Introduction

Arterial aneurysms, characterized by abnormal dilations of arterial walls, pose significant health risks, primarily due to the potential for catastrophic rupture. While atherosclerosis and hypertension are commonly associated with solitary acquired aneurysms, the presence of multiple aneurysms, whether synchronous or appearing over time, necessitates a broader investigation into underlying etiologies. This article delves into the differential diagnosis of multiple arterial aneurysms, considering a range of heritable and non-heritable conditions. We aim to provide clinicians with a robust framework for accurate diagnosis and effective management of patients presenting with this complex vascular pathology.

Case Presentation: Atypical Multiple Aneurysm Development

We present the case of a 51-year-old male patient with a history of statin-managed hyperlipidemia and beta-blocker-controlled atrial fibrillation. Notably, he also had a decade-long history of osteoarthritis but lacked signs of joint hyperelasticity or luxation. His lifestyle included being a non-smoker with a history of social alcohol consumption, and no significant history of infection or cardiomyopathy. His family history was remarkable for aneurysms in both parents, although details regarding location and extent were unavailable, and no family history of cardiomyopathy or connective tissue disease was reported.

The patient’s initial presentation to the emergency department followed a fall, leading to an incidental finding of a 2.9 cm tortuous common iliac artery aneurysm on a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (Figure 1). Bilateral duplication of the renal arteries was also noted (Figure 2). He sustained no fall-related injuries and was discharged post-trauma evaluation.

Figure 1. Left Iliac Artery Aneurysm Progression Over Time

CT angiography images illustrating the left common iliac artery aneurysm (indicated by green arrowheads). (A) Initial presentation showing a 2.9 cm aneurysm. (B, C) Follow-up scans 10 years later, revealing an increase in size to 4.6 cm and marked tortuosity.

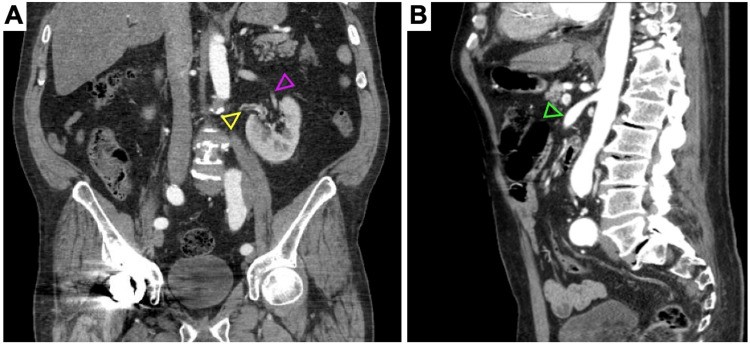

Figure 2. Accessory Renal Arteries and Superior Mesenteric Artery Aneurysm

CT angiograms showing (A) the dominant left renal artery (purple arrowhead), an accessory left renal artery (yellow arrowhead), and (B) a 1.4 cm aneurysm of the proximal superior mesenteric artery (green arrowhead).

Over the subsequent years, additional aneurysms developed. Five years post-initial diagnosis, a 1.7 cm aneurysm of the right common iliac artery was detected via ultrasound (Figure 3). Within the next three years, bilateral femoral artery aneurysms (1.7 cm and 1.9 cm), bilateral popliteal artery aneurysms (1.5 cm and 1.4 cm) (Figure 3), infrarenal aortic ectasia (2.9 cm) (Figure 4), and a superior mesenteric artery aneurysm (1.2 cm) (Figure 2) were identified. Remarkably, previously undetected dilatations of both pulmonary artery roots and intraparenchymal lobar arteriolar ectatic plexuses emerged (Figure 5). Figure 6 provides a timeline of the aneurysm development in this patient.

Figure 3. Bilateral Lower Limb Arterial Aneurysms on Ultrasound

Arterial ultrasound images revealing aneurysms of the (A) right common femoral artery (1.7 cm), (B) left common femoral artery (1.9 cm), (C) right popliteal artery (1.5 cm), and (D) left popliteal artery (1.4 cm).

Figure 4. Abdominal Aorta and Iliac Artery Ultrasound

Ultrasound images showing (A) the left common iliac artery aneurysm, measuring 4.5 cm after 10 years, and (B) fusiform dilatation of the infrarenal abdominal aorta (2.9 cm).

Figure 5. Chest CT Angiogram Revealing Pulmonary Artery Dilatation

(A) Dilatation of the right pulmonary trunk (yellow arrowhead) and (B) intraparenchymal lobar arteriolar ectatic plexus of the right pulmonary vasculature (green arrowhead).

Figure 6. Timeline of Aneurysm Formation

Timeline illustrating the patient’s course of aneurysm development. CTA: Computed tomography angiogram; US: Ultrasound.

Regular monitoring via arterial duplex ultrasound and CT angiograms was implemented for all arterial defects. Over eleven years, the left common iliac artery aneurysm progressed from 2.9 cm to 4.9 cm, necessitating surgical intervention with an interposition arterial graft via a retroperitoneal approach (Figure 1). The remaining aneurysms have remained stable. Currently asymptomatic, the patient is being considered for arteriopathy and connective tissue genetic screening and continues with routine six-month arterial duplex ultrasound surveillance.

Differential Diagnosis of Multiple Systemic Aneurysms

True arterial aneurysms are defined as focal dilatations exceeding 1.5 times the normal vessel diameter, resulting from elastin and collagen degradation within the arterial wall media [2]. They are categorized as saccular, representing focal outpouchings, or fusiform, denoting circumferential widening [2]. Aneurysms in locations such as the common iliac, femoral, popliteal, superior mesenteric, and pulmonary arteries are infrequent [1, 2].

While multiple aneurysms in older patients often correlate with generalized atherosclerosis, the emergence of single or multiple aneurysms in younger individuals, pre-atherosclerotic age groups, strongly suggests the need to explore genetic and connective tissue disorders [1]. The differential diagnosis for multiple systemic aneurysms encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions, including genetic disorders, non-infectious autoimmune vasculitides, mechanical injuries, and infectious etiologies (Table 1).

Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of Multiple Systemic Aneurysms

Source: Reference [1].

| Etiologies | Diagnoses