Introduction to Axillary Mass Evaluation

The axilla, a complex anatomical space, is a frequent site for palpable masses, often prompting patient concern and clinical investigation. Imaging plays a pivotal role in evaluating axillary symptoms, particularly in the context of newly diagnosed breast cancer and the investigation of palpable axillary lumps. A thorough understanding of axillary anatomy and a systematic approach to imaging interpretation are essential for formulating an accurate differential diagnosis and guiding appropriate patient management. This article provides a comprehensive review of the indications for axillary imaging, explores optimal scanning techniques and image-guided interventions, and presents a detailed differential diagnosis of axillary masses, emphasizing key imaging findings. Accurate differentiation of axillary pathologies is crucial to avoid unnecessary procedures and ensure timely and effective treatment.

Decoding Axillary Anatomy: Foundations for Diagnostic Accuracy

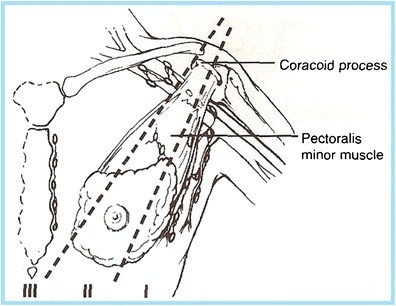

A precise grasp of the axillary anatomy is paramount for radiologists and clinicians interpreting axillary imaging. The axilla houses a diverse array of structures, including the axillary artery and vein, the brachial plexus, lymph nodes, adipose tissue, accessory breast tissue, and cutaneous and subcutaneous glands. Its anatomical boundaries are clearly defined: superiorly by the clavicle, scapula, and first rib; posteriorly by the subscapularis, teres major, and latissimus dorsi muscles; anteriorly by the pectoralis major and minor muscles; medially by the serratus anterior and the first four ribs; and laterally by the coracobrachialis and the short head of the biceps muscle. For breast imagers, the axillary lymph nodes are of primary concern (Fig. 1). These nodes are strategically categorized into three levels, crucial for staging and management, particularly in breast cancer:

- Level I: Lymph nodes situated lateral and inferior to the pectoralis minor muscle.

- Level II: Lymph nodes located beneath the pectoralis minor muscle.

- Level III: Lymph nodes positioned deep and medial to the medial border of the pectoralis minor muscle.

Understanding these levels is critical for accurate reporting and communication with surgeons and oncologists regarding the extent of nodal involvement.

Fig. 1. Axillary Lymph Node Levels and Anatomy

Diagram illustrating the anatomical boundaries of the axilla and the three levels of axillary lymph nodes (Level I, Level II, Level III) in relation to the pectoralis minor muscle and surrounding structures. Key anatomical landmarks such as the axillary artery, vein, and brachial plexus are also depicted.

Mastering Axillary Imaging Techniques and Interventions

Standard imaging protocols for evaluating palpable axillary lumps in women over 30 typically begin with diagnostic mammography, incorporating a skin marker to pinpoint the palpable area, followed by targeted ultrasound. However, imaging algorithms may vary geographically; for instance, in the UK, mammographic evaluation often commences at age 40. In younger patients, ultrasound is often the primary initial imaging modality.

For patients presenting with a focal axillary lump, targeted scanning over the area of concern is the initial step. However, if suspicious findings are identified, comprehensive imaging of the entire axillary region is crucial to assess for any associated abnormalities. In patients newly diagnosed with breast cancer, axillary imaging should be even more extensive, encompassing the entirety of the axillary contents to accurately stage nodal involvement.

Examination of Level I lymph nodes necessitates visualizing the axillary vessels and thoroughly scanning the fatty tissue from the anteromedial border of the pectoralis muscles to the posterolateral margins of the latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles. The lateral thoracic and thoracodorsal arteries, along with their smaller branches, serve as valuable anatomical landmarks during scanning. While lymph node groups often follow these vessels, isolated nodes within the axillary fat are also frequently encountered. Crucially, the inferior axillary tail region must be carefully evaluated, as abnormal nodes are commonly found in this location. Levels II and III are not routinely scanned unless enlarged Level II nodes are suspected.

Axillary ultrasound should be performed utilizing a high-frequency (7.5–17 MHz) linear-array transducer to optimize image resolution and detail. In patients with larger body habitus or a substantial axillary fat pad, a lower frequency (5–7.5 MHz) transducer may be necessary, albeit with a potential compromise in spatial resolution. The patient should be positioned in a supine oblique position with the ipsilateral arm abducted and externally rotated (“bathing beauty” position) to maximize axillary exposure and visualization. All findings must be meticulously documented in orthogonal planes, with and without caliper measurements, and the lesion’s largest dimension should be recorded.

Many facilities incorporate grayscale, color Doppler, or power Doppler ultrasound to enhance lymph node characterization. Color Doppler, in particular, is valuable for assessing nodal vascularity, requiring low wall filter and velocity settings (high pulse repetition frequency) to detect subtle abnormal blood flow. The color gain should be adjusted to a level that detects subtle flow without introducing color noise artifact. Ultrasound demonstrates high sensitivity (94%) and moderate specificity (72%) in differentiating suspicious from benign lymph nodes based on size and morphological features.

When initial axillary imaging reveals suspicious findings, percutaneous procedures such as ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or core needle biopsy are often indicated. FNA is frequently the preferred initial approach due to its diagnostic efficacy and minimal complication risk (bleeding, infection, non-diagnostic sample). FNA typically employs 22–25 gauge needles, with aspirates sent for cytological analysis. Multiple passes (at least three) are generally performed, particularly if an on-site cytologist is not available. If lymphoma is a clinical concern, additional aspirates should be obtained for flow cytometry. However, FNA has limitations, including operator dependence, reliance on cytology expertise, and a reported false-negative rate of 12–23%. Confirmation of metastatic involvement via FNA in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer often dictates proceeding directly to axillary lymph node dissection, precluding sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Core needle biopsy, utilizing 12–18 gauge spring-loaded or vacuum-assisted devices, offers an alternative percutaneous diagnostic approach. Axillary core biopsy carries similar risks to other image-guided procedures, primarily bleeding and infection. Given the presence of axillary vessels and nerves, a “no-throw” technique is preferred to minimize hematoma risk and nerve damage. While core biopsy may yield a benign diagnosis, the upgrade rate to malignancy on surgical excision varies widely (0–36%) in literature, potentially due to small cohort sizes and sampling error.

Axillary Lump Differential Diagnosis: A Spectrum of Possibilities

The axilla can harbor a diverse range of pathological processes, manifesting as various imaging findings. From superficial skin lesions to deep posterior chest wall masses, a comprehensive differential diagnosis requires astute anatomical knowledge and clinical correlation. Axillary findings can be broadly categorized into: skin lesions, congenital and developmental anomalies, infectious, inflammatory, and metastatic lymphadenopathy, post-operative changes, benign neoplasms, and extra-axillary masses (Table 1).

Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of Axillary Findings: Benign vs. Malignant Considerations

| Category | Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|---|

| Skin & Subcutaneous Tissues | Seborrheic keratosis, sebaceous cyst, epidermoid inclusion cyst | Skin metastases, melanoma |

| Accessory Breast Tissue | Fibroadenoma, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), fibrocystic change | Breast cancer |

| Lymph Node Enlargement | Hyperplasia/reactive node, HIV/immunocompromised state, granulomatous disease (sarcoidosis), lymphoma/leukemia, Castleman’s disease | Primary breast malignancy, metastatic disease (breast, lung, ovarian, gastric, melanoma) |

| Lymph Node Calcifications/Punctate Densities | Granulomatous disease, gold therapy (rheumatoid arthritis treatment) | Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), metastatic disease [thyroid (papillary), ovarian] |

| Post-operative Findings | Skin thickening, lymphedema, post-operative fluid collections/lymphocele, fat necrosis, abscess, hematoma | Primary or metastatic recurrence |

| Neoplasms | Granular cell tumor, schwannoma | Primary breast cancer |

Skin Lesions and Glands: Superficial Axillary Findings

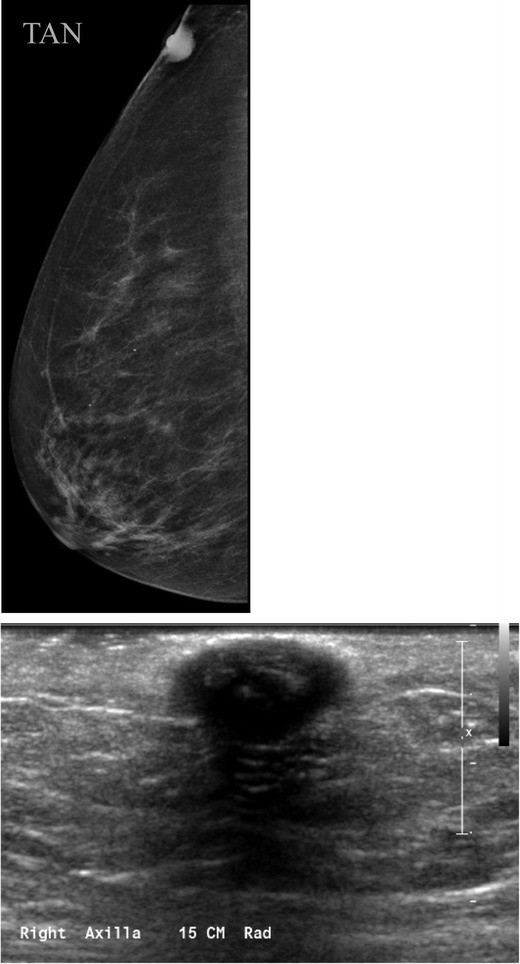

Seborrheic keratosis, a common benign skin lesion, presents as a raised, verrucoid growth. Epidermal inclusion cysts and sebaceous cysts (Fig. 2), located at the dermal-subcutaneous fat junction, appear as circumscribed masses, often exhibiting a visible tract to the skin surface. Epidermal inclusion cysts are prevalent in the axilla and inframammary fold. Antiperspirant artifact can also mimic pathology on mammography, appearing as radiopaque densities overlying the axilla (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Sebaceous Cyst of the Axilla

a) Tangential mammographic view demonstrating a skin lesion in the axilla. b) Ultrasound image confirming a hypoechoic mass located within the skin, consistent with a sebaceous cyst or epidermal inclusion cyst.

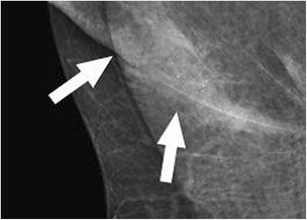

Fig. 3. Antiperspirant Artifact Mimicking Axillary Pathology

Magnified mammographic view of the axilla demonstrating radiopaque densities superficial to the skin surface, indicative of antiperspirant artifact.

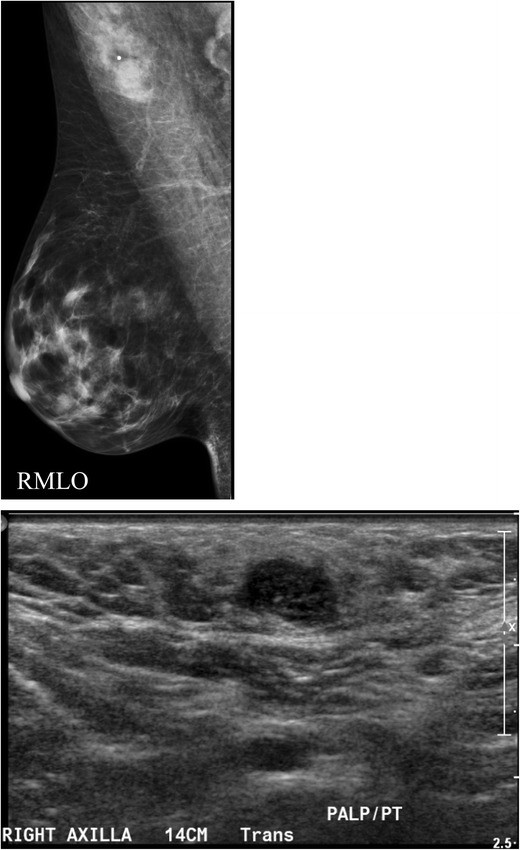

Congenital Anomalies: Accessory Breast Tissue in the Axilla

Breast tissue development originates from mammary ridges extending along the ventral embryo surface. Typically, the milk line regresses, except for the upper third mammary ridge, which forms the breast. Incomplete involution of the milk line results in accessory breast tissue, most frequently in the axilla, but it can occur anywhere along the milk line. Accessory breast tissue occurs in 2–6% of women (Fig. 4) and can be visualized on mammography, ultrasound, and MRI. Both benign and malignant breast lesions, such as cysts, fibroadenomas, PASH, and breast cancer, can arise within accessory breast tissue.

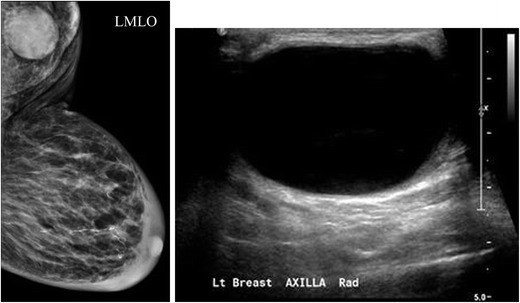

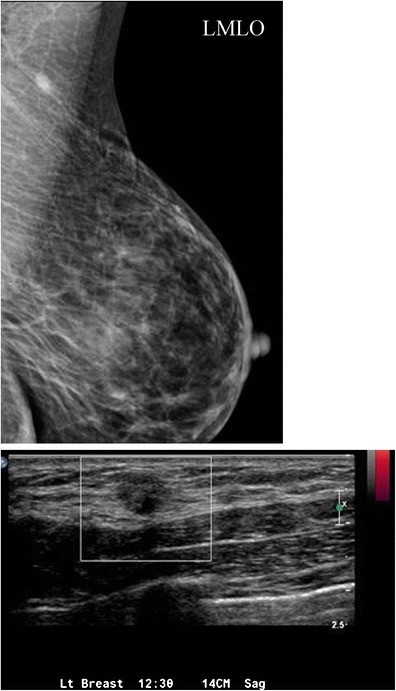

Fig. 4. Accessory Breast Tissue with Fibroadenoma

a) Mammographic MLO view with a skin marker (BB) placed over the palpable axillary area, showing heterogeneously dense asymmetry consistent with breast tissue. b) Targeted axillary ultrasound revealing fibroglandular breast tissue and a hypoechoic solid mass, subsequently biopsied and diagnosed as a fibroadenoma within accessory breast tissue.

Lymph Node Pathology: Differentiating Benign from Malignant Axillary Lymphadenopathy

While mammography can partially image the axilla, ultrasound is the optimal modality for detailed axillary lymph node assessment. Benign axillary lymph nodes typically measure less than 2 cm and exhibit a hilar radiolucent notch on mammography. Increased size or density raises suspicion. Normal benign-appearing lymph nodes on ultrasound are oval or lobulated with smooth, well-defined margins. The cortex is uniformly thin (≤ 3 mm) and slightly hypoechoic (Fig. 5), while the echogenic hilum constitutes the majority of the node volume. Nodes meeting these criteria have a high negative predictive value for excluding metastases. Arterial flow within the hilum can be demonstrated with Doppler imaging.

Morphological criteria, such as cortical thickening, hilar effacement, and non-hilar cortical blood flow, are more sensitive indicators of malignancy than size alone. Suspicious features include a round shape, absent fatty hilum, and increased cortical thickness (> 3 mm), either concentric or focal (Fig. 6).

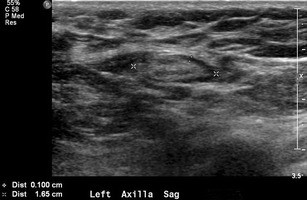

Fig. 5. Normal Axillary Lymph Node Ultrasound Appearance

Ultrasound image of a normal axillary lymph node displaying typical benign features: a smooth, gently lobulated oval shape, a uniformly thin hypoechoic cortex (less than 3mm), and a prominent central echogenic hilum.

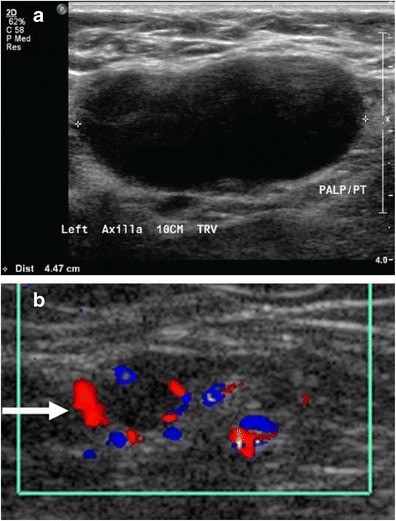

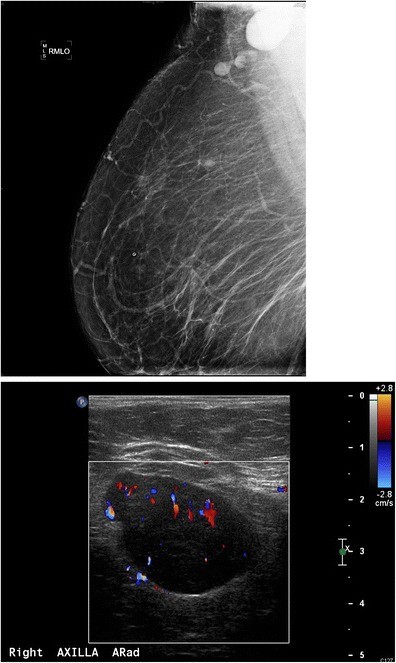

Fig. 6. Malignant Axillary Lymph Node Ultrasound Features

Ultrasound images demonstrating malignant lymph node characteristics: a) Absence of the fatty hilum and b) Focal cortical thickening exceeding 3mm with hypervascularity demonstrated by color Doppler ultrasound, showing abnormal (non-hilar cortical) blood flow and hyperemic hilar flow.

A focal cortical bulge or thickening (Fig. 7) can be an early sign of metastasis but is non-specific. A true abnormal bulge is a focal cortical thickening that does not conform to the hilum margin, is distinctly hypoechoic, and is more concerning when associated with cortical blood flow. Diffuse cortical thickening is even less specific and more often associated with reactive nodes. Eccentric cortical thickening is more suspicious than diffuse thickening, but both warrant further investigation. Advanced nodal involvement may manifest as hilar effacement or a rounded hypoechoic mass. Replacement of the node by an ill-defined mass is highly suspicious for malignancy. Nodal microcalcifications may also be seen (Fig. 7), raising concern for specific malignancies.

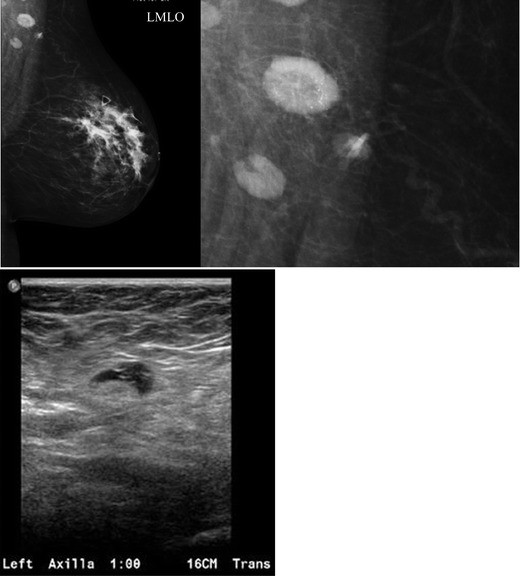

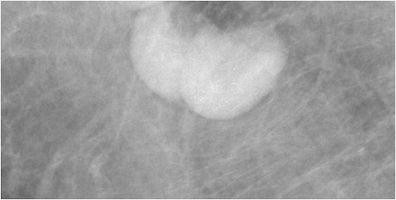

Fig. 7. Metastatic Lymph Node with Cortical Thickening and Calcifications

a) Mammographic MLO view with magnified axillary image showing a lymph node with eccentric cortical thickening and cortical calcifications. b) Corresponding ultrasound confirming echogenic foci within the thickened cortex, suspicious for malignancy, in a patient with metastatic carcinoma confirmed by FNA.

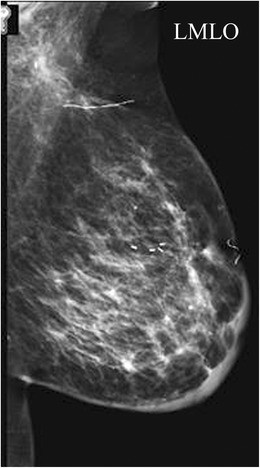

Fig. 8. Reactive Axillary Lymph Node with Focal Cortical Thickening

a) Mammographic MLO view demonstrating a focally thickened, non-enlarged axillary lymph node. b) Ultrasound confirming a lymph node with focal cortical thickening and c) internal vascular flow, ultimately diagnosed as a reactive lymph node after FNA.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) has shown promise in visualizing abnormal nodes post-microbubble injection, potentially aiding sentinel lymph node identification and biopsy.

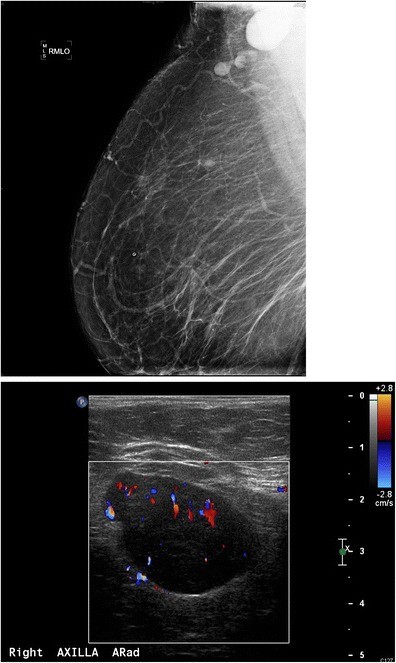

Enlarged axillary lymph nodes may be associated with benign (Figs. 8, 9) or neoplastic processes (Figs. 6, 7). The differential diagnosis of enlarged axillary lymph nodes includes reactive hyperplasia, HIV/immunocompromised states, sarcoidosis and other granulomatous diseases, lymphoma/leukemia, and metastatic disease (breast, lung, ovarian, gastric, melanoma). Calcifications within axillary lymph nodes can be benign or malignant, with differentials including prior granulomatous infection, gold therapy (Fig. 10) for rheumatoid arthritis, collagen vascular disease, and metastasis from breast, thyroid, or ovarian cancer. Distinguishing nodal calcifications from superficial antiperspirant artifact is crucial and can be achieved by repeat mammography after axillary cleansing.

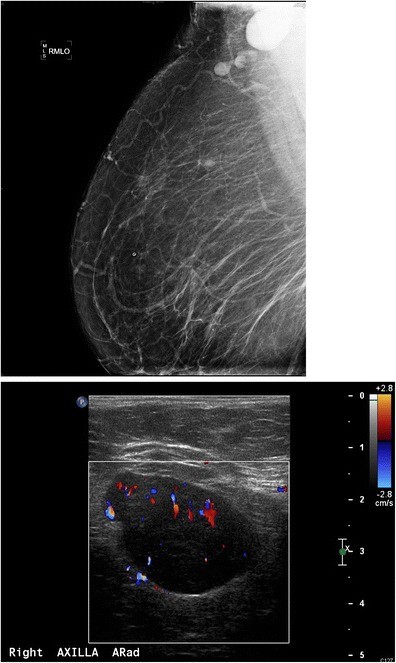

Fig. 9. Sarcoidosis Presenting as Enlarged Axillary Lymph Node

a) Mammographic MLO views showing a dense, enlarged right axillary lymph node. b) Ultrasound confirming a large, fatty-replaced lymph node with non-hilar internal vascular flow. Biopsy revealed sarcoidosis, demonstrating a benign cause of enlarged axillary lymphadenopathy.

Fig. 10. Lymph Node Calcifications Secondary to Gold Therapy

Magnified mammographic view of axillary lymph nodes displaying fine punctate radiopaque densities, characteristic of gold deposition in a patient undergoing gold therapy for rheumatoid arthritis.

Post-operative Axillary Changes: Expected and Concerning Findings

Post-axillary surgery, a spectrum of imaging findings can be observed. Common post-operative changes include skin and trabecular thickening (Fig. 11), post-operative fluid collections or lymphoceles (Fig. 12), fat necrosis, and recurrence.

Fig. 11. Post-operative Skin and Trabecular Thickening

Mammographic view demonstrating diffuse skin and trabecular thickening in the breast and axilla, consistent with expected post-treatment changes following lumpectomy, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and radiation therapy for breast cancer.

Fig. 12. Post-operative Lymphocele of the Axilla

a) Mammographic MLO view and b) Ultrasound of the axilla revealing a well-circumscribed, predominantly anechoic cystic structure with internal debris, consistent with a post-operative lymphocele, in a patient with prior axillary surgery.

Benign Neoplasms of the Axilla: Rare Mimics of Malignancy

Several rare benign neoplasms can occur in the axilla, sometimes mimicking breast cancer in the axillary tail of Spence. These tumors, often neural in origin, are frequently asymptomatic and incidentally detected on screening mammography. Percutaneous biopsy is usually sufficient to confirm benignity, often obviating surgical excision.

Granular Cell Tumor (GCT)

GCT, a rare neural neoplasm, accounts for less than 1% of breast lesions and is more common in African American women. Clinically, GCTs present as firm, palpable masses, typically 1-2 cm in size. Mammographically, GCTs can mimic carcinoma, exhibiting irregular or spiculated margins. Ultrasound may show a solid hypoechoic mass with irregular margins (Fig. 13). While usually benign, malignant GCTs exist, characterized by larger size (>4 cm), high mitotic rate, rapid growth, and local invasion. Diagnosis is confirmed by immunohistochemical staining for S-100 protein. Treatment is typically wide surgical excision.

Fig. 13. Granular Cell Tumor of the Axilla on Mammography and Ultrasound

a) Mammographic MLO view demonstrating an irregular asymmetry in the axillary region. b) Ultrasound revealing an irregular hypoechoic, hypovascular mass in the axilla, diagnosed as a granular cell tumor via ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy.

Schwannoma

Schwannomas, originating from Schwann cells of the peripheral nerve sheath, are rarely found in the breast. Mammographically, they often appear as well-defined round or oval masses, but can be ill-defined (Fig. 14). Ultrasound findings are variable, but often depict a solid hypoechoic, well-defined mass with posterior acoustic enhancement. Diagnosis often requires surgical excision to differentiate from other spindle cell lesions, although core needle biopsy with S-100 protein immunostaining can suggest schwannoma.

Fig. 14. Schwannoma of the Axilla – Mammographic Appearance

Mammographic MLO view showing a well-defined ovoid mass in the upper outer quadrant of the breast/axillary region, diagnosed as a schwannoma in an asymptomatic screening patient.

Extra-axillary Lesions: Beyond the Confines of the Axilla

The axilla encompasses muscles and bones of the shoulder and upper rib cage. Recognizing that an axillary mass may originate from these extra-axillary structures is crucial for accurate differential diagnosis. While rare, benign and malignant muscular neoplasms can occur. Intramuscular myxoma, a benign neoplasm of fibroblasts, can present as a complex axillary mass (Fig. 15). Imaging typically shows a complex mass on ultrasound and heterogeneous signal on MRI. Biopsy is essential to differentiate intramuscular myxoma from myxoid liposarcoma.

Fig. 15. Intramuscular Myxoma of the Latissimus Dorsi Muscle

a) Mammography showing no focal abnormality. b) Ultrasound demonstrating a complex oval mass with cystic and solid components within muscle. c, d) Axial STIR and post-gadolinium MRI sequences confirming an intramuscular lesion with characteristic signal intensity and enhancement patterns, diagnosed as intramuscular myxoma of the latissimus dorsi muscle via CT-guided biopsy.

Conclusion: Integrating Imaging for Axillary Lump Diagnosis and Management

A comprehensive understanding of normal axillary anatomy is fundamental to accurately interpret imaging findings and determine the etiology of axillary masses. The differential diagnosis of an axillary lump is broad, encompassing a wide spectrum of benign and malignant conditions, from skin lesions and infections to lymphadenopathy, accessory breast tissue, neoplasms, and extra-axillary masses. Imaging, primarily mammography and targeted ultrasound, is indispensable for evaluating axillary pathology. When indicated, FNA or core needle biopsies are safe and effective procedures for establishing a definitive diagnosis and guiding appropriate patient management strategies for axillary masses. Integrating clinical presentation, anatomical knowledge, and meticulous imaging analysis is paramount for optimal patient care in the setting of axillary concerns.

Contributor Information

V. Dialani, Phone: 617-667-5681, Email: [email protected]

D. F. James, Phone: 617-510-9432, Email: [email protected]

P. J. Slanetz, Phone: 617-667-2547, Email: [email protected]