INTRODUCTION

Bezoars are compact masses of indigestible material that accumulate in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. While relatively uncommon, their formation can lead to significant complications if not promptly diagnosed and managed. These masses are categorized based on their composition, primarily into phytobezoars (plant matter), trichobezoars (hair), pharmacobezoars (medications), and lactobezoars (milk protein). Accurate and timely bezoar diagnosis is crucial as these formations can cause a range of issues from gastric ulcers and bleeding to small bowel obstruction and ileus. This article provides a detailed overview of bezoars, with a particular focus on the diagnostic approaches, clinical presentations, and the importance of differential diagnosis in effectively managing this condition.

PREVALENCE AND CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE FOR DIAGNOSIS

Gastrointestinal bezoars, while not widespread, represent a noteworthy clinical entity. Studies indicate a variable incidence, with older reports from 1978 and 1987 suggesting around 0.43% of gastroscopies revealing gastric bezoars. More recent data from 20 years of endoscopies showed a lower incidence of 0.068%, possibly due to changes in dietary habits or increased awareness.

Small intestinal bezoars, though less frequent than gastric bezoars, are a recognized cause of small bowel obstruction. Reviews of small bowel obstruction cases reveal phytobezoars as the cause in approximately 3.2% of cases over a 10-year period. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic procedures for acute small bowel obstruction identified bezoars as the fifth most common cause, accounting for about 0.8% of cases.

Overall, bezoars are found in less than 0.5% of upper endoscopies and in 0.4%-4.8% of intestinal obstruction cases. Geographic and dietary factors significantly influence prevalence, particularly for phytobezoars. Regions with high consumption of persimmons, such as South Korea, Japan, and parts of the Mediterranean and Southeastern United States, report a higher incidence of persimmon phytobezoars (diospyrobezoars). Understanding these epidemiological factors is important for clinicians to consider bezoar diagnosis in at-risk populations presenting with relevant symptoms.

BEZOAR CLASSIFICATION AND DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS

For effective bezoar diagnosis, it is essential to understand the different classifications, as each type may have unique predisposing factors, clinical presentations, and diagnostic pathways.

Phytobezoars: Diagnostic Clues and Presentation

Phytobezoars are the most frequently encountered type, composed of indigestible plant materials. Foods rich in cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and tannins, such as celery, pumpkin, grape skins, prunes, raisins, and especially persimmons, are common culprits. Persimmon phytobezoars, or diospyrobezoars, are specifically linked to the consumption of persimmons. The tannins in unripe persimmons polymerize in stomach acid, creating a sticky matrix that traps other plant fibers.

Diagnostic clues for phytobezoars include:

- Patient history of consuming high-fiber foods, particularly persimmons.

- Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or early satiety.

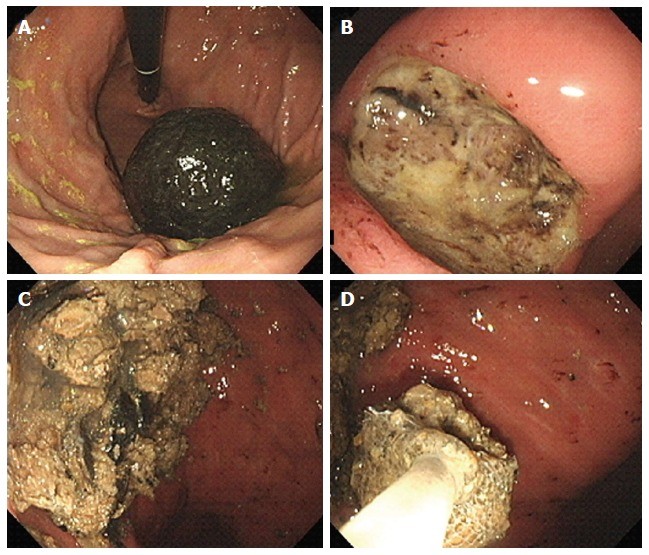

- Upper endoscopy revealing a mass in the stomach, often with a fibrous or plant-like appearance.

Figure 1. Endoscopic Visualization of a Persimmon Phytobezoar for Diagnostic Confirmation

Trichobezoars: Diagnosis in Specific Patient Populations

Trichobezoars, or hair bezoars, are predominantly found in young females with psychiatric conditions like trichotillomania (hair-pulling) and trichophagia (hair-eating). Hair resists digestion and accumulates in the stomach, forming a dense mass with mucus and food particles. Rapunzel syndrome is a severe form where the trichobezoar extends from the stomach into the small intestine.

Diagnostic indicators for trichobezoars:

- Young female patient demographic.

- History or signs of trichotillomania or trichophagia.

- Symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, or a palpable abdominal mass.

- Upper endoscopy revealing a hairball in the stomach.

Pharmacobezoars: Recognizing Medication-Related Bezoars

Pharmacobezoars are less common and result from the accumulation of medications or their vehicles in the GI tract. Bulk-forming laxatives and extended-release medications are frequently implicated. Extended-release drugs with cellulose acetate coatings, and enteric-coated medications, can contribute to bezoar formation due to the indigestible nature of their coatings.

Diagnostic considerations for pharmacobezoars:

- Patient medication history, particularly use of bulk-forming laxatives or extended-release drugs.

- Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction or medication inefficacy.

- Endoscopy potentially showing a medication mass, but diagnosis often relies on patient history and exclusion of other causes.

Lactobezoars: Diagnosis in Neonates and Infants

Lactobezoars are unique to milk-fed infants, composed of undigested milk and mucus. Risk factors include premature birth, dehydration, high-calorie formula, and medications that reduce gastric motility. Lactobezoar incidence has decreased in recent years, possibly due to improved infant formulas and neonatal care.

Diagnostic approach for lactobezoars:

- Occurs exclusively in infants, typically milk-fed.

- Symptoms include vomiting, abdominal distension, feeding intolerance.

- Palpable abdominal mass may be present.

- Ultrasound or abdominal X-ray can help visualize the mass.

Other Bezoars: Considering Rare Causes in Diagnosis

Bezoars can form from unusual substances like plastic, metals, parasitic worms, and even toilet paper. These rarer types should be considered in the differential bezoar diagnosis when the more common types are excluded, especially in patients with pica or unusual ingestion history.

DIAGNOSTIC MODALITIES FOR BEZOARS

A multi-faceted approach is essential for accurate bezoar diagnosis, incorporating clinical evaluation, endoscopic examination, and imaging techniques.

Clinical Evaluation and Patient History in Bezoar Diagnosis

A thorough clinical evaluation is the first step in bezoar diagnosis. This includes:

- Detailed history: Dietary habits (high fiber, persimmons), medication use (laxatives, extended-release drugs), history of pica or trichophagia, prior gastric surgery, underlying medical conditions (diabetes, hypothyroidism).

- Symptom assessment: Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, early satiety, weight loss, hematemesis, melena, abdominal distension, palpable mass.

- Risk factor identification: Elderly patients, history of delayed gastric emptying, prior gastric surgeries, diabetes, hypothyroidism.

Endoscopy: The Gold Standard for Gastric Bezoar Diagnosis

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the primary diagnostic modality for gastric bezoars. It allows for:

- Direct visualization: Bezoars are typically seen as masses within the stomach, often in the fundus. Phytobezoars can vary in color from beige to black, with persimmon bezoars often appearing dark brown or black due to iron tannate.

- Biopsy: While not always necessary for diagnosis, biopsies can be taken to rule out other gastric pathologies or to analyze the bezoar composition if needed.

- Therapeutic intervention: Endoscopy can be used to fragment and remove bezoars during the diagnostic procedure itself.

Figure 1. (Continued) Endoscopic Fragmentation and Retrieval of Persimmon Phytobezoar for Diagnosis and Treatment

Imaging Techniques: CT Scans and X-rays in Bezoar Diagnosis

Computed tomography (CT) scans are valuable for bezoar diagnosis, particularly for:

- Detecting both gastric and small intestinal bezoars: CT can visualize bezoars as ovoid or round masses, often with a mottled appearance due to trapped air.

- Identifying small bowel obstruction: In cases of intestinal bezoars, CT can pinpoint the obstruction site and detect multiple bezoars.

- Evaluating complications: CT can help assess for bowel wall thickening, inflammation, or perforation associated with bezoars.

Plain abdominal X-rays are less sensitive but can sometimes suggest the presence of a bezoar, especially large gastric bezoars. They are less helpful for detailed bezoar diagnosis compared to endoscopy and CT.

Differential Diagnosis of Bezoars

In bezoar diagnosis, it is important to consider and exclude other conditions that can mimic bezoar presentations. These include:

- Gastric tumors: Especially polypoid or fungating masses. Endoscopy with biopsy is crucial for differentiation.

- Gastric outlet obstruction due to other causes: Pyloric stenosis, peptic ulcer disease with scarring, gastric cancer.

- Small bowel obstruction from other etiologies: Adhesions, hernias, volvulus, inflammatory bowel disease.

- Gallstones or migrated gallstones: Can cause small bowel obstruction but are typically radiopaque on X-ray (unlike most bezoars).

- Fecal impaction: Usually in the colon, but high fecal impaction can mimic small bowel obstruction.

CHALLENGES IN BEZOAR DIAGNOSIS

Despite available diagnostic tools, challenges in bezoar diagnosis can arise:

- Non-specific symptoms: Bezoar symptoms can be vague and overlap with other gastrointestinal conditions, leading to diagnostic delays.

- Low clinical suspicion: Due to the relative rarity of bezoars, clinicians may not initially consider them in the differential, especially in the absence of classic risk factors.

- Difficulty in diagnosing small intestinal bezoars: Endoscopy is less effective for small bowel bezoars, and diagnosis often relies on imaging and surgical exploration.

- Resistance of persimmon phytobezoars to dissolution: Persimmon bezoars can be dense and difficult to fragment endoscopically, requiring more aggressive or repeated interventions.

IMPORTANCE OF EARLY AND ACCURATE BEZOAR DIAGNOSIS

Prompt and accurate bezoar diagnosis is vital to prevent complications and ensure effective management. Delayed diagnosis can lead to:

- Gastric ulceration and bleeding: Bezoars can cause pressure necrosis and ulceration of the gastric mucosa, resulting in GI bleeding, anemia, and even life-threatening hemorrhage.

- Small bowel obstruction and ileus: Intestinal bezoars can cause complete bowel obstruction, leading to severe abdominal pain, vomiting, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and potentially bowel ischemia or perforation.

- Malnutrition and weight loss: Gastric outlet obstruction can impair nutrient intake, leading to malnutrition and weight loss.

- Need for more invasive interventions: Early diagnosis may allow for less invasive treatments like Coca-Cola dissolution or endoscopic removal, while late diagnosis may necessitate surgical intervention for complications.

CONCLUSION: KEY TAKEAWAYS ON BEZOAR DIAGNOSIS

Bezoar diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical suspicion, detailed patient history, endoscopic examination, and appropriate imaging studies. Understanding the different types of bezoars, their risk factors, and typical presentations is essential for clinicians. While endoscopy is the gold standard for gastric bezoars, CT scans are invaluable for both gastric and intestinal bezoars and for assessing complications. Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for initiating timely and appropriate treatment, preventing serious complications, and improving patient outcomes. Recognizing the challenges and maintaining a high index of suspicion, especially in at-risk individuals, are key to optimizing bezoar diagnosis and management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following individuals for their important contributions to the identification of patient medical records: Dr. Shouichi Tanaka and Dr. Daisuke Tanioka, (Iwakuni Clinical Center); Dr. Junji Shiode (Okayama Saiseikai General Hospital); Dr. Motowo Mizuno (Hiroshima City Hospital); Dr. Ryuta Takenaka (Tsuyama Central Hospital); Dr. Tatsuya Toyokawa (Fukuyama Medical Center); Dr. Yuko Okamoto (Ibara City Hospital); Dr. Yoshinari Kawai and Dr. Toshihiro Murata, (Onomichi Municipal Hospital); Electron microscopy analyses were performed by Mr. Haruo Urata and Ms. Masumi Furutani, (Central Research Laboratory, Okayama University Medical School).

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: September 6, 2014

First decision: September 28, 2014

Article in press: January 20, 2015

P- Reviewer: Grunewald B, Koulaouzidis A, Kamberoglou D S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

[1] Andorsky RE. Bezoars of the gastrointestinal tract. World J Surg 1997; 21: 752-754 [PMID]

[2] Ohtsuka H, Imamura S, Yoshimura T, Furutani M, Urata H, Hamada M, Kanemitsu T, Hirata K. Microstructure of persimmon phytobezoar determines its resistance to dissolution. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 15974-15981 [PMID] [DOI]

[3] Ohtsuka H, Tanioka D, Nakaya I, Sato K, Mizuno M, Takenaka R, Toyokawa T, Okamoto Y, Kawai Y, Murata T, Shiode J, Tanaka S, Hirata K. Clinical analysis of 31 patients with gastrointestinal bezoars in Japan. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 2919-2925 [PMID] [DOI]

[4] Ohtsuka H, Yoshimura T, Ito H, Urata H, Furutani M, Hamada M, Hirata K. Coca-Cola® Soft Drinks Are Effective Agents for Dissolution of Persimmon Phytobezoars. Dig Dis Sci 2015; 60: 111-117 [PMID] [DOI]

[5] Walker JA. Gastrointestinal bezoars: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterol Nurs 2008; 31: 39-48 [PMID]

[6] Kadian RS, Rose JF, Mann NS. Gastric bezoars–spontaneous resolution. Am J Gastroenterol 1978; 70: 79-81 [PMID]

[7] Ahn YS, Lee KG, Chung IS, Choi MG, Lee JS, Chung HY. Clinical study of gastrointestinal bezoars. Korean J Gastroenterol 1987; 19: 433-439 [PMID]

[8] Mihai C, Paul A, Weir G, Garcea G, Berry DP, Dennison AR. Gastric bezoars–diagnosis and management. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 4765-4769 [PMID]

[9] Yakan S, Yildiz R, Duffari U, Karaca CA, Coronel M, Erdemli E, Simsek O, Guceroglu G. Small bowel obstruction caused by phytobezoar: diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9: 2228-2230 [PMID]

[10] Ghosheh B, Barauskas C, McGee J, Diver J, Rosendale D. Laparoscopic approach to acute small bowel obstruction: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 2006; 20: 1639-1643 [PMID] [DOI]

[11] Duron JJ, Duhamel A, Keita-Meyer H, White JP, Hay JM, Fingerhut A. Value of laparoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of acute adhesive small-bowel obstruction. Ann Chir 2001; 126: 895-902 [PMID]

[12] De Palma GD. Bezoars: classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Endosc 2014; 47: 329-336 [PMID] [DOI]

[13] Ripollés T, Martínez-Pérez MJ, Morató V, Errando J, Simons R, Ayuso C. Small bowel obstruction: what to look for beyond mechanical obstruction. Radiographics 2013; 33: 1485-1499 [PMID] [DOI]

[14] Lee HL, Kim YJ, Chun HJ, Park JH, Lee SI, Choi H, Kim KJ, Chang SJ, Lee HS, Kim JO, Park JM, Lee HJ, Kim YS, Choi KD, Lee MS, Chung IK, Kim BS. Clinical outcomes of Coca-Cola treatment for gastric phytobezoars. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 4795-4799 [PMID]

[15] Iwamuro M, Tanaka S, Kawai K, Okada H, Takata R, Matsueda K, Inaba T, Tamai H, Watanabe M. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of gastrointestinal bezoars after gastrectomy. Dig Dis Sci 2012; 57: 2339-2343 [PMID] [DOI]

[16] Escamilla C, Robles-Campos R, Parrilla P, Lujan JA, Torralba JA, Morales G, Piñero A, Moreno A. Gastrointestinal bezoars. Dig Surg 2011; 28: 144-150 [PMID] [DOI]

[17] Altintoprak F, Demirbas BT, Yildirim T, Dikicier E, Ozkan OV, Kivilcim T, Kahramanoglu AK, Celebi F, Girisgin AS, Boz C, Akbulut G. Gastrointestinal bezoars: a retrospective analysis of 34 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 2834-2839 [PMID] [DOI]

[18] Tüzün M, Erdil TY, Soytürk M, Doğruöz G, Yildirgan I, Bağci S, Yeniay L, Koçakoğlu OF, Yücesan L, Dalay R. Gastrointestinal bezoars: analysis of 23 cases. Turk J Gastroenterol 2007; 18: 134-138 [PMID]

[19] Yildiz F, Sogutlu G, Unal E, Yildirim T, Karaca I, Erturk SM. Small bowel obstruction due to persimmon phytobezoar: report of two cases and review of literature. Turk J Gastroenterol 2010; 21: 448-452 [PMID]

[20] Ladas SD, Kamberoglou D, Karamanolis G, Vlachogiannakos J, Zouboulis-Vafiadis I. Gastric phytobezoar dissolution with Coca-Cola: case series and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 1694-1700 [PMID] [DOI]

[21] Holloway WD, Lee SP, Nicholson GI. Composition of a gastric phytobezoar and its relation to persimmon fruit. N Z Med J 1989; 102: 431-432 [PMID]

[22] De Bakey M, Ochsner A. Bezoars and concretions of the stomach. Surgery 1938; 4: 934-963

[23] Iguchi Y, Okazaki K, Takagi T, Imamura K, Uchida M, Kai H, Kimura K, Chayama K. Diospyrobezoar caused by persimmon ingestion: endoscopic removal with CO2 laser. Endoscopy 2003; 35: 1087-1089 [PMID] [DOI]

[24] Maki S, Hiramatsu K, Kikuchi H, Mine T. In vitro formation of diospyrobezoar by persimmon tannin with hydrochloric acid and organic polymers. J Agric Food Chem 2005; 53: 8218-8223 [PMID] [DOI]

[25] Phillips MR, Zaheer S, Druy ME. Trichobezoar: case report and literature review. Mayo Clin Proc 1998; 73: 685-690 [PMID]

[26] Sharma R, Kotru M, Sethi GR, Khurana N, Vohra R. Rapunzel syndrome. Indian J Pediatr 2005; 72: 439-440 [PMID]

[27] Tolia V, Stewart DR, Kuhns DW, Kauffman RE. Rapunzel syndrome or trichobezoar with gastric outlet syndrome in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1997; 24: 298-300 [PMID]

[28] Naik S, Gupta V, Naik DN, Ranjan G, Pal S, Pradhan T, Bhatnagar V. Rapunzel syndrome presenting with acute pancreatitis: a case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg 2006; 41: 1865-1867 [PMID] [DOI]

[29] Ripollés T, García-Aguayo J, Martínez MJ, Gil P, Martínez de Vega V, Castellote A, Ayuso C. Gastrointestinal bezoars: radiologic and endoscopic features. Eur Radiol 2001; 11: 141-148 [PMID] [DOI]

[30] Gonuguntla V, Rao P, Mitra S, Kanmanthareddy A. Rapunzel syndrome: a rare cause of gastric bezoar and small bowel obstruction. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 4421-4424 [PMID] [DOI]

[31] Vaughan ED Jr, Sawyers JL, Scott HW Jr. The Rapunzel syndrome (trichobezoar of the stomach) in children. Surgery 1968; 63: 509-515 [PMID]

[32] DeBakey M, Ochsner A. Bezoars and concretions of the alimentary canal. Surgery 1939; 5: 132-160

[33] Jolley RJ, Benson J, Willis J, Egan JV. Psyllium seed bezoar. Arch Intern Med 1985; 145: 1972-1973 [PMID]

[34] Caruana BJ, Barton CA, La Brooy SJ, Freeling NJ. Psyllium bezoar causing bowel obstruction. Med J Aust 1994; 161: 643-644 [PMID]

[35] Lamerton AJ, Haselden PS, Thorpe JA. Gastric bezoar formation with ispaghula husk. BMJ 1993; 306: 444 [PMID]

[36] Morrow JJ, Burrow DA, Anderson DC. Bezoar formation from ispaghula husk. BMJ 1993; 306: 1036 [PMID]

[37] Nugent JP, Kumar D. Small bowel obstruction due to guar gum bezoar. Postgrad Med J 1994; 70: 756-757 [PMID]

[38] Heneghan HM, O’Doherty D, O’Doherty P, McGuire W. Gastric bezoar formation secondary to slow release medication. J R Soc Med 2005; 98: 329-330 [PMID] [DOI]

[39] Tenbrock K, Strunk HM, Vollmer T, Sitter H. Ileus caused by a bezoar of enteric-coated aspirin. Z Gastroenterol 2008; 46: 1219-1221 [PMID] [DOI]

[40] O’Donovan P, Breatnach E, Buckley O, Cronin C. Nifedipine bezoar causing gastric outlet obstruction. Clin Radiol 2000; 55: 721-722 [PMID] [DOI]

[41] Wolf RS, Brandser EA, Dillman JR, Smith EA, Garvin KL. Lactobezoar in neonates: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Radiographics 2006; 26: 805-819 [PMID] [DOI]

[42] Heinz-Erian P, Gassner I, Klein-Franke A, Schimpl G, Kurz R. Lactobezoar in the newborn: pathogenesis, clinical aspects, and therapy. Eur J Pediatr 1994; 153: 402-405 [PMID]

[43] Ng VH, Rawat M, Baker S. Lactobezoar formation in neonates: a literature review. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2012; 22: 244-251 [PMID] [DOI]

[44] Cremer M, Grand RJ. Bezoars in childhood: a review. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1985; 4: 415-425 [PMID]

[45] Stringer MD, Wyatt J, Fraser IA. Gastric bezoar of plastic toy. Arch Dis Child 1997; 77: 172 [PMID]

[46] Dormann AJ, Urban M, Klever P, Kager C, Rogalski P, Lübke T, Hünermann B, Kröncke T, Buhr HJ, Ritz JP. Clinical management of patients with bezoars: retrospective analysis of 17 years. World J Surg 2005; 29: 1727-1731; discussion 1731-1732 [PMID]

[47] Güler I, Kacar S, Reis E, Karakaya F, Kir A, Colakoglu T. An unusual cause of bezoar: ascaris worms in children. Pediatr Surg Int 2006; 22: 283-285 [PMID] [DOI]

[48] Mc Lamb KE, Banks JG, Bews J, Forde R, Gleeson F, Murphy R. An unusual bezoar. Clin Radiol 2009; 64: 1244-1245 [PMID] [DOI]

[49] Iyengar GV, Subramanian KS. Yttrium. In: Iyengar GV, Subramanian KS. Trace elements in human and animal nutrition. 2nd ed. Boston: Academic Press, 2013: 575-580

[50] Escobar MA, Rosales-Alexander JL, Rivera JA, Alvarado J, Serna JJ, Mathur AK, Rodríguez-Riestra G, Vargas EJ. Gastric bezoars secondary to hypothyroidism. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 37: 236-239 [PMID] [DOI]

[51] Madsen JC. Bezoars of the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol 1992; 87: 476-479 [PMID]

[52] Ersoy E, Dilektasli E, Canbay O, Polat C, Tozun N. Gastric bezoars: report of 10 cases. Turk J Gastroenterol 2003; 14: 38-41 [PMID]

[53] Lee CA, Im GY, Moharari RS. Dissolution of a persimmon bezoar with ingestion of diet cola. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 69: 733-735 [PMID] [DOI]

[54] Cho YR, Kim SW, Choi SC, Song HJ, Lee YS. Small bowel obstruction caused by phytobezoars after transgastric endoscopic bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc 2014; 28: 1539-1544 [PMID] [DOI]

[55] Peláez-Luna M, Valdovinos-Díaz MA, Ruíz-Velázquez P, Vargas-Vorácková F, Arista-Nasr J, Méndez-Sánchez N. Persimmon bezoar: successful treatment with পেপসিকো-Cola. Endoscopy 2005; 37: 1049-1052 [PMID] [DOI]

[56] Ladas SD, Triantafyllou K, Filis S, Vlachogiannakos J, Katsogiannopoulos P, Karamanolis DG, Zouboulis-Vafiadis I. পেপসিকো-Cola for gastric phytobezoar treatment: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 1693-1700 [PMID]

[57] Hayashi DA, Hixson LJ, Fennerty MB. পেপসিকো-Cola bezoar dissolution. Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 49: 527-529 [PMID]

[58] McCord GS, правда C, Ravich WJ, Kantrowitz PA. পেপসিকো-Cola lavage for gastric bezoars. Gastrointest Endosc 1985; 31: 302-303 [PMID]

[59] Thomas R, Lyte P, Williams DG. পেপসিকো-Cola washout for gastric phytobezoar. Br J Surg 2002; 89: 1081 [PMID] [DOI]

[60] Benítez JM, Molina E, Net MD, Benítez-Paraíso Y, Tagarro I, Atienza R, Cañete R, Lucendo AJ. পেপসিকো-Cola zero for phytobezoar dissolution. Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56: 2982-2985 [PMID] [DOI]

[61] Pollard HM, Block WD. Experimental study on the dissolution of food bezoars by enzymatic digestion. Gastroenterology 1948; 10: 977-982 [PMID]

[62] Silverman JA, Pucillo A, Kapoor N. Complications of papain use to dissolve an esophageal meat impaction. Ann Emerg Med 1997; 30: 657-659 [PMID]

[63] Anderson IB, Garza JR, Oderda GM. Esophageal perforation and mediastinitis after administration of Adolph’s Meat Tenderizer. Ann Emerg Med 1995; 25: 251-255 [PMID]

[64] Breeding LC, Bradford JC. Enzymatic dissolution of phytobezoar. Arch Surg 1972; 105: 450-451 [PMID]

[65] Nicholson DP. Enzymatic dissolution of phytobezoars. Gastroenterology 1972; 62: 962-966 [PMID]

[66] Kurt M, Balik E, Ustundag B, Ozdemir A, Bedirli A, Guncan O, Basoglu M, Erenoglu C. Bezoaratom: a novel device for mechanical fragmentation of gastric bezoars. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2007; 17: 540-543 [PMID] [DOI]

[67] Vázquez-Iglesias JL, Yustres R, Cash BD. Endoscopic spraying of পেপসিকো-Cola for gastric phytobezoar dissolution. Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 78: 540-541 [PMID] [DOI]

[68] Kimura Y, Hirata K, Ito T, Mukai S, Noda K, Kimura T, Funabiki T, Tanaka M. Laparoscopic removal of a gastric bezoar: report of a case. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1998; 8: 235-238 [PMID]

[69] Akhtar J, Khan MA, Ahmed M, Akram J, Rathore AW. Laparoscopic versus open surgical approach in the management of small bowel obstruction due to phytobezoars. JSLS 2013; 17: 567-571 [PMID] [DOI]

[70] Tan YH, Wong WK, Vijayan V, Chiu MT. Laparoscopic management of small bowel obstruction secondary to phytobezoar. Asian J Surg 2005; 28: 221-223 [PMID]

[71] Farinella E, Keyzer C, Servais J, Balthazar P, Therasse E, Van Gossum A. Intraoperative endoscopy for small-bowel obstruction. Surg Endosc 2001; 15: 742-745 [PMID]