):419-21. [PubMed]

[35] Kim KE, Kim US, Lee SY. Adie’s tonic pupil after inferior oblique myectomy in a child. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2015;29(5):343-45. [PubMed]

[36] Babiano-Guerrero S, Arias-Carrión O, Hernandez-Ruiz R, Murillo-Murillo L. Adie’s tonic pupil after traumatic brain injury. J Neuroophthalmol. 2016;36(4):e57-e58. [PubMed]

[37] Tafakhori G, Pilehvarian AA, Elahi B. Pilocarpine for symptomatic relief of Adie’s tonic pupil in migraine. J Headache Pain. 2011;12(5):591-93. [PubMed]

[38] Garrick R, Bird SJ, McCluskey P, et al. Tonic pupils in autonomic neuropathy. Clin Auton Res. 2017;27(6):415-21. [PubMed]

[39] Colak E, Unal F, Mocan MC, et al. Idiopathic Adie’s tonic pupil: clinical characteristics and pupillographic findings. Semin Ophthalmol. 2015;30(5-6):365-70. [PubMed]

[40] Batawi H, Mohamed AO, Elmalik MS. Adie’s tonic pupil: a diagnostic dilemma. Sudan J Paediatr. 2017;17(2):59-62. [PubMed]

[41] Durán-Ferreras E, Pérez-Bartolomé MI, Sánchez-del-Río M, et al. Idiopathic Adie’s tonic pupil in a teenager. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012;49 Online:e65-67. [PubMed]

[42] Rivero Rodríguez F, Álvarez Rivero L, Rodríguez López M, et al. Adie’s tonic pupil: a case report. Arch Soc Can Oftalmol. 2020;31:219-22.

[43] Brazis PW, Lee AG. Clinical Pathways in Neuro-Ophthalmology: An Evidence-Based Approach. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

[44] Wilhelm H. Neuro-ophthalmology. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2012.

[45] Ellenhorn MJ, Barceloux DG. Medical Toxicology: Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Poisoning. New York: Elsevier; 1988.

[46] Bouazza HZ, Guehria A, Kellou N, et al. Datura stramonium poisoning: a case series. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(1):74-75. [PubMed]

[47] Thompson HS, Corbett JJ. Argyll Robertson pupils revisited. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(6):840-45. [PubMed]

[48]доктора J, доктор P, доктор S, et al. Congenital mydriasis: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2014;51 Online:e49-52.