The Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) stands as a pivotal 50-item self-report questionnaire designed to quantify autistic traits in adults and adolescents from the age of 16. Developed by Baron-Cohen and colleagues in 2001, the AQ delves into five distinct subscales, each illuminating specific characteristics pertinent to identifying individuals on the autism spectrum. For professionals in adult autism diagnosis, understanding the AQ and its cut-off scores is crucial for effective assessment.

These subscales are:

- Social Skill: This subscale evaluates an individual’s comfort and confidence in social environments, their inclination towards social activities, and their overall ease in social interactions. It’s not just about sociability, but the qualitative experience of social engagement.

- Attention Switching: This assesses the flexibility of attention, examining the ability to shift focus between tasks and adapt to changes in routines or unexpected situations. Difficulties here can indicate rigidity in thought and behavior, common in autism.

- Attention to Detail: This subscale explores a tendency to focus intensely on details and patterns, sometimes to the point of overlooking the broader context. While detail-orientation can be a strength, in autism, it can be accompanied by challenges in holistic processing.

- Communication: This area investigates the nuances of communication, looking at reciprocal conversation skills, understanding social cues, and interpreting subtleties in social language. Challenges in communication are a core feature of autism.

- Imagination: This subscale assesses imaginative thinking, including the capacity for pretend play, hypothetical reasoning, and engagement with fiction and creative scenarios. While autism is not a deficit of imagination, it often presents differently, sometimes impacting social imagination more than creative pursuits.

The Utility of the AQ in Autism Assessment

The AQ has become a widely accepted tool for measuring autistic traits. Research consistently demonstrates its effectiveness in capturing varying levels of these traits and in distinguishing between autistic and non-autistic individuals. However, it is critical to note that there isn’t a universally agreed-upon optimal cut-off score for definitive diagnosis (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001; Broadbent et al., 2013; Woodbury-Smith et al., 2005). The AQ serves as a valuable component within a comprehensive diagnostic process, rather than a standalone diagnostic instrument.

It is also important to recognize that elevated AQ scores can reflect conditions or traits that co-occur with or are distinct from autism. Therefore, interpretation of AQ results must always be grounded in a thorough understanding of an individual’s developmental history and broader personal profile. For adult autism diagnosis, the AQ is best used as one piece of a larger diagnostic puzzle.

Alt text: Distribution of Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) scores showing ranges for non-autistic individuals and those consistent with autism, highlighting the overlap and variability in autistic traits.

Scoring and Interpreting AQ Results: Cut-Off Considerations

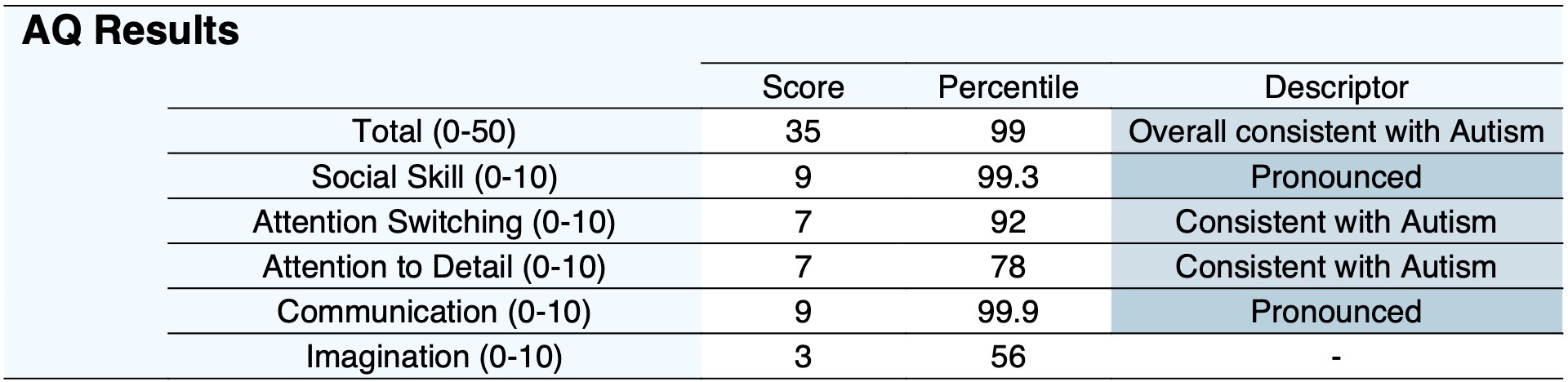

AQ scores are presented in two forms: a total score and individual subscale scores. A higher total score indicates a greater overall presence of autistic traits. Similarly, higher subscale scores point to more pronounced levels of the specific traits associated with each subscale.

Let’s break down what each subscale score represents in more detail based on the item groupings:

- Social Skill Subscale (Items 1, 11, 13, 15, 22, 36, 44, 45, 47, 48): Focuses on difficulties and discomfort in social situations, encompassing challenges in initiating and maintaining social interactions and tendencies to avoid social engagements that are perceived as demanding.

- Attention Switching Subscale (Items 2, 4, 10, 16, 25, 32, 34, 37, 43, 46): Measures difficulties in cognitive flexibility, specifically the ability to shift mental focus between tasks or thoughts, and the level of distress caused by changes to established routines or unexpected disruptions.

- Attention to Detail Subscale (Items 5, 6, 9, 12, 19, 23, 28, 29, 30, 49): Explores the inclination to focus intensely on minute details and patterns within the environment. While this can manifest as meticulousness, it may also present as difficulty in grasping overarching themes or the bigger picture.

- Communication Subscale (Items 7, 17, 18, 26, 27, 31, 33, 35, 38, 39): Assesses challenges in the reciprocity of communication, which includes difficulties in understanding non-verbal cues, interpreting implied meanings, and engaging in the give-and-take of typical conversations.

- Imagination Subscale (Items 3, 8, 14, 20, 21, 24, 40, 41, 42, 50): Examines difficulties related to imaginative thought processes, particularly challenges in engaging with hypothetical scenarios or ‘what if’ situations, which can affect areas like pretend play or understanding abstract concepts.

Percentiles and Thresholds: Contextualizing AQ Scores

Client scores, both total and subscale, are often converted into gender-specific percentiles, benchmarked against normative data from the general adult population (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001; Ruzich et al., 2015). Percentiles provide context, illustrating how an individual’s scores compare to typical scores within the broader population. For instance, a 50th percentile score indicates an average level of autistic traits, while a 90th percentile score places the individual in the top 10%, suggesting a higher level of these traits relative to the general population. Scores in these higher ranges are more frequently observed in autistic adults. Notably, approximately 13% of males and 4% of females in the general population score in ranges that are more typical of autistic individuals on the total AQ.

Cut-Off Scores for “Consistent with Autism” and “Pronounced” Traits

Scores are categorized to reflect their likelihood of aligning with autism. A “Consistent with Autism” classification suggests the score is statistically more similar to scores observed in autistic adults than in the general population. These thresholds are derived from the midpoint between score distributions of autistic and non-clinical samples (Jacobson & Truax, 1991), providing a balanced measure for adult autism diagnosis cut-off.

A “Pronounced” classification indicates scores in the upper half of the autistic distribution, signifying a higher intensity of autistic traits. These thresholds are set at or above the 50th percentile within autistic adult populations. For the Attention to Detail subscale, a more stringent “Pronounced” threshold, set at the 90th percentile within the autistic sample, is used due to score overlap between autistic and non-clinical groups in this specific area.

Scores falling into either “Consistent with Autism” or “Pronounced” categories suggest that the individual exhibits autistic traits at a level commonly seen in autistic adults. Detailed gender-specific score distributions and classifications are available in NovoPsych’s comprehensive review of the AQ (Baker et al., 2024), offering clinicians deeper insights for adult autism diagnosis.

The specific cut-off thresholds for the total AQ score are:

- Males: A score of 26 or above is considered “Consistent with Autism”; 37 or above is “Pronounced.”

- Females: A score of 27 or above is considered “Consistent with Autism”; 39 or above is “Pronounced.”

- Combined (Males and Females): A score of 26 or above is considered “Consistent with Autism”; 36 or above is “Pronounced.”

Alt text: Gender-specific percentile thresholds for Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) total and subscale scores, showing cut-offs for classifications consistent with autism and pronounced autistic traits in males and females.

Gender Considerations in AQ Interpretation

It’s crucial to acknowledge that many autism measures, including the AQ, were initially developed with a focus on male presentations of autism. This can lead to reduced sensitivity in detecting autism in females. Therefore, when a female respondent’s total AQ score is slightly below the “Consistent with Autism” threshold (e.g., in the 23-26 range), it should be interpreted cautiously. A comprehensive assessment should always integrate AQ scores with other sources of information, especially in females, to ensure accurate adult autism diagnosis.

Graphical representations comparing individual total and subscale scores against normative distributions for both autistic and general populations are invaluable tools in interpretation. These graphs, often shaded to highlight the 25th to 75th percentile ranges, visually contextualize a client’s scores relative to typical autistic trait levels in both groups.

Alt text: Comparative graphs of Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) subscale scores for autistic adults and the general population, illustrating differences in social skills, attention switching, attention to detail, communication, and imagination traits.

Psychometric Robustness of the AQ

The AQ is composed of 50 items, with ten items dedicated to each of the five subscales, each grounded in theoretical dimensions of autism (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001). The items were specifically chosen to reflect the classic “triad of impairments” in autism – social interaction difficulties, communication challenges, and repetitive behaviors – as well as associated “areas of cognitive abnormality” (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001, p. 6).

The initial validation of the AQ was conducted with autistic adults (defined as “adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism”) and adults from the general population (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001). This foundational study established that total AQ scores follow a normal distribution and exhibit strong test-retest reliability. The five subscale scores demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.63 to 0.77.

While Baron-Cohen et al. (2001) initially suggested a total score cut-off of 32 to differentiate between autistic and non-autistic individuals, subsequent research by Woodbury-Smith et al. (2005) and Broadbent et al. (2013) proposed optimized cut-off scores of 26 and 29, respectively. This highlights the ongoing refinement and research into optimal cut-off points for adult autism diagnosis using the AQ.

Research consistently shows that males in the general population tend to score higher on the AQ than females. Conversely, autistic females typically score higher than autistic males (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001; Broadbent et al., 2013; Ruzich et al., 2015). These gender-based score variations underscore the necessity of gender-specific norms and cut-off scores in AQ interpretation. NovoPsych addresses this by providing gender-specific norms and thresholds, informed by existing research, to improve the accuracy and interpretability of AQ scores in adult autism diagnosis, as detailed in their review (Baker et al., 2024).

By converting raw AQ scores into gender-specific percentiles, clinicians gain a more nuanced understanding of the degree to which an individual exhibits autistic traits compared to their gender peers within both the autistic and general populations. This percentile-based approach enhances the clinical utility of the AQ in adult autism diagnosis.

Professional Utility and Access to AQ Assessments

Utilize the Autism Spectrum Quotient in your practice with a NovoPsych account

- Designed for Psychologists & Mental Health Professionals

- Securely Send Assessments to Patients Digitally

- Receive Detailed, Automated Reports

- Access to Over 100+ Validated Psychological Assessments

- Instant, Reliable Psychometric Scoring

- Efficient Symptom Tracking Over Time

- Data-Driven Treatment Planning & Monitoring