Introduction

The term “failure to thrive” (FTT) often conjures images of infants not meeting developmental milestones. However, this non-specific label is also worryingly applied to older adults in emergency rooms and hospitals. When doctors use diagnoses like “failure to thrive,” “failure to cope,” or “acopia” for elderly patients, it often signals a lack of clear medical understanding rather than a definitive condition. This article, based on a rigorous study conducted at a tertiary care teaching hospital, delves into the significant negative impacts of using “failure to thrive” as a diagnosis for adults. We will explore how this label can lead to delays in critical care, misdiagnosis, and ultimately, poorer patient outcomes. For healthcare professionals and anyone concerned with the well-being of older adults, understanding the problems associated with the Adult Failure To Thrive Diagnosis and exploring better alternatives is crucial.

The Problem with ‘Failure to Thrive’ in Adults: A Closer Look

“Failure to thrive,” or FTT, is a term borrowed from pediatrics and, unfortunately, transplanted into geriatric care. In the context of older adults, it becomes a catch-all phrase used when the reasons for a patient’s decline are unclear upon hospital admission. This vague syndrome is often characterized by a collection of non-specific symptoms such as:

- Unexplained weight loss

- Loss of appetite

- Cognitive decline

- Functional decline

- Social withdrawal

- Often complicated by existing medical conditions and mental health factors [1–4]

Despite its widespread use in clinical settings and inclusion in the International Classification of Diseases since 1979 [1], there’s a significant lack of consensus on what “failure to thrive” truly means in adults. This ambiguity is a major part of the problem.

The Rising Tide of Older Adults and Emergency Care Pressures

The number of older adults seeking healthcare is increasing as this demographic grows within the general population [5–7]. Simultaneously, emergency departments (EDs) are facing immense pressure due to long wait times and resource allocation challenges [8, 9]. The healthcare system’s focus on efficiency and rapid patient flow, while important, can sometimes overshadow the need for thorough, patient-centered care [8].

It’s been suggested that labels like “failure to thrive” and “failure to cope” might be used as quick, convenient diagnoses to categorize patients with complex presentations, potentially implying that their issues are primarily social rather than medical [6, 10]. This assumption can be detrimental.

The Power of Labels in Healthcare

Diagnostic labels carry significant weight in healthcare. They can shape perceptions of patients and influence how they are treated [6, 11]. One previous study indicated that acute medical conditions, not just social factors, are often the primary reason for hospital admission for patients labeled with FTT. These patients frequently require extensive medical evaluations and interventions like IV fluids and antibiotics [12].

However, before our featured study, the potential harms of using FTT and similar labels in adult patient care remained unexamined. Our study aimed to fill this critical gap by investigating how these diagnostic labels affect the admission process and overall care delivery in emergency settings. We hypothesized that labeling older adults with “failure to thrive” would lead to delays in necessary medical attention and that many of these patients would ultimately be diagnosed with acute medical conditions.

Study Methods: Examining the Impact of Failure to Thrive Diagnosis

To investigate our hypothesis, we conducted a retrospective matched cohort study at a large tertiary care hospital in Vancouver, BC.

Identifying Participants

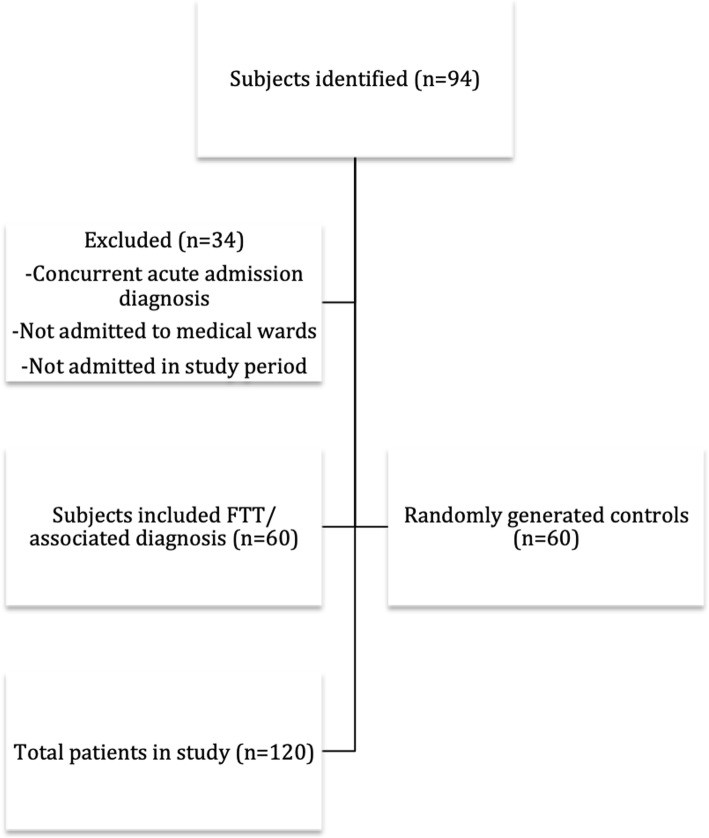

We identified older adults aged 65 years and older who were admitted to acute medical wards between January 1, 2016, and November 1, 2017. The “cases” in our study were patients admitted with a diagnosis of “failure to thrive,” “FTT,” “failure to cope,” or “FTC.” We identified 60 such cases, with a median age of 80 years.

For comparison, we created a control group of 60 age-matched patients (median age 79 years) who met the same inclusion criteria (age ≥65, admitted to acute medical wards) but were admitted with diagnoses other than “failure to thrive” or related terms. This control group allowed us to compare the care pathways and outcomes of patients labeled with FTT to those with more specific admission diagnoses.

Figure 1: Case Selection Process

Alt Text: Flowchart illustrating the patient selection process for a study on failure to thrive diagnosis, detailing inclusion and exclusion criteria for cases and controls.

Ethical Considerations

Our study received ethical approval from the University of British Columbia-Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board. Due to the minimal-risk nature of this retrospective chart review, individual patient consent was waived, in accordance with Canadian ethical guidelines for research.

Data Collection: Measuring Care Delivery

We accessed patient charts through the hospital’s electronic medical record system to collect a range of data points:

- Demographics: Age, gender.

- Diagnoses: Admission and discharge diagnoses.

- In-hospital mortality: To assess patient outcomes.

- Comorbidities: Using the Charlson Comorbidity Index to account for pre-existing health conditions.

- Emergency Department (ED) Timestamps: Crucially, we tracked times from triage, referral to the admitting service, and departure from the ED.

- Physician Assessment Times: Times of assessment by the ED physician and admitting service resident, obtained from discharge summaries and consultation sheets.

- Markers of Acuity: Since vital signs were inconsistently recorded, we used investigations and interventions in the ED as indicators of patient acuity. These included:

- Basic bloodwork (CBC, electrolytes, glucose, creatinine)

- Intravenous antibiotics

- Blood cultures

- Chest X-rays

- Computed Tomography (CT) scans

- Geriatric Care Involvement: We noted if specialized geriatric services (geriatric emergency nurse, geriatric medicine) were consulted.

It’s important to note that while social factors, functional status, and frailty markers are relevant in geriatric care, this information was often poorly documented in the medical records and therefore could not be reliably included in our analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We used standard statistical methods, including averages, medians, and Student’s T-tests, to compare the FTT group and the control group. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Study Results: Delays and Misdiagnosis Linked to Failure to Thrive Label

Our study revealed significant differences in care delivery and diagnostic accuracy between older adults labeled with “failure to thrive” and those with other admission diagnoses.

Patient Demographics: Similar Groups at Baseline

The FTT and control groups were well-matched in terms of demographics and pre-existing health conditions. There were no statistically significant differences in:

- Age distribution

- Gender

- Prevalence of multimorbidity (using Charlson Comorbidity Index)

These similarities at baseline allowed us to confidently attribute any observed differences in outcomes to the admission diagnosis itself, rather than pre-existing patient characteristics.

Table 1: Patient Demographics Comparison

| Demographics | FTT Group (n=60) | Control Group (n=60) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 65–74 | 18 (30%) | 19 (32%) | |

| 75–84 | 25 (42%) | 24 (40%) | |

| 85+ | 17 (28%) | 17 (28%) | |

| Mean ± SD | 80 ± 9.1 | 80 ± 9.0 | 0.38 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 31 (52%) | 28 (47%) | |

| Male | 29 (48%) | 32 (53%) | |

| Multimorbiditya | |||

| 0–5 | 16 (26%) | 20 (33%) | 0.10 |

| 6–10 | 32 (53%) | 32 (53%) | 0.54 |

| > 10 | 12 (20%) | 8 (14%) | 0.09 |

| Mean ± SD | 7.1 ± 1.2 | 6.8 ± 0.9 | 0.13 |

aCalculated using the Charlson Comorbidity Index

Significant Delays in Emergency Department Care

Patients admitted with FTT experienced significantly longer wait times in the ED compared to the control group. The most notable delays occurred in:

- Time to Emergency Room Physician (ERP) Assessment: FTT patients waited significantly longer to be seen by an emergency physician after triage (Table 2).

- Time to Assessment by Admitting Service: Similarly, there was a significant delay in assessment by the admitting medical team for FTT patients.

- Total Time from Triage to Admission: Overall, the total time from triage to hospital admission was considerably longer for the FTT group (10 hours and 40 minutes) compared to controls (6 hours and 58 minutes) – a statistically significant difference (p = 0.001).

Interestingly, while there was a trend toward FTT patients spending more total time in the ED before being transferred to a ward, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Furthermore, a streamlined admission order process designed to expedite admissions was used much less frequently for FTT patients (only 3 times) compared to the control group (16 times), suggesting a slower and potentially more complex admission process for those labeled with FTT. The length of hospital stay was also significantly longer for the FTT group (18.3 days vs. 10.2 days, p = 0.001).

Table 2: Emergency Department and Admission Timelines

| Time Metric | FTT Group (hr:min) | Control Group (hr:min) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Times from: | |||

| Triage to ERP Assessment | 2:00 | 0:49 | 0.02* |

| ERP Referral to Admitting Service | 4:29 | 3:43 | 0.21 |

| Referral to Assessment by Admitting Service | 4:13 | 2:41 | 0.04* |

| Total Times: | |||

| Triage to Admission | 10:40 | 6:58 | 0.001* |

| Triage to Ward | 16:30 | 13:55 | 0.07 |

*Indicates statistical significance

Diagnostic Discrepancies: Failure to Thrive Admission vs. Acute Discharge Diagnoses

One of the most striking findings was the significant discordance between admission and discharge diagnoses in the FTT group. We categorized discharge diagnoses as:

- Acute: Conditions like infections, falls, cardiac issues, drug side effects, renal failure, gastrointestinal bleeds, etc.

- Chronic: Deconditioning, dementia, progressive neurological disorders.

- Mixed: Both acute and chronic conditions.

Remarkably, only 12% (n=7) of patients admitted with FTT were discharged with the same diagnosis. The vast majority, 88% (n=53), received an acute medical diagnosis at discharge. In stark contrast, 95% (n=57) of the control group had concordant admission and discharge diagnoses. Of the few control patients with different discharge diagnoses, some were related to “multifactorial falls” or, notably, “failure to thrive” itself (Table 3). This highlights that while FTT was rarely a final diagnosis, it was overwhelmingly used as an initial label, especially in the FTT group.

Table 3: Admission and Discharge Diagnoses Comparison

| Diagnosis Category | FTT Group (n=60) | Control Group (n=60) |

|---|---|---|

| Chronicity (Discharge) | ||

| Acute | 53 (88%) | 57 (95%) |

| Chronic | 5 (9%) | 2 (3%) |

| Mixed | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) |

| Admission Diagnosis | ||

| FTTa | 60 (100%) | – |

| Infection | – | 22 (36%) |

| Cardiac | – | 11 (18%) |

| GI | – | 6 (20%) |

| Drug-related | – | 2 (3%) |

| Fall | – | 5 (8%) |

| Renal | – | 4 (6%) |

| Neurologic | – | 10 (16%) |

| Discharge Diagnosis | ||

| FTTa | 4 (6%) | 1 (2%) |

| Infection | 21 (35%) | 23 (38%) |

| Cardiac | 14 (23%) | 11 (18%) |

| GI | 5 (8%) | 5 (8%) |

| Drug-related | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) |

| Fall | 7 (12%) | 5 (8%) |

| Renal | 1 (2%) | 3 (5%) |

| Neurologic | 7 (12%) | 10 (16%) |

aAnd related terms: acopia, failure to cope or FTC

Medical Acuity: Similar Investigations, Different Perceptions?

Despite the diagnostic label of “failure to thrive,” the FTT group underwent similar levels of medical investigation and intervention in the ED as the control group. There were no significant differences in:

- Frequency of bloodwork, chest X-rays, or CT scans

- Time to first blood draw or imaging

- Time to administration of intravenous antibiotics

Interestingly, while not statistically significant, twice as many patients in the control group received antibiotics and had blood cultures drawn in the ED compared to the FTT group. This suggests a potential perception bias: patients with specific acute diagnoses on admission might be more readily recognized as medically acute by ED staff, while those labeled with FTT might be initially underestimated in terms of their medical needs, even when presenting with similar levels of objective acuity markers. However, our data did not capture whether FTT patients received these interventions later during their hospital stay.

Table 4: ED Investigations and Interventions

| Metric | FTT Group | Control Group (hr:min) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| hr:min | n (%) | hr:min | |

| Bloodworka | 3:49 | 59 (98%) | 2:10 |

| Antibiotics | 1:19 | 15 (25%) | 1:40 |

| Blood cultures | 1:55 | 25 (42%) | 0:48 |

| Chest X-ray | 1:25 | 47 (78%) | 0:47 |

| CT scans | 2:20 | 34 (57%) | 3:20 |

aBloodwork included basic complete blood count, electrolytes, glucose, and creatinine

Other Outcomes: Geriatric Involvement

In-hospital mortality rates were not significantly different between the groups. However, geriatric specialty involvement was significantly higher in the FTT group (38%) compared to controls (8%). Interestingly, geriatric involvement did not prolong hospital stays in either group, suggesting that while these services were utilized more for FTT patients, it didn’t contribute to their longer length of stay.

Discussion: Failure to Thrive Diagnosis – A Barrier to Timely and Accurate Care

Our study provides compelling evidence that the diagnostic label “failure to thrive,” when applied to older adults in acute care settings, is associated with significant delays in care and diagnostic inaccuracies. Despite often presenting with acute medical conditions, these patients experience slower emergency department processes and longer hospital stays.

Medical Acuity Masked by a Non-Specific Label

The fact that 88% of patients admitted with FTT were ultimately diagnosed with acute medical conditions at discharge strongly suggests that “failure to thrive” is frequently used as an initial label for medically unwell older adults whose underlying conditions are not immediately apparent. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that related terms like “acopia” are rarely final discharge diagnoses [14] and that patients labeled with FTT often have underlying medical issues such as infections, malignancies, and dehydration [3, 12].

Furthermore, the similar frequency of investigations and interventions in the ED between the FTT and control groups indicates that both groups presented with comparable levels of objective medical need. However, the perception of acuity may differ based on the initial diagnostic label. The trend towards fewer antibiotics and blood cultures in the ED for the FTT group, despite similar overall acuity markers, raises concerns about potential biases in initial assessment and treatment decisions.

Delays in Care: A Tangible Harm

Our study is the first to objectively demonstrate delays in care associated with the FTT label. While previous studies have noted the medical complexity of patients labeled with FTT [3, 12, 14], they lacked quantifiable measures of care delays like time to physician assessment and admission. The prolonged ED stays and admission delays we observed for FTT patients are concerning, especially given the known risks of prolonged hospitalization for older adults, including functional decline, loss of independence, increased readmission rates, and higher mortality [3, 16].

Systemic Challenges and Negative Perceptions

Managing older adults in the ED is inherently complex due to atypical disease presentations, polypharmacy, multimorbidity, and communication barriers related to sensory or cognitive impairments [9, 15]. Systemic pressures for efficiency in resource-constrained EDs can exacerbate these challenges. While labeling a patient as “failure to thrive” might seem like a way to streamline the process, our findings indicate the opposite: it leads to longer and potentially more convoluted care pathways.

The term “failure to thrive” itself carries negative connotations. It can imply patient blame and reinforce ageist stereotypes that associate aging with inevitable decline and “aches and pains,” potentially leading to the dismissal of genuine medical complaints [13, 19]. Studies have shown that medical trainees may prefer younger patients with “curable” acute illnesses over older adults with complex, chronic conditions, highlighting potential biases in attitudes towards geriatric care [20, 21].

Moving Towards Better Diagnostic Practices

Older adults presenting with vague symptoms deserve timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment. Our study reinforces the conclusion that “failure to thrive” is a problematic and potentially harmful label that can hinder the search for treatable underlying conditions [13]. Therefore, we strongly advocate for abandoning the use of “failure to thrive” and related terms in clinical practice for older adults.

Instead, we recommend focusing on:

- Symptom-Based Diagnoses: Using the patient’s presenting symptoms as the primary working diagnosis upon admission (e.g., “weakness,” “dyspnea”). These symptoms have established differential diagnoses that guide appropriate investigations.

- Descriptive Terms: When specific medical descriptors are lacking, consider using more neutral and informative terms like “decline in function,” “cognitive decline,” or “frailty.” Importantly, these terms also have ICD codes and are acceptable for medical documentation.

By shifting away from vague and pejorative labels like “failure to thrive,” we can promote more patient-centered, accurate, and timely care for older adults in acute settings.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study, while providing valuable insights, has some limitations:

- Single-Center Study: Conducted at one urban academic hospital, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other settings (e.g., rural hospitals, different healthcare systems).

- Medicine Patients Only: Focused on patients admitted to medical wards, excluding surgical patients.

- Association, Not Causation: The case-control design demonstrates an association between FTT diagnosis and delays in care, but does not prove causation.

Furthermore, we were unable to pinpoint who initially assigned the FTT label and why, due to limitations in documentation. Qualitative research is needed to explore the decision-making processes behind using this term in clinical practice. Ideally, future studies would also incorporate frailty assessments and more comprehensive geriatric evaluations in the initial patient characterization. Longitudinal follow-up data on readmission rates and post-discharge mortality would also provide a more complete picture of the long-term impact of FTT labeling.

Ongoing Research: Understanding the ‘Why’ Behind Failure to Thrive

This study has served as a foundation for ongoing qualitative research involving interviews with healthcare practitioners to understand the reasons for the continued use of “failure to thrive” in our healthcare system. We anticipate that the findings from this qualitative phase will inform targeted educational interventions to reduce the use of this problematic label and promote more appropriate diagnostic approaches for older adults in acute care.

Conclusion: Time to Abandon ‘Failure to Thrive’ for Adult Patients

Our research adds to the growing body of evidence demonstrating that “failure to thrive” is not a helpful or accurate diagnosis for older adults. While previous studies have shown that patients labeled with FTT are often admitted for underlying medical illnesses, our study is the first to demonstrate the detrimental impact of this label on care delivery, specifically causing delays in essential emergency department processes. The use of “failure to thrive” provides minimal clinical value and may, in fact, harm older adults by delaying appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, we reiterate our strong recommendation: it is time to retire “failure to thrive” and associated terms from our clinical vocabulary when caring for older adults. Adopting more specific, symptom-based, and descriptive diagnostic approaches will lead to better care and outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- ED: Emergency department

- FTC: Failure to cope

- FTT: Failure to thrive

- ICD: International Classification of Diseases

Authors’ Contributions

CT: Study design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript. KK: Study concept and design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. MS: Supervising researcher, study concept and design, preparation of manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Approved by the University of British Columbia-Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board (UBC-PHC REB), of the UBC-PHC Research Institute. Individual participant consent was deemed unnecessary by Canadian regulations as laid out in Article 3.7 of the TCPS2 as this study meets requirements defined for minimal risk research.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

- CT, KK: declares that they have no competing interests.

- MS:

- Fellowship grant received from Pfizer in 2015 ($10000)

- Unrestricted research grant received from Pfizer in 2018 ($10000) for urinary incontinence research

- Paid speaking engagements for Pfizer and Astellas on urinary incontinence (2017, 2019)

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Reference 1 (From original article)

- Reference 2 (From original article)

- Reference 3 (From original article)

- Reference 4 (From original article)

- Reference 5 (From original article)

- Reference 6 (From original article)

- Reference 7 (From original article)

- Reference 8 (From original article)

- Reference 9 (From original article)

- Reference 10 (From original article)

- Reference 11 (From original article)

- Reference 12 (From original article)

- Reference 13 (From original article)

- Reference 14 (From original article)

- Reference 15 (From original article)

- Reference 16 (From original article)

- Reference 17 (From original article)

- Reference 18 (From original article)

- Reference 19 (From original article)

- Reference 20 (From original article)

- Reference 21 (From original article)

Associated Data

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.