Introduction to Edema and Diagnostic Approach

Edema, clinically recognized as palpable swelling due to an expanded interstitial fluid volume, arises from disturbances in fluid dynamics between intravascular and interstitial spaces, sodium and water retention by the kidneys, or both. Clinically evident edema typically requires an increase of 2.5 to 3 liters in interstitial volume. Understanding the underlying mechanisms—Starling’s law governing fluid movement across capillaries, renal sodium handling—is crucial for deciphering edema etiology. This guide focuses on the differential diagnosis of bilateral edema, contrasting it with unilateral edema to refine diagnostic strategies and patient management.

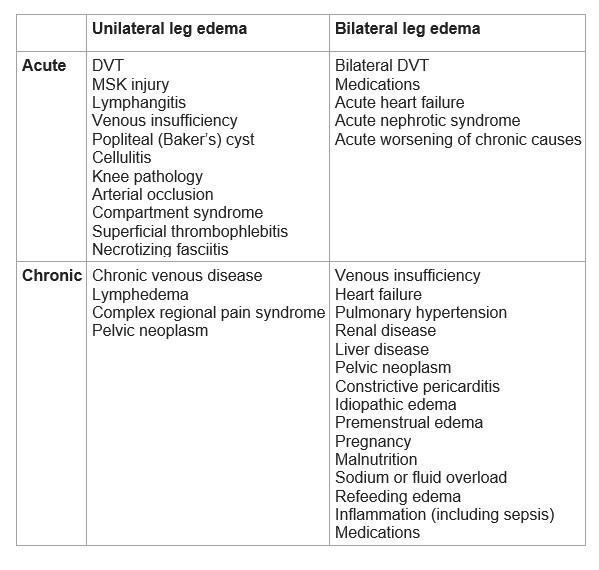

Diagnostic Process for Leg Edema: Unilateral vs. Bilateral

Leg edema can manifest unilaterally or bilaterally, each presentation suggesting different diagnostic pathways. Initial assessment should categorize edema as unilateral or bilateral and acute or chronic to narrow the differential diagnosis.

Acute Unilateral Leg Edema: Primarily Rule Out DVT

In acute unilateral leg edema, the immediate priority is to exclude deep vein thrombosis (DVT), a potentially life-threatening condition.

DVT Work-up:

- Pre-test Probability Assessment: Utilize scoring systems like the Wells score to estimate DVT likelihood.

- D-dimer Testing: In low pre-test probability cases (Wells score 0-1), a negative D-dimer test can effectively rule out DVT.

- Doppler Ultrasound: For high pre-test probability or positive D-dimer, Doppler ultrasound of the lower extremities is essential. Prompt anticoagulation should be initiated while awaiting ultrasound results, ideally within 24 hours.

- Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS): While bedside 3-point compression POCUS in the emergency department can be valuable, its accuracy is operator-dependent, necessitating consideration of pre-test probability, operator expertise, and follow-up.

Differential Diagnosis Post-DVT Exclusion:

Once DVT is ruled out, consider alternative causes of acute unilateral leg edema:

- Musculoskeletal Injuries (40%): Strains, tears, or twists, often with a clear injury history and exam findings like bruising.

- Idiopathic (26%): A significant proportion remains unexplained.

- Paralyzed Limb Swelling (9%): Edema in limbs affected by paralysis.

- Lymphangitis or Lymph Obstruction (7%): Inflammatory or obstructive lymphatic conditions.

- Venous Insufficiency (7%): Though more common in chronic edema, acute exacerbations can occur.

- Popliteal (Baker’s) Cyst (5%): Characterized by posterior knee pain, stiffness, and a palpable mass.

- Cellulitis (3%): Infection presenting with warmth, redness, and fever.

- Knee Abnormalities (2%): Intra-articular knee pathology causing swelling.

Chronic Unilateral Leg Edema: Venous and Lymphatic Considerations

Chronic unilateral leg edema frequently stems from chronic venous disease of the lower extremity.

Etiologies of Chronic Unilateral Edema:

- Chronic Venous Disease: History of thrombophlebitis, skin changes (hyperpigmentation, induration), and ulceration are typical.

- Lymphedema: Consider history of lymph node dissection or radiation therapy in the ipsilateral inguinal or pelvic region.

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS): Characterized by pain, edema, and skin color/temperature changes following limb trauma.

- Chronic DVT: Persistent venous obstruction post-DVT.

- Anatomic Obstruction: External compression or May-Thurner syndrome (iliac vein compression).

Diagnostic Approach for Chronic Unilateral Edema:

If the presentation is atypical or worsening, a compression ultrasound with Doppler is indicated.

- Normal Ultrasound: Suggests lymphedema or CRPS.

- Abnormal Venous Flow: Points towards chronic venous disease.

- Pelvic Outflow Obstruction: Suspect neoplasm, especially with constitutional symptoms like weight loss, warranting further pelvic imaging with venous contrast.

Acute Bilateral Leg Edema: Focus on Systemic Causes

Acute bilateral leg edema often signals systemic conditions, notably acute decompensated heart failure.

Key Etiologies and Diagnostic Steps:

- Heart Failure: Acute worsening is a primary concern. Assess for dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND), and fatigue. Utilize chest X-ray, BNP, echocardiography, and potentially ED POCUS for cardiac evaluation.

- Medications: Review medication history meticulously, identifying edema-inducing drugs (dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, vasodilators, hormone therapies).

- Acute Nephrotic Syndrome: Evaluate for renal involvement with urine dipstick for protein; if positive, quantify proteinuria with urine protein-creatinine ratio (PCR) and measure serum albumin.

- Bilateral DVT: Although less common than unilateral DVT, consider, especially in malignancy patients. For high pre-test probability, proceed directly to Doppler ultrasound. In others, D-dimer can be used as an initial screening tool.

Chronic Bilateral Leg Edema: Systemic Diseases Predominate

Chronic bilateral leg edema is frequently linked to systemic diseases. Chronic venous disease remains a common cause, often with visible skin changes.

Common Causes of Chronic Bilateral Edema:

- Chronic Venous Disease: As with chronic unilateral edema, but often bilateral and with more pronounced chronic venous insufficiency signs.

- Heart Failure: Chronic heart failure is a leading cause. Look for history of CHF, dyspnea, orthopnea, PND, abdominal distention, and fatigue.

- Pulmonary Hypertension: Consider in patients with sleep apnea, daytime sleepiness, snoring, and observed breathing interruptions during sleep.

Less Common but Important Etiologies:

- Renal Disease: Chronic kidney disease leading to fluid retention.

- Liver Disease: Cirrhosis and associated hypoalbuminemia.

- Pelvic Neoplasm: Causing venous or lymphatic obstruction.

- Constrictive Pericarditis: Restrictive cardiac physiology leading to systemic venous congestion.

- Idiopathic Edema: Edema without identifiable systemic cause, often in women.

- Premenstrual Edema: Hormonally influenced fluid retention.

- Malnutrition: Severe protein deficiency leading to decreased oncotic pressure.

Distinguishing True Edema from Edematous States:

Lymphedema and myxedema (severe hypothyroidism) are technically not true edematous states, but rather represent lymphatic fluid accumulation and tissue glycosaminoglycan deposition, respectively.

Further Investigations for Unclear Etiology:

If initial history and exam are non-diagnostic, initiate basic investigations:

- Urine dipstick for protein.

- Serum creatinine, albumin.

- PT/INR, liver function tests.

- TSH to exclude hypothyroidism.

If these are unremarkable, consider advanced cardiac and pelvic imaging:

- Echocardiogram to evaluate for heart failure or pulmonary hypertension.

- CT pelvis with contrast to rule out pelvic neoplasm if other investigations are negative and suspicion remains.

Quality of Evidence

The diagnostic and etiologic information presented is based on a moderate level of evidence. This reflects a consensus derived from a range of studies in relative agreement, although some studies may have limitations or variations in findings. While we are reasonably confident in the diagnostic approaches outlined, the possibility of deviation from the estimated effects exists, particularly in nuanced or complex presentations of leg edema.

Conclusion

The differential diagnosis of bilateral edema is broad, encompassing cardiac, renal, hepatic, and endocrine etiologies, among others. A systematic approach, differentiating acute from chronic and unilateral from bilateral presentations, is crucial. While unilateral edema often necessitates exclusion of DVT and consideration of local factors, bilateral edema frequently points towards systemic conditions requiring comprehensive evaluation. This guide provides a framework for clinicians to navigate the complexities of leg edema, emphasizing the importance of targeted investigations based on clinical context to achieve accurate diagnosis and effective management.

References

- García, Jorge Pedraza, et al. “Comparison of the accuracy of emergency department-performed point-of-care-ultrasound (POCUS) in the diagnosis of lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis.” The Journal of emergency medicine 54.5 (2018): 656-664.

- Hull R, Hirsh J, Sackett DL, et al. Clinical validity of a negative venogram in patients with clinically suspected venous thrombosis. Circulation 1981; 64:622.

- Gorman WP, Davis KR, Donnelly R. ABC of arterial and venous disease. Swollen lower limb-1: general assessment and deep vein thrombosis. BMJ 2000; 320:1453.

- Chiesa R, Marone EM, Limoni C, et al. Chronic venous disorders: correlation between visible signs, symptoms, and presence of functional disease. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46:322.

- Executive Committee of the International Society of Lymphology. The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2020 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 2020; 53:3.

- Marinus J, Moseley GL, Birklein F, et al. Clinical features and pathophysiology of complex regional pain syndrome. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10:637.

- Blankfield RP, Finkelhor RS, Alexander JJ, et al. Etiology and diagnosis of bilateral leg edema in primary care. Am J Med 1998; 105:192.