Neck swellings, particularly when they occur bilaterally, pose a significant diagnostic challenge in clinical practice. The broad range of potential underlying conditions necessitates a systematic approach to differential diagnosis to ensure accurate and timely management. This article presents a case study highlighting the complexities of bilateral neck swelling diagnosis and discusses the key considerations in differential diagnosis.

Case History: An Elderly Patient with Bilateral Neck Swelling

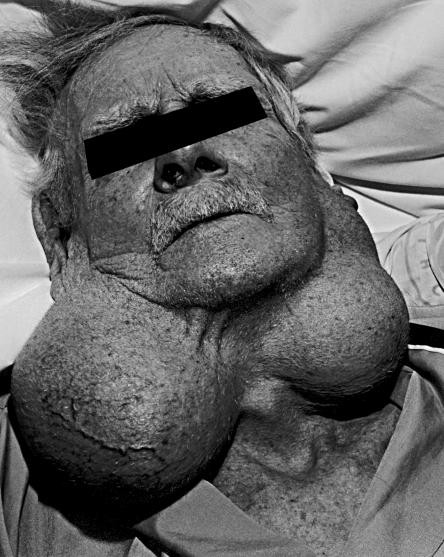

An 81-year-old male, a smoker with a history of recent hospitalization for pneumonia, was evaluated at home for complaints of weight loss, shortness of breath, and generalized weakness. The most prominent finding during the physical examination was a striking, massive swelling on both sides of his neck (Figure 1). Interestingly, the patient reported a 25-year history of right cheek swelling and a 9-year history of left cheek swelling, which had gradually enlarged over the past year but caused minimal discomfort.

On examination, these swellings were cystic, with mild tenderness to palpation on the right side. Attempts at core biopsies of both lesions yielded only purulent fluid. Microbial cultures from this fluid were negative, and cytological analysis revealed no malignant cells, although the samples were poorly cellular.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound imaging of the neck revealed predominantly cystic swellings with uniformly low-level echoes, suggestive of proteinaceous content. A subsequent CT scan of the neck (Figure 2) demonstrated well-defined cystic masses on each side, extending from behind the angle of the mandible down to the level of the hyoid bone. Notably, there was no evidence of cervical lymph node enlargement (adenopathy). At this stage, the neck swellings were considered to be most likely longstanding branchial cysts.

However, further radiological investigations uncovered metastatic disease in the liver originating from a primary bronchogenic carcinoma. Ultrasound also indicated a possible lesion in one kidney. The patient’s clinical condition rapidly declined, and he passed away peacefully in the hospital. A post-mortem examination (necropsy) confirmed the presence of two primary tumors: a poorly differentiated non-small-cell bronchogenic carcinoma with hepatic metastases, and a small renal cell carcinoma. The bilateral neck cysts were indeed confirmed as branchial cysts, measuring 13×9×5 cm on the left and 17×10×8 cm on the right. Microscopic examination of the cyst walls showed abundant lymphoid tissue with a thin squamous epithelial lining and numerous cholesterol clefts.

Figure 2.

Differential Diagnosis of Bilateral Neck Swelling

While branchial cysts were ultimately diagnosed in this case, bilateral neck swelling necessitates a comprehensive differential diagnosis to consider and exclude other potential etiologies. Branchial cysts themselves, although reported in individuals up to 60 years of age, are rarely described bilaterally in older patients. Typically, branchial cysts present in the anterior triangle of the neck, specifically under the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the junction of the upper and middle thirds. They are more common in males, usually on the left side, and typically manifest after the age of 10, with peak incidence in the third decade of life. The fluid within branchial cysts often contains characteristic cholesterol crystals.

The precise origin of branchial cysts remains debated, with several theories proposed. These include the possibility that they are remnants of pharyngeal pouches or branchial clefts, or that they arise from the failure of the cervical sinus to obliterate (the cervical sinus forms when the second branchial arch overgrows the third and fourth). Histologically, most branchial cysts are lined by squamous epithelium and exhibit lymphoid tissue in their walls, leading to the hypothesis that the cyst epithelium may originate from squamous epithelium within lymph nodes.

Establishing the correct diagnosis of bilateral neck swelling requires a detailed patient history and thorough physical examination. Radiological imaging techniques, such as ultrasound and CT scans, along with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and core biopsy, often play crucial roles in narrowing the differential diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for neck swelling includes several key entities:

- Parotid Tumor: Tumors of the parotid gland can present as neck swellings, although they are typically unilateral. Bilateral parotid masses are less common but possible.

- Lymphadenopathy: Enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, due to infection, inflammation, or malignancy, are a frequent cause of neck swelling. Bilateral lymphadenopathy is often associated with systemic conditions.

- Thyroid Disease: Conditions affecting the thyroid gland, such as goiter or thyroid nodules, can cause anterior neck swelling. While often midline, thyroid enlargement can extend laterally and appear bilateral.

- Cystic Hygroma: These congenital lymphatic malformations typically present in children but can persist into adulthood. They are usually located in the posterior triangle of the neck but can extend bilaterally.

- Carotid Body Tumor: These rare tumors of the carotid body, located at the bifurcation of the carotid artery, can present as neck masses. While usually unilateral, bilateral carotid body tumors have been reported, particularly in familial cases.

Ultrasound imaging is particularly useful in evaluating branchial cysts, often demonstrating uniformly low echogenicity, which can help differentiate them from other neck lesions and guide surgical planning. In cases where a parotid mass is suspected, a CT scan is recommended to delineate the extent of the mass and assess for involvement of the deep lobe or the parapharyngeal space. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers superior soft tissue contrast resolution and multiplanar imaging capabilities, providing detailed anatomical information. FNA and cytological examination of the aspirate can be valuable in distinguishing between conditions that may clinically resemble each other, such as cystic nodal metastasis. If FNA is inconclusive or yields a non-diagnostic sample, a core biopsy may be necessary to obtain sufficient tissue for histological diagnosis. The definitive treatment for branchial cysts is surgical excision.

Conclusion

Bilateral neck swelling presents a diagnostic challenge requiring careful consideration of a broad differential diagnosis. This case highlights the importance of thorough clinical evaluation, appropriate radiological investigations, and histopathological examination in reaching a definitive diagnosis. While branchial cysts are a recognized entity in the differential diagnosis of neck swellings, their bilateral presentation, particularly in older adults, is less common and necessitates exclusion of other potential pathologies, including parotid tumors, lymphadenopathy, thyroid disease, cystic hygroma, and carotid body tumors. A systematic approach to diagnosis is crucial for optimal patient management.