Introduction

Asperger’s Syndrome, a condition within the autism spectrum disorders (ASD), is characterized by difficulties in social interaction, circumscribed interests, and repetitive behaviors. While historically considered primarily a childhood diagnosis, recognition of Asperger’s in adults is increasingly important. Individuals with Asperger’s often face significant challenges in social, professional, and personal aspects of life, and understanding the nuances of Aspergers Diagnosis As An Adult is crucial for effective support and intervention.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of Asperger’s Syndrome in adulthood. Drawing upon a review of relevant literature and clinical experience, we will explore the diagnostic process, characteristic symptoms, prevalence, underlying factors, and current approaches to treatment and support for adults living with Asperger’s. Recognizing Asperger’s in adults is the first step towards unlocking appropriate interventions and improving quality of life.

Methods

The information presented in this article is synthesized from a selective review of medical literature indexed in Medline. Keywords used for the literature search included “Asperger’s syndrome,” “autism,” “prevalence,” “diagnostic,” “comorbidity,” “pathogenesis,” and “brain.” This review encompassed review articles, original research articles, and pertinent reference books published up to May 2008. Furthermore, the insights are enriched by clinical experiences gathered from a specialized outpatient clinic dedicated to adults with Asperger’s Syndrome, providing a practical perspective on the challenges and manifestations of this condition in adult life.

Prevalence

Estimates of Asperger’s Syndrome prevalence in childhood range from 0.02% to 0.03% [1, 2], with a notable gender disparity of approximately 8:1, favoring males [3]. While robust prevalence studies specifically focusing on adults are still lacking, the persistence of core Asperger’s symptoms throughout life [4] suggests that the condition remains a relevant consideration in the adult population. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that Asperger’s Syndrome is not significantly less prevalent in adults than in children, highlighting the ongoing need for recognition and appropriate diagnostic and support systems for adults.

Diagnosis and Symptoms

Currently, there are no definitive biological markers or somato-organic findings to confirm Asperger’s Syndrome. The diagnosis remains fundamentally clinical, relying on meticulous evaluation of psychopathological findings and a comprehensive medical and psychiatric history, with particular emphasis on childhood development. Asperger’s Syndrome gained formal recognition as a “pervasive developmental disorder” (F84.5) in the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) in 1993, and subsequently in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) of the American Psychiatric Association in 1994 (see Box 1).

Box 1. Diagnostic criteria for Asperger’s syndrome according to DSM-IV (shortened).

-

Qualitative impairment in social interaction, as manifested by at least two of the following:

- Marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors such as eye-to eye gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction

- Failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level

- Lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people

- Lack of social or emotional reciprocity

-

Restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities, as manifested by at least one of the following:

- Encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus

- Apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional routines or rituals

- Stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms

- Persistent preoccupation with parts of objects

-

The disturbance causes clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

-

There is no clinically significant general delay in language e.g., single words used by age two years, communicative phrases used by age three years).

-

There is no clinically significant delay in cognitive development.

-

Criteria are not met for another specific pervasive developmental disorder or schizophrenia.

The onset of symptoms typically becomes apparent after the age of three. Due to potential overlap with other conditions, aspergers diagnosis as an adult requires expertise. It should be conducted by a psychiatrist or psychotherapist specializing in ASD, or a child and adolescent psychiatrist when assessing children and teenagers.

In addition to clinical psychiatric assessment, standardized questionnaires can aid in the diagnostic process. The Adult Asperger Assessment (AAA) is specifically designed for aspergers diagnosis as an adult [5]. It incorporates two screening tools, the Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) and the Empathy Quotient (EQ), along with expanded DSM-IV criteria (see Box 2).

Box 2. DSM-IV extensions after Adult Asperger Assessment (AAA) (modified).

Ad A) Difficulties in understanding social situations and other people’s thoughts and feelings

Ad B) Tendency to think of issues as being black and white, rather than considering multiple perspectives in a flexible way

Additionally: Qualitative impairments in verbal or nonverbal communication with at least three of the following symptoms:

- Tendency to turn any conversation back on to self or own topic of interest

- Marked impairment in the ability to initiate or sustain a conversation with others. Cannot see the point of superficial social contact, niceties, or passing time with others, unless there is a clear discussion point/debate or activity.

- Pedantic style of speaking, inclusion of too much detail

- Inability to recognize when the listener is interested or bored

- Frequent tendency to say things without considering the emotional impact on the listener

Additionally: Impairment in at least one of the criteria relating to childhood imagination:

- Lack of varied, spontaneous make believe play appropriate to developmental level

- Inability to tell, write or generate spontaneous, unscripted or unplagiarized fiction

- Either lack of interest in fiction (written, or drama) appropriate to developmental level or interest in fiction is restricted to its possible basis in fact (e.g. science fiction, history, technical aspects of film)

The AQ evaluates five domains relevant to Asperger’s Syndrome across 50 items:

- Social skills

- Attention switching

- Attention to detail

- Communication

- Imagination (cut-off score >32 points).

The EQ measures the capacity for empathy, specifically the ability to share and understand another’s emotional state (cut-off score 6).

One of the challenges in aspergers diagnosis as an adult is the potential for recall bias and gaps in childhood memories. Gathering information from parents or siblings about the individual’s childhood personality traits can be invaluable. School records, including report cards, may also offer supportive evidence, sometimes containing comments like “…has problems integrating into the class.” However, such remarks are not solely indicative of Asperger’s and should be considered as supplementary data within a comprehensive assessment.

Clinical observations during examinations of adults often reveal characteristic traits. Individuals may initially appear inattentive to instructions or seem awkward in navigating the consultation room. Facial expressions and speech intonation can be perceived as monotone or lacking in স্বাভাবিকতা [7]. Conversely, their spoken language may be grammatically precise and lexically rich. Direct eye contact is often limited [7], with individuals frequently looking around the room during conversation. Their narratives tend to be highly detailed, blurring the lines between essential and trivial information. Emotional cues from the examiner, such as smiles or humorous remarks, may not elicit reciprocal responses.

Clinical experience highlights the significant impact of Asperger’s symptoms on the social and professional lives of adults. Many adults with Asperger’s experience social isolation and limited meaningful social connections. Online interactions, particularly within Asperger’s forums, can provide a sense of community, offering a platform to communicate with individuals who share similar thought patterns and appreciate literal communication, minimizing the demands of interpreting nonverbal cues.

Relationship challenges are particularly common [8]. Difficulties in empathy can hinder the ability to initiate and navigate romantic relationships. Individuals may unintentionally appear self-centered or emotionally distant to partners. The inherent demands of close relationships, such as the expectation of reciprocal emotional communication and empathy, can feel overwhelming. Consequently, some individuals may gravitate towards long-distance relationships, which offer limited but controlled interaction. Sexuality also presents a complex area. Some individuals with Asperger’s may have a diminished need for physical intimacy or even aversion to it, while others experience insecurities regarding sexual expression despite having typical sexual desires [8, 9], given that sexual intimacy is deeply intertwined with mutual empathy. However, it’s important to note that some adults with Asperger’s do successfully build stable relationships and families.

Professionally, two distinct trajectories are observed. Some individuals struggle with workplace social dynamics and interactions with colleagues and clients. A perceived blunt or overly direct communication style can lead to interpersonal conflicts, and adapting to varied workplace demands may be challenging. Conversely, others achieve significant professional success, often leveraging their specialized interests, particularly in fields like information technology. Strong cognitive abilities can be a significant asset in achieving both professional and personal goals, as illustrated in the clinical example in Box 3.

Box 3. Clinical example/case report.

Mr. M, a 35-year-old, described himself as a lifelong “outsider and loner.” He had never formed close friendships. Despite extensive reading on social behavior to better understand his environment, he consistently felt overwhelmed by the “riddle” of interpersonal communication. He visualized faces as static, like “passport photos with name inset,” lacking dynamic expression. He painstakingly deciphered emotions by analyzing minute facial features, such as the angles of the mouth and eyebrows. He interpreted language literally, leading to frequent misunderstandings. He only realized in adulthood that his parents’ term “Stubenhocker” (couch potato) was not a literal description of him as furniture. He ended his only romantic relationship, a weekend affair, concluding that “the benefits didn’t justify all the effort,” yet expressed a desire for a life partner.

Professionally, he found his niche. As a child, he dedicated countless hours to building complex Lego structures and memorizing cartoon titles. As a teenager, he self-taught computer programming and, despite lacking formal training, became highly successful in the IT sector. Programming provided “deep satisfaction,” while the “inevitable social interaction” with colleagues was a significant source of stress.

Routines were crucial for him; deviations were rare. He followed a fixed sequence for dressing since childhood and adhered to a rigid morning routine at work. Even minor disruptions to these routines were profoundly upsetting, causing him to feel “derailed.” Overall, engaging in life “outside his private sphere” was the most significant challenge for him.

Differential Diagnosis and Comorbidities

In differentiating Asperger’s Syndrome, it’s important to consider other conditions. Early childhood autism (Kanner’s Syndrome) often presents with more pronounced nonverbal communication deficits and delayed or absent speech, along with more extensive and stereotypical behaviors [10]. The overall level of impairment in Kanner autism is typically more significant than in Asperger’s. The distinction between Asperger’s Syndrome and high-functioning autism has been debated. While high-functioning autism shares similarities with Asperger’s, individuals with high-functioning autism often exhibit delays in cognitive and language development compared to those with Asperger’s. Recent research suggests that behavioral profiles may not fundamentally differ between Asperger’s Syndrome and high-functioning autism [11].

Differentiating Asperger’s Syndrome from schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders can also be complex. Both personality disorders involve social withdrawal and a preference for solitary lifestyles. Schizoid personality disorder is characterized by emotional detachment, limited emotional expression, and reduced capacity for pleasure. Schizotypal personality disorder includes eccentric behavior, often with magical thinking and suspiciousness in relationships. However, neither disorder typically features the intense, specific interests or the pronounced insistence on routines that are hallmarks of Asperger’s.

Schizophrenic psychosis can also manifest with social withdrawal and reduced empathy. Key differentiating features of schizophrenia include disorganized thinking and delusions, which are not characteristic of Asperger’s. The onset of Asperger’s symptoms is in early childhood, whereas conditions like hebephrenic schizophrenia typically emerge in adolescence or later. The absence of “productive” psychotic symptoms (hallucinations, delusions) is also crucial in distinguishing Asperger’s from simple schizophrenia.

Borderline personality disorder, particularly in women, can present diagnostic challenges due to shared difficulties in empathy and interpreting nonverbal cues. However, borderline personality disorder is primarily characterized by intense mood instability, which is not a core feature of Asperger’s, and the specific, circumscribed interests and detail-oriented thinking seen in Asperger’s are usually absent.

Depression is a significant comorbidity in adults with Asperger’s, often arising from the challenges in social and professional life. Diagnosing comorbid depression can be complicated by overlapping symptoms like social withdrawal and communication difficulties [12, 13]. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [3] and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [14] are also frequently co-occurring conditions.

Etiology and Theoretical Concepts

The precise causes of Asperger’s Syndrome remain incompletely understood, but a multifactorial etiology is highly probable. Genetic factors are believed to play a significant role, with chromosomes 1, 3, and 13 implicated in susceptibility [15]. Perinatal complications may also contribute to the development of the condition [16]. Remschmidt and Kamp-Becker’s theoretical model [7] proposes that deficits in three core cognitive domains underlie the characteristic features of autism spectrum disorders (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model of Deficient Abilities in Asperger’s Syndrome

- Theory of Mind

- Central Coherence

- Executive Functions

Theory of Mind

“Theory of mind” is a neuroscientific concept referring to the capacity for empathy. It encompasses both the understanding that others have their own distinct thoughts, beliefs, and emotions, and the ability to empathize with those mental states. Individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome often exhibit significant impairments in theory of mind. Neurophysiological studies suggest that theory of mind abilities are associated with brain regions such as the medial prefrontal cortex [17]. Functional imaging studies in adults with Asperger’s have shown reduced activity in the left medial prefrontal cortex during tasks requiring theory of mind [18]. The amygdala, a key structure in emotional processing, and the fusiform face area, specialized for facial recognition, also show reduced activity in individuals with Asperger’s or early childhood autism [19, 20].

The mirror neuron system is considered particularly relevant to empathy and theory of mind. This neural network activates both when performing an action and when observing the same action performed by another [21]. It is hypothesized that the mirror neuron system may be functionally impaired in individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome [22].

Central Coherence

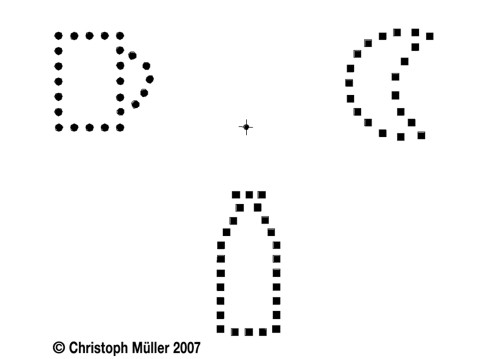

Central coherence describes the cognitive ability to integrate individual sensory details into a meaningful overall context – to see the “big picture” [Figure 2]. A statement like “I see hundreds of individual trees, but I cannot see a forest” could be illustrative of this concept in Asperger’s. Individuals with reduced central coherence tend to focus on details and struggle to grasp the broader context. The specific neural correlates of this phenomenon are not yet fully understood.

Figure 2.

Central Coherence Testing Example

Testing central coherence. The patient is given the task to assign one of the two images at the top to the image at the bottom. People with a holistic perception will assign the beaker to the bottle at the bottom. Detail-oriented perception in poorly developed central coherence will lead to the decision that the top right object matches the bottom object as they both consist of squares. The task is taken from a scientific study and not suited for use in routine diagnostics. From: Müller C: Autismus und Wahrnehmung. Eine Welt aus Farben und Details. Marburg: Tectum 2007. With permission from Tectum Publishers, Marburg [23]

Executive Functions

Executive functions encompass a range of higher-level cognitive skills crucial for goal-directed behavior, including planning, self-monitoring, impulse control, attentional focus, and flexible problem-solving. Executive function deficits are frequently observed in individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome. This can manifest as inflexibility in attention and difficulty adapting to new situations or applying learned behaviors in novel contexts. The prefrontal cortex is recognized as a key neuroanatomical substrate for executive functions [24].

It’s important to acknowledge that while research has identified potential functional differences in specific brain areas, as outlined above, a comprehensive neurobiological model for Asperger’s Syndrome is still evolving.

Therapy

Not all individuals with Asperger’s Syndrome require or seek treatment. However, when symptoms significantly impact quality of life, particularly in the presence of comorbid conditions, a multimodal therapeutic approach combining symptom-focused pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions is generally recommended. For managing impulsivity, atypical antipsychotics or mood stabilizers may be considered. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be helpful in treating comorbid depression or obsessive-compulsive symptoms [7, 10]. In cases of comorbid ADHD, stimulant medications have shown positive outcomes in some instances [14]. Currently, there are no medications specifically designed to target the core features of Asperger’s Syndrome itself.

While empirically validated, specific psychotherapeutic protocols for aspergers diagnosis as an adult are still under development, existing therapeutic approaches used effectively with children and adolescents with Asperger’s can provide valuable guidance. Behavioral therapies like TEACCH (Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication-handicapped Children) and ABA (Applied Behavior Analysis) are considered beneficial. These programs focus on enhancing social and communication skills through clear, direct instructions and step-by-step learning strategies. Adapting the individual’s environment to accommodate their specific challenges is an additional therapeutic goal [7].

Klin and Volkmar [25] propose the following therapeutic principles for adults with Asperger’s Syndrome:

- Social perception training and discussion

- Structured, step-by-step coaching in problem-solving and daily living skills

- Practicing social behaviors in novel situations

- Facilitating generalization of learned skills to different contexts

- Fostering a concrete sense of identity based on everyday behaviors and accomplishments

- Analyzing frustration-inducing situations and exploring the individual’s impact on others

- Integrating supportive therapies such as occupational therapy or physiotherapy.

In summary, structured, directive therapeutic interventions that utilize concrete, real-life examples to explore social situations appear to be particularly effective [8]. Psychodynamic approaches may also be beneficial, especially in addressing common issues such as low self-esteem often experienced by adults with Asperger’s.

Key messages.

- Core symptoms of Asperger’s Syndrome include reduced socioemotional reciprocity, specific interests, and repetitive behaviors.

- Aspergers diagnosis as an adult relies on thorough anamnesis, heteroanamnesis, and clinical-psychiatric examination.

- The etiology of Asperger’s Syndrome is multifactorial, with deficits in theory of mind, central coherence, and executive functions playing significant roles.

- Symptom-focused pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy offer effective therapeutic strategies.

- Not every case of Asperger’s Syndrome requires clinical intervention or treatment.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Dr. Birte Twisselmann.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

[1] Gillberg C, Steffenburg S, Schaumann H. Is autism more common now than ten years ago? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48: 91-5.

[2] Szatmari P, Bremner R, Nagy J. Asperger’s syndrome: a review of clinical features. Can J Psychiatry 1989; 34: 554-60.

[3] Tsai LY. Asperger’s syndrome: children and adolescents. In: Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR, eds. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley; 1997: 196-207.

[4] Nordin V, Gillberg C. The long-term course of autistic disorders: is Asperger syndrome different from other autism subtypes? J Autism Dev Disord 1998; 28: 249-56.

[5] Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Jolliffe T. What is the Adult Asperger Assessment (AAA)? Version 1.5. Southampton: University of Southampton; 1997.

[6] Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S. The empathy quotient (EQ). J Autism Dev Disord 2004; 34: 163-75.

[7] Remschmidt H, Kamp-Becker I. Asperger-Syndrom und hochfunktionaler Autismus im Kindes-, Jugend- und Erwachsenenalter. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag; 2006.

[8] Attwood T. Asperger’s syndrome: a guide for parents and professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1998.

[9] Schlottmann R, Bölte S, Poustka F. Asperger-Syndrom im Erwachsenenalter. Dtsch Arztebl 2006; 103: A1680-3.

[10] Volkmar FR, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen DJ. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. 3rd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

[11] Szatmari P, Bryson SE, Streiner DL, Wilson FJ. Two pathways to autism: genetic versus pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42: 589-95.

[12] Ghaziuddin M, Leininger J, Tsai L. Comorbidity of Asperger syndrome: a preliminary report. J Autism Dev Disord 1991; 21: 431-5.

[13] Wing L. Asperger’s syndrome: an historical perspective. In: Frith U, ed. Autism and Asperger syndrome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991: 92-103.

[14] Sinzig J, Morsch D, Bruning N, Schmidt MH, Lehmkuhl U. ADHD and autism: are there differences in attention profile? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008; 17: 159-66.

[15] Betancur C, Leboyer M, Gillberg C. Autism spectrum disorders: evidence for clinical and genetic heterogeneity. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 14: 73-91.

[16] Gillberg C, Rasmussen P, Wahlstrom G, et al. Perinatal risk factors in autism and Asperger syndrome: a population-based study. Early Hum Dev 2001; 61: 165-84.

[17] Brunet E, Sarfati Y, Hardy-Bayle MC, Decety J. Abnormal activation of the prefrontal cortex during theory-of-mind tasks. Nat Neurosci 2000; 3: 724-30.

[18] Happé F, Ehlers S, Fletcher P, et al. ‘Theory of mind’ in the brain. Evidence from a PET scan study of Asperger syndrome. Brain 1996; 119: 407-21.

[19] Critchley HD, Daly EM, Bullmore ET, et al. The functional neuroanatomy of social behaviour: changes in cerebral blood flow when people with autism process facial expressions. Brain 2000; 123: 2203-12.

[20] Schultz RT, Gauthier I, Klin A, et al. Abnormal ventral temporal cortical activity during face discrimination among individuals with autism and Asperger syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57: 331-40.

[21] Rizzolatti G, Craighero L. The mirror-neuron system. Annu Rev Neurosci 2004; 27: 169-92.

[22] Oberman LM, Ramachandran VS. The mirror neuron system and autism spectrum disorders: breaking the broken mirror. Soc Neurosci 2007; 2: 193-205.

[23] Müller C: Autismus und Wahrnehmung. Eine Welt aus Farben und Details. Marburg: Tectum 2007.

[24] Luria AR. Higher cortical functions in man. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books; 1981.

[25] Klin A, Volkmar FR. Asperger syndrome. In: Volkmar FR, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen DJ, eds. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. 3rd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2005: 71-103.