Introduction

The advent of advanced imaging technologies has led to a significant increase in the detection of adrenal masses, often discovered incidentally. While most of these masses are unilateral and benign, bilateral adrenal masses represent a less common but clinically significant finding. Unlike their unilateral counterparts, bilateral adrenal masses often signal a broader spectrum of underlying conditions, ranging from benign hyperplasia and infiltrative lesions to malignant tumors and systemic diseases. Understanding the differential diagnosis of bilateral adrenal masses is crucial for effective clinical management, as the etiologies vary widely, each demanding a specific diagnostic and therapeutic approach.

The clinical presentation of bilateral adrenal masses is equally diverse, spanning from asymptomatic incidental findings to severe systemic manifestations. A critical aspect in evaluating bilateral adrenal masses is the potential for hypocortisolism, a condition where the adrenal glands fail to produce sufficient cortisol. This is particularly relevant in hyperplastic and infiltrative lesions that can compromise adrenal function. Furthermore, the presence of bilateral adrenal tumors raises the suspicion of hereditary or syndromic conditions, necessitating a thorough investigation for associated genetic predispositions.

Despite the clinical importance of bilateral adrenal masses, comprehensive data on their clinical profiles and diagnostic strategies remain limited. Much of the existing literature consists of isolated case reports and small case series, highlighting the need for larger studies to elucidate the complexities of this condition. Therefore, a systematic approach to evaluating patients with bilateral adrenal masses is paramount to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

This article aims to provide an in-depth guide to the differential diagnosis of bilateral adrenal masses, drawing upon a detailed analysis of clinical, biochemical, and radiological features, as well as management outcomes. By synthesizing existing knowledge with new insights, we propose a stepwise clinical approach to aid clinicians in navigating the diagnostic challenges posed by bilateral adrenal masses, ultimately improving patient care and outcomes. This comprehensive overview is specifically tailored to enhance understanding of Bilateral Adrenal Masses Differential Diagnosis for healthcare professionals.

Materials and Methods (Summary)

This study is based on a retrospective analysis of 70 patients diagnosed with bilateral adrenal masses at a tertiary care endocrine center in western India between 2002 and 2015. The research meticulously reviewed patient records, collecting data on clinical presentations, hormonal assessments, imaging findings (both anatomical and functional), treatment strategies, and patient outcomes. Standard biochemical evaluations included measurements of serum cortisol, ACTH, cortisol levels post-dexamethasone suppression, and plasma free metanephrines. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen was consistently performed, with specific protocols for adrenal mass imaging. Diagnostic criteria for specific lesions like cysts, myelolipomas, and adenomas were based on established radiological characteristics. Biopsies were performed when imaging was inconclusive or to confirm suspected malignancies or infections. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software to compare different etiologies.

Results

The study cohort comprised 70 patients with bilateral adrenal masses, with a slight male predominance (42 males, 28 females). The average age at presentation was approximately 40 years, with a wide age range (11-72 years). A significant majority (87.1%) of patients presented with symptoms, with an average symptom duration of 15 months.

Etiology Distribution: Pheochromocytoma emerged as the most prevalent etiology (40%), followed by tuberculosis (27.1%). Primary adrenal lymphoma (PAL) accounted for 10%, metastases for 5.7%, and non-functioning adenomas and primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (PBMAH) each constituted 4.3%. Other less common causes (8.6%) included histoplasmosis, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) with myelolipoma, cysts, and leiomyoma.

Age and Symptom Duration: Patients with pheochromocytoma and tuberculosis were notably younger at presentation compared to those with PAL and metastases. Symptom duration varied, with lymphoma and metastasis patients having shorter symptom durations compared to pheochromocytoma and tuberculosis.

Presenting Symptoms: Hyperadrenergic spells were characteristic of pheochromocytoma. Hypocortisolism was a dominant feature in tuberculosis and PAL. Abdominal pain was common across several etiologies, particularly metastases, PAL and pheochromocytoma. Asymptomatic presentation was noted in a subset of pheochromocytoma and adenoma cases.

Biochemical Findings: Hypocortisolism was universally present in tuberculosis and frequently observed in PAL.

CT Features: Mean tumor size varied across etiologies, with lymphoma and pheochromocytoma exhibiting larger sizes compared to tuberculosis. Specific CT characteristics, such as calcification in tuberculosis and washout patterns, were valuable in differential diagnosis.

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics of Bilateral Adrenal Masses by Etiology

| Characteristic | Pheochromocytoma (n=28) | Tuberculosis (n=19) | Lymphoma (n=7) | Metastases (n=4) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Patients: n (%) | 28 (40%) | 19 (27.1%) | 7 (10%) | 4 (5.7%) | – |

| Males: Females | 13:15 | 15:4 | 6:1 | 3:1 | 0.023 |

| Age (years) ± s.d. | 33.2 ± 16.5 | 41.5 ± 12 | 48.8 ± 12.5 | 61.5 ± 8.3 | a |

| Range | (11–65) | (21–60) | (30–67) | (60–72) | |

| Duration of Symptoms (months) ± s.d. | 19.1 ± 18.7 | 18.6 ± 25.1 | 3 ± 2.3 | 5.2 ± 2.2 | 0.16a |

| Range | (1–60) | (0.25–92) | (0.25–6) | (3–8) | |

| Presenting Symptoms | |||||

| 1. Hyperadrenergic Spell | 15 (53.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2. Hypocortisolism | 0 | 18 (94.7%) | 4 (57.1%) | 0 | b |

| 3. Abdominal Pain | 8 (28.5%) | 1 (5.2%) | 3 (42.8%) | 4 (100%) | c |

| 4. Asymptomatic | 5 (17.8%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12d |

| Biochemistry | |||||

| Hypocortisolism | 0 | 19 (100%) | 5 (71.4%) | 0 | |

| CT Features | |||||

| Mean Size (cm) ± s.d. | 4.8 ± 2.6 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 2.0 | 4 ± 0.6 | |

| Range | (1–15) | (1–4) | (2–8) | (3–5) | |

| 1. Right-sided Lesions (cm) ± s.d. | 4.7 ± 2.4 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 4.8 ± 2.1 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | |

| 2. Left-sided Lesions (cm) ± s.d. | 5 ± 2.9 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 2.2 | 4.2 ± 0.5 |

s.d., Standard deviation. aThe difference in the age at presentation and duration of symptoms for pheochromocytoma and tuberculosis, in comparison with that of lymphoma and metastases were statistically significant by student t-test; bSignificant between tuberculosis and lymphoma; cSignificant between pheochromocytoma and tuberculosis, tuberculosis and lymphoma, metastasis and all other groups together; dNot significant in between any pair of pathologies.

Discussion: Delineating the Differential Diagnosis of Bilateral Adrenal Masses

The findings of this study, the largest series to date on bilateral adrenal masses, underscore the diverse etiologies and clinical presentations associated with this condition. Pheochromocytoma, tuberculosis, and lymphoma emerged as the most common diagnoses, highlighting the importance of considering both neoplastic and non-neoplastic causes in the bilateral adrenal masses differential diagnosis.

Pheochromocytoma: The Predominant Neoplasm

Pheochromocytoma, a tumor arising from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla, was the most frequent cause of bilateral adrenal masses in this cohort. The younger age at presentation in pheochromocytoma patients, coupled with characteristic hyperadrenergic spells, provides critical diagnostic clues. Furthermore, the high incidence of syndromic and familial associations in bilateral pheochromocytoma, as observed in this study (approximately two-thirds of index cases), emphasizes the need for genetic screening in these patients. Conditions such as Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome and Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 2 (MEN2) are strongly linked to bilateral pheochromocytomas. Biochemically, elevated plasma metanephrines and urinary vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) are crucial for diagnosis, although, as demonstrated, urinary VMA can be less sensitive than plasma metanephrines. Imaging, particularly CT and MIBG scans, plays a vital role in confirming the diagnosis and assessing tumor characteristics.

Figure 1A: Axial CT image showing bilateral pheochromocytomas with intense contrast enhancement. This imaging characteristic is typical of pheochromocytomas and aids in differentiating them from other adrenal masses.

Adrenal Tuberculosis: A Significant Infectious Cause

Adrenal tuberculosis represented the second most common etiology, particularly relevant in regions with a higher prevalence of tuberculosis. The slightly older age group compared to pheochromocytoma, coupled with the dominant presentation of adrenal insufficiency (AI), is highly suggestive of tuberculosis. The presence of extra-adrenal tuberculosis, as observed in a significant proportion of patients, further strengthens this diagnosis. Radiologically, smaller tumor size and the frequent occurrence of adrenal calcification are characteristic features. While adrenal biopsy can confirm the diagnosis, the presence of extra-adrenal TB may obviate the need for biopsy in certain cases, provided there is clinical and radiological congruence. However, the case of histoplasmosis misdiagnosed as tuberculosis underscores the importance of considering other infections in the differential, especially in non-responders to anti-TB treatment.

Figure 1B: Axial CT image demonstrating bilateral adrenal tuberculosis with calcification in the left adrenal gland and poor contrast uptake. Calcification is a common finding in adrenal tuberculosis, helping to distinguish it from other adrenal pathologies.

Primary Adrenal Lymphoma: A Rare but Aggressive Malignancy

Primary adrenal lymphoma (PAL), although less frequent than pheochromocytoma and tuberculosis, is a critical consideration in the bilateral adrenal masses differential diagnosis due to its aggressive nature. The older age group, male predominance, and shorter symptom duration, often presenting with abdominal pain and AI, are typical features. The larger tumor size and mild contrast enhancement on CT, along with FDG-PET avidity, aid in differentiating PAL from adenomas and metastases. Adrenal biopsy is essential for definitive diagnosis, guiding the aggressive chemotherapy regimens required for PAL management.

Figure 1C: Axial CT image showing bilateral primary adrenal lymphoma with areas of necrosis and mild contrast enhancement. The presence of necrosis and moderate enhancement are typical features of adrenal lymphoma.

Adrenal Metastases: Considering Secondary Malignancy

Adrenal metastases, while less common in this endocrine-focused series, remain an important differential, particularly in patients with known primary malignancies or those presenting with abdominal pain and older age. The absence of AI in adrenal metastases in this study is noteworthy and can help differentiate them from other etiologies like tuberculosis and lymphoma which commonly present with AI. Radiologically, metastases often exhibit poor washout patterns on delayed CT imaging, distinguishing them from benign adenomas. In cases where a primary malignancy is not initially evident, thorough oncologic evaluation is warranted.

Figure 1D: Axial CT image illustrating bilateral adrenal metastases with areas of necrosis and mild contrast enhancement. Metastases often display necrotic areas and heterogeneous enhancement patterns.

Non-Functioning Adenomas and PBMAH: Benign Entities

Non-functioning adenomas and PBMAH, while benign, are part of the differential diagnosis, particularly in incidentally discovered bilateral adrenal masses. Non-functioning adenomas are often detected during screening for conditions like MEN1 or incidentally. PBMAH, on the other hand, may present with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome. These entities typically exhibit smaller size and benign imaging characteristics on CT.

Figure 1E: Axial CT image depicting bilateral adrenal adenomas with low baseline Hounsfield Units (HU). Low HU values on unenhanced CT scans are characteristic of lipid-rich adrenal adenomas.

Figure 1F: Axial CT image showing primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (PBMAH) with irregular adrenal masses. The irregular morphology is typical of PBMAH.

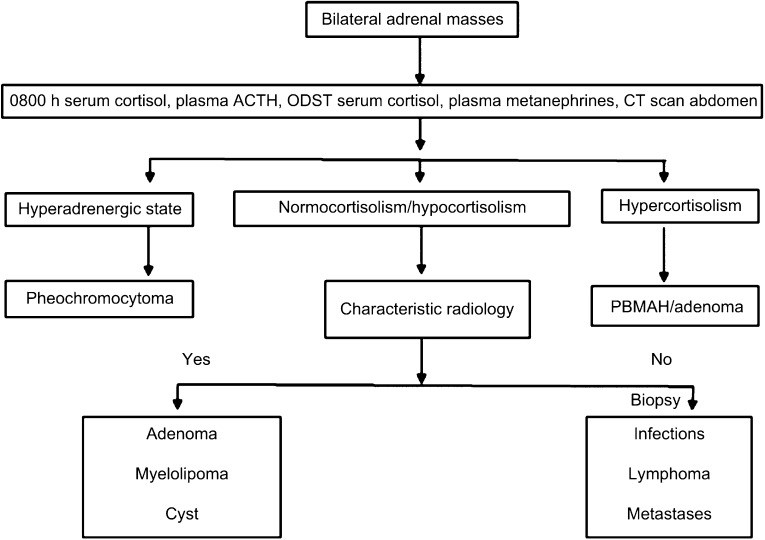

Stepwise Diagnostic Algorithm

Based on these findings, a stepwise diagnostic algorithm for bilateral adrenal masses differential diagnosis is proposed (Figure 3). The initial step involves a thorough clinical evaluation, including history, physical examination, and assessment of hormonal status. Evaluating for hypersecretion (pheochromocytoma, Cushing’s) and hyposecretion (adrenal insufficiency) is crucial. CT imaging is the cornerstone of radiological assessment, characterizing mass size, density, and enhancement patterns. In cases of suspected pheochromocytoma, biochemical testing for catecholamines and MIBG scans are indicated. For suspected tuberculosis, evaluation for extra-adrenal TB and consideration of adrenal biopsy are important, especially in the absence of extra-adrenal findings or in non-responders to anti-TB therapy. In cases with inconclusive imaging or suspicion of malignancy or lymphoma, adrenal biopsy is essential for definitive diagnosis.

Figure 3: Approach to bilateral adrenal masses

Figure 3: Approach to bilateral adrenal masses

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive overview of the bilateral adrenal masses differential diagnosis, emphasizing the spectrum of underlying etiologies and the importance of a systematic diagnostic approach. Pheochromocytoma, tuberculosis, and lymphoma are the most frequent causes in a non-oncologic endocrine setting. Age at presentation, presenting symptoms, lesion size, and biochemical profiles are valuable clinical parameters in guiding differential diagnosis. A structured diagnostic algorithm, integrating clinical assessment, hormonal evaluation, and radiological characteristics, is essential for accurate diagnosis and optimal management of patients with bilateral adrenal masses. Further research, particularly multi-center prospective studies, is warranted to refine diagnostic algorithms and improve clinical outcomes in this complex patient population.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.