Lower limb swelling, or edema, is a frequent complaint, particularly among older adults and those with chronic health conditions. This article provides a detailed overview of bilateral lower limb swelling, focusing on its potential causes, diagnostic approach, and initial management strategies relevant for healthcare professionals. Understanding the differential diagnosis of bilateral lower limb swelling is crucial for timely and effective patient care.

Understanding Oedema

Oedema, clinically recognized as palpable swelling, arises from an abnormal accumulation of fluid within the interstitial spaces of tissues. [1] It can manifest in two primary forms: generalized oedema, affecting widespread areas of the body, or localized oedema, confined to a specific body part. In individuals who are mobile and spend considerable time standing, dependent oedema, a type of localized swelling, is particularly common due to gravity-related fluid accumulation in the lower limbs.

Box 1: Common Causes of Oedema

| Generalised Oedema | Localised Oedema |

|---|---|

| • Anaphylaxis | • Infection |

| • Chronic Liver Disease/Cirrhosis | • Inflammation (Gout, Pseudo-gout) |

| • Chronic Kidney Disease/Nephrotic Syndrome | • Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) |

| • Heart Failure | • Venous Insufficiency |

| • Protein-Losing Enteropathy | • Lymphoedema |

| • Hypothyroidism | • Dependent Oedema |

| • Pregnancy | |

| • Medications: | |

| – Dihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blockers (e.g., Amlodipine) | |

| – Steroids | |

| – Oestrogens and Progestins | |

| – NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) | |

| – Vasodilators (Hydralazine, Minoxidil, Diazoxide) | |

| – Thiazolidinediones | |

| – Traditional Medications (Potential Steroid Content) |

Clinical Significance of Lower Limb Oedema

Lower limb oedema is a prevalent presentation in clinical practice, especially among general practitioners and those managing older populations with pre-existing chronic illnesses. It is essential to recognize that lower limb oedema can be an early indicator of a serious underlying systemic disease. Prompt identification and appropriate referral to specialists when needed can significantly improve patient outcomes by facilitating timely treatment and potentially reducing morbidity and mortality.

Initial Assessment in Primary Care

When evaluating a patient presenting with lower limb oedema, the first crucial step is to determine the urgency of the situation. Assess whether the patient can be safely managed in an outpatient setting or requires immediate hospital referral. Patients exhibiting haemodynamic instability, such as hypotension or tachycardia, or signs of respiratory distress like tachypnoea, should be urgently directed to the emergency department for immediate evaluation and care.

For clinically stable patients, a general practitioner can proceed with a focused history taking and physical examination. A key initial step is to differentiate between unilateral and bilateral oedema. This distinction is critical as it significantly narrows the differential diagnoses. Unilateral oedema is often indicative of localized pathology such as infection or deep vein thrombosis in a single limb. Conversely, bilateral oedema typically suggests a systemic aetiology, such as heart failure, kidney disease, or liver dysfunction.

Diagnostic Approach to Bilateral Lower Limb Oedema

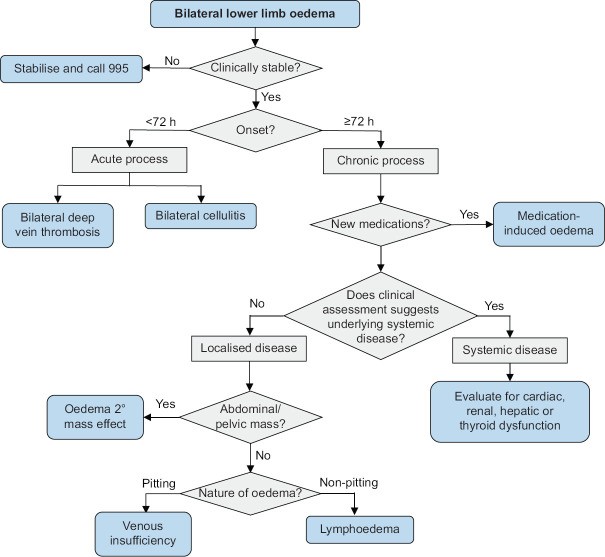

This discussion will primarily focus on the diagnostic approach to bilateral lower limb oedema. Figure 1 outlines a suggested algorithm for evaluating patients with this condition.

Figure 1: Diagnostic Algorithm for Bilateral Lower Limb Oedema

Diagnostic algorithm for bilateral lower limb oedema.

Diagnostic algorithm for bilateral lower limb oedema.

Diagnostic algorithm for evaluating bilateral lower limb oedema, guiding clinicians through history, examination, and investigations to determine the underlying cause.

History and Physical Examination

A detailed history is paramount in evaluating bilateral lower limb oedema. Key aspects to establish include the onset, duration, and progression of the swelling. Many patients report a gradual onset of swelling over weeks or months, typically worsening after prolonged standing. Atypical presentations, such as rapid onset oedema (within 72 hours), should raise suspicion for conditions like infection or bilateral deep vein thrombosis. Oedema that does not worsen with standing may suggest alternative diagnoses such as myxoedema associated with hypothyroidism.

Medication history is critical. It is essential to ascertain the temporal relationship between the onset of swelling and the initiation of any new medications. Drug-induced oedema often develops gradually, typically weeks to months after starting a new medication. [2] Calcium channel blockers (CCBs), particularly dihydropyridine types like amlodipine, nifedipine, and felodipine, are notorious for causing lower limb oedema in approximately 10% of patients. [2] The risk of CCB-induced oedema is dose-dependent and more pronounced with dihydropyridine CCBs compared to non-dihydropyridine CCBs such as diltiazem and verapamil. [2]

Following the characterization of the swelling, the clinical assessment should focus on identifying signs and symptoms suggestive of underlying systemic disorders. Bilateral lower limb oedema frequently results from cardiac, renal, hepatic, or thyroid dysfunction. Therefore, assessing for symptoms and signs related to these organ systems is crucial [Table 1].

Table 1: Key Symptoms and Signs Associated with Systemic Disorders

| Disorder | Symptom/Sign |

|---|---|

| Heart Failure [3, 4] | • Orthopnoea (Shortness of breath when lying flat) |

| • Paroxysmal Nocturnal Dyspnoea (Sudden nighttime breathlessness) | |

| • Exertional Dyspnoea (Shortness of breath on exertion) | |

| • Reduced Exercise Tolerance | |

| • Third Heart Sound (S3 Gallop) | |

| Chronic Liver Disease [5] | • Ascites (Abdominal fluid accumulation) |

| • Scleral Icterus (Yellowing of the sclera of the eyes) | |

| • Spider Naevi (Spider-like blood vessels on skin) | |

| • Palmar Erythema (Redness of the palms) | |

| • Reduced Axillary Hair | |

| • Testicular Atrophy | |

| • Distended Abdominal Veins (Caput Medusae) | |

| Hypothyroidism [6, 7] | • Constipation |

| • Cold Intolerance | |

| • Bradycardia (Slow heart rate) | |

| • Delayed Deep Tendon Reflexes | |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | • No highly sensitive specific symptom or sign – diagnosis relies more on laboratory tests |

A careful physical examination should include palpation for inguinal lymphadenopathy and abdominal examination to detect any masses. Pelvic or abdominal masses can contribute to lower limb swelling by obstructing venous and lymphatic drainage.

In the absence of systemic symptoms, signs, or medications known to induce oedema, localized pathologies such as chronic venous insufficiency or lymphoedema become more probable. Physical examination helps differentiate these conditions. Chronic venous insufficiency oedema is typically pitting, meaning pressure applied to the swollen area leaves a persistent indentation. In contrast, lymphoedema is often non-pitting. Skin changes also provide clues. Chronic venous insufficiency may present with hyperpigmentation in the gaiter area (lower leg), stasis eczema, varicose veins, telangiectasias (spider veins), and venous ulcers. Lymphoedema skin changes, when present, may include a cobblestone or verrucous appearance and a thickened, doughy texture upon palpation.

Initial Investigations

Prior to ordering new investigations, reviewing the patient’s electronic health records for existing relevant test results is advisable. Look for previous serum creatinine, liver function tests, urine protein/albumin, echocardiograms, and venous reflux studies. If recent tests are unavailable or indicated based on clinical suspicion, targeted investigations should be ordered. Routine renal panel, urine dipstick, liver function, and thyroid function tests are not necessary for all patients but should be considered based on clinical findings suggestive of organ dysfunction.

Initial Management Strategies

General practitioners can initiate several lifestyle interventions to help manage lower limb swelling. Advise patients to take regular breaks from prolonged sitting or standing (over 1 hour) by elevating their legs, engaging in brisk walking, or performing calf raises for about 10 minutes. Manual lymphatic drainage through gentle massage towards the heart and leg elevation with pillows during sleep can also be beneficial.

If medication-induced oedema is suspected, consider reducing the dose of the offending drug or switching to an alternative medication class. A follow-up appointment should be scheduled to assess for oedema resolution.

For patients with suspected fluid overload due to heart failure, kidney disease, or liver disease, specialist referral should be considered. Initiating fluid restriction is also reasonable, with guidelines suggesting an initial target of 1.5 litres per day. [8] A practical approach is to advise patients to limit their fluid intake to a standard 1.5-litre bottle per day, accounting for fluid content in foods like soups and desserts. Moderating salt intake and daily weight monitoring at home are also recommended.

For chronic venous insufficiency, graduated compression stockings are the primary treatment. For patients with varicose veins and oedema, a compression level of 20–30 mmHg is generally recommended. [9] These stockings are widely available at pharmacies. Good skin care is crucial to prevent complications like venous stasis eczema and ulcers. Gentle skin care practices are important; advise patients to use mild, fragrance-free soap substitutes like emulsifying ointment or aqueous cream instead of harsh soaps that can dry the skin. After bathing, pat the skin dry gently and apply an emollient to damp skin within 2 minutes to lock in moisture, reapplying as needed to maintain skin hydration. Patients with severe venous insufficiency symptoms or complications like venous ulcers should be referred to a vascular surgeon. [9]

In cases where lower limb swelling causes significant discomfort or interferes with daily activities, a loop diuretic such as furosemide (frusemide) can be considered. The typical starting oral dose is 20 mg once daily. [8] It is important to be aware that furosemide is a potent diuretic and can lead to electrolyte imbalances, dehydration, and pre-renal acute kidney injury. Therefore, electrolyte levels (particularly sodium and potassium) and renal function should be closely monitored after starting furosemide. While specific guidelines on monitoring frequency are lacking, most clinicians would check these parameters within 1–2 weeks of initiation. Patients should also be educated about symptoms of overdiuresis, such as excessive thirst, increased lethargy, or confusion.

When to Refer to a Specialist

Specialist referral is indicated when organ failure is suspected, disease complications necessitate advanced intervention, or the underlying cause of oedema remains unclear after initial assessment. Specific referral criteria include: suspected heart failure, chronic kidney disease (stage 3 or higher), liver cirrhosis, chronic venous insufficiency with severe symptoms or ulcers, recurrent fluid overload, and diagnostically uncertain cases.

Patients who are clinically unstable (tachypnoeic, hypoxic, hypotensive, or with altered mental status) require immediate referral to the emergency department. Stable patients should be seen by a specialist in a timely manner, ideally within 2–4 weeks.

Key Takeaways

- Lower limb swelling is a common presentation in primary care. A systematic approach, starting with a thorough history and physical examination, is usually sufficient to establish a diagnosis.

- Differentiating between unilateral and bilateral oedema is the initial critical step. Unilateral oedema suggests localized causes, while bilateral oedema is more often linked to systemic conditions.

- Bilateral lower limb oedema is frequently a manifestation of systemic dysfunction involving the cardiac, renal, hepatic, or thyroid systems. Recognizing key symptoms and signs associated with these disorders is crucial.

- A comprehensive review of the patient’s medical history, including medication review, is essential.

- Investigations should be targeted and guided by clinical suspicion rather than routine.

- Initial management includes lifestyle modifications like leg elevation and fluid restriction (around 1.5 L/day).

- For symptomatic relief of significant swelling, consider a loop diuretic, with close monitoring of electrolytes and renal function within the first two weeks.

- Specialist referral is necessary in cases of suspected organ failure, complex complications, or diagnostic uncertainty.

Concluding Case

Consider a patient presenting with bilateral leg swelling, orthopnoea, and exertional dyspnoea. Even if they are taking medications like amlodipine, but have newly developed swelling, suspect conditions like congestive heart failure. Referral to a cardiologist is warranted. Further evaluation, as in the case of Mrs. Tan, might reveal underlying conditions like ischaemic cardiomyopathy requiring specific interventions such as guideline-directed medical therapy and percutaneous coronary intervention, leading to resolution of the leg swelling.

Financial Disclosure

None reported.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Continuing Medical Education (CME) Questions

Link to Online Quiz: https://www.sma.org.sg/cme-programme

Submission Deadline: 6 pm, 09 August 2023

| Question | True | False |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Oedema is defined as palpable swelling due to the accumulation of fluid within the intravascular space. | ||

| 2. In standing and mobile adults, the most common cause of localised oedema is dependent oedema. | ||

| 3. Drugs that can cause oedema include steroids, oestrogens and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. | ||

| 4. All patients with lower limb oedema can be evaluated safely in the outpatient setting. | ||

| 5. Patients who are haemodynamically unstable or visibly tachypnoeic should be referred to the emergency department as soon as possible. | ||

| 6. The swelling seen in medication-induced oedema occurs gradually, with effects usually occurring weeks to months after initiation. | ||

| 7. The oedema associated with calcium channel blockers (CCBs) occurs more frequently with non-dihydropyridine CCBs than with dihydropyridine CCBs. | ||

| 8. The skin in patients with chronic venous insufficiency may take on a cobblestoned, verrucous appearance over time. | ||

| 9. A common cause of bilateral lower limb oedema is hyperthyroidism. | ||

| 10. If a patient reports leg swelling of more rapid onset (over hours to days), there is a low suspicion of bilateral deep vein thrombosis. | ||

| 11. The presence of orthopnoea and shortness of breath on exertion increases the likelihood that lower limb oedema is due to heart failure. | ||

| 12. The presence of palmar erythema and spider naevi decreases the likelihood that lower limb oedema is due to chronic liver disease. | ||

| 13. Intra-abdominal masses can cause lower limb swelling through the compression of veins and/or lymphatics. | ||

| 14. In most cases, the oedema seen in lymphoedema is pitting, while the oedema seen in chronic venous insufficiency is nonpitting. | ||

| 15. A renal function test, thyroid function test and urine dipstick should be routinely ordered for all patients with bilateral lower limb oedema. | ||

| 16. The recommended initial target for fluid restriction is 1.5 L/day for a patient with fluid overload. | ||

| 17. When initiating frusemide, an initial dose of 40 mg twice daily is recommended. | ||

| 18. After starting a patient on frusemide, general practitioners (GPs) should consider monitoring the patient’s renal function and electrolyte levels within 1–2 weeks. | ||

| 19. For patients with venous insufficiency, good skin care is not essential in preventing complications such as venous stasis eczema and ulcers. | ||

| 20. GPs should refer all patients with bilateral lower limb oedema to a specialist. |