Ankle osteoarthritis (OA), while less prevalent than hip or knee OA, presents a significant health concern, impacting patient quality of life considerably. Approximately 80% of ankle OA cases stem from post-traumatic events, frequently following malleolar fractures or chronic instability. Affecting individuals around 50 years old on average, ankle OA strikes an active, working-age demographic seeking to maintain mobility and an active lifestyle. This article delves into the critical aspects of Ankle Osteoarthritis Diagnosis, essential for automotive experts who require a comprehensive understanding of conditions that may affect vehicle operation and driver well-being.

Understanding Ankle Osteoarthritis

Ankle osteoarthritis is a chronic condition affecting roughly 1% of the global population, with an estimated incidence of 30 cases per 100,000 individuals, representing 2–4% of all OA patients [1, 2]. Compared to knee and hip OA, ankle OA is significantly less common [1, 2, 3]. Symptomatic knee OA is 8 to 9 times more prevalent, and approximately 24 times more total knee replacements are performed than ankle arthrodesis and arthroplasty combined [3, 4]. Despite being historically underestimated, advanced ankle OA can be profoundly debilitating, with quality of life repercussions comparable to severe hip OA, advanced kidney failure, and congestive heart failure [4, 5].

Unlike hip and knee OA, primary ankle OA is not the most frequent cause [1, 6, 7, 8]. Idiopathic OA accounts for only 7–9% of cases, and 13% are secondary to conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, hemochromatosis, hemophilia, or osteonecrosis. The primary etiology, in 75–80% of cases, is trauma (post-traumatic ankle OA). Fractures in the ankle region (malleolus, distal tibia, talus, etc.) (Fig. 1) are responsible for 62% of these cases, and chronic ligament instability, especially lateral collateral ankle ligament injuries, contributes to another 16% (ligamentous ankle OA) (Fig. 2) [8, 9]. Ankle instability elevates peak joint contact stresses, leading to cartilage deterioration and ultimately OA [9].

Figure 1.

Post-traumatic ankle osteoarthritis twelve years after bimalleolar fracture.

Figure 2.

Varus ankle osteoarthritis resulting from chronic lateral instability of ankle ligaments.

The relationship between osteochondral lesions of the talus and ankle OA development is debated. A 14-year follow-up study by Weigelt et al. [10] suggested that successfully nonoperatively treated osteochondral lesions of the talus have minimal long-term symptoms and low OA progression. Conversely, Stufkens et al. [5] indicated that anterolateral talar, posteromedial tibial, and medial malleolar osteochondral lesions increase the likelihood of ankle OA.

Due to its post-traumatic nature, ankle OA patients are typically younger (18–44 years) than those with other lower limb degenerative joint diseases [2]. They may experience a quicker functional decline, with progression to advanced stages within 10–20 years of onset. Degenerative changes after an ankle fracture can appear within 12–18 months post-injury [7, 11].

Pathophysiology and Cartilage Peculiarities

While the ankle joint is frequently injured, clinically significant ankle OA is less common than in other weight-bearing joints. This may be attributed to unique anatomical, biochemical, and biomolecular characteristics of ankle cartilage [12]. Ankle cartilage endures the highest force per unit area of all human hyaline cartilage (500 N/350 mm2 compared to 500 N per 1100 mm2 or 1120 mm2 in the hip or knee). Load distribution in the ankle also differs, distributing compressive forces over a smaller area. Ankle cartilage (1–1.62 mm) is thinner than knee cartilage (1.69–2.55 mm) [12, 13, 14]. Biologically, ankle cartilage is believed to possess greater self-repair capabilities than knee cartilage [14]. It exhibits higher stiffness and lower permeability due to increased water and proteoglycan content [11]. The denser extracellular matrix enhances load-bearing capacity and reduces susceptibility to mechanical damage [12]. Ankle chondrocytes are also metabolically more active and respond more robustly to anabolic factors like osteogenic protein-1 and C-propeptide of type II collagen, promoting cartilage synthesis. Furthermore, ankle cartilage is less sensitive to catabolic mediators such as fibronectin and interleukin-1 beta, which inhibit collagen synthesis [12, 15]. Synovial fluid in arthritic ankles has demonstrated biochemical alterations, particularly in matrix metalloproteinase concentrations [15], and key markers like aggrecan and BMP-7 increase with OA progression. Conversely, high BMP-2 levels correlate with good clinical function and fewer radiographic OA signs [16].

Despite these protective features, ankle joint cartilage is vulnerable to degeneration when stress and force distribution become asymmetric, such as with joint fractures, impact injuries, or weight-bearing axis malalignment [11, 16]. These factors help explain the strong link between ankle OA and traumatic event history [17].

Clinical Evaluation for Ankle Osteoarthritis Diagnosis

Diagnosis of ankle osteoarthritis hinges on clinical evaluation, focusing on joint pain with mechanical characteristics, potentially accompanied by joint effusion and/or deformity, and reduced mobility, especially ankle dorsiflexion [2, 11]. Scars from prior surgeries (osteosynthesis, hardware removal, cheilectomy, etc.) are common. Other clinical indicators include leg muscle atrophy and gait abnormalities [2, 3].

Imaging plays a crucial role in confirming the clinical diagnosis. Weight-bearing anteroposterior and lateral conventional radiographs (CR), along with a hindfoot alignment view like the Saltzman view, are fundamental [2]. However, CR may underestimate disease severity, particularly in early stages. Advanced three-dimensional (3D) imaging, such as CT and MRI, offers a more precise assessment of cartilage damage extent, location, and size. Newer MRI techniques, like T2 mapping, are being explored for early ankle OA diagnosis, although they are currently more valuable for evaluating repair tissue quality post-surgery [18]. Single-photon emission CT (SPECT-CT) is increasingly used, providing details on OA activity and chondral lesion status alongside anatomical information [19]. Modern SPECT-CT scans enable precise localization of degenerative lesions. SPECT-CT’s sensitivity stems from its ability to detect increased subchondral metabolic osseous activity, which can identify early degenerative changes before clinical symptoms manifest, making it especially useful in early ankle OA diagnosis. It is also valuable for defining OA in multiple joints with varying stages and for inconsistent clinical assessments of pathologies in adjacent structures like talonavicular and subtalar joints [19, 20, 21]. Weight-bearing CT scans have recently emerged, offering enhanced 3D understanding of ankle OA and related supra- and infra-malleolar deformities in a physiological, loaded condition [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27].

Classification Systems for Ankle Osteoarthritis

The Tanaka Classification [28] (Table 1) is a well-recognized system, categorizing ankle OA into four stages. This classification is clinically significant as it sets boundaries for joint-preserving surgery based on joint degeneration grade. However, a 2016 study by Claessen et al. [29] evaluating the Van Dijk, Kellgren–Lawrence, and Tanaka radiological classification systems concluded that none are reliably effective as decision-making tools or for prognosis in post-traumatic ankle OA.

Table 1.

Tanaka classification for ankle osteoarthritis stages based on radiographic findings.

| Stage | Radiographic Finding |

|---|---|

| 1 | No joint space narrowing, early sclerosis and osteophyte formation |

| 2 | Narrowing of the medial joint space |

| 3A | Medial joint space obliteration with subchondral bone contact (medial gutter only) |

| 3B | Obliteration extends to the talar dome roof |

| 4 | Complete joint space obliteration with full bone contact |

Ankle Osteoarthritis Treatment Algorithm

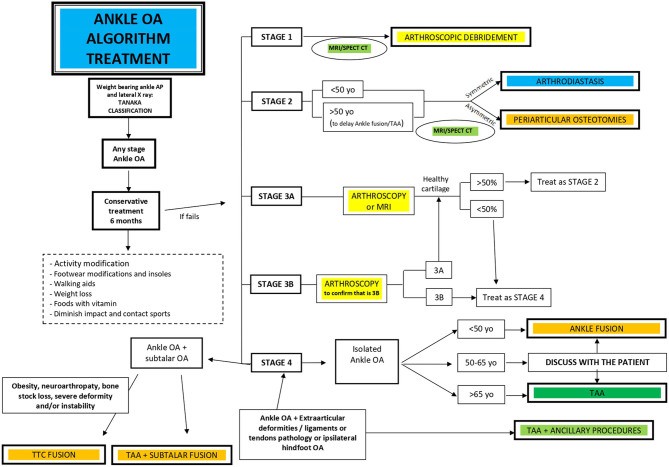

Treatment for ankle osteoarthritis is multifaceted [30] (Fig. 3), encompassing conservative, joint-preserving, and joint-sacrificing surgical procedures. Diagnosis severity dictates the progression through these treatment options.

Figure 3.

Global treatment algorithm for ankle osteoarthritis, guiding decisions from conservative care to surgical interventions.

Initial management always involves conservative treatment, irrespective of OA stage, for at least six months to evaluate effectiveness. Various combined approaches can alleviate ankle OA symptoms, though scientific evidence supporting them is limited, primarily consisting of level IV and V studies [30, 31, 32]. Conservative methods include patient education on modifiable risk factors like obesity, dietary adjustments, physical measures, footwear and orthotic modifications, and pharmacological interventions. Pharmacological treatments range from topical NSAIDs to intra-articular therapies like hyaluronic acid, corticosteroids, and platelet-rich plasma, aimed at pain management and symptom relief.

Surgical interventions are considered when conservative treatments fail. Joint-preserving procedures, such as arthroscopic debridement, joint distraction arthroplasty, and osteotomies around the ankle, are employed in earlier stages of OA. Joint-sacrificing procedures, including total ankle arthroplasty and ankle arthrodesis, are reserved for advanced, end-stage OA.

Conclusion

Accurate and timely diagnosis of ankle osteoarthritis is paramount for effective management and treatment planning. A comprehensive diagnostic approach, incorporating clinical evaluation and advanced imaging techniques like MRI and SPECT-CT, is crucial for determining the stage and severity of OA. While classification systems like Tanaka exist, their reliability for prognosis and treatment decisions is debated. Understanding the nuances of ankle OA diagnosis empowers healthcare professionals and provides a foundation for implementing appropriate conservative or surgical interventions, ultimately aiming to improve patient outcomes and maintain mobility. For automotive experts, recognizing the implications of ankle OA is important as it can directly affect driver comfort and safety.

References

[1] Anderson DD, Amendola A. Osteoarthritis of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005 Jun;87(5):1158-67. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02324. PMID: 15928038.

[2] Valderrabano V, Horisberger M, Russell G, Bajwa S, Verlinden C, Koch P, et al. Etiology of ankle osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009 Jul;467(7):1800-6. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0838-y. Epub 2009 Feb 27. PMID: 19259658; PMCID: PMC2685943.

[3] Lozano-Calderón SA, Souabni A, Park Y, Lee YK, Katz JN, Marx RG, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic hip, knee, and ankle osteoarthritis in the elderly: the MOBILIZE Boston Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Dec;25(12):2009-2015. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.07.018. Epub 2017 Aug 4. PMID: 28780045; PMCID: PMC5701903.

[4] Saltzman CL, Salamon ML, Blanchard GM, Hufford MM, McClellan WT, Brown TD. Foot and ankle osteoarthritis: are commonly used health-related quality-of-life measures responsive and valid? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005 Dec;87(12):2534-41. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01165. PMID: 16334530.

[5] Stufkens SA, Knupp M, ব্যাপার M, Hintermann B, Valderrabano V. Ankle osteoarthritis in young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Jun;91 Suppl 2:151-63. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00048. PMID: 19487549.

[6] Thomas RH, Daniels TR. Ankle arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003 Sep-Oct;11(5):333-43. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200309000-00005. PMID: 14525759.

[7] O’Doherty DP, Indelicato PA, King GJ, Rudicel SA, Shafer BL, Manske PR. Treatment of symptomatic ankle osteoarthritis by arthroscopic debridement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001 Jul;83(7):991-1002. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200107000-00004. PMID: 11451954.

[8] Buckwalter JA, Saltzman CL, Brown TD. The impact of osteoarthritis and cartilage degeneration on joint function. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:3-18. PMID: 11370329.

[9] Hintermann B, Valderrabano V, Tannast M. Ankle joint arthrosis. Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Unfallchirurg. 2003 Oct;106(10):847-57. doi: 10.1007/s00113-003-0634-5. PMID: 14564408.

[10] Weigelt L, Zwicky L, Jaschinski T, Valderrabano V, Hintermann B. Long-term outcome after nonoperative treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2011 May;32(5):439-44. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2011.0439. PMID: 21592334.

[11] Ferkel RD, Chen NC, Sgaglione NA, Del Pizzo W, Parisien JS. Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic anterior impingement of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991 Dec;73(12):1730-44. PMID: 1721428.

[12] Goldring MB, Goldring SR. Articular cartilage biology. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016 Dec 3;18(1):269. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-1170-x. PMID: 27916183; PMCID: PMC5135441.

[13] Mansour JM, Mow VC. The permeability of cartilage under compressive loading. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976 Nov;58(8):1094-104. PMID: 998491.

[14] Klein TJ, Schumacher BL, Burton-Wurster N, Gebbhardt BS, Richmond JC, Herzog W, et al. Anabolic and catabolic responses of canine chondrocytes to compressive loading are source and depth dependent. J Orthop Res. 2003 Jan;21(1):90-9. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00129-9. PMID: 12524320.

[15] Saito T, Fukui N. Matrix metalloproteinases and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009 Jun;17(6):1018-26. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.12.012. Epub 2009 Feb 14. PMID: 19223281.

[16] Lohmander LS, Roos EM. Clinical update: osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2007 Dec 8;370(9601):2056-70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-3. PMID: 18063045.

[17] Saltzman CL, Hill KD, Buckwalter JA. Clinical course of symptomatic ankle osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000 Dec;82(12):1661-8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200012000-00004. PMID: 11135845.

[18] Gold GE, Chen CA, Koo S, Hargreaves BA, Bangerter NK, Del Grande F, et al. Recent advances in MRI of articular cartilage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009 Oct;193(4):638-57. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2833. PMID: 19770230; PMCID: PMC2874443.

[19] Weber M, Baur-Melnyk A, Rombouts J, Rammelt S, Delling G, Bernbeck J, et al. Value of SPECT/CT in suspected osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2012 Oct;33(10):833-40. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0833. PMID: 22990919.

[20] Gorter TM, van den Heijkant EG, Stufkens SA, Kroon HM, Maas M. Diagnostic value of SPECT/CT in patients with chronic ankle pain after trauma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012 Jan;39(1):57-66. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1944-3. Epub 2011 Oct 18. PMID: 22006203; PMCID: PMC3260325.

[21] Hofbauer M, Stuby FM, Zwingmann J, Grifka J, Beckmann J. Single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography of the foot and ankle: a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2018 Oct 18;9(10):202-212. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v9.i10.202. PMID: 30374454; PMCID: PMC6196451.

[22] Hayakawa K, Tanaka Y, Takakura Y, Takaoka T, Hamada M. In vivo three-dimensional analysis of ankle and subtalar joint kinematics during weight bearing using computed tomography. Foot Ankle Int. 2006 Nov;27(11):905-12. doi: 10.1177/107110070602701106. PMID: 17134504.

[23] Knapp JL, Phisitkul P, Anderson DD, Frey CC, Amendola A. Intraoperative weightbearing radiographs to assess tibiotalar joint congruity in total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2011 Feb;32(2):127-33. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2011.0127. PMID: 21349319.

[24] Thawait GK, Carrino JA, Fritz J, Yin Y, Jerecic R, Nanda A, et al. Weight-bearing cone beam CT of the foot and ankle: initial experience. Skeletal Radiol. 2012 Feb;41(2):173-81. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1248-2. Epub 2011 Jul 20. PMID: 21773751; PMCID: PMC3265978.

[25] Kramer PA, Scheffler S, Zacharias V, Woelfle JV, Schmeusser B, Dallaudiere B, et al. Weight-bearing cone beam CT of the foot and ankle: comparison with conventional CT in cadaver specimens. Radiology. 2013 Dec;269(3):813-20. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130041. Epub 2013 Aug 22. PMID: 23963983.

[26] Oehmichen M, Löffler MT, Reising K, Hufeland M, Rupprecht M, Mauch F, et al. Weight-bearing cone-beam CT imaging of the foot and ankle: diagnostic value in comparison to conventional radiography. Rofo. 2014 Jan;186(1):72-8. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1350300. Epub 2013 Oct 17. PMID: 24142463.

[27] Dallaudiere B, Pesquer L, Varenne J, Fantino O, Pham T, Poilvache R, et al. Weight-bearing cone-beam CT of the ankle and hindfoot: normal anatomy, technique, and clinical applications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015 Feb;204(2):W168-77. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12625. PMID: 25611409.

[28] Tanaka Y, Takakura Y, Sugimoto K, Kumai T, Tamai S, Masuhara K. Conservative treatment for osteoarthritis of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006 Dec;88(12):1553-8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B12.18180. PMID: 17151296.

[29] Claessen FM, Doets HC, Tuijthof GJ, Kerkhoffs GM, Blankevoort L, Stufkens SA. Reliability and validity of radiographic classification systems for posttraumatic ankle osteoarthritis. Foot Ankle Int. 2016 Feb;37(2):193-200. doi: 10.1177/1071100715614093. Epub 2015 Nov 18. PMID: 26582955.

[30] Pereira H, Vieira P, Mendes ME, Branco P, Oliveira JM. Ankle Osteoarthritis: Conservative, Surgical, and Biological Treatments. J Clin Med. 2021 Aug 27;10(17):3948. doi: 10.3390/jcm10173948. PMID: 34501353; PMCID: PMC8456144.

[31] Henrotin Y, Lambert C, Mathy-Hartert M, Rozendaal RM, Bruyère O, Reginster JY. Do nutraceuticals have a role in the treatment of osteoarthritis? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011 Apr;25(2):283-95. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2011.03.003. Epub 2011 Apr 9. PMID: 21496874.

[32] Bruyère O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, Branco J, Luisa MC, Radominski SC, et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: a report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014 Dec;44(3):253-63. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.014. Epub 2014 May 27. PMID: 25034994.

[33] Messier SP, Loeser RF, Miller GD, Morgan TM, Rejeski WJ, Sevick MA, et al. Exercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: the Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Dec 15;51(6):883-95. doi: 10.1002/art.20856. PMID: 15595012; PMCID: PMC2771931.

[34] Bliddal H, Christensen R, Christensen P, Bartels EM, Henriksen M, Bennell K, et al. Osteoarthritis, obesity and pain: what are the links? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014 May;26(3):319-24. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000040. PMID: 24667684.

[35] Allen KD, Oddone EZ, LaValley MP, Batlle DD, Golightly YM, Callahan LF. Weight loss and disease activity in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011 May;63(5):711-9. doi: 10.1002/acr.20392. PMID: 21520288; PMCID: PMC3138734.

[36] Veronese N, Koyanagi A, Stubbs B, Cooper C, Reginster JY, Guglielmi G, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with slower progression of osteoarthritis in obese adults. J Bone Miner Res. 2017 Mar;32(3):514-523. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3012. Epub 2016 Nov 14. PMID: 27748063.

[37] Barrea L, Muscogiuri G, Annunziata G, Laudisio D, Pugliese G, Salzano C, et al. Association between Mediterranean diet and disease activity and function in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2019 Jan 28;11(2):238. doi: 10.3390/nu11020238. PMID: 30699846; PMCID: PMC6413178.

[38] Brouwer RW, Jakma TS, Verhagen AP, Verhaar JA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Braces and orthoses for treating osteoarthritis of the knee and hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Apr 18;(2):CD004020. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004020.pub2. PMID: 15846677.

[39] Sasaki T, Ishijima M, Hosaka Y, Sugimoto N, Tanaka M, Saito T. Effect of lateral wedge insole on medial joint space width of osteoarthritic ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2014 Dec;35(12):1264-9. doi: 10.1177/1071100714553275. Epub 2014 Oct 2. PMID: 25278560.

[40] Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, McAlindon TE. Efficacy of topical and transdermal NSAIDs in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019 Feb;48(4):725-732. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.07.011. Epub 2018 Jul 25. PMID: 30122291; PMCID: PMC6348257.

[41] Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Apr;64(4):465-74. doi: 10.1002/acr.21596. PMID: 22477356; PMCID: PMC4715149.

[42] Altman RD, Schemitsch E, Bedi A. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid for osteoarthritis: rationale and clinical applications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015 Nov 4;97(21):1809-17. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00022. PMID: 26538515.

[43] Oe M, Tashiro T, Yoshida H, Matsui Y, Ishiguro N, Tanaka T, et al. Oral hyaluronan relieves knee pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cartilage. 2017 Jan;8(1):25-31. doi: 10.1177/1947603516656114. Epub 2016 Jul 13. PMID: 27412910; PMCID: PMC5206354.

[44] Conaghan PG, Dickson J, Grant RL. Care and management of osteoarthritis in adults: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008 Feb 23;336(7642):502-3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39474.605383.AD. PMID: 18308809; PMCID: PMC2249571.

[45] Mei-Dan O, Carmeli E, Caspi D, Levi N, Stahl S, Norman D, et al. Platelet-rich plasma or hyaluronate for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Am J Sports Med. 2012 Aug;40(8):1734-41. doi: 10.1177/0363546512450107. Epub 2012 Jun 19. PMID: 22711785.

[46] Angthong C, Thinnakote T, Tanpowpong T, Thepparat T, Songcharoen P, Khunsri U, et al. Platelet-rich plasma injections for symptomatic osteochondral lesions of the talus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Foot Ankle Int. 2019 Mar;40(3):261-270. doi: 10.1177/1071100718808990. Epub 2018 Nov 29. PMID: 30486693.

[47] Repetto I, Cavallo C, Bertoni E, Strauss G, Lovati C, Usuelli FG. Platelet-rich plasma injections delay total ankle arthroplasty in osteoarthritic ankles. Cartilage. 2019 Jan;10(1):117-125. doi: 10.1177/1947603517738276. Epub 2017 Oct 26. PMID: 29073831.

[48] Freitag J, Bates D, Boyd R, Shah K, Barnard A, McDonald T, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cartilage. 2016 Jan;7(1):16-31. doi: 10.1177/1947603515608788. Epub 2015 Oct 23. PMID: 26504052; PMCID: PMC4713884.

[49] Boffa A, Colombini A, Morelli F, Perucca Orfei C, Fontana M, Usuelli FG. Intra-articular Injective Treatments for Ankle Osteoarthritis and Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cartilage. 2022 Apr;13(1_suppl):14S-33S. doi: 10.1177/19476035211064409. Epub 2022 Jan 20. PMID: 35050667; PMCID: PMC8859893.

[50] Scranton PE Jr, McDermott JE. Ankle arthroscopy. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994 Oct;25(4):607-21. PMID: 8084212.

[51] van Roermund PM, Marijnissen WJ, Lafeber FP, van der Kraan PM, Welsing PM, Broederick-Villaer Watchman P, et al. Joint distraction in treatment of ankle osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2001 Aug 18;358(9279):376-82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05501-5. PMID: 11513859.

[52] Hintermann B, Valderrabano V. Joint-preserving surgery in ankle osteoarthritis. Foot Ankle Clin. 2007 Dec;12(4):611-25, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2007.08.003. PMID: 18037159.

[53] Knupp M, Ledermann HP, Manoliu SF, Hintermann B. Supramalleolar osteotomies for symptomatic malalignment of the ankle joint: indication, technique, and results. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2012 Oct;24(5):391-406. doi: 10.1007/s00064-012-0171-7. Epub 2012 Oct 10. PMID: 23052745.

[54] Hintermann B, Valderrabano V, Knupp M, Horisberger M, Ledermann HP. Hindfoot realignment and osteotomies for painful varus and valgus malalignment of the ankle and hindfoot. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003 Sep;8(3):491-524. doi: 10.1016/s1083-7543(03)00055-9. PMID: 14518381.

[55] Brodsky JW, Baum BS, Polsky M, Roberts L, FitzPatrick D. Intraarticular tibial osteotomy for ankle arthritis. Foot Ankle Int. 2012 Feb;33(2):113-20. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0113. PMID: 22340904.

[56] Reidsma RJ, Sammarco VJ, Sammarco GJ, Anderson J, Cooper PS. Long-term follow-up after reconstruction of malunited ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2012 Mar;33(3):165-74. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0165. PMID: 22425353.

[57] Valderrabano V, Bradford DS. Total ankle arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Jun;91 Suppl 2:124-34. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00045. PMID: 19487547.

[58] Haddad SL, Coetzee JC, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Gibbons LY, Haims AH, et al. Total ankle arthroplasty versus ankle arthrodesis: systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008 Aug;90(8):2776-84. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00499. PMID: 18670049.

[59] Glazebrook MA, Younger AS, Daniels TR, Thomson CE, Ottawa Ankle Arthroplasty Group. Total ankle arthroplasty: a systematic review. Foot Ankle Int. 2008 Jul;29(7):649-60. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2008.0649. PMID: 18616854.

[60] Gougoulias N, Khanna A, Maffulli N. Total ankle arthroplasty: current concepts and future trends. Br Med Bull. 2009;92:143-57. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldp038. Epub 2009 Oct 14. PMID: 19837717.

[61] Valderrabano V, Kleipool RP, Golano P, Hintermann B, Leumann A. Degenerative joint disease after total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003 Sep;8(3):571-85. doi: 10.1016/s1083-7543(03)00059-6. PMID: 14518385.

[62] Veljkovic A, Glazebrook MA, Amirault D, Sawatzky B, Amirault J, Garwood P, et al. Total ankle arthroplasty versus ankle arthrodesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Foot Ankle Int. 2013 Dec;34(12):1619-28. doi: 10.1177/1071100713504220. Epub 2013 Sep 25. PMID: 24065323.

[63] Thomas RH, Cartwright TW, Gollish JD. Long-term functional outcome following ankle arthrodesis for osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006 Dec;88(12):1559-64. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B12.18225. PMID: 17151297.

[64] Haddad SL, Sommerlath K. Ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003 Sep;8(3):547-59. doi: 10.1016/s1083-7543(03)00057-2. PMID: 14518383.

[65] Spirt AA, Assal M, Hansen ST Jr. Complications of arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2009 Aug;30(8):731-5. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2009.0731. PMID: 19656517.

[66] Moore TJ, Prince JM, Moorman CT 3rd. Tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis with retrograde intramedullary nailing. Foot Ankle Clin. 2002 Mar;7(1):1-14. PMID: 11928683.

[67] Papa JA, Santangelo JR, Nerone VS, Luhmann SJ, Schoenecker PL, Rich MM. Tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis with an intramedullary nail for salvage of complex foot and ankle deformities. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006 Aug;88(8):1757-69. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00947. PMID: 16882855.

[68] Shih FY, Haughom B, Stone J, Crandall JR, Brodsky JW. Total ankle arthroplasty versus ankle arthrodesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective randomized trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Nov 5;96(21):1799-807. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.01281. PMID: 25378534.

[69] Hintermann B, Valderrabano V, Dereymaeker G, Dick W. Conversion of ankle arthrodesis to total ankle arthroplasty: a systematic review. Foot Ankle Int. 2006 Jul;27(7):507-13. doi: 10.1177/107110070602700709. PMID: 16836828.

[70] Valderrabano V, Pagenstert G, Müller I, Götz J, Schiess P, Hintermann B. Ankle arthroplasty versus arthrodesis: a comparative study. Foot Ankle Int. 2006 Jul;27(7):489-500. doi: 10.1177/107110070602700706. PMID: 16836825.

[71] Krause FG, Brodsky JW, Kelly MP, Bohay DR, Maskill JD, Easley ME. Total ankle arthroplasty: major and minor criteria for patient selection. Foot Ankle Int. 2010 May;31(5):429-36. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2010.0429. PMID: 20444454.

[72] Giza E, Kennedy JG. Total talar replacement: a systematic review. Foot Ankle Int. 2015 Apr;36(4):375-81. doi: 10.1177/1071100715570088. Epub 2015 Feb 18. PMID: 25690837.

[73] Saltzman CL, Gougoulias N, Lee MS, Brodsky JW, Younger AS, Daniels TR, et al. Total ankle replacement: systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Jan 1;96(1):68-75. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01593. PMID: 24384897.