Introduction

In emergency medical scenarios, recognizing and diagnosing an altered level of consciousness (ALOC) is paramount. ALOC signifies a state where a patient isn’t fully awake, alert, or responsive to their surroundings, indicating a potential underlying medical emergency. Accurate and timely Aloc Diagnosis is crucial as it guides immediate interventions and further medical management. This article delves into the complexities of ALOC diagnosis, drawing upon a detailed study conducted in a tertiary hospital in Mogadishu, Somalia, to shed light on the epidemiology, risk factors, and diverse causes of this critical condition. Understanding these aspects is essential for healthcare professionals to effectively approach aloc diagnosis and provide optimal patient care.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors of ALOC

The study, conducted at Mogadishu-Somali-Turkey Training and Research Hospital, a prospective observational study, examined the prevalence of ALOC in patients presenting to the emergency department. Out of 6000 patients admitted over a four-month period, 155, or 2.6%, were diagnosed with ALOC, highlighting the significant presence of this condition in emergency settings. Demographically, the study revealed that 60% of ALOC patients were male, and 40% were female, with an average age of 46.7 years. Older age and male sex emerged as notable demographic risk factors.

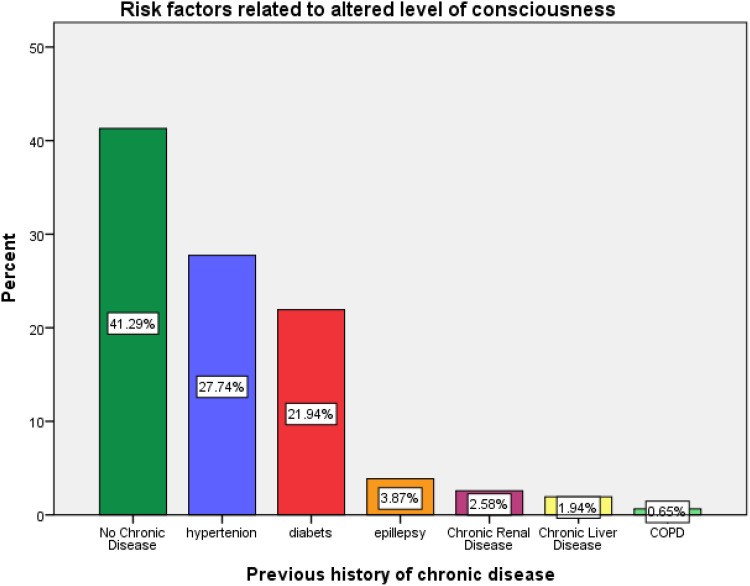

Furthermore, the research identified key pre-existing conditions that significantly elevate the risk of ALOC. Hypertension was the most prevalent risk factor, affecting 27.7% of ALOC patients, followed by diabetes mellitus in 21.9%. Other contributing factors included epilepsy (3.9%) and chronic renal disease (2.6%). These findings underscore the importance of considering a patient’s medical history when approaching aloc diagnosis. The presence of hypertension or diabetes, particularly in older male patients, should raise clinical suspicion for ALOC in emergency scenarios.

Etiology of Altered Levels of Consciousness: Diagnostic Insights

Pinpointing the underlying cause, or etiology, is a critical step in aloc diagnosis. The study meticulously investigated the various etiologies of ALOC in the enrolled patients, categorizing them into non-traumatic (medical) and traumatic causes. Cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), including ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, were the leading non-traumatic causes, accounting for 24.5% of cases. Organ failure and traumatic brain injury (TBI) each contributed to 22% of ALOC cases, emphasizing the broad spectrum of conditions that can manifest as altered consciousness. Infections (12.2%), diabetic emergencies including hypoglycemia (11.6%), shock, and status epilepticus (4% each) also emerged as significant etiologies.

To facilitate accurate aloc diagnosis based on etiology, the study outlined specific diagnostic criteria for common causes of ALOC. For instance, uremic encephalopathy was diagnosed based on a history of renal dialysis, electrolyte abnormalities, and clinical features of chronic renal failure. Stroke diagnosis relied on focal neurological signs and neuroimaging findings (CT or MRI). Sepsis syndrome was identified using established criteria involving infection, systemic inflammation, and organ dysfunction. These detailed diagnostic criteria, summarized in Table 1 of the original study, serve as invaluable tools for clinicians in differentiating between various potential causes of ALOC.

The Role of GCS and Clinical Features in ALOC Diagnosis

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is an indispensable tool in the initial assessment and aloc diagnosis. It provides a standardized and objective measure of consciousness level by evaluating eye-opening, verbal response, and motor response. In this study, the majority of patients (77%) presented with a severely reduced GCS score of 3-8, indicating a deep level of altered consciousness. A smaller proportion (23%) had a moderate reduction in consciousness, with GCS scores of 9-12.

Beyond GCS, clinical features play a vital role in guiding differential aloc diagnosis. The most common presenting features in the study were dyspnea (21.9%), injuries (20%), hemiplegia (16.8%), and convulsions (16.8%). These clinical presentations, in conjunction with GCS assessment, can provide crucial clues to the underlying etiology. For example, hemiplegia strongly suggests a neurological event like stroke, while injuries point towards traumatic causes of ALOC. Table 2 from the original study details the distribution of clinical features alongside other variables, offering a comprehensive overview of patient presentation in ALOC.

Laboratory and Radiological Investigations for ALOC Diagnosis

Laboratory and radiological investigations are essential components of a comprehensive aloc diagnosis workup. The study employed a range of investigations to confirm suspected etiologies and rule out others. Common laboratory tests included serum blood glucose, arterial blood gases, complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, and serum electrolytes. These tests help identify metabolic disturbances like hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, and organ dysfunction, which are frequent causes of ALOC. Table 3 in the original study presents the average laboratory values observed in the ALOC patients, highlighting common abnormalities such as respiratory alkalosis, elevated creatinine and urea levels, and increased inflammatory markers.

Radiological imaging is equally critical, particularly in differentiating between structural and non-structural causes of ALOC. Computed tomography (CT) of the head was routinely performed to exclude intracranial hemorrhage in patients with neurological findings. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was utilized when CT findings were unremarkable but suspicion for ischemic stroke remained high. Chest X-rays, echocardiograms, and abdominal ultrasounds were also employed as clinically indicated to investigate potential cardiac, pulmonary, or abdominal etiologies of ALOC. The utilization rates of these imaging modalities are detailed in Table 2, reflecting the importance of a multimodal diagnostic approach.

Gender and GCS Correlations in ALOC Etiology: Implications for Diagnosis

The study revealed interesting correlations between gender, GCS scores, and ALOC etiology, further refining our understanding of aloc diagnosis. Certain etiologies showed a statistically significant gender predisposition. Uremic encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, subdural hematoma, status epilepticus, and meningitis were more prevalent in males, while sepsis syndrome, shock, traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage, and hyponatremia were more common in females. Hypoglycemia, hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome (HHS), and decompensated heart failure showed equal distribution between sexes.

Furthermore, the severity of ALOC, as indicated by GCS scores, correlated with specific etiologies. Patients with the most severe ALOC (GCS=3) were more likely to have sepsis syndrome, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, uremic encephalopathy, or hypoglycemia. Conversely, different etiologies were more frequently observed in patients with moderately reduced consciousness (GCS 9-12). These gender and GCS-based etiological distributions, detailed in Table 4, provide valuable insights for clinicians to narrow down the differential aloc diagnosis based on patient demographics and initial presentation.

Conclusion: Key Takeaways for ALOC Diagnosis and Management

This study provides critical insights into the epidemiology, risk factors, and etiology of ALOC in an emergency department setting, significantly enhancing our approach to aloc diagnosis. The findings underscore that male sex, older age, hypertension, diabetes, and trauma are major risk factors for ALOC. The most common underlying causes identified were uremic encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, sepsis syndrome, and subdural hematoma. The Glasgow Coma Scale remains a cornerstone in assessing ALOC severity, and specific clinical features, laboratory findings, and radiological investigations are crucial for accurate etiological diagnosis. Furthermore, gender and GCS score correlations with etiology offer additional diagnostic clues.

While this study contributes significantly to our understanding of aloc diagnosis, it is important to acknowledge its limitations, including its single-center nature and relatively small sample size. Future research should expand upon these findings in larger, multi-center studies to further refine diagnostic and management strategies for altered levels of consciousness in diverse patient populations. Nonetheless, the detailed epidemiological and etiological data presented here provide valuable guidance for healthcare professionals striving to improve aloc diagnosis and ultimately enhance patient outcomes in emergency care.