Introduction: Addressing the Pancreatic Cyst Dilemma

The escalating detection of pancreatic cysts (PCs) through routine abdominal imaging has presented a significant challenge in diagnosis and clinical management. These cysts represent a diverse spectrum of lesions, ranging from benign entities to those with malignant potential. For instance, pseudocysts and serous cystadenomas (SCAs) are generally considered benign and can often be managed with clinical monitoring. Conversely, mucinous pancreatic cysts, such as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) and mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs), carry a risk of progression to invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.1 2 However, the crucial task of differentiating between these cyst types based solely on standard clinical assessments, imaging characteristics, and conventional fluid analysis remains a considerable diagnostic hurdle.3 Furthermore, predicting the progression rate of mucinous PCs to malignancy is complex and often unreliable. Balancing the potential risks of cancer development against the inherent risks associated with surgical intervention has led to the development of both consensus-based and evidence-based guidelines aimed at optimizing the surveillance and treatment strategies for PCs.4 5 While these guidelines represent the best available collective knowledge, numerous studies have highlighted their limitations and imperfections.6–8 Consequently, the clinical approach to managing PCs is frequently individualized and requires refined diagnostic tools.

In recent years, DNA-based testing has emerged as a promising adjunct to the diagnostic armamentarium for pancreatic cyst assessment.9 Although pancreatic cyst fluid (PCF) aspirates obtained via endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) often yield suboptimal cellular content and fluid volumes for traditional ancillary studies like cytopathology and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) quantification, the DNA derived from lysed or exfoliated epithelial cells lining the cyst can be effectively analyzed for genetic abnormalities.10 11 Moreover, advancements in sequencing technologies have revealed distinct mutational profiles associated with different types of PCs, including those that have progressed to invasive adenocarcinoma.12–14 For example, mutations in the KRAS gene are frequently observed in both IPMNs and MCNs, while the presence of GNAS mutations exhibits high specificity for IPMNs.15–17 Conversely, VHL mutations or deletions are characteristic of SCAs, and CTNNB1 mutations, in the absence of other genetic alterations, are commonly found in solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms.13 Crucially, IPMNs exhibiting advanced neoplasia (high-grade dysplasia and invasive adenocarcinoma) have been reported to harbor mutations in TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, and/or AKT1.18–23 Despite the growing body of research evaluating DNA testing for PCs, many studies have been retrospective, utilized postoperative specimens, suffered from limited sample sizes, lacked sufficient follow-up data, and/or employed insensitive detection methods.12 14 24 25 Therefore, the practical diagnostic utility of PCF DNA analysis in routine clinical practice remains to be fully elucidated.

This groundbreaking study addresses this gap by prospectively evaluating DNA-based molecular testing in a large, consecutive cohort of patients undergoing routine PC assessment. We developed a highly sensitive, targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) assay specifically designed to detect genes frequently mutated or deleted in PCs and advanced pancreatic neoplasia, including KRAS, GNAS, NRAS, HRAS, BRAF, CTNNB1, TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT1. While VHL could not be incorporated into this panel due to technical limitations, we assessed its entire coding sequence using Sanger sequencing, acknowledging its lower sensitivity compared to NGS.26 This comprehensive test was implemented within a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified and College of American Pathologists (CAP)-accredited clinical laboratory, utilizing PCF obtained via endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) as part of standard PC evaluation. Our primary objectives were to: (1) prospectively investigate the prevalence and distribution of genetic alterations across different PC types; (2) determine the diagnostic accuracy of molecular analysis using both NGS and Sanger sequencing methodologies; and (3) compare these molecular findings with established diagnostic modalities in the preoperative assessment of PCs, utilizing follow-up diagnostic surgical pathology as the gold standard. This research provides critical insights into the application of advanced health assessment tools for improved clinical diagnosis in primary care settings dealing with pancreatic cysts.

The Significance of DNA-Based Testing in Pancreatic Cyst Evaluation

What We Already Knew: The Foundation of DNA-Based Pancreatic Cyst Assessment

It is well-established that DNA-based testing has become an invaluable adjunct in the diagnostic workup of pancreatic cysts (PCs). Traditional methods for assessing PC fluid, such as cytopathology and CEA quantification, are often hampered by suboptimal cellularity and limited fluid volume in PC aspirates. However, PC fluid inherently contains DNA shed from the epithelial lining of the cyst, offering a unique opportunity for genetic analysis. This DNA, even from lysed or exfoliated cells, can be analyzed to detect genetic abnormalities, providing crucial information for accurate cyst classification and risk stratification.

Prior studies have explored the potential of DNA-based testing in PC diagnosis. These investigations have laid the groundwork for understanding the genetic landscape of various PC types. However, many of these studies were limited by their retrospective design, reliance on postoperative specimens, small sample sizes, inadequate clinical follow-up, and less sensitive detection strategies. These limitations underscored the need for robust, prospective studies to validate the clinical utility of DNA-based PC testing in real-time, preoperative settings.

Groundbreaking Findings: Novel Insights from Prospective NGS Analysis

Our prospective study, conducted on a large cohort of patients, has yielded significant new findings that refine our understanding of DNA-based PC testing. We discovered that mutations in KRAS and/or GNAS, detected through highly sensitive next-generation sequencing (NGS), exhibit exceptional sensitivity and specificity for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). However, it’s important to note that KRAS/GNAS mutations were less sensitive for mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs). This nuanced finding highlights the differential genetic profiles of these mucinous cyst subtypes and emphasizes the need for a comprehensive molecular approach.

A key finding was the superior sensitivity of NGS compared to Sanger sequencing for detecting KRAS and GNAS mutations in preoperative PCF samples. Sanger sequencing, while historically used, demonstrated lower sensitivity in our study, underscoring the advantage of NGS in capturing low-level mutations crucial for accurate diagnosis.

Furthermore, our research uncovered the significant clinical value of detecting mutations or deletions in TP53, PIK3CA, and/or PTEN. The preoperative identification of these alterations, particularly when their mutant allele frequencies (MAFs) are comparable to those of KRAS and/or GNAS mutations, proved to be highly sensitive and specific for IPMNs exhibiting advanced neoplasia, encompassing high-grade dysplasia and invasive adenocarcinoma. This finding is critical for risk stratification and clinical decision-making, allowing for more precise identification of patients requiring aggressive management.

Intriguingly, we also detected low-level mutations in TP53, PIK3CA, and/or PTEN in IPMNs diagnosed with low-grade dysplasia. This observation suggests that these low-level mutations may represent an early warning sign, potentially identifying a subset of IPMNs at increased risk of malignant transformation. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the clinical implications of these findings and their role in long-term surveillance strategies.

Finally, our study revealed a correlation between GNAS mutation allele frequencies and the severity of dysplasia in IPMNs. Specifically, GNAS mutations with MAFs exceeding 55% were significantly correlated with IPMNs exhibiting high-grade dysplasia. This novel observation suggests that GNAS MAF levels could serve as a quantitative biomarker, further refining risk assessment in IPMN management.

Impact on Clinical Practice: Transforming Pancreatic Cyst Management with NGS

Collectively, these findings definitively underscore the transformative potential of preoperative NGS in the accurate classification of pancreatic cysts. NGS-based DNA testing provides clinicians with a powerful tool to distinguish between different cyst types and, crucially, to identify IPMNs harboring advanced neoplasia with high precision. This advanced health assessment capability, integrated into clinical diagnosis in primary care and specialized settings, promises to optimize patient management strategies, potentially leading to earlier interventions for high-risk lesions and more tailored surveillance for lower-risk cysts. The enhanced sensitivity and specificity of NGS, particularly in detecting mutations associated with advanced neoplasia, can significantly improve the accuracy of preoperative risk stratification, informing surgical decisions and ultimately improving patient outcomes in pancreatic cyst management.

Materials and Methods: A Robust Prospective Study Design

This study received ethical approval from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB# PRO13020493). Between January 2014 and July 2017, a total of 673 PCF specimens, obtained via EUS-FNA, were prospectively collected from 642 patients and submitted for molecular testing at the Molecular & Genomic Pathology Laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). The clinical indication for PCF molecular testing in all cases was clinical suspicion of a mucinous PC. Patient demographics, clinical presentation, EUS findings, fluid viscosity (as documented by the endoscopist), CEA analysis, and cytopathological diagnoses were meticulously documented through medical record review. Main duct dilatation on endoscopy was defined as a diameter of ≥5 mm,4 and mural nodules were characterized as uniform echogenic nodules of any size lacking a lucent center or hyperechoic rim.27 A PCF CEA value exceeding 192 ng/mL was considered elevated. Cytopathology specimens were assessed for adequacy using a three-tiered system: satisfactory, less than optimal, and unsatisfactory. Satisfactory specimens contained sufficient epithelial cells and/or mucin representative of the cyst. Less than optimal specimens had scant epithelium without mucin but with at least a few histiocytes. Unsatisfactory specimens were virtually acellular and lacked mucin. Malignant cytopathology was defined as a diagnosis of at least suspicious for adenocarcinoma or positive for adenocarcinoma. Surgical pathology slides were reviewed for all resected specimens, and PC diagnoses were rendered based on established histomorphological criteria.28 Advanced neoplasia was defined as mucinous PCs (IPMN and MCN) with high-grade dysplasia or invasive adenocarcinoma.7 Pathological staging was performed according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Cancer Staging Manual (eighth edition).29

Molecular Testing Methodology: NGS and Sanger Sequencing

Molecular testing was performed prospectively as part of routine clinical care, with a turnaround time of 14 days (mean, 10 days) within the CLIA-certified and CAP-accredited Molecular and Genomic Pathology Laboratory at UPMC. Genomic DNA was extracted from EUS-FNA-obtained PCF using the MagNA Pure LC Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Roche). DNA quantification was performed using the Qubit V.2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Amplification-based targeted NGS (PancreaSeq) was employed, utilizing primers targeting genomic regions of interest, including KRAS, GNAS, NRAS, HRAS, BRAF, CTNNB1, TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT1, with primer sequences and performance characteristics detailed in prior publications.12 30 Amplicons were barcoded, purified, and ligated with specific adapters. DNA quality and quantity were assessed using the 2200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies). Template preparation and enrichment were performed using the Ion One Touch 2 and One Touch ES, followed by massively parallel sequencing on an Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine Sequencer or Ion Proton (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s protocols, and analyzed using Torrent Suite Software V.3.4.2. Bioinformatic data analysis details are available in the online supplementary material. The limit of detection for NGS was 5% mutant allele frequency (MAF) at 500× coverage or 3% MAF at 1000× coverage, with a minimum depth of coverage of 500×. MAF was calculated as the percentage of reads of the mutant allele versus the wild-type allele. Copy number assessment was performed as previously described.31

VHL gene sequencing was performed using Sanger sequencing. DNA was amplified with primers flanking VHL exons 1–3, followed by bidirectional Sanger sequencing using the BigDye Terminator Kit on ABI3730 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Mutation detection was performed using Mutation Surveyor V.3.01 (SoftGenetics). The limit of detection for Sanger sequencing was approximately 10%–20% mutant allele frequency.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistical software, V.23 (IBM). Differences in mutational status were assessed using Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated using standard 2×2 contingency tables for cases with confirmed diagnostic pathology. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of <0.05.

Results: Unveiling the Power of Molecular Markers

Prevalence of Genetic Alterations and Clinicopathological Correlations

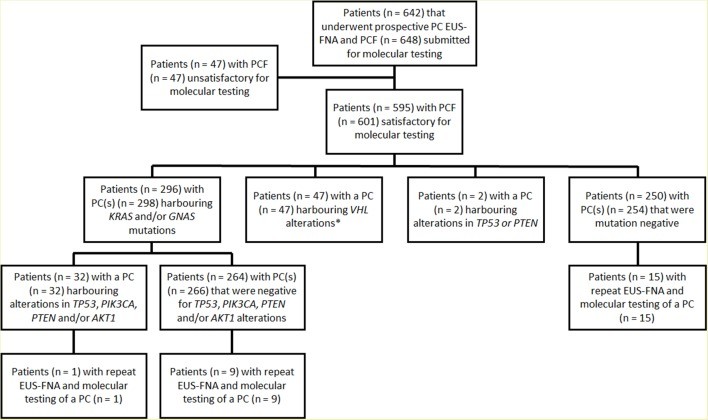

Across a 43-month period, a comprehensive analysis of 673 EUS-FNA-obtained PCF specimens from 642 patients was conducted to identify genetic alterations (Figure 1). Among these, 626 (93%) specimens from 595 patients were deemed satisfactory for molecular testing (Table 1 and online supplementary data). The remaining 47 cases were excluded due to insufficient DNA for analysis. In a small subset of patients, multiple specimens were submitted, including six patients with two separate specimens from distinct PCs and 25 patients who underwent repeat EUS-FNA and molecular testing of the same PC during the study period.

Although sufficient for molecular analyses, cyst fluid volume was insufficient for CEA analysis in 174 of 626 (28%) cases. Furthermore, a significant proportion of specimens, 375 (60%), were classified as either less than optimal (n=297, 47%) or unsatisfactory (n=78, 13%) for cytopathological diagnosis, primarily due to absent to scant cellularity.

DNA concentrations in the submitted PCF specimens ranged widely, from 0.01 to 248 ng/uL (mean, 6.93 ng/uL; median, 4.7 ng/uL). Overall, genetic alterations, utilizing the 11-gene panel, were detected in a substantial proportion of PCs, 357 (57%). NGS revealed activating mutations in key oncogenes: KRAS in 264 (42%), GNAS in 162 (26%), BRAF in 5 (1%), and CTNNB1 in 4 (1%) cases. No mutations were detected in HRAS or NRAS. Notably, combined KRAS and/or GNAS mutations were identified in 308 (49%) PCs, with 119 (19%) cases harboring mutations in both genes (online supplementary table 2). Multiple KRAS mutations were present in 10 specimens, involving various combinations of codon 12, 13, and 61 substitutions. KRAS MAFs ranged from 3% to 55% (mean, 24%; median, 24%). Multiple GNAS mutations were detected in three specimens, involving codon 201 and 227 substitutions, with GNAS MAFs ranging from 3% to 92% (mean, 28%; median, 26%). Two PCs exhibited GNAS MAFs exceeding 55%, specifically 88% and 92%. BRAF and CTNNB1 MAFs ranged from 24% to 46% and 6% to 46%, respectively. BRAF and CTNNB1 mutations were only observed in the presence of KRAS and/or GNAS mutations. Sanger sequencing of VHL exons 1–3 identified VHL mutations and/or deletions in 47 of 626 (8%) PCs throughout the gene coding sequence.

NGS analysis also assessed the status of TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT1 (Table 2). Genetic alterations in these genes were detected in varying frequencies: TP53 in 24 (4%), PIK3CA in 11 (2%), PTEN in 2 (1%), and AKT1 in 1 (1%) PCs. In total, alterations in TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT1 were observed in 35 (6%) cases. For TP53 and PTEN, genetic alterations included mutations and/or deletions across the gene coding sequence, with MAFs ranging from 4% to 43% for TP53, 11% for PTEN, and 8% for AKT1. Homozygous deletions in TP53 and PTEN were detected in 2 (1%) and 1 (1%) cases, respectively. PIK3CA alterations were activating point mutations in exon 9 (n=7) and/or exon 20 (n=5) with MAFs ranging from 3% to 50%.

A significant association was observed between PCs harboring TP53, PIK3CA, and/or PTEN alterations and co-occurring mutations in KRAS and/or GNAS (p<0.001). Notably, only three cases with TP53 mutations (n=2) or PTEN deletion (n=1) were wild-type for both KRAS and GNAS. Among the two TP53 mutant cases, one also harbored a VHL deletion, while the other was negative for other genetic alterations. The single PC with a PTEN deletion also lacked other detected genetic alterations.

Follow-up and Surgical Pathology Correlation: Validating Molecular Findings

Follow-up data were available for the vast majority of patients, 571 of 595 (96%), with a follow-up duration ranging from 1 to 42 months (mean, 27 months; median, 26 months). Diagnostic pathology was obtained for 102 of 595 (17%) patients who underwent surgical resection within 1 to 16 months (mean, 4 months; median, 3 months) following initial EUS-FNA and molecular testing (online supplementary table 2). Surgical indications for most PCs, excluding 2 SCAs, 8 cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs), and 14 pseudocysts, were based on concerns for advanced neoplasia within a mucinous PC, guided by Fukuoka guidelines and molecular testing considerations.7 Preoperative KRAS and/or GNAS mutations were detected in all 56 IPMNs in the surgical cohort. Additionally, KRAS mutations were found in two MCNs with high-grade dysplasia and one MCN with low-grade dysplasia. However, the remaining seven MCNs with low-grade dysplasia were KRAS/GNAS-negative. MAFs for KRAS and GNAS in these surgically resected mucinous cysts ranged from 3% to 47% and 3% to 92%, respectively. The two PCs with MAFs >55% both corresponded to IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia. No KRAS and/or GNAS mutations were detected in non-mucinous PCs within the resection cohort.

Preoperative VHL alterations were identified in two of three SCAs. Although Sanger sequencing failed to detect a VHL alteration in one SCA by EUS-FNA, repeat testing of the surgical resection specimen confirmed a VHL frameshift mutation. No VHL alterations were observed in other mucinous or non-mucinous PCs.

Genetic alterations in TP53, PIK3CA, and/or PTEN were detected in all 13 IPMNs with adenocarcinoma, both IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia, three IPMNs with low-grade dysplasia, and one MCN with low-grade dysplasia (Table 3 and online supplementary table 3). MAFs for these mutations were 8%–43% for TP53, 3%–50% for PIK3CA, and 10% for PTEN. With the exception of the single MCN with low-grade dysplasia, co-mutations in KRAS and/or GNAS were present in all PCs with TP53, PIK3CA, and/or PTEN alterations. Importantly, in the 13 IPMNs with adenocarcinoma and 2 IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia, MAFs for KRAS and/or GNAS were at least equivalent to those of TP53, PIK3CA, and/or PTEN (Figure 2). The three IPMNs with low-grade dysplasia harboring PIK3CA mutations exhibited lower MAFs for PIK3CA compared to KRAS. While no TP53, PIK3CA, or PTEN alterations were found in two IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia, both cases had GNAS MAFs >55%. The remaining MCNs with high-grade dysplasia, IPMNs and MCNs with low-grade dysplasia (excluding those mentioned above), and non-mucinous PCs were negative for TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, and/or AKT1 alterations.

Among the 469 patients with follow-up data but no diagnostic surgical pathology, 230 (49%) had PCs with KRAS and/or GNAS mutations. Of these, 14 (6%) also harbored mutations in TP53, PIK3CA, and/or AKT1. However, MAFs for TP53, PIK3CA, and/or AKT1 (4%–9%) were lower than those for KRAS and/or GNAS (28%–45%). Two additional patients had PCs with TP53 mutations (MAF of 5%) but were wild-type for both KRAS and GNAS. One of these TP53 mutant cases also had a VHL deletion. None of these PCs exhibited concerning features for advanced neoplasia based on imaging (ductal dilatation or mural nodules) or cytopathology (malignant cytology). Importantly, all 16 patients are alive and well without pancreatic cancer development during follow-up.

Repeat EUS-FNA and molecular testing was performed in 25 of 595 patients (Figure 1). Fifteen of these patients had PCs with no detectable alterations, while 10 had KRAS and/or GNAS mutant PCs. Repeat testing consistently confirmed the initial KRAS and GNAS genetic status in all 25 cases. However, in one KRAS and/or GNAS-mutant PC, a TP53 mutation detected in the initial specimen was absent in the subsequent specimen. In this case, initial MAFs for KRAS and TP53 were 39% and 4%, respectively, while the subsequent specimen had a KRAS MAF of only 4%. Comparison of initial and repeat EUS-FNA specimens for the remaining six PCs revealed essentially consistent MAFs for KRAS and/or GNAS.

Comparison of Molecular Testing with Other Diagnostic Modalities

Based on the 102 cases with diagnostic surgical pathology, preoperative NGS detection of KRAS and/or GNAS mutations demonstrated exceptional diagnostic accuracy, with 100% sensitivity and 96% specificity for IPMNs (Table 4). For mucinous PCs overall (IPMNs and MCNs), KRAS and/or GNAS mutations showed 89% sensitivity and 100% specificity. In contrast, traditional markers such as increased fluid viscosity and elevated CEA exhibited lower sensitivities (77% and 57%, respectively) and specificities (89% and 80%, respectively).

The combination of TP53, PIK3CA, and/or PTEN alterations with KRAS and/or GNAS mutations achieved 88% sensitivity and 97% specificity for IPMNs with advanced neoplasia. Sensitivity and specificity both reached 100% when selection criteria were refined to include cases with either GNAS MAFs >55% or TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN MAFs at least equal to KRAS/GNAS MAFs. In comparison, EUS findings of main pancreatic duct dilatation and mural nodules had sensitivities of 47% and 35%, and specificities of 74% and 94%, respectively. Preoperative cytopathological diagnosis of at least suspicious for adenocarcinoma showed 35% sensitivity and 97% specificity.

For mucinous PCs with advanced neoplasia (IPMNs and MCNs), combining KRAS and/or GNAS mutations with TP53, PIK3CA, and/or PTEN alterations yielded 79% sensitivity and 96% specificity. Refining selection criteria to include GNAS MAFs >55% or TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN MAFs equal to or greater than KRAS and/or GNAS MAFs improved diagnostic accuracy to 89% sensitivity and 100% specificity. Cytopathological diagnosis of at least suspicious for adenocarcinoma showed 32% sensitivity and 98% specificity in this context.

Prospective Sanger Sequencing Analysis of KRAS and GNAS: A Comparative Perspective

Prior to this study, prospective EUS-FNA PCF testing for KRAS and GNAS mutations was conducted using Sanger sequencing on 175 PCs from 169 patients over a 12-month period (online supplementary material and supplementary table 3). Among these, 159 (91%) PCs from 153 patients were satisfactory for molecular analysis. Sanger sequencing detected KRAS and/or GNAS mutations in 39% of PCs (62 of 159), lower than the 49% prevalence observed with NGS. In this cohort of 159 PCs, 34 had diagnostic pathology, including 5 IPMNs with adenocarcinoma, 1 IPMN with high-grade dysplasia, 12 IPMNs with low-grade dysplasia, and 2 MCNs with low-grade dysplasia. Sanger sequencing identified KRAS and/or GNAS mutations in 13 of 18 (72%) IPMNs and 0 of 2 (0%) MCNs. Overall, Sanger sequencing for KRAS and/or GNAS mutations showed 72% sensitivity and 100% specificity for IPMNs, and 65% sensitivity and 100% specificity for both IPMNs and MCNs. Among the 159 Sanger-tested PCs, 24 (8 KRAS/GNAS mutant and 16 KRAS/GNAS wild-type) underwent repeat NGS testing for KRAS and GNAS. NGS results largely confirmed Sanger sequencing status; however, NGS identified KRAS (n=3) and/or GNAS (n=1) mutations in 3 of 16 PCs initially classified as KRAS/GNAS wild-type by Sanger sequencing, highlighting the superior sensitivity of NGS.

Discussion: Implications and Future Directions

When evaluating patients with pancreatic cysts, several critical questions arise to guide clinical management. First, accurate cyst type classification is paramount, particularly distinguishing mucinous from non-mucinous cysts due to the malignant potential of the former. Second, it is crucial to determine if a mucinous PC harbors malignancy. Finally, for non-malignant mucinous PCs, assessing their lifetime malignant potential is essential for appropriate surveillance strategies.

Our prospective study, consistent with prior retrospective studies and postsurgical analyses, demonstrates that preoperative DNA-based PC testing, specifically NGS for KRAS and/or GNAS mutations, exhibits high diagnostic accuracy for mucinous PCs, with 89% sensitivity and 100% specificity. Furthermore, KRAS and/or GNAS mutations achieved 100% sensitivity for IPMNs, and GNAS mutations demonstrated 100% specificity for IPMNs. However, KRAS mutations were less frequently detected in MCNs (30%). While KRAS mutations are common in MCNs, their prevalence increases with dysplasia severity.16 17 Jimenez et al reported KRAS mutations in 26% of low-grade and 89% of high-grade MCNs.32 In our study, KRAS mutations were found in 100% of high-grade and 13% of low-grade MCNs. Given the typical recommendation for surgical resection of MCNs due to their malignant potential, especially in younger patients and those with cysts in the pancreatic body and tail, relying solely on KRAS assessment is insufficient for MCN detection, necessitating additional diagnostic markers. Notably, one low-grade MCN in our study harbored a PTEN deletion without a KRAS mutation, suggesting PTEN alterations may serve as potential markers for MCNs. Despite the limited sensitivity for MCNs, DNA testing for mucinous PCs demonstrated superior sensitivity and specificity compared to surrogate markers like fluid viscosity and CEA.

Molecular markers further enhance mucinous PC diagnosis by aiding in differentiation from mimics. Oligocystic and unilocular SCA variants can be clinically and radiographically indistinguishable from branch duct IPMNs and MCNs. VHL genetic alterations are highly specific for SCAs but can also occur in cystic PanNETs.33 In our study, Sanger sequencing for VHL mutations/deletions in SCAs showed 100% specificity. However, preoperative VHL alteration detection failed in one SCA, likely due to Sanger sequencing limitations, as repeat surgical pathology specimen testing revealed a VHL frameshift mutation. This highlights the sensitivity limitations of Sanger sequencing, further underscored by our prospective comparison of Sanger sequencing and NGS for KRAS and GNAS. Sanger sequencing detected KRAS and GNAS mutations in only 39% of PCs, with 72% sensitivity for IPMNs, significantly lower than NGS. This difference is attributable to the lower detection limit of Sanger sequencing (10%–20% mutant alleles) compared to NGS (3%–5% mutant alleles). In our cohort, a substantial proportion of KRAS (24%) and GNAS (22%) mutant cysts had MAFs below the Sanger sequencing detection threshold. Therefore, Sanger sequencing is discouraged for preoperative PCF molecular analysis due to its limited sensitivity.

PC DNA testing is particularly valuable for distinguishing mucinous PCs with low-grade dysplasia from those with advanced neoplasia, based on genetic differences. TP53 and mTOR pathway gene alterations are implicated in mucinous PC malignant transformation. Combining KRAS and/or GNAS mutations with TP53, PIK3CA, and/or PTEN alterations showed 79% sensitivity and 96% specificity for mucinous PCs with advanced neoplasia. Rosenbaum et al reported 46% sensitivity and 100% specificity for advanced neoplasia using preoperative NGS of 113 PCs (38 with diagnostic pathology).25 While they assessed TP53, it was mutated in only 17% of advanced neoplasia cases, compared to 63% in our study. This difference may be due to the significantly higher depth of coverage in our NGS assay (minimum 500×, routinely >1000×) compared to Rosenbaum et al (median 200×).24 25 Deeper coverage enhances assay reliability and sensitivity, crucial for detecting low-frequency mutations.

Analysis of our NGS results revealed two key findings that improve sensitivity and specificity for advanced neoplasia detection. First, GNAS MAF >55% was associated with IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia. KRAS and GNAS mutations are typically heterozygous (MAF ≤50%) due to wild-type allele masking by non-neoplastic cell contamination. Mutant allele-specific imbalance (MASI), where MAF >50% due to wild-type allele loss or mutant allele gain, is a rare phenomenon. KRAS MASI in PCF is reported to correlate with advanced neoplasia.11 Our findings suggest GNAS MASI in PCF, previously undescribed, is also associated with high-grade dysplasia in IPMNs.

Second, TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN MAF at least equal to KRAS/GNAS MAF correlated with advanced neoplasia in IPMNs. While combining KRAS/GNAS mutations with TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN alterations is frequent in advanced neoplasia, KRAS/GNAS and PIK3CA mutations were also found in two low-grade IPMNs. Furthermore, 10 PCs without surgical pathology, harboring KRAS/GNAS and TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN mutations but lacking advanced neoplasia features and showing no progression on follow-up, had lower MAFs for TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN than KRAS/GNAS. Refining NGS selection criteria to include GNAS MAF >55% or TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN MAF at least equivalent to KRAS/GNAS MAF improved sensitivity and specificity for advanced neoplasia in mucinous PCs to 89% and 100%, respectively. In comparison, cytopathological diagnosis of at least suspicious for adenocarcinoma had only 32% sensitivity and 98% specificity. Thus, NGS outperforms other modalities in detecting high-grade dysplasia and invasive adenocarcinoma in mucinous PCs.

The presence of TP53, PIK3CA, and/or PTEN alterations in low-grade IPMNs and clinically non-worrisome IPMNs is noteworthy. Traditionally, these mutations were thought to emerge during IPMN progression to high-grade dysplasia and invasive adenocarcinoma.1 However, Yu et al reported TP53 mutations in secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice samples from both invasive adenocarcinoma and a minority of low-grade IPMN patients, with higher mutant TP53 concentrations in invasive adenocarcinoma cases.22 They also described a case with TP53 mutation detection a year before invasive adenocarcinoma diagnosis, without worrisome imaging features. While the natural history of IPMNs with low-level TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN alterations is unclear, they may represent a high-risk subgroup for malignant progression. Given the high prevalence of mucinous PCs in our cohort (49%), particularly IPMNs, a cost-effective PC surveillance strategy is needed. Detecting KRAS and/or GNAS mutations and low-level TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN alterations in PCF may serve as a predictive marker for malignant potential in IPMNs, warranting further investigation.

Study limitations include surgical selection bias due to diagnostic surgical pathology being available for a small proportion of patients. Testing selection bias exists as only PC specimens satisfactory for NGS and Sanger sequencing were analyzed, although the 7% failure rate suggests minimal impact. The relatively short follow-up period limits assessment of the clinical impact of TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN/AKT1 alteration detection. Ongoing long-term patient monitoring is planned. The 11-gene molecular panel, while targeting common PC alterations, omitted RNF43, CDKN2A, and SMAD4. RNF43 alterations may improve MCN detection sensitivity, but their prevalence is 8%–35% in MCNs, limiting potential impact.22 34 CDKN2A and SMAD4 deletions are associated with advanced neoplasia in IPMNs.18 22 25 While these genes may enhance diagnostic accuracy, our refined selection criteria, incorporating MAFs for GNAS and TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN alterations, already achieved 100% sensitivity and specificity for advanced neoplasia in IPMNs. Further studies are needed to define the minimal gene set for optimal PC assessment. Finally, this study does not address optimal integration of DNA-based molecular testing into current PC surveillance protocols. Prior algorithmic approaches for PC management utilizing molecular testing require further validation before clinical implementation.7 In this study, Fukuoka guidelines were applied, considering molecular testing impact based on prior research.7 12–14 16 19–23 25

Conclusion: Advancing Pancreatic Cyst Management Through Molecular Insights

In conclusion, our large prospective study of DNA-based molecular testing of preoperative EUS-FNA-obtained PCF supports the clinical utility of NGS analysis. NGS demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity in classifying PCs, especially IPMNs, and in diagnosing IPMNs with advanced neoplasia. Limitations include MCN assessment using only KRAS and the inadequacy of Sanger sequencing for PC evaluation. Future research should focus on integrating DNA-based molecular testing into existing management guidelines to optimize patient care and improve outcomes in pancreatic cyst management.

References

[References from original article – same as provided]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file 1

gutjnl-2016-313586supp001.pdf (47.4KB, pdf)

Supplementary file 2

gutjnl-2016-313586supp002.pdf (84.4KB, pdf)

Supplementary file 3

gutjnl-2016-313586supp003.pdf (136.2KB, pdf)

Supplementary file 4

gutjnl-2016-313586supp004.pdf (121.5KB, pdf)