Intimate partner violence (IPV) and its profound psychological impact on women have been recognized by the mental health community for decades. It is widely acknowledged that domestic violence is a form of gender-based violence, disproportionately affecting women through physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. While women may sometimes react or engage in mutual violence, they are far more likely to suffer physical and emotional harm. Alarmingly, women acting in self-defense are often arrested alongside their abusers.

Gender violence is deeply rooted in societal norms that socialize men to exert power over women. This socialization can lead some men to seek control and dominance through abuse. While the term “victim” may be considered controversial, it accurately describes the reality that battered women often need to regain control over their lives to become true survivors. Battered woman syndrome (BWS) is a set of psychological symptoms that can develop in women experiencing prolonged abuse, significantly hindering their ability to reclaim their autonomy. Mental health professionals play a crucial role in assisting these women through empowerment strategies, accurate Battered Woman Syndrome Diagnosis, and effective treatment approaches.

Battered Woman Syndrome as a Form of PTSD

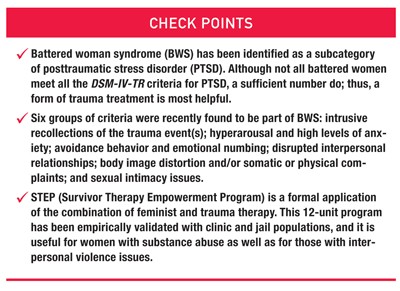

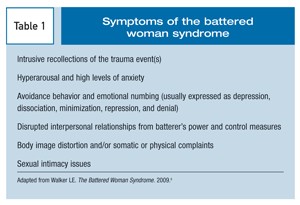

BWS is now recognized as a subcategory of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While not every woman experiencing battering meets all the diagnostic criteria for PTSD outlined in the DSM-IV-TR, a significant number do. Therefore, trauma-focused treatment modalities are highly beneficial in addressing BWS.

Table 1: Criteria Associated with Battered Woman Syndrome

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Intrusion Symptoms | Recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s); traumatic nightmares; flashbacks or other dissociative reactions in which the individual feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were recurring. |

| Avoidance Symptoms | Avoidance of trauma-related stimuli after the traumatic event(s). |

| Negative Alterations in Cognitions and Mood | Negative beliefs about oneself, others, or the world; trauma-related amnesia; persistent negative emotional state; feeling alienated from others; constricted affect. |

| Alterations in Arousal and Reactivity | Irritable behavior and angry outbursts; reckless or self-destructive behavior; hypervigilance; exaggerated startle response; problems with concentration; sleep disturbance. |

| Interpersonal Problems | Difficulties in relationships, isolation, distrust of others. |

| Learned Helplessness | A belief that one’s actions cannot affect outcomes, leading to passivity and acceptance of abuse. |

The Diagnostic Process for Battered Woman Syndrome

Accurate battered woman syndrome diagnosis is crucial for providing appropriate support and intervention. When interviewing a woman suspected of experiencing intimate partner violence, a structured approach is essential (See Table 2).

Table 2: Steps for Interviewing a Potentially Abused Woman

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Ensuring Safety | Begin the conversation privately, without the partner present. Develop a safety plan collaboratively. Be mindful that abusers often try to control the interview process, even when not physically present. Recognize that discussing separation is a particularly dangerous time for women in abusive relationships. |

| Validation | Validate the woman’s experience of abuse. Emphasize her strengths and the positive actions she has taken to protect herself and her children. Clearly communicate that no one deserves to be abused, regardless of their actions or words. Avoid victim-blaming questions that imply she provoked the abuser. |

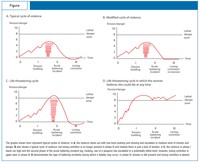

| Risk Assessment | Conduct a thorough risk assessment alongside a mental status examination. Many battered women experience co-occurring mental health conditions in addition to PTSD and BWS. Inquire about the history of abuse: the first incident, the worst incident, the most recent incident, and typical patterns of abuse to gauge the level of danger she faces. Utilize violence pattern analysis (See Figure) to assess lethality risk. |

| Treatment Plan | Collaboratively negotiate a treatment plan with the woman, such as the Survivor Therapy Empowerment Program (STEP). Assess her resilience alongside PTSD symptoms like re-experiencing, hypervigilance, arousal, and avoidance. While childhood history is relevant, prioritize addressing immediate safety and stabilization. |

Creating a Safe and Validating Environment

For a woman in an abusive relationship, safety is paramount. The period when separation is being considered or discussed is particularly perilous. Even after leaving the abuser, safety concerns may persist. It is crucial to foster a sense of safety and trust by assuring the woman that her vulnerability will not be exploited. Clinicians should establish clear boundaries by seeking permission before physical touch, note-taking, and discussing confidentiality and privilege. Initially, individual or group therapy is recommended over couples therapy in these situations.

Validation is a cornerstone of effective intervention. Battered women need to feel heard and believed when they recount their experiences of abuse. Highlighting their protective actions for themselves and their children reinforces their agency and strength. It is vital to explicitly state that abuse is never deserved, regardless of any perceived provocation. Avoid any questions that could imply victim-blaming, as these can erode rapport and hinder empowerment.

Assessing Risk and Mental Status

Alongside validation, a comprehensive risk assessment and mental status examination are critical components of the battered woman syndrome diagnosis process. Many women experiencing domestic violence may also struggle with other mental health conditions, in addition to PTSD and BWS. To evaluate the ongoing risk of abuse, inquire about the history of violence. Ask the woman to describe:

- The first abusive incident she remembers.

- The worst or one of the worst episodes.

- The most recent instance of abuse before seeking help.

- Typical patterns of abusive behavior.

These inquiries typically provide sufficient information to determine the level of lethality and immediate danger. Understanding patterns of violence, as illustrated in the Figure below, can further assist in assessing the level of danger.

Treatment Approaches for Battered Woman Syndrome

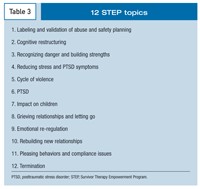

Developing a collaborative treatment plan is essential. The Survivor Therapy Empowerment Program (STEP) has proven effective in both individual and group settings (See Table 3).

Table 3: Core Units of the Survivor Therapy Empowerment Program (STEP)

| Unit | Topic | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to Survivor Therapy | Building safety and trust, program overview |

| 2 | Defining Abuse and Battered Woman Syndrome | Psychoeducation about abuse dynamics and BWS |

| 3 | Impact of Abuse on Mental and Physical Health | Understanding the wide-ranging effects of abuse |

| 4 | Challenging Self-Blame and Negative Self-Talk | Cognitive restructuring to combat internalized blame and negative thoughts |

| 5 | Identifying and Managing Trauma Triggers | Recognizing and coping with triggers that evoke traumatic memories |

| 6 | Developing Coping Skills | Relaxation techniques, stress management, and healthy coping strategies |

| 7 | Assertiveness and Communication Skills | Building assertive communication to set boundaries and express needs |

| 8 | Safety Planning and Self-Protection | Creating and implementing safety plans for current and future safety |

| 9 | Legal and Advocacy Resources | Information about legal options, restraining orders, and support services |

| 10 | Healthy Relationships | Education on healthy relationship dynamics and identifying red flags |

| 11 | Grief and Loss | Addressing grief related to the abuse and relationship |

| 12 | Moving Forward and Relapse Prevention | Strategies for long-term well-being and preventing future abuse |

It is important to evaluate a woman’s resilience alongside the severity of her PTSD symptoms, including re-experiencing, hypervigilance, arousal, and avoidance behaviors. While exploring childhood history can be valuable, it is often not the initial priority. Research indicates that while a significant percentage of battered women have experienced childhood abuse, many are not ready to discuss these experiences at the outset of treatment and may disclose them later as therapy progresses.

Early research highlighted that factors like learned helplessness and substance abuse, rather than mental illness or prior trauma, were significant barriers for women seeking to escape abusive relationships. Women with multiple trauma histories may have diminished resilience in coping with current abuse. Psychotherapists should adopt a gradual approach to treatment, regardless of whether past trauma is immediately addressed. Medication may be considered when appropriate, but the woman’s active participation in decision-making is crucial to foster a sense of control over her life.

Initially, cognitive techniques often prove more effective than affective approaches for battered women. However, both domains should eventually be integrated into the treatment plan. As cognitive clarity improves, attention, concentration, and memory are enhanced. In the initial interview, a woman’s anxiety may impair her recall and comprehension. Providing a resource card listing local shelters and support services can be helpful. Repetition and reinforcement of key information are important, especially until the woman’s cognitive functions stabilize.

Encouraging women to engage in diverse activities and social interactions can help counter isolation and the abuser’s control. It is crucial to emphasize that danger may persist even if the abuser completes a treatment program.

Therapy Options: Integrating Feminist and Trauma-Informed Approaches

Treatment for PTSD and BWS often involves a combination of feminist and trauma therapies. Feminist therapy acknowledges the inherent power dynamics within the therapist-client relationship and recognizes societal gender inequalities that contribute to women’s vulnerability to abuse. Understanding situational factors beyond a woman’s control, such as gender inequality, can help her focus on areas where she can exert influence and make changes.

Legal action can be empowering, particularly when women utilize domestic violence statutes to obtain protective orders, pursue arrest, or mandate batterer intervention programs. Divorce proceedings, while stressful, are another legal avenue. In cases of significant financial disparity, personal injury tort lawsuits may be considered, though these can be demanding and protracted.

Trauma therapy helps women understand that their psychological responses are normal reactions to trauma, not signs of “craziness.” Trauma-specific techniques are essential to overcome psychodynamic barriers that impede healing. Focusing on external trauma triggers, rather than solely on internal issues, can facilitate symptom reduction in BWS.

Briere and Scott’s trauma therapy model emphasizes sequential steps for abuse survivors. Modifying family system dynamics, even dysfunctional ones, can be risky and requires careful planning and safety considerations.

Identifying and managing trauma triggers is crucial. Common triggers include sensory cues associated with abuse, such as facial expressions, verbal abuse, specific phrases, or even smells. Behavioral techniques, such as relaxation training, guided imagery, and gradual exposure to triggers, can reduce their potency. Startle responses and hypervigilance are often the last BWS symptoms to subside and may persist long-term, potentially affecting new relationships. Open communication and patience from new partners are essential to navigate these challenges in subsequent non-abusive relationships. Contrary to popular myths, research indicates that only a small percentage of battered women enter new abusive relationships.

STEP effectively integrates feminist and trauma therapy principles. This empirically validated 12-unit program is beneficial for women facing substance abuse and interpersonal violence. Adapted shorter versions are used in institutional settings like jails or treatment centers, while longer, more in-depth sessions are common in clinics and private practice. Client satisfaction with STEP is consistently high and correlates with reduced anxiety levels.

Resources like DVDs demonstrating feminist therapy approaches with domestic violence survivors and models of long-term treatment are available for further learning and professional development.

Legal Considerations and Battered Woman Syndrome

Many battered women face complex legal challenges. Psychotherapists play a vital role in supporting them through legal processes, clarifying their options, and assisting them in providing necessary information to legal counsel. The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) offers various legal remedies, recognizing abuse as a violation of human rights and enabling federal civil rights lawsuits.

Child custody disputes are frequent and emotionally charged. While laws generally favor equal parental access, batterers often exploit children to maintain control post-separation, making shared parenting arrangements dangerous and impractical. Paradoxically, mothers prioritizing child protection from abusive fathers may be mischaracterized as engaging in “parental alienation” or similar unsubstantiated syndromes, potentially leading to loss of custody and even visitation rights. (Organizations like the Leadership Council provide resources on the dangers children face post-separation).

Mothers who lose custody often experience depression and exacerbated trauma symptoms, hindering their ability to navigate the legal system without adequate resources and support. Children in these situations may remain at risk of abuse, even without custody, particularly if they fail to comply with the batterer’s demands.

In rare, extreme cases, battered women may kill their abusers in self-defense. Statistics reveal that far fewer women kill their abusers than are killed by them. The most lethal period for a woman is when the abuser perceives the relationship as ending, as batterers frequently threaten lethal violence to prevent separation.

Staying in the abusive relationship may paradoxically seem safer than leaving, especially when children are involved. Court mandates for shared parental responsibility can undermine a mother’s protective capacity. In some cases, the abuser’s rage and decompensation may escalate upon separation, leading to extreme violence against the woman and children. Such tragedies are often reported in the media, sometimes lacking crucial context regarding the history of abuse.

Understanding BWS symptoms is critical in legal contexts, particularly in cases where battered women kill in self-defense. Explaining BWS can help juries understand the reasonableness of a woman’s perception of imminent danger, even if not immediate. Highlighting the fear and desperation triggered by perceived threats of violence is essential. Therapy records documenting the woman’s history of abuse and fear can be invaluable evidence in forensic evaluations.

Conclusion: Hope and Healing After Abuse

Battered woman syndrome, a recognized form of PTSD, can develop in women subjected to intimate partner violence. Like other trauma-related conditions, BWS symptoms can improve once a woman achieves safety and escapes the abusive environment. However, psychotherapy is often essential to facilitate healing and empower women to regain control over their lives. Medication may also be a beneficial adjunct in some cases.

BWS symptoms may resurface during new stressors or traumas, even after recovery. Empowerment can be fostered through legal actions like restraining orders and the arrest of abusers. Conversely, stressful litigation, particularly contentious child custody battles, can exacerbate trauma. Mental health professionals play a vital role in supporting abused women through these challenging periods, prioritizing safety and minimizing the risk of further harm.

The prognosis for battered women with BWS is ultimately hopeful. With appropriate support and intervention, most women recover, raise their children, and build fulfilling lives free from abuse and control.

References

References

1. Bureau of Justice Statistics Selected Findings. Violence Between Intimates (NCJ-149259). Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; November 1994.

2. Brown LS. Subversive Dialogues: Theory in Feminist Therapy. New York: Basic Books; 1994.

3. Walker LE. The Battered Woman. New York: Harper & Row; 1979.

4. American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Violence and the Family. Violence and the Family. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1996.

5. Goodman LA, Koss MP, Fitzgerald LF, et al. Male violence against women. Current research and future directions. Am Psychol. 1993;48:1054-1058.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the US.Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/ipv_cost/ipv.htm. Accessed May 19, 2009.

7. American Psychological Association. Final Report of APA Working Group on Investigation of Memories of Childhood Abuse. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1996.

8. Walker LE. The Battered Woman Syndrome.3rd ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2009.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

10. Briere JN, Scott C. Principles of Trauma Therapy: A Guide to Symptoms, Evaluation, and Treatment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2007.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system 2005 report; 2006. http://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/data/brfss/2005summarydataqualityreport.pdf. Accessed May 19, 2009.

12. Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, et al. Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite case control study. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1089-1097.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse health conditions and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence-United States, 2005 [published correction appears in MMWR. 2008;57:237]. MMWR. 2008;57:113-117.

14. Charney DS, Deutch AY, Krystal JH, et al. Psychobiologic mechanisms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:295-305.

15. Babcock JC, Green CE, Robie C. Does batterers’ treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clin Psychol Rev.2004;23:1023-1053.

16. Walker LE. Abused Women and Survivor Therapy: A Practical Guide for the Psychotherapist. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1994.

17. Browne A. Violence against women by male partners. Prevalence, outcomes, and policy implications. Am Psychol. 1993;48:1077-1087.

18. Walker LE. FeministTherapy: Psychotherapy With the Experts Series.Needham Heights, MA: Allyn &Bacon; 1998.

19. Walker LE. The Abused Woman: ASurvivor Therapy Approach. Assessment and Treatment of Psychological Disorders Video Series.http://www.psychotherapy.net/video/Abused_Woman. Accessed July 1, 2009.

20. Bancroft L, Silverman JG. The Batterer as a Parent: Addressing the Impact of Domestic Violence on Family Dynamics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2002.

21. Edleson JL. The overlap between child maltreatment and woman battering. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:134-154.

22. Clements CM, Sabourin CM, Spiby L. Dysphoria and hopelessness following battering: the role of perceived control, coping, and self-esteem. J Family Violence. 2004;19:25-36.

23. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Murder in Families (NCJ-143498). Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 1994.

24. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Family Violence Statistics: Including Statistics on Strangers and Acquaintances. US Department of Justice. http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/abstract/fvs.htm. Accessed May 19, 2009.

For More Information

• American Psychological Association Ad Hoc Committee on Legal and Ethical Issues in the Treatment of Interpersonal Violence. Potential Problems for Psychologists Working With the Area of Interpersonal Violence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997.

• US Department of Justice. Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). 2005. http://www.ovw.usdoj.gov/regulations.htm.