The atoll sign, also known as the reversed halo sign (RHS), is a distinctive pattern observed on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans of the lungs. Radiologically, it is characterized by a central area of ground-glass opacity surrounded by a ring of denser consolidation. Initially considered highly specific for cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), it is now recognized in a diverse spectrum of pulmonary conditions, both neoplastic and non-neoplastic. Understanding the Atoll Sign Differential Diagnosis is crucial for accurate radiological interpretation and guiding clinical management.

First described in the context of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, the atoll sign, with its resemblance to a coral atoll, was initially believed to be pathognomonic for this condition. However, subsequent research has demonstrated its presence in a wide array of pulmonary diseases. While this reduces its specificity, the atoll sign remains a valuable diagnostic clue. When interpreted in conjunction with patient history, clinical context, and other accompanying radiological findings, it significantly narrows the differential diagnosis. This comprehensive guide aims to explore the various conditions associated with the atoll sign, offering insights into its differential diagnosis and emphasizing its clinical significance.

Infectious Diseases Associated with the Atoll Sign

Invasive Fungal Pneumonia

Invasive fungal pneumonias (IFPs) are severe infections with high morbidity and mortality, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. While invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is the most frequently encountered IFP, infections caused by other angioinvasive molds like Zygomycetes (including Rhizopus and Mucor) are increasingly being observed. Timely initiation of aggressive antifungal therapy is critical for improving patient outcomes. Differentiating between IPA and pulmonary zygomycosis (PZ) is paramount, as standard antifungal regimens for presumed fungal pneumonia often target aspergillosis, and voriconazole, the preferred agent for IPA, is ineffective against PZ.

Clinically, PZ and IPA can present with similar features. However, a high index of suspicion for PZ should be maintained in immunosuppressed patients exhibiting the atoll sign on CT scans, especially when accompanied by sinusitis and in patients receiving voriconazole prophylaxis. While the atoll sign is more strongly associated with PZ, it can also be observed in IPA.

In the context of IFP, the atoll sign is considered an early indicator resulting from pulmonary infarction. As the disease progresses into the subacute phase, the air-crescent sign typically emerges. Additional radiological findings that may accompany the atoll sign in IFP include pulmonary nodules larger than 1 cm in diameter and pleural effusions.

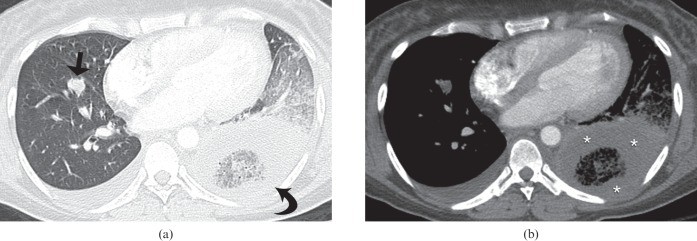

Figure 1. CT image illustrating the atoll sign (reversed halo sign) in the left upper lobe of a 22-year-old male with precursor B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia, indicative of pulmonary zygomycosis.

Figure 2. High-resolution CT image of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a 54-year-old female with multiple myeloma, demonstrating the atoll sign (reversed halo sign) in the left lower lobe along with a right lower-lobe pulmonary nodule and a small right pleural effusion.

Endemic Fungal Infections

Paracoccidioidomycosis, also known as South American blastomycosis, is the most prevalent systemic fungal infection in Latin America, particularly in Brazil. The atoll sign has been observed in up to 10% of paracoccidioidomycosis cases. Lung involvement occurs in approximately 80% of cases, and residual fibrotic lesions are seen in about 60%. Histopathological analysis of lung biopsies from patients with paracoccidioidomycosis exhibiting the atoll sign reveals that the central ground-glass opacity corresponds to inflammatory infiltration predominantly affecting the alveolar septa. In contrast, the peripheral ring of consolidation consists of dense intra-alveolar inflammatory infiltrate.

The atoll sign has also been reported, albeit less frequently, in other endemic fungal infections such as histoplasmosis and cryptococcosis. In patients from endemic regions for fungal infections, the presence of the atoll sign should prompt consideration of these specific fungal etiologies.

Figure 3. CT image depicting atoll sign (reversed halo sign) lesions and bilateral small, poorly defined pulmonary nodules in a 49-year-old male from a rural area in Brazil with paracoccidioidomycosis.

Pneumocystis jiroveci Pneumonia

Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PJP) remains a significant opportunistic infection in individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), although its incidence has decreased with the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy. The atoll sign has been infrequently reported in HIV-positive patients with PJP. When present, it adds to the diverse radiological manifestations of this infection in immunocompromised hosts.

Tuberculosis

While tuberculosis prevalence had been declining, a resurgence has occurred since the mid-1980s, linked to the HIV epidemic and the emergence of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. Pulmonary tuberculosis can also manifest with the atoll sign, as first described in a case involving a 15-year-old male. Associated findings in tuberculosis cases with the atoll sign can include centrilobular nodules and lymphadenopathy in the subcarinal and left hilar regions. In another reported case in an adult female, accompanying CT findings were pulmonary nodules and cavitary consolidation.

A distinctive feature observed in tuberculosis and other granulomatous infections, including schistosomiasis and cryptococcosis, is the nodular appearance of the ring component of the atoll sign. Histologically, these nodules correspond to granulomas, which can be a valuable differentiating feature from organizing pneumonia in the atoll sign differential diagnosis, suggesting active granulomatous disease.

Figure 4. High-resolution CT image of tuberculosis in a 59-year-old female, showing bilateral small centrilobular nodules, tree-in-bud opacities, and atoll sign (reversed halo sign) lesions with a nodular ring of consolidation.

Bacterial Pneumonia

The atoll sign has been sporadically reported in community-acquired pneumonia, including pneumococcal pneumonia, psittacosis, and Legionnaire’s disease. In bacterial pneumonia, the atoll sign appears to be a later finding, observed during the resolution phase. In this context, it is less helpful for immediate treatment decisions, unlike in invasive fungal infections where it can guide antifungal selection.

It’s important to note that infections can histologically trigger organizing pneumonia, indistinguishable from cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Therefore, in some reported cases of the atoll sign associated with bacterial pneumonia in immunocompetent individuals, where biopsies were not performed, the atoll sign may represent secondary organizing pneumonia initiated by the infection rather than a direct manifestation of the infectious process itself.

Non-Infectious, Non-Neoplastic Diseases Presenting with Atoll Sign

Organizing Pneumonia

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) is the most commonly identified condition associated with the atoll sign in immunocompetent patients. Studies have reported the atoll sign in up to 19% of HRCT scans of patients diagnosed with COP. Secondary organizing pneumonia can also exhibit the atoll sign. Histopathological correlation in early COP cases with the atoll sign revealed that the central ground-glass opacity corresponded to alveolar septal inflammation and cellular debris, while the peripheral consolidation represented organizing pneumonia within the alveolar ducts.

Figure 5. CT scan of organizing pneumonia in a 53-year-old male with graft-versus-host disease, demonstrating bilateral peripheral and peribronchovascular consolidative opacities with the atoll sign (reversed halo sign).

Non-Specific Interstitial Pneumonia

Non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) is a chronic interstitial lung disease that can be idiopathic or associated with collagen vascular diseases, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, or drug toxicity. NSIP ranges from predominantly interstitial inflammation (cellular NSIP) to fibrosis (fibrotic NSIP). The atoll sign has been infrequently reported in cases of cellular NSIP, highlighting its diverse radiological presentations.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown cause, affecting the lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes in the majority of patients. The atoll sign is an atypical manifestation of sarcoidosis, reported in a limited number of cases. Similar to granulomatous infections, sarcoidosis-related atoll signs can exhibit small nodules within the ground-glass opacity and around the peripheral consolidation. Associated CT findings in sarcoidosis with the atoll sign may include larger nodules, subpleural nodules, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Histologically, the atoll sign in sarcoidosis can arise from either non-caseating granulomatous inflammation or secondary organizing pneumonia. The presence of small nodules within the atoll sign favors a granulomatous process over organizing pneumonia in the differential diagnosis.

Figure 6. High-resolution CT image of sarcoidosis in a 44-year-old female, showing bilateral nodular opacities with the atoll sign (reversed halo sign) and small pulmonary nodules with a perilymphatic distribution.

Lipoid Pneumonia

Lipoid pneumonia is a rare condition resulting from lipid accumulation in the alveoli. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia is caused by inhalation or aspiration of oils, while endogenous lipoid pneumonia is often associated with bronchial obstruction. A case of exogenous lipoid pneumonia due to chronic paint spray inhalation presented with the atoll sign on HRCT scan after an initial diagnosis of irregular pulmonary nodules. It’s suggested that the atoll sign in this context might represent organizing pneumonia secondary to lipoid pneumonia, given the time lag between initial diagnosis and atoll sign appearance.

Wegener’s Granulomatosis

Wegener’s granulomatosis (now known as granulomatosis with polyangiitis) is a rare necrotizing vasculitis associated with elevated cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA) titers. It commonly affects the upper respiratory tract, lungs, and kidneys. The atoll sign has been reported in Wegener’s granulomatosis, along with other findings like nodular opacities, ground-glass opacities, consolidation, and cavitation. In this condition, the atoll sign may represent an intermediate stage preceding cavitation, similar to what is seen in invasive fungal pneumonia and pulmonary infarction.

Pulmonary Embolism

Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is a common and potentially life-threatening condition. Pulmonary infarction, a complication of PE, occurs in approximately 10% of cases and typically presents as a wedge-shaped consolidation on CT. The atoll sign can be observed in pulmonary infarction secondary to PE and may precede cavitation of the infarcted tissue.

Figure 7. CT images illustrating acute pulmonary embolism with pulmonary infarction in a 64-year-old female, demonstrating the atoll sign (reversed halo sign) in the right lower lobe and a thrombus in the right main pulmonary artery.

Neoplastic Diseases and the Atoll Sign

Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is a rare Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorder with potential progression to lymphoma. Pulmonary nodules, which can subsequently evolve into the atoll sign, have been reported in patients with lymphomatoid granulomatosis. This highlights the importance of considering lymphoproliferative disorders in the atoll sign differential diagnosis, particularly when pulmonary nodules are present.

Lung Adenocarcinoma

Lung adenocarcinoma, a common type of lung cancer, can present on CT scans in various forms, including consolidation, solitary or multiple pulmonary nodules (solid, mixed, or pure ground-glass). Adenocarcinomas with predominant ground-glass components tend to grow slowly and often correspond to a lepidic growth pattern histologically. The atoll sign can be seen in lung adenocarcinomas when a ground-glass component is centrally located within the lesion.

Figure 8. CT image demonstrating multifocal pulmonary adenocarcinoma in a 70-year-old female, showing bilateral pulmonary nodules with the atoll sign (reversed halo sign) and ground-glass pulmonary nodules.

Metastatic Disease

Pulmonary metastases typically manifest as multiple, round nodules in the periphery of the lungs. However, atypical presentations are not uncommon, including cavitation, calcification, hemorrhage, and air-space patterns. The atoll sign is another atypical manifestation of pulmonary metastatic disease. In patients with a known primary malignancy, the presence of the atoll sign should raise suspicion for metastatic disease. However, it is crucial to differentiate this from organizing pneumonia, which can be a complication of chemotherapy.

Figure 9. CT scan showing multiple bilateral lesions with the atoll sign (reversed halo sign) in a 73-year-old male with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, confirmed by biopsy.

Atoll Sign in Post-Treatment Changes

Radiofrequency Ablation

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of pulmonary neoplasms can result in a range of CT findings, including circumferential ground-glass opacity around the treated lesion, cavitation, and pleural thickening. Following RFA, the atoll sign has been observed, typically around 6 weeks post-procedure. It is postulated that the central ground-glass opacity in this context represents coagulation necrosis of the tumor and adjacent lung tissue. Recognizing the atoll sign in the post-RFA setting is crucial to avoid misinterpreting it as tumor recurrence.

Figure 10. CT images illustrating the atoll sign (reversed halo sign) following radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of a pulmonary adenocarcinoma in a 64-year-old female, observed one month post-RFA.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation-induced lung disease (RILD) is a common complication of thoracic radiation therapy. In the acute phase of RILD, typically occurring within 4-12 weeks post-radiation, CT findings often include ground-glass opacities and consolidation. The atoll sign can also be seen in this acute phase. When the atoll sign appears at the tumor site, it likely represents tumor necrosis. When observed outside the tumor location but within the radiation field, it may be due to radiation-related inflammation, pulmonary necrosis, or secondary organizing pneumonia triggered by radiation injury. In the context of radiation therapy, the atoll sign should be differentiated from infection or tumor recurrence.

Figure 11. CT images showing the atoll sign (reversed halo sign) following proton radiation therapy for a poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in a 71-year-old male, indicating tumor necrosis.

Figure 12. CT images illustrating the atoll sign (reversed halo sign) following radiation therapy for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer in a 59-year-old female, consistent with radiation pneumonitis.

Clinical Application of the Atoll Sign in Differential Diagnosis

While the atoll sign is not as specific as initially thought, its clinical utility lies in narrowing the differential diagnosis when considered alongside patient demographics, clinical history, and other radiological findings. This is particularly relevant in immunocompromised patients. In severely immunocompromised individuals, the presence of the atoll sign should raise a strong suspicion for invasive fungal pneumonia, especially pulmonary zygomycosis, until proven otherwise. Early diagnosis and targeted antifungal therapy are critical in this population.

In patients with AIDS, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia should be considered, especially if the atoll sign is associated with diffuse ground-glass opacities. Tuberculosis should be suspected when the atoll sign exhibits a nodular ring and is accompanied by centrilobular nodules or endobronchial spread patterns, especially in high-risk individuals. In patients with known extrapulmonary malignancies, the atoll sign is more likely to represent metastatic disease. However, organizing pneumonia, triggered by chemotherapy, should also be considered in this setting. In primary lung cancer, particularly adenocarcinoma with lepidic growth, the atoll sign can be observed, and the slow progression typical of these tumors should raise suspicion. In post-treatment scenarios, the atoll sign often indicates pulmonary infarction or inflammation.

By integrating clinical and radiological data, radiologists can effectively utilize the atoll sign to guide differential diagnosis, potentially obviating the need for biopsy in selected cases, particularly in immunosuppressed patients.

Figure 13. A differential diagnosis algorithm summarizing the various conditions associated with the atoll sign (reversed halo sign), guiding diagnostic considerations based on clinical and radiological context.

Conclusion

The atoll sign, while not specific to a single condition, is a significant radiological finding in a range of pulmonary diseases. Its recognition on CT scans prompts a focused differential diagnosis. By carefully correlating the atoll sign with the patient’s clinical history, risk factors, and other accompanying radiological features, clinicians can effectively narrow the diagnostic possibilities. This approach aids in timely and appropriate clinical decision-making, potentially reducing the need for invasive procedures and improving patient management in various clinical scenarios associated with the atoll sign.