Myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, is a critical medical emergency. While seemingly distant from the automotive world of “xentrydiagnosis.store,” understanding the complexities of health diagnoses like MI can enhance problem-solving skills and analytical thinking, valuable assets in automotive repair. Myocardial ischemia, the underlying cause of MI, arises from insufficient blood supply to the heart muscle due to blocked arteries. This article delves into the alterations in health diagnosis related to myocardial infarction, providing a detailed overview relevant for a diverse audience, including technically-minded professionals.

Myocardial ischemia occurs when the heart muscle doesn’t receive enough oxygen-rich blood. This imbalance between oxygen supply and demand is frequently triggered by a partial or complete blockage in the coronary arteries, most often due to coronary artery disease. In emergency situations, oxygen deprivation leads to ischemia. If this oxygen imbalance persists, it can result in myocardial infarction, or cardiac muscle death.

While coronary artery disease is the primary culprit, other factors can also lead to MI, including:

- Vasospasm: A sudden constriction or narrowing of a coronary artery, restricting blood flow.

- Blood clots (Thrombus): Obstruction of coronary arteries by blood clots, impeding blood circulation.

- Electrolyte imbalances: Disruptions in electrolyte levels can affect heart function and contribute to MI.

- Trauma to the coronary arteries: Physical injury to these vessels can impair blood flow and trigger MI.

Prolonged oxygen deprivation in the heart often manifests as chest pressure or discomfort, the hallmark symptom of MI. This pain can radiate to the neck, jaw, shoulder, or arm. Medical professionals rely on diagnostic tests, laboratory results, and electrocardiogram (ECG) changes to confirm heart damage.

Alt text: ECG readout displaying ST-segment elevation, a key indicator of STEMI myocardial infarction, highlighting alterations in electrical activity during diagnosis.

STEMI vs. NSTEMI: Variations in Myocardial Infarction Diagnosis

Myocardial infarction presents in different forms, notably STEMI (ST-elevation myocardial infarction) and NSTEMI (non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction), which are differentiated by ECG findings. STEMI is characterized by a distinct ST-segment elevation on the ECG, indicating a complete blockage of a coronary artery. In contrast, NSTEMI does not show this ST-segment elevation. In NSTEMI, the coronary artery is only partially blocked, and the ST segment may be depressed or show other changes, but not the characteristic elevation of STEMI. Despite the absence of ST-segment elevation, patients with NSTEMI still experience heart attack symptoms and require immediate medical attention. These alterations in ECG presentation are crucial for initial diagnosis and treatment strategies.

The Nursing Process in Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Approach to Care

In emergency medical settings, nurses play a pivotal role in the rapid assessment and management of suspected MI. The immediate priority is to differentiate MI from other conditions like angina (chest pain due to temporary ischemia). Myocardial infarction necessitates immediate interventions to minimize cardiac tissue damage.

Upon arrival at the emergency room, patients suspected of acute MI undergo immediate steps to reduce ischemia, alleviate pain, and prevent circulatory collapse and shock. The MONA regimen (morphine, oxygen, nitrates, and aspirin) is frequently initiated in the initial management. Continuous cardiac monitoring is established, and intravenous (IV) access is secured for fluid and medication administration. Further diagnostic tests and procedures, such as cardiac catheterization or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), may be necessary depending on the patient’s condition and diagnostic findings.

Beyond immediate interventions, nurses are crucial in patient education and long-term management. They educate patients on medication adherence, dietary modifications, weight management, and lifestyle changes to mitigate risk factors post-MI. Cardiac rehabilitation programs are often recommended to support ongoing recovery and improve long-term outcomes. This holistic nursing process addresses both the acute and chronic phases of myocardial infarction management.

Nursing Assessment: Identifying Key Indicators of Myocardial Infarction

The nursing assessment is the cornerstone of care, involving a comprehensive collection of physical, psychosocial, emotional, and diagnostic data. This section focuses on subjective and objective data relevant to myocardial infarction diagnosis and management.

Review of Health History: Uncovering Clues to Myocardial Infarction

1. General Symptom Evaluation: Patients experiencing MI may present with a range of general symptoms, including:

- Chest, back, shoulder, or jaw pain: Reflecting the referred pain pathways from the heart.

- Palpitations: Irregular heartbeats indicating electrical disturbances.

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea): Due to reduced cardiac output and pulmonary congestion, occurring both at rest and during exertion.

- Fatigue: Generalized weakness resulting from reduced cardiac function.

- Sweating (diaphoresis): A sympathetic nervous system response to pain and stress.

- Nausea and vomiting: Vagal nerve stimulation in response to pain and ischemia.

- Fainting (syncope) and dizziness: Indicating decreased cerebral perfusion due to reduced cardiac output.

2. Detailed Chest Pain Interview: Characterizing chest pain is crucial in differentiating MI from other conditions. Nurses should explore:

- Chest tightness, squeezing, heaviness, or burning sensations: Descriptors commonly used by MI patients.

- Pain location: Arm, shoulder, or jaw pain radiating from the chest.

- Pain triggers: Occurrence during exertion or at rest, providing clues to the nature of ischemia.

- Pain patterns: Intermittent or persistent pain, duration lasting longer than 20 minutes, pain during physical activity, or triggers like stress and emotions.

3. Risk Factor Identification: Assessing risk factors helps determine an individual’s susceptibility to MI.

Non-modifiable risk factors:

- Gender and Age: Men over 45 and women over 50 or post-menopausal are at higher risk.

- Family history of ischemic heart disease: A first-degree relative with heart disease before age 55 increases MI risk.

- Race/ethnicity: Black individuals have a significantly higher risk of MI compared to non-Black individuals.

Modifiable risk factors:

- Hypertension: Uncontrolled high blood pressure stiffens arteries, reducing blood flow to the heart.

- Hyperlipidemia/hypercholesterolemia: Elevated LDL cholesterol and decreased HDL cholesterol increase MI risk by promoting plaque formation.

- Diabetes or insulin resistance: Both conditions contribute to hardening of arteries and increased blood viscosity.

- Tobacco use: Smoking and secondhand smoke are strongly linked to MI due to vascular damage and increased clot formation.

- Obesity: Increased blood volume and pressure in obese individuals strain the heart.

- Physical inactivity: Lack of exercise contributes to arterial rigidity and poor cardiovascular health.

- Diet: High intake of trans and saturated fats promotes cholesterol buildup and arterial blockage.

- Stress: Extreme stress elevates heart rate and blood pressure, increasing strain on constricted arteries.

- Alcohol use: Heavy alcohol consumption negatively affects lipids, platelets, and heart function, increasing MI risk.

- Lack of sleep: Insufficient sleep leads to prolonged elevated blood pressure, increasing cardiovascular risk.

4. Medication Review: Certain medications can have side effects that increase MI risk by constricting blood vessels or increasing cardiac workload:

- Anthracyclines, antipsychotic drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), type 2 diabetes medications (thiazolidinediones and rosiglitazone).

- Recreational and street drugs: Amphetamines, anabolic steroids, cocaine, and nicotine.

5. Emotional Factors: Anginophobia, the fear of chest pain, can trigger panic attacks mimicking MI symptoms, including tachycardia, tachypnea, hypertension, and diaphoresis. Underlying anxiety disorders may contribute to this condition and require mental health support.

Physical Assessment: Objective Signs of Myocardial Infarction

1. Prioritizing ABCs (Airway, Breathing, Circulation): In suspected MI, immediate stabilization of airway, breathing, and circulation is paramount. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be initiated if there is no pulse.

2. Systemic Assessment Approach: A head-to-toe assessment reveals objective signs of MI:

- Neck: Jugular vein distention, indicating fluid overload and heart failure.

- Central Nervous System (CNS): Anxiety, impending doom, syncope, dizziness, lightheadedness, altered mentation due to reduced cerebral perfusion.

- Cardiovascular: Chest pain, new murmurs or bruits (abnormal heart or artery sounds), arrhythmias, and abnormal blood pressure readings.

- Circulatory: Palpitations, weak or thready pulse reflecting reduced cardiac output.

- Respiratory: Dyspnea at rest or with exertion, indicating pulmonary congestion.

- Gastrointestinal: Nausea and vomiting.

- Musculoskeletal: Neck, arm, back, jaw, and upper extremity pain, fatigue.

- Integumentary: Cyanosis, pallor, and excessive sweating, reflecting poor perfusion.

3. ASCVD Risk Score Calculation: The Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) risk score estimates a patient’s 10-year risk of cardiovascular events, aiding in risk stratification and management. Factors include age, gender, race, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, medications, diabetes status, and smoking history. A lower score indicates lower risk.

Alt text: Screenshot of an ASCVD risk score calculator interface, demonstrating a tool used in health diagnosis to assess myocardial infarction risk based on patient data.

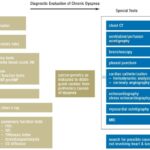

Diagnostic Procedures: Confirming Myocardial Infarction

1. Electrocardiogram (ECG) Interpretation: An ECG within 10 minutes of ER arrival is critical. MI findings on ECG include:

- Pathological Q waves: Q waves greater than 25% of the QRS complex height, indicating myocardial necrosis.

- STEMI: ST-segment elevation.

- NSTEMI: ST-segment depression or other ST-T wave changes, but no ST elevation.

- Both STEMI and NSTEMI: May show T-wave inversions and other abnormalities.

2. Troponin Level Monitoring: Cardiac troponins (troponin I or T) are highly sensitive biomarkers for myocardial damage. Elevated troponin levels confirm myocardial injury. Levels rise 4-9 hours post-damage, peak at 12-24 hours, and remain elevated for 1-2 weeks.

3. Echocardiogram: An echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) is essential for diagnosing acute MI, ideally within 24-48 hours of symptom onset. It assesses heart function, wall motion abnormalities, and ejection fraction. A repeat echo within three months establishes a post-infarction baseline.

4. Advanced Investigations:

- Cardiac CT scan: Accurately identifies coronary artery disease.

- CT coronary angiogram: Uses IV dye to visualize coronary arteries in detail.

Nursing Interventions: Restoring Cardiac Function and Alleviating Symptoms

Nursing interventions are crucial for patient recovery and involve restoring blood flow, relieving pain, and managing symptoms.

Restore Blood Perfusion: Re-establishing Blood Flow to the Heart

1. Reperfusion Therapy: Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and fibrinolytic therapy are vital reperfusion strategies. PCI involves mechanically opening blocked arteries, while fibrinolytic therapy uses medications to dissolve clots. These therapies rapidly restore blood flow to ischemic myocardium, reducing infarct size and improving outcomes.

2. Coronary Revascularization Procedures:

- Coronary angioplasty and stent placement: A balloon catheter is inflated to widen the narrowed artery, and a stent is deployed to maintain artery patency.

- Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery: A new blood vessel is grafted to bypass the blocked coronary artery, creating an alternate route for blood flow.

3. Ischemia Reduction: Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is recommended for PCI patients to prevent stent thrombosis and recurrent events. Anticoagulants like bivalirudin, enoxaparin, and unfractionated heparin are commonly used.

4. Anticoagulant and Antiplatelet Therapy: Blood thinners are crucial in preventing clot formation and reducing MI risk.

- Anticoagulants (e.g., heparin, warfarin) prolong blood clotting time.

- Antiplatelets (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel) prevent platelet aggregation. Aspirin is a cornerstone antiplatelet medication in MI management.

5. Thrombolytic Therapy: Thrombolytics or fibrinolytics (“clot busters”) dissolve existing blood clots, restoring blood flow. Early administration of thrombolytics in MI minimizes heart damage and improves survival.

Relieve Pain: Managing Anginal Pain

1. Pain Management: Intravenous opioids, such as morphine, are frequently used analgesics for MI pain. Morphine reduces myocardial oxygen demand by lowering blood pressure, heart rate, and venous return.

2. Supplemental Oxygen: Oxygen therapy increases oxygen supply to cardiac tissue, reducing ischemic pain and infarct size, and improving cardiac function.

3. Vasodilation Promotion: Nitroglycerin remains a first-line treatment for acute MI. It releases nitric oxide, causing vasodilation and improving myocardial blood flow. It is primarily used for chest pain relief.

Manage Symptoms: Addressing Hemodynamic Instability and Metabolic Disturbances

1. Blood Pressure Management: Antihypertensive therapy aims to achieve target blood pressure goals to prevent complications.

2. Blood Pressure Control Medications:

- Beta-blockers: Reduce myocardial oxygen consumption by decreasing heart rate, blood pressure, and contractility. They are contraindicated in suspected coronary vasospasm.

- ACE inhibitors: Used for patients with systolic left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, hypertension, or diabetes.

- Intravenous nitrates: Effective for symptom relief and ST-segment depression in NSTEMI, often preferred over sublingual nitrates. Dosage is titrated to symptom resolution, blood pressure stabilization, or adverse effect onset (headache, hypotension).

3. Lipid Lowering Therapy: Statins are recommended to lower LDL cholesterol, stabilizing atherosclerotic plaques and preventing vessel occlusion.

4. Blood Glucose Control: Hyperglycemia is common post-MI due to stress-induced hormonal changes. Glucose-lowering treatments are beneficial, regardless of pre-existing diabetes, to normalize blood sugar levels and improve outcomes.

Cardiac Rehabilitation: Enhancing Recovery and Long-Term Health

1. Cardiac Rehabilitation Plan Adherence: Cardiac rehabilitation is essential, particularly post-surgical procedures, reducing mortality after MI or CABG.

2. Complication and Readmission Prevention: Cardiac rehabilitation aids recovery, reducing complication rates and hospital readmissions.

3. Continued Rehabilitation Post-Discharge: Rehabilitation continues at home or in community facilities for approximately three months, tailored to individual needs.

4. Benefits of Cardiac Rehabilitation: Cardiac rehab improves exercise capacity, BMI, lipid profiles, psychological well-being, and overall quality of life post-MI.

Prevent Myocardial Infarction Complications: Promoting Lifestyle Modifications

1. Regular Exercise Promotion: Gradual exercise progression is recommended, starting with 15-20 minutes sessions around 4-6 weeks post-MI, as tolerated and advised by healthcare providers.

2. Healthy Weight Maintenance: Maintaining a healthy weight reduces cardiac workload and blood pressure, decreasing MI risk.

3. Patient Education and Teach-Back: Educating patients on medication regimens, follow-up appointments, and ongoing testing promotes adherence and patient-centered care. “Teach-back” method ensures patient understanding.

4. Stress Management: Stress reduction techniques (yoga, relaxation, guided imagery, deep breathing, meditation) are crucial as stress exacerbates cardiovascular risk.

5. Underlying Condition Management: Controlling diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension is essential to prevent complications and recurrent MI.

6. Lifestyle Modifications: Adopting a heart-healthy lifestyle is key:

- Regular exercise and physical activity.

- Heart-healthy, balanced diet.

- Smoking cessation.

- Stress and anxiety management.

- Limiting alcohol consumption.

7. Regular Follow-up: Recommended follow-up is 3-6 weeks post-discharge for STEMI patients and outpatient follow-up for low-risk NSTEMI and revascularized patients.

8. CPR Training Encouragement: CPR training for caregivers and family members is vital for emergency preparedness.

9. Action Plan for Attack Symptoms: Patients should be educated on recognizing MI symptoms and when to seek immediate medical attention, including nitroglycerin or aspirin use at symptom onset.

10. Addressing Concerns about Sexual Activity: Sexual activity rarely triggers MI and can be resumed when patients feel physically capable.

11. Medical Alert Identification: Medical alert bracelets or IDs inform emergency responders about cardiac history.

Nursing Care Plans: Addressing Common Nursing Diagnoses in Myocardial Infarction

Nursing care plans guide care by prioritizing assessments and interventions for short and long-term goals. Common nursing diagnoses related to MI include:

Acute Pain

Acute pain associated with MI results from chest pain due to inadequate blood flow.

Nursing Diagnosis: Acute Pain

Related to: Blockage of coronary arteries, reduced oxygen supply to the heart.

As evidenced by: Verbal reports of chest pain, pressure, tightness, chest clutching, restlessness, labored breathing, diaphoresis, vital sign changes.

Expected outcomes: Pain relief or control, pain rating reduction, relaxed appearance, ability to sleep and perform daily activities.

Assessment:

- Differentiate angina from MI chest pain based on characteristics (onset, location, duration, relieving factors). MI pain is typically sudden, substernal, radiating, lasting >30 minutes, and unrelieved by rest or nitroglycerin.

- Assess pain characteristics (onset, precipitating factors, relieving measures).

- Obtain ECG during chest pain episodes.

Interventions:

- Administer nitroglycerin sublingually.

- Administer supplemental oxygen.

- Administer morphine intravenously.

- Evaluate pain control measure effectiveness regularly.

Anxiety

Anxiety in MI is triggered by sympathetic nervous system stimulation and the threat of death.

Nursing Diagnosis: Anxiety

Related to: Threat of death, health status, role function changes, lifestyle modifications.

As evidenced by: Increased tension, fearful attitude, apprehension, expressed concerns, restlessness, dyspnea.

Expected outcomes: Verbalization of anxiety cause, understanding of necessary changes, implementation of coping mechanisms, signs of reduced anxiety (stable vital signs, calm demeanor).

Assessment:

- Observe anxiety levels during MI. Anxiety is a common psychological symptom linked to poorer prognosis.

- Examine subjective and objective anxiety cues.

- Assess patient coping mechanisms.

Interventions:

- Acknowledge patient anxieties as valid and encourage verbalization of feelings.

- Provide information and answer questions about tests, procedures, and interventions.

- Involve patients in care planning.

- Implement stress management strategies.

- Teach anxiety reduction techniques (exercise, journaling, breathing, music, medications).

Decreased Cardiac Output

Decreased cardiac output in MI results from loss of viable heart muscle.

Nursing Diagnosis: Decreased Cardiac Output

Related to: Heart rate and electrical conduction changes, reduced preload, reduced blood flow, plaque rupture, occluded artery, altered contractility.

As evidenced by: Chest pain unrelieved by rest/medication, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, anxiety, cool/pale/moist skin, tachycardia, tachypnea, fatigue, dizziness, confusion, dysrhythmias.

Expected outcomes: Maintain blood pressure within acceptable limits, reduced/absent dyspnea/angina/dysrhythmias, understanding of MI and management, participation in activities reducing cardiac workload.

Assessment:

- Identify risk and causative factors for decreased cardiac output (atherosclerosis, clots, heart failure).

- Differentiate angina from MI.

- Closely monitor blood pressure (report SBP < 100 mmHg or 25 mmHg below baseline).

- Obtain ECG.

- Assess for poor cardiac output signs (cool skin, weak pulses, decreased urine output, altered mental status).

- Assess cardiac enzymes (troponin).

Interventions:

- Administer oxygen.

- Administer thrombolytic therapy if indicated, monitor for bleeding.

- Administer beta-blockers.

- Establish IV access.

- Prepare for possible cardiac catheterization.

- Encourage bed rest and activity restrictions.

- Encourage cardiac rehabilitation.

Ineffective Tissue Perfusion

Ineffective tissue perfusion in MI is due to blocked oxygenated blood flow to tissues and organs.

Nursing Diagnosis: Ineffective Tissue Perfusion

Related to: Plaque formation, narrowed/obstructed arteries, plaque rupture, vasospasm, ineffective contraction, compromised blood supply, increased workload.

As evidenced by: Diminished peripheral pulses, increased CVP, tachycardia, dysrhythmias, decreased SpO2, angina, dyspnea, altered LOC, restlessness, fatigue, cold/clammy skin, prolonged capillary refill, pallor, edema, claudication, numbness, pain in lower extremities, poor wound healing.

Expected outcomes: Normal pulses and capillary refill time, warm skin without pallor/cyanosis, alert and coherent LOC.

Assessment:

- Obtain ECG within 10 minutes of admission.

- Assess cardiovascular status, noting signs of ischemia.

- Assess skin color, capillary refill, and pulses.

Interventions:

- Initiate CPR if needed.

- Initiate reperfusion treatment (PCI or fibrinolytics).

- Consider surgical procedures (PCI, CABG).

- Administer aspirin immediately.

- Refer to cardiac rehabilitation.

Risk for Unstable Blood Pressure

Risk for unstable blood pressure in MI is due to blood pressure fluctuations leading to inadequate blood flow.

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Unstable Blood Pressure

Related to: Ineffective heart muscle contraction, ischemia, constricted/obstructed arteries, plaque rupture, coronary artery spasm, underlying cardiac conditions, increased workload.

As evidenced by: (Risk diagnosis – no signs/symptoms, prevention-focused interventions).

Expected outcomes: Maintain blood pressure within normal limits, perform activities without BP fluctuations, medication regimen adherence.

Assessment:

- Monitor blood pressure closely.

- Assess cardiovascular status for complications (arrhythmias, shock, heart failure).

- Assess for signs/symptoms of unstable BP (headache, chest pain, altered mental status, diaphoresis, dizziness).

- Determine risk factors for unstable BP.

- Assess chest pain characteristics and associated sympathetic stimulation.

Interventions:

- Stabilize blood pressure with medications (beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, calcium channel blockers).

- Administer vasodilators as prescribed.

- Relieve fluid overload with diuretics if indicated.

- Provide patient education on blood pressure management and medication adherence.

Understanding myocardial infarction and its diagnostic alterations is crucial for healthcare professionals. For experts in automotive diagnostics at xentrydiagnosis.store, this detailed exploration into medical diagnosis can offer valuable insights into systematic problem-solving, data interpretation, and the critical importance of timely intervention – principles that are equally applicable in the realm of vehicle repair and diagnostics.

References

- American College of Cardiology. (2015, September 21). Is sexual activity safe after MI? Retrieved March 2023, from https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2015/09/21/16/25/is-sexual-activity-safe-after-mi

- Cleveland Clinic. (2021, December 28). NSTEMI: Causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & outlook. Retrieved March 2023, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22233-nstemi-heart-attack#diagnosis-and-tests

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022, October 30). Heart attack: What is it, causes, symptoms & treatment. Retrieved March 2023, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16818-heart-attack-myocardial-infarction#diagnosis-and-tests

- Dewit, S. C., Stromberg, H., & Dallred, C. (2017). Care of Patients With Diabetes and Hypoglycemia. In Medical-surgical nursing: Concepts & practice (3rd ed., pp. 811-817). Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Doenges, M. E., Moorhouse, M. F., & Murr, A. C. (2019). Nurse’s pocket guide: Diagnoses, interventions, and rationales (15th ed.). F A Davis Company.

- Harding, M. M., Kwong, J., Roberts, D., Reinisch, C., & Hagler, D. (2020). Lewis’s medical-surgical nursing – 2-Volume set: Assessment and management of clinical problems (11th ed., pp. 2697-2729). Mosby.

- Hinkle, J. L., & Cheever, K. H. (2018). Management of Patients With Coronary Vascular Disorders. In Brunner and Suddarth’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing (13th ed., pp. 1567-1575). Wolters Kluwer India Pvt.

- Ignatavicius, MS, RN, CNE, ANEF, D. D., Workman, PhD, RN, FAAN, M. L., Rebar, PhD, MBA, RN, COI, C. R., & Heimgartner, MSN, RN, COI, N. M. (2018). Medical-Surgical Nursing: Concepts for Interprofessional Collaborative Care (9th ed., pp. 1386-1388). Elsevier.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Heart attack. Johns Hopkins Medicine, based in Baltimore, Maryland. Retrieved February 2023, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/heart-attack

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, May 21). Heart attack – Symptoms and causes. Retrieved March 2023, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-attack/symptoms-causes/syc-20373106

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2022, August 8). Myocardial infarction – StatPearls – NCBI bookshelf. Retrieved March 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537076/

- Ojha, N., & Dhamoon, A. S. (2022, May 11). Myocardial infarction – StatPearls – NCBI bookshelf. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537076/

- Silvestri, L. A., Silvestri, A. E., & Grimm, J. (2022). Saunders comprehensive review for the NCLEX-RN examination (9th ed.). Elsevier Inc.

- Winchester Hospital. (n.d.). Drugs that may lead to heart damage. Retrieved March 2023, from https://www.winchesterhospital.org/health-library/article?id=31675