Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (AMNs) represent a rare and clinically challenging group of tumors originating in the appendix. Accounting for a small fraction of all cancers, AMNs are characterized by their heterogeneity and the unique management considerations they present to clinicians. This article provides an in-depth review of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms, encompassing their classification, clinical presentation, underlying molecular characteristics, and current treatment strategies. This comprehensive overview aims to serve as a valuable resource for gastroenterologists, pathologists, surgeons, and oncologists involved in the diagnosis and management of this complex disease.

Understanding Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms (AMNs)

Epidemiology and Prevalence of AMN

Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms, while rare, constitute approximately 0.4%–1% of all gastrointestinal malignancies within the United States, translating to roughly 1,500 new diagnoses each year. In contrast to the more common colorectal cancer, AMNs are generally considered to be a more indolent disease, with a lower propensity for developing metastases outside the peritoneal cavity. The age-adjusted incidence of AMN is estimated to be around 0.12 cases per 1 million individuals annually. Notably, the incidence of AMN in the U.S. has shown a significant increase over recent decades, rising from 0.6 cases per million persons in 1973 to 2.8 cases per million persons by 2011, demonstrating an annual percentage increase of 3.1%. Alongside this increase in incidence, the age at diagnosis has also decreased over the same period. Similar trends of increasing incidence and decreasing age at diagnosis have been observed in European populations as well. Demographically, women represent approximately 50%–55% of the appendiceal tumor patient population, and the majority (70%–74%) of patients are of White ethnicity. Peritoneal involvement is the most common presenting stage for patients with AMN, observed in over half of cases.

Clinical Presentation of AMN

Patients with appendiceal tumors often present with non-specific symptoms, which can lead to delays in diagnosis. In the early stages of the disease, the most frequent clinical presentation resembles acute appendicitis, characterized by right lower quadrant pain resulting from the distention of the appendix by mucin. Appendicitis or even appendiceal perforation can occur, particularly if the tumor obstructs the appendiceal orifice. Studies have reported that a significant proportion of patients with appendiceal neoplasms are initially diagnosed with acute appendicitis preoperatively, while a notable percentage are diagnosed incidentally during appendectomy performed for presumed benign conditions.

In advanced stages, AMN typically manifests with an increasing abdominal girth due to the accumulation of mucinous ascites within the peritoneum. Other clinical presentations in advanced disease include chronic abdominal pain, unintentional weight loss, anemia, infertility in women, and the development of new-onset umbilical or inguinal hernias. Despite the common presence of mucinous implants on the peritoneum, serosa, and omentum, intestinal obstruction is an uncommon initial presentation of AMN.

Histopathological Classification of AMN

The classification of appendiceal adenocarcinomas, especially mucinous subtypes, has been a subject of considerable debate and evolution within pathology. The primary categories include mucinous adenocarcinomas, which are the focus of this discussion, and conventional colonic-type adenocarcinomas (non-mucinous), which are histologically similar to those found in the colorectum. A third, increasingly recognized category is appendiceal crypt cell adenocarcinoma (also known as adenocarcinoma ex-goblet-cell-carcinoid), which can also exhibit mucinous features.

The majority of primary appendiceal adenocarcinomas are of the AMN subtype, defined by mucin involvement in more than 50% of the lesion. These neoplasms most commonly originate from low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMNs), which represent adenomatous changes within the appendiceal mucosa. Less frequently, AMNs can arise from polyp-forming adenomas, similar to those seen in the colon, or serrated adenomas. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms exhibiting signet ring cell features or poor differentiation are generally considered more aggressive and associated with a poorer prognosis.

Early classifications of AMN often used terms like appendiceal mucocele, cystadenoma, and cystadenocarcinoma, sometimes considering them benign. However, it is now understood that many of these lesions represent a spectrum of neoplastic potential. Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) refers to the clinical condition characterized by the widespread accumulation of gelatinous mucin in the abdomen and pelvis, along with mucinous implants on peritoneal surfaces. While initially considered a distinct entity, it is now recognized that the majority of PMP cases originate from appendiceal mucinous neoplasms, representing local spread into the peritoneal cavity. Therefore, current recommendations suggest limiting the term PMP to describe the clinical presentation of mucinous ascites rather than using it as a specific histologic diagnosis.

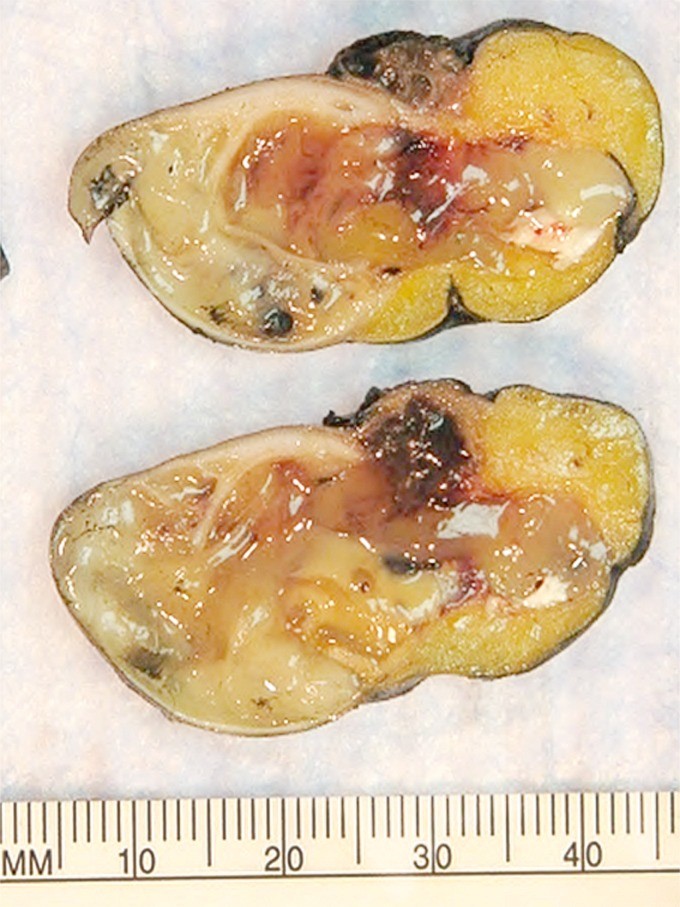

Figure 1. Gross specimen of appendix with mucinous material characteristic of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN), showing protrusion into the mesoappendix.

Figure 2. Microscopic view of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) with invasive low-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma component, highlighting papillary villous epithelium and mucin lakes.

Figure 3. Microscopic image of invasive intestinal type adenocarcinoma of the appendix, contrasting with low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMN).

Figure 4. Microscopic view of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) with paucicellular mucinous spread to peritoneal surfaces, illustrating low-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma.

Figure 5. Microscopic view of high-grade invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma involving peritoneal surfaces, originating from a low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN).

Figure 6. Microscopic image of appendiceal crypt cell adenocarcinoma with mucinous areas, showing goblet-cell carcinoid and signet ring cell patterns, distinguishing it from LAMN.

Several classification systems have been proposed for AMNs, primarily based on cellularity and differentiation. Ronnett and colleagues initially categorized AMNs into three main variants: disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM), peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis (PMCA), and PMCA of indeterminate or discordant features (PMCA I/D). This classification demonstrated prognostic significance, with DPAM associated with a more indolent course and PMCA with a higher metastatic potential and worse outcomes. However, it was later recognized that the intermediate category (PMCA I/D) behaved more similarly to the PMCA group. Consequently, Ronnett’s classification was revised and simplified into a two-tiered system: low-grade and high-grade carcinoma. In this revised classification, any mucinous epithelium extending beyond the muscularis mucosa is considered evidence of invasive appendiceal malignancy. Bradley et al. further refined the classification by grading DPAM and PMCA I/D into well-differentiated (grade 1), moderately differentiated (grade 2), and high-grade (grade 3) mucinous adenocarcinoma. Misdraji et al. introduced the term LAMN to replace “mucocele” and developed a classification system that incorporated localized appendiceal disease in addition to peritoneal involvement. The Ronnett classification, in its simplified low-grade/high-grade form, is currently the most widely accepted internationally.

Diagnostic Approaches for Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasms

Imaging Modalities

While imaging is not definitively diagnostic for AMN, various modalities play a crucial role in detection, staging, and monitoring treatment response. Computed tomography (CT) scans are frequently used and can reveal appendiceal enlargement, cystic masses, and peritoneal disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may provide better soft tissue contrast and can be helpful in characterizing mucinous collections. However, imaging findings are often non-specific, and the diagnosis ultimately relies on histopathological examination.

Pathological Diagnosis and Immunohistochemistry

The definitive diagnosis of AMN rests on pathological examination of tissue specimens obtained through appendectomy, biopsy, or cytoreductive surgery. Histologically, AMNs are characterized by the presence of mucin. Immunohistochemical staining can aid in confirming the diagnosis and differentiating AMNs from other tumors. AMNs typically stain diffusely positive for CK20 and often negative for CK7. They are also commonly positive for MUC5AC and DPC4. This immunoprofile shares similarities with colorectal cancer, suggesting potential common pathogenic pathways.

Molecular Alterations in AMN

Molecular profiling of AMNs is increasingly being explored to understand their pathogenesis and identify potential therapeutic targets. Studies have revealed that AMNs frequently harbor mutations in the KRAS gene, suggesting this may be an early event in tumorigenesis. Mutations in TP53, MYC, SMAD4, and APC genes have also been reported. While AMNs share some molecular features with colorectal cancers, there are also distinct genomic signatures. Microsatellite instability (MSI) is less common in AMNs compared to colorectal cancer. Ongoing research is focused on identifying specific molecular alterations that may predict prognosis and response to therapy, paving the way for targeted treatment approaches in the future.

Management and Treatment Strategies for AMN

The management of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms is primarily guided by the stage and histologic grade of the tumor.

Treatment of Localized AMN

For localized AMNs, where the tumor is confined to the appendix, surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment. For low-grade tumors without evidence of extra-appendiceal spread, simple appendectomy is generally considered sufficient. However, in cases where the tumor involves the base of the appendix, is larger than 2 cm, exhibits high-grade histology, or invades through the muscularis propria, right hemicolectomy is recommended to ensure adequate tumor removal and minimize the risk of recurrence. Right hemicolectomy should also be considered if tumor margins are involved after initial appendectomy. The decision to perform right hemicolectomy is often based on a combination of factors, including tumor size, grade, location, and presence of adverse features like perforation or lymphovascular invasion.

Adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of localized AMN is not routinely recommended, particularly for low-grade, well-differentiated tumors. However, it may be considered in high-risk situations, such as poorly differentiated tumors (signet ring histology), tumors with lymph node involvement, or in cases of perforation. Fluorouracil (5-FU)-based chemotherapy regimens are typically used in these selected cases.

Management of AMN with Peritoneal Metastasis

The management of AMN with peritoneal metastasis, often presenting as pseudomyxoma peritonei, has evolved significantly over time. Historically, treatment was largely palliative, focusing on drainage of mucinous ascites. However, the introduction of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has revolutionized the treatment of this advanced disease.

Cytoreductive Surgery (CRS) and HIPEC

Cytoreductive surgery aims to remove all visible tumor deposits from the peritoneal cavity through peritonectomies and visceral resections. Completeness of cytoreduction is a critical prognostic factor, with optimal outcomes achieved when complete resection (CCR-0) is attained, meaning no visible residual disease remains. HIPEC is performed immediately after CRS and involves the intraoperative perfusion of heated chemotherapy agents into the abdominal cavity. HIPEC is designed to eradicate any residual microscopic disease and enhance local drug delivery while minimizing systemic toxicity. Commonly used HIPEC agents in AMN include mitomycin C, oxaliplatin, cisplatin, and 5-FU, used as single agents or in combination regimens.

The combination of CRS and HIPEC has demonstrated significant improvements in survival for patients with AMN and peritoneal metastasis, particularly for low-grade tumors. Reported 5-year survival rates for low-grade AMN with peritoneal spread treated with CRS and HIPEC range from 60% to 86% in patients achieving complete cytoreduction. However, survival rates are significantly lower with incomplete cytoreduction. Preoperative Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) scoring, based on imaging, can help predict the likelihood of achieving complete cytoreduction and guide surgical decision-making. A high PCI score (>20) may indicate a lower probability of achieving CCR.

While randomized controlled trials specifically for AMN are lacking, expert consensus and retrospective studies strongly support the survival benefit of CRS and HIPEC in appropriately selected patients with peritoneal metastasis from AMN. Optimal patient selection, complete cytoreduction, and specialized centers with expertise in CRS and HIPEC are crucial for maximizing treatment outcomes.

Role of Systemic Chemotherapy

The role of systemic chemotherapy in the management of AMN is complex and depends on the stage and grade of the disease.

Preoperative Chemotherapy: Current evidence generally does not support the routine use of preoperative systemic chemotherapy for resectable peritoneal metastasis from low-grade AMN. Retrospective studies have suggested that preoperative chemotherapy may be associated with worse outcomes in this setting, potentially due to selection bias, limited chemotherapy efficacy, or delay in definitive surgical intervention. However, for high-grade appendiceal adenocarcinomas with peritoneal metastasis, preoperative chemotherapy may be considered to potentially downstage the disease and improve resectability.

Palliative Systemic Chemotherapy: Systemic chemotherapy is primarily reserved for patients with recurrent or unresectable AMN, or for those who are not candidates for CRS and HIPEC. Fluorouracil-based regimens are commonly used, often in combination with oxaliplatin or mitomycin C. However, the response rates to systemic chemotherapy in AMN, particularly in low-grade tumors, are often modest. Targeted therapies, such as EGFR inhibitors and anti-angiogenic agents, have not been extensively studied in AMN, and their role remains investigational. Ongoing research is exploring the potential of molecularly targeted therapies based on the specific genetic alterations identified in AMNs.

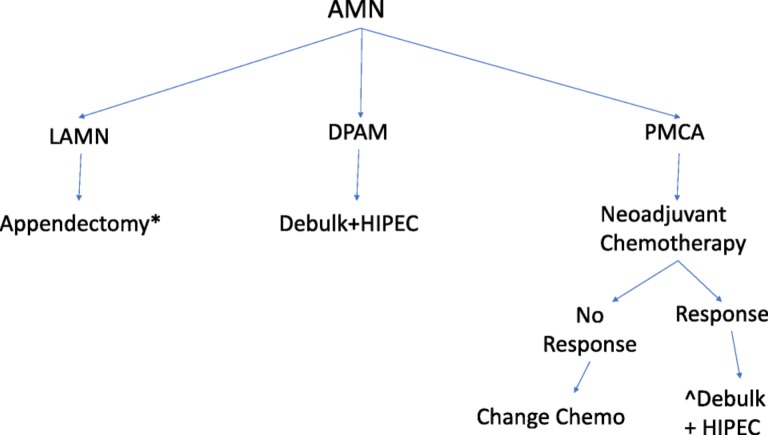

Figure 7. Treatment algorithm for appendiceal mucinous neoplasms based on histologic subtype and stage, outlining surgical and chemotherapy approaches including HIPEC.

Conclusion

Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms are a heterogeneous group of tumors with increasing incidence, posing diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Treatment strategies are primarily determined by the stage and histologic grade of the disease. For early-stage, low-grade AMNs, surgical resection alone is often sufficient. However, for advanced-stage disease with peritoneal metastasis, cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC have emerged as the standard of care, offering the potential for long-term survival in selected patients. High-grade AMNs and recurrent/unresectable disease remain challenging to treat, and further research is needed to develop effective systemic therapies, including molecularly targeted approaches. Future prospective clinical trials and translational research focusing on the molecular characterization of AMNs are crucial to refine treatment algorithms and improve outcomes for patients with this rare and complex malignancy.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Walid L. Shaib, Bassel F. El‐Rayes

Collection and/or assembly of data: Walid L. Shaib, Rita Assi, Volkan Adsay

Manuscript writing: Walid L. Shaib, Ali Shamseddine, Olantunji B. Alese, Charles III Staley, Bahar Memis, Tonios Bekaii‐Saab

Final approval of manuscript: Volkan Adsay, Tonios Bekaii‐Saab, Bassel F. El‐Rayes

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.