Back pain stands as a ubiquitous health concern, frequently prompting individuals to seek medical attention, particularly in emergency settings. Its persistent nature can lead to significant disability, affecting individuals across all age groups. While mechanical or nonspecific causes are prevalent, the underlying etiologies vary with age, necessitating a nuanced approach to diagnosis and treatment.

This article delves into the complexities of back pain, aiming to equip healthcare professionals with the knowledge to discern its diverse origins, identify critical warning signs indicative of serious conditions, and formulate a robust, interprofessional diagnostic and therapeutic strategy. Emphasis will be placed on evidence-based conservative management for nonspecific back pain, prioritizing physical activity over extensive pharmacological interventions. This guide serves to enhance clinical competence, improve patient outcomes, and mitigate the substantial impact of back pain on patients’ lives, productivity, and healthcare expenditure.

Objectives:

- To delineate the broad spectrum of etiologies contributing to back pain.

- To recognize and interpret red flag symptoms in back pain patients, facilitating prompt identification of severe conditions like malignancy or cauda equina syndrome.

- To enumerate and describe the comprehensive range of management options for back pain.

- To foster the development of interprofessional team strategies aimed at enhancing care coordination and communication in the evaluation and management of back pain patients.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

Back pain is a leading cause for consultations in primary and emergency care settings, placing a significant economic burden on healthcare systems. Annual expenditures for back pain management are estimated at $200 billion, encompassing direct medical costs and indirect costs related to lost work hours, reduced productivity, and workers’ compensation claims.[1]

The origins of back pain are diverse, spanning a wide array of conditions in both adults and children. However, the majority of cases are attributed to mechanical issues or nonspecific factors. Mechanical back pain constitutes approximately 90% of all cases, potentially leading clinicians to overlook less common but serious underlying causes.[2][3]

Effective back pain management hinges on the ability to identify red flags and determine the most appropriate course of treatment. While most cases can be effectively managed with conservative approaches, the presence of nerve dysfunction or other alarming symptoms necessitates thorough investigation and a multidisciplinary approach.[4]

Treatment modalities range from pharmacological interventions, targeting pain pathways and muscle relaxation,[5] to various physical therapy techniques for nonpharmacological management and injury recovery.[6] Alternative therapies like acupuncture have shown moderate benefit in alleviating back pain. Surgical intervention is typically reserved for cases involving severe nerve dysfunction or serious underlying pathologies such as malignancy.[7][8] For back pain persisting beyond six weeks post-acute injury, imaging studies including radiography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are warranted.

A comprehensive evaluation is crucial for accurately diagnosing the cause of back pain and developing a personalized treatment plan. Addressing the root cause of back pain is essential for improving patients’ functional capacity and overall quality of life.

Etiology

Back pain can stem from a multitude of conditions, broadly categorized as follows:[9]

- Traumatic: Direct or indirect force can result in back pain, including whiplash injuries, strains, and traumatic fractures.

- Degenerative: Age-related wear and tear, overuse, or pre-existing conditions can weaken musculoskeletal structures, leading to conditions like intervertebral disk herniation and degenerative disk disease.

- Oncologic: Primary or secondary malignant lesions can develop within the back’s anatomical structures, potentially causing pathologic fractures of the axial skeleton.

- Infectious: Infections of the musculoskeletal structures can arise from direct inoculation or spread from other sites.

- Inflammatory: Non-infectious, non-malignant inflammatory conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis and sacroiliitis can cause back pain, potentially leading to spinal arthritis in chronic cases.

- Metabolic: Disruptions in calcium and bone metabolism, as seen in osteoporosis and osteosclerosis, can manifest as back pain.

- Referred Pain: Inflammation or pathology in visceral organs, such as biliary colic, lung disease, or aortic/vertebral artery issues, can be referred to the back.

- Postural: Prolonged upright postures, pregnancy, and certain occupations can predispose individuals to postural back pain.

- Congenital: Inborn conditions affecting the axial skeleton, like kyphoscoliosis and tethered spinal cord, can be causative.

- Psychiatric: Back pain can be a symptom in patients with chronic pain syndromes and mental health conditions. Malingering should also be considered.

The chronicity of back pain is also a crucial factor in differential diagnosis. Acute back pain often has different origins than chronic back pain. A thorough clinical assessment and appropriate diagnostic investigations are usually sufficient to pinpoint the exact cause. Depending on the findings, referrals to specialists such as orthopedic surgeons, neurologists, rheumatologists, or pain management specialists may be indicated for further evaluation and tailored treatment strategies.

Epidemiology

Back pain is a pervasive issue among adults globally. Studies indicate that up to 23% of adults worldwide experience chronic low back pain, with recurrence rates ranging from 24% to 80% within a year.[10][[11]](#article-18089.r11] The lifetime prevalence of back pain in adults is remarkably high, reaching up to 84%.[12]

In pediatric populations, back pain is less common than in adults. A Scandinavian study reported point prevalences of approximately 1% in 12-year-olds and 5% in 15-year-olds. By age 18 for girls and 20 for boys, half would have experienced at least one episode of back pain.[13] The lifetime prevalence in adolescents steadily increases with age, approaching adult levels by age 18.[14]

History and Physical Examination

The diagnostic process for back pain commences with a detailed history and physical examination. Establishing the pain’s onset is paramount. Acute back pain, lasting less than 6 weeks, is often linked to trauma or sudden exacerbations of chronic conditions like malignancy. Chronic back pain, persisting beyond 12 weeks, may be mechanical in origin or related to long-standing underlying conditions.

Identifying factors that provoke or alleviate the pain is crucial. This information not only provides diagnostic clues but also guides clinicians in tailoring appropriate pain management strategies.

The quality of pain can aid in differentiating between visceral and non-visceral sources. Well-localized pain often suggests an organic etiology. Associated symptoms provide further insights into the potential source of back pain.

Relevant information can be gleaned from the patient’s medical, family, occupational, and social history. For instance, a history of cancer chemotherapy raises suspicion of metastasis or secondary tumors. Certain autoimmune arthritides have hereditary components. Exposure to tuberculosis in endemic regions may suggest Pott disease or spinal tuberculosis. Prolonged sitting during work can contribute to both acute and chronic back pain.

A focused physical examination should encompass inspection, auscultation, palpation, and provocative maneuvers. Visual inspection may reveal deformities, signs of inflammation, or skin lesions, but often does not pinpoint the underlying cause. Auscultation is valuable when pulmonary pathology is suspected. Palpation can elicit localized musculoskeletal tenderness.

Provocative exercises can provide diagnostic insights. The straight-leg-raising (SLR) test is useful for diagnosing lumbar disk herniation. Performed by raising the patient’s leg between 30° and 70°, a positive result is indicated by ipsilateral leg pain developing at less than 60°. The crossed SLR test, raising the leg contralateral to the herniation side, is even more specific.[15][16]

The Stork test assesses for spondylolysis. The examiner supports the patient while they stand on one leg and hyperextend the back, repeated on both sides. Pain during hyperextension indicates a positive result.

The Adam test aids in scoliosis evaluation. The patient bends forward with feet together, arms extended, and palms together. A thoracic hump may be visible in patients with scoliosis.[17]

Assessing range of motion, limb strength, deep tendon reflexes, and sensation evaluates the integrity of both musculoskeletal and neurological systems.

Red flags identified during history or physical examination necessitate imaging and further diagnostic testing. These warning signs are categorized for adults and pediatric patients:

- Malignancy:

- History: Previous metastatic cancer, unexplained weight loss.

- Physical Exam: Focal tenderness with risk factors.

- Infection:

- History: Recent spinal procedure (within 12 months), intravenous drug use, immunosuppression, prior lumbar spine surgery.

- Physical Exam: Fever, spinal wound, localized pain, tenderness.

- Fracture:

- History: Significant trauma (age-related), prolonged corticosteroid use, osteoporosis, age > 70 years.

- Physical Exam: Contusions, abrasions, spinous process tenderness.

- Neurologic:

- History: Progressive motor/sensory loss, new urinary retention/incontinence, new fecal incontinence.

- Physical Exam: Saddle anesthesia, anal sphincter atony, significant motor deficits in multiple myotomes.

Red Flags in Pediatric Patients:[20][21]

- Malignancy:

- History: Age < 4 years, nighttime pain.

- Physical Exam: Focal tenderness with risk factors.

- Infectious:

- History: Age < 4 years, nighttime pain, tuberculosis exposure history.

- Physical Exam: Fever, spinal wound, localized pain, tenderness.

- Inflammatory:

- History: Age < 4 years, morning stiffness > 30 minutes, improvement with activity/hot showers.

- Physical Exam: Limited range of motion, localized pain, tenderness.

- Fracture:

- History: Activities with repetitive lumbar hyperextension (sports like cheerleading, gymnastics, wrestling, football).

- Physical Exam: Spinous process tenderness, positive Stork test.

Evaluation

History and physical examination often suffice to determine the cause of back pain. Early imaging in adults is associated with poorer outcomes due to increased invasive interventions with limited benefit.[22][23] This principle extends to pediatric populations. However, concerning signs warrant diagnostic testing. In adults, back pain persisting beyond 6 weeks despite conservative management also necessitates imaging. In children, imaging is recommended for continuous pain lasting over 4 weeks.[91]

Plain anteroposterior and lateral (APL) radiographs can detect bone pathologies (see Image. Multiple Myeloma Involving the Spine). MRI is indicated for soft tissue lesions, including nerves, intervertebral disks, and tendons. Both modalities can reveal malignancy and inflammation, but MRI is superior for soft tissue involvement.[24][25] Bone scans can detect osteomyelitis, diskitis, and stress reactions but are less sensitive than MRI for these conditions.[26]

Adolescents with MRI evidence of disk herniation may require a CT scan to rule out apophyseal ring separation, occurring in approximately 5.7% of cases.[27]

Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies are indicated for patients with prior spinal surgery experiencing radiculopathy or plexopathy. Image-guided diagnostic injections can confirm sacroiliac joint injury.[92]

Laboratory tests may be necessary in certain back pain cases. Rheumatologic assays like HLA-B27, antinuclear antibody (ANA), rheumatoid factor (RF), and Lyme antibodies are generally nonspecific for back pain and less helpful.[28][29] However, inflammatory markers C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) can be useful.[30] A complete blood count (CBC) and blood cultures can aid in diagnosing inflammatory, infectious, or malignant etiologies. Elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and uric acid levels can be associated with rapid marrow turnover conditions like leukemia.[31]

Treatment / Management

Management strategies for back pain differ between adults and children. While many cases are nonspecific, degenerative disease and musculoskeletal injury are more common in adults, whereas overuse and muscle strain are more frequent in children and adolescents. Rare causes like malignancy and metabolic conditions also present differently across age groups. Therefore, treatment must be tailored to both the condition and patient age.

Management of Back Pain in Adults

For acute back pain in adults, serious underlying conditions must be ruled out initially. In the absence of red flags, reassurance and symptomatic relief are paramount. First-line treatments are nonpharmacological and include:[93]

- Early return to normal activities, avoiding heavy labor.

- Activity modification to avoid pain-provoking movements.

- Patient education regarding back pain management and self-care strategies.

Second-line options may include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants, opioids, spinal manipulation, physical therapy, superficial heat application, and alternative therapies like acupuncture and massage. Patient education must be personalized to address individual circumstances and is crucial for preventing pain exacerbation or recurrence. Follow-up within 2 weeks is recommended. Resumption of normal activities should be encouraged upon symptom resolution.

For acute radicular back pain in adults, NSAIDs, exercise, traction, and spinal manipulation may be considered. Diazepam and systemic steroids have not demonstrated added benefit.

Diagnostic testing is necessary if serious conditions cannot be excluded. Referral to specialists for further evaluation and treatment should be considered as needed.

Chronic back pain management follows a similar approach. Ruling out serious conditions is the initial step. For nonspecific chronic back pain, maintaining activity and avoiding aggravating factors are key. Exercise therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy are considered first-line treatments.[32][[33]](#article-18089.r33] Second-line treatments encompass spinal manipulation, massage, acupuncture, yoga, stress reduction techniques, NSAIDs, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and interdisciplinary rehabilitation.[34][35][36]

The efficacy of anticonvulsants like gabapentin and topiramate in managing back pain remains uncertain.[37][[38]](#article-18089.r38] Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has not shown superior efficacy to placebo in chronic back pain management.[39]

Surgical referral is generally reserved for patients with disabling low back pain persisting for over a year, as recommended by the American Pain Society.[40] However, evidence regarding the effectiveness of common invasive procedures like epidural space injections and lumbar disk replacement is mixed.[41][42]

Management of Back Pain in Children and Adolescents

Pediatric back pain treatments are less extensively studied. Activity modification, physical therapy, and NSAIDs are widely supported as first-line therapies. If serious pathology is identified, treatment should adhere to the standard of care for that condition. Spondylolysis from repetitive spinal stress can be managed conservatively, similar to adults. However, young athletes may require surgical intervention in some cases.[43][44] Symptoms persisting beyond 6 months of conservative therapy or Grade III or IV spondylolisthesis may warrant referral to a pediatric spine surgeon.[45][46]

Scheuermann’s kyphosis with spinal curvature less than 60° can be managed conservatively with physical therapy and guided exercise. Bracing may be added for curvatures between 60° and 70°. Surgical correction is indicated for curvatures exceeding 75°, especially if conservative measures fail and skeletal maturity is reached.[47][48] Surgical referral is also indicated for spinal curvature of 20° or greater during peak growth, significant scoliosis, progressive curvature, and atypical scoliosis.[49]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of back pain is broad, encompassing various conditions in both adults and children. The following list, while not exhaustive, includes common and serious conditions presenting with back pain, along with associated symptoms and physical examination findings.

Differential Diagnosis of Back Pain in Adults

- Lumbosacral muscle strains and sprains: Typically due to trauma or overuse; pain worsens with movement, improves with rest; restricted range of motion; muscle tenderness.

- Lumbar spondylosis: Common in patients > 40 years; possible hip pain; pain with lower limb extension/rotation; usually normal neurological exam.

- Disk herniation: Commonly L4-S1 segments; possible paresthesia, sensory changes, weakness, reflex changes depending on nerve root involvement.

- Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: Repetitive spinal stress; back pain radiating to gluteal area and posterior thighs; L5 distribution neurologic deficits.[50]

- Vertebral compression fracture: Localized back pain worsening with flexion; point tenderness; acute or chronic; risk factors: steroid use, vitamin D deficiency, osteoporosis.

- Spinal stenosis: Leg sensory/motor weakness relieved by rest (neurogenic claudication); neurological exam may be initially normal, progressing with stenosis.

- Tumor: Possible unexplained weight loss, focal tenderness, malignancy risk factors (97% spinal tumors are metastatic).[51]

- Infection: History of recent spinal surgery, IV drug use, immunosuppression; fever, spinal wound, localized pain, tenderness; common: vertebral osteomyelitis, diskitis, septic sacroiliitis, epidural/paraspinal abscess; consider tuberculosis in patients from endemic regions.[52]

- Fracture: Trauma, prolonged corticosteroid use, osteoporosis; common in patients > 70 years; contusions, abrasions, spinous process tenderness.

Differential Diagnosis of Back Pain in Children and Adolescents

- Tumor: Fever, malaise, weight loss, nighttime pain, new onset scoliosis; osteoid osteoma most common, pain relieved by NSAIDs.[53][54][55]

- Infection: Fever, malaise, weight loss, nighttime pain, new onset scoliosis; refusal to walk; common: vertebral osteomyelitis, diskitis, septic sacroiliitis, epidural/paraspinal abscess; consider epidural abscess with radicular pain/neurologic deficits.[56][57]

- Disk herniation and slipped apophysis: Acute back pain, radicular pain, new onset scoliosis; positive SLR, pain on spinal flexion.

- Spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and posterior arch lesion: Acute onset back pain with radicular pain; hamstring tightness; positive SLR, pain on spinal extension.

- Vertebral fracture: Trauma most common cause; acute back pain with other injuries; possible neurological deficits; stress fractures may be insidious with postural changes.

- Muscle strain: Acute back pain, muscle tenderness without radiation.

- Scheuermann’s kyphosis: Chronic back pain, rigid kyphosis.

- Inflammatory spondyloarthropathies: Chronic pain, morning stiffness > 30 minutes, sacroiliac joint tenderness.

- Psychological disorder (conversion/somatization): Persistent subjective pain, normal physical findings.

- Idiopathic scoliosis: Usually asymptomatic, positive Adam test; back pain may have another cause.[58]

Prognosis

The prognosis of back pain in adults is variable and etiology-dependent. Most nonspecific cases resolve without lasting complications. Conservative therapy and patient education are often effective, highlighting the subjective and stress-related components of pain. Factors associated with chronic, disabling back pain include prior episodes, symptom intensity, depression, fear-avoidance behavior, and leg or widespread symptoms in cases with unidentifiable causes.[59]

Social factors significantly influence prognosis.[[60]](#article-18089.r60] Lower educational attainment, laborious jobs, poor compensation, and job dissatisfaction correlate with worse outcomes and higher disability rates.[61][62] Lifestyle factors, such as BMI > 25 and smoking, are also associated with persistent back pain.[63].

Pediatric back pain prognosis is less studied but also influenced by etiology.[64] Back pain from cancer is more likely to cause disability than muscle strain.[65] Nonspecific back pain in younger individuals can be worsened by behavioral comorbidities.[66] Conduct problems, ADHD, passive coping, and fear-avoidance behavior are associated with negative impacts on back pain outcomes.[67][68]

Complications

Complications of back pain are determined by the underlying etiology and can have both physical and social consequences. Physical complications include chronic pain, deformity, and neurologic deficits. Social complications include disability, reduced GDP, and increased absenteeism. Back pain is the leading global cause of disability, accounting for 60.1 million years of disability worldwide in 2015.[69] In the US, low back pain is the most common cause of disability.[70]

Early intervention and prevention of chronicity are crucial to mitigate complications. Early ambulation improves outcomes, while sedentary behavior and obesity worsen prognosis.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Rehabilitation strategies are tailored to the underlying cause, patient comorbidities, and health goals. The McKenzie method is often beneficial for chronic nonspecific low back pain.[71] Clinical Practice Guidelines for Physical Therapy recommend manual therapy, trunk strengthening, centralization, directional preference exercises, and progressive endurance exercises.[72] Occupational therapy can assist with activities of daily living and adaptive equipment. Assistive devices during patient transfers can reduce low back pain in healthcare workers.[73]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education for preventing back pain recurrence should be personalized. Individuals in non-labor-intensive jobs should maintain activity for healthy body weight, as BMI > 25 worsens outcomes. This also applies to those in labor-intensive jobs, who should additionally avoid heavy lifting and excessive back twisting. Lifting equipment should be used for heavy loads.

Smoking avoidance is crucial for all patients, as it increases back pain risk at any age.[74][75] Intensive patient education (2.5 hours) on activity modification, staying active, and early return to normal activity is effective in promoting return to work in adults.[76]

In children, the role of bookbag weight is debated, but the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends bookbags not exceed 10-20% of body weight.[77]

Most back pain is self-limited. However, patients should seek immediate medical attention for concerning signs like sudden sensory/motor weakness.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key practice points for back pain management:

Adults:

- Imaging is not routinely needed for acute low back pain without red flags.[[78]](#article-18089.r78]

- Initial treatment focuses on pain control and functional improvement.

- Acetaminophen is less effective than NSAIDs.[79][[80]](#article-18089.r80]

- Muscle relaxants offer short-term relief for acute low back pain, but sedation is a risk.[81]

- Antidepressants are not routinely recommended for acute low back pain.[82]

- Directional preference and centralization can guide physical therapy.[83][84][[85]](#article-18089.r85]

Children:

- Transient back pain with minor injury and no significant findings can be treated conservatively without further evaluation.

- Abnormal findings, constant pain, nighttime pain, or radicular pain warrant further evaluation.[86]

- Plain APL radiographs are recommended as initial imaging.

- Consider laboratory tests with clinical red flags. Thoracic malignancy and infection are more likely in children, especially < 4 years.[[87]](#article-18089.r87]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interprofessional collaboration is essential for comprehensive back pain care, improving outcomes and quality of life. The multidisciplinary team includes primary care providers, nurses, pharmacists, nutritionists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, radiologists, and specialists as needed.

Primary care providers initiate evaluation with history and physical examination, determine initial treatment, and assess need for further testing and referrals. They also educate patients and communicate follow-up plans, emphasizing smoking cessation and healthy weight.[88]

Nurses reinforce patient education and follow-up, provide evidence-based answers regarding nonpharmacologic therapy and activity, and ensure patient stability and care plan coordination before discharge.

Pharmacists educate patients on prescribed medications, benefits, risks, and proper intake, clarifying prescriptions with providers as needed.

Nutritionists assist obese patients in making healthier dietary choices for weight management. Obesity medicine specialists may prescribe adjunctive antiobesity medications.

Physical therapists prescribe strength and endurance exercises, effectively weaning patients from opioids.[[89]](#article-18089.r89] Occupational therapists provide ergonomic guidance and recommend assistive devices for home and work.

Radiologists interpret imaging findings and recommend further imaging if necessary.

Specialist referrals may include pain specialists for chronic pain management, rheumatologists for inflammatory conditions, neurosurgeons for severe radiculopathy or neurological changes, and mental health therapists for psychological components of back pain.[[90]](#article-18089.r90] Alternative medicine providers may also contribute to patient function improvement.

Effective interprofessional communication prevents duplicated tests and conflicting treatments, optimizing patient progress.

Review Questions

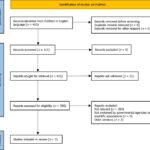

Figure

Alt Text: Lateral lumbar spine X-ray revealing lytic lesions in L1 and L4 vertebrae, indicative of Multiple Myeloma.

Multiple Myeloma Involving the Spine. This lateral lumbar spine x-ray shows lytic lesions in the L1 and L4 vertebral bodies. Contributed by Steve Lange, MD

References

[List of references from the original article – same as provided in the original]

Disclosure: Vincent Casiano declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Gurpreet Sarwan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Alexander Dydyk declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Matthew Varacallo declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.