INTRODUCTION

Blastocystis spp. is a prevalent enteric protozoan recognized globally as a common cause of gastrointestinal distress. [1] Various morphological forms of Blastocystis spp. are identified, including vacuolar, granular, multivacuolar, amoeboid, and cystic forms. Transmission, similar to other intestinal parasites, is believed to occur via the fecal-oral route, although experimental confirmation is still pending. [2] Accurate blastocystis diagnosis is crucial for effective patient management and understanding its epidemiological impact.

Traditional diagnostic approaches for blastocystis diagnosis have included direct microscopic examination of fecal samples, both with and without Lugol’s iodine stain. Trichrome-stained permanent smears have also been a recommended method for identifying Blastocystis spp. infections. [3] Formalin-ether concentration techniques offer another avenue, particularly advantageous for preserving and concentrating fecal specimens. [4] Earlier studies have indicated that Blastocystis spp. exhibits rapid multiplication in serum-supplemented culture media within 24-48 hours, positioning in vitro cultivation as a highly sensitive diagnostic method. [5]

This study was undertaken to evaluate and identify the most effective direct method for blastocystis diagnosis and to characterize the diverse morphological presentations of this parasite.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

Prior to commencing the study, all participants, or their mothers in the case of children, were informed about the study’s objectives, and oral consent was obtained. The ethical review board of the Faculty of Medicine, Benha University, reviewed and approved the study protocol, ensuring adherence to ethical guidelines.

Study Design

Study Type

This research employed a cross-sectional study design to assess blastocystis diagnosis methods.

Study Setting

The study was conducted across six centers and six villages within the Qualyobia Governorate, Egypt, encompassing both urban and rural populations. Sample examinations were performed at the Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Benha University.

Study Participants

The study group comprised 1200 patients presenting with diarrhea. Among them, 694 (57.8%) were male and 506 (42.2%) were female. These patients were recruited from Ministry of Health hospitals, outpatient clinics, or diagnostic laboratories within the study region. Data was collected on additional gastroenteritis symptoms (vomiting, nausea, abdominal pain, flatulence), skin rashes, joint pain, and immunosuppressive conditions (hepatic or renal illness, steroid use).

Stool samples were collected and analyzed throughout the study period, from April 2012 to December 2013. Each sample was placed in a sterile, disposable plastic container, labeled with patient details: sex, name, age, residence, and collection date.

Laboratory investigations for blastocystis diagnosis included parasitological stool examinations using the following techniques:

Macroscopic Examination

Initial assessment of stool samples involved macroscopic examination to note consistency, color, odor, and the presence of blood or mucus, providing preliminary insights for blastocystis diagnosis and overall sample quality.

Microscopic Stool Examination for Blastocystis Diagnosis

Microscopic examination for blastocystis diagnosis was performed using several methods:

- Direct Wet Mount Smear: [6] This method allows for rapid initial screening for Blastocystis spp. and other parasites in fresh stool samples.

- Iodine-Stained Smear: [7] Iodine staining enhances the visibility of Blastocystis spp. and other protozoan cysts, aiding in blastocystis diagnosis by improving contrast and highlighting internal structures.

- Formol-Ether Concentration Technique: [8] This concentration method is designed to separate parasites from fecal debris, increasing the sensitivity of blastocystis diagnosis by concentrating organisms present in low numbers.

- Modified Trichrome Stain: [9] Trichrome stain is a permanent stain that provides detailed morphological features of Blastocystis spp. and other protozoa, crucial for accurate blastocystis diagnosis and species identification.

- Stool Culture on Jones’ Medium: [10] In vitro cultivation on Jones’ medium is used to enhance the detection of Blastocystis spp., particularly in cases where microscopic methods may yield false negatives, making it a highly sensitive method for blastocystis diagnosis.

Inoculation of Culture Media Procedure

The Jones’ medium was prepared following a specific protocol:

- Dissolve 1.244 g of Na2 HPO4 in 131.25 ml of distilled water.

- Dissolve 0.397 g of KH2 PO4 in 43.75 ml of distilled water.

- Dissolve 7.087 g of NaCl in 787.50 ml of distilled water.

- Mix these solutions to a total volume of 962.5 ml.

- Discard 15.2 ml of the solution (leaving 950 ml).

- Take 100 ml of the solution and add 1 g of yeast extract (leaving 850 ml).

- Add 100 ml of 1% yeast (5.2) back to the 850 ml solution.

- The final volume should reach 950 ml with approximately 0.01% yeast (pH typically 7).

The solution was then aliquoted into 100 ml bottles and autoclaved at 121°C for 15 minutes, then cooled. 10 ml of horse serum was added to 90 ml of the sterile medium. A 5 ml volume of this medium was aliquoted into sterile 7 ml culture tubes using aseptic techniques and stored at 4°C until use. Prior to stool sample inoculation for blastocystis diagnosis, culture medium tubes were warmed in an autoclave at 37°C and incubated at 37°C. On the third day of culture, a drop of sediment was examined microscopically for the presence of Blastocystis spp., confirming blastocystis diagnosis through cultivation.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 16, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Qualitative data were analyzed using frequency and percentage distributions. The Z-test and Chi-square test were employed to compare frequencies and determine statistical significance in blastocystis diagnosis method comparisons.

RESULTS

The comparative analysis of different techniques for blastocystis diagnosis revealed that in vitro culture detected the highest number of positive cases, 274 out of 1200 (22.8%). These variations in detection rates across different methods were statistically significant (P<0.001) [Table 1]. Using trichrome stained smear as the reference standard, in vitro culture demonstrated 100% sensitivity and 88% specificity in blastocystis diagnosis.

Table 1. Techniques Used for Diagnosis of Blastocystis hominis

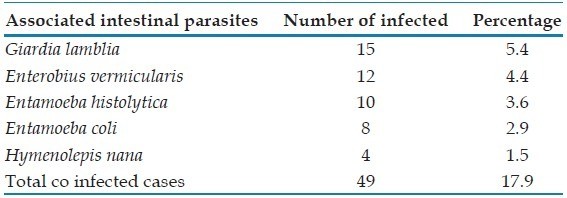

Analysis of mixed infections in blastocystis diagnosis indicated that among the 274 positive cases, 225 (approximately 82%) were mono-infections of Blastocystis spp., while 49 cases (approximately 18%) presented with co-infections of other intestinal parasites. Giardia lamblia was the most frequently co-occurring parasite in Blastocystis spp. infections [Table 2].

Table 2. Mixed Blastocystis hominis Infection and Other Intestinal Parasite

Morphological analysis across all diagnostic methods showed that the vacuolar form was the most prevalent in blastocystis diagnosis, followed by the cyst form, granular form, and amoeboid form, which was exclusively detected in culture [Table 3 and Figures 1–5].

Table 3. Forms of Blastocystis hominis as Recovered by Different Techniques

Figure 1.

Blastocystis spp. after in vitro cultivation using Joni’s medium showing predominance of the vacuolar forms by ×1000 objective

Figure 5.

Cyst form of Blastocystis spp. stained with trichrome by ×1000 objective

Figure 2.

Amoeboid form of Blastocystis spp. in culture stained with iodine by ×1000 objective

Figure 3.

Granular form of Blastocystis spp. in culture by ×1000 objective

Figure 4.

Vacuolar form of Blastocystis spp. stained with trichrome by ×1000 objective

The primary clinical symptom reported by patients diagnosed with blastocystosis was abdominal pain, observed in 265 cases (40.8%), while joint pain was the least common, affecting only 2 cases (5.9%) [Table 4].

Table 4. Clinical Presentations in Blastocystosis Patients

Assessment of diarrhea severity in relation to blastocystis diagnosis showed that moderate diarrhea was most prevalent, affecting 169 patients (61.7%), followed by mild diarrhea in 90 patients (32.8%), and severe diarrhea in 15 patients (5.5%). These differences in diarrhea severity among blastocystosis patients were statistically significant (Chi-square test = 72.01, P<0.001) [Table 5].

Table 5. Severity of Diarrhea Among Blastocystosis Patients

Table 6. Frequency of Clinical Presentation of the Patients

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated various diagnostic techniques for blastocystis diagnosis to determine the most reliable method. Among the 1200 diarrheic stool samples examined, direct microscopy using saline and iodine wet mounts (×40 and ×100 objectives) identified Blastocystis spp. in a limited number of cases. Direct smears detected only 42 positive cases (3.5%), and iodine-stained smears detected 72 (6%). These findings are consistent with previous research [11], which highlighted the challenges in identifying Blastocystis spp. in wet mounts due to its morphological variability.

The formalin-ether concentration technique in this study improved blastocystis diagnosis rates, identifying 120 positive cases (10%). This was a notable increase compared to direct (3.5%) and iodine-stained smears (6%), aligning with reports that concentration techniques enhance detection [12]. However, this contrasts with studies suggesting formalin-ether concentration is unsuitable for Blastocystis spp. detection due to potential parasite disruption [13] and may lead to false negatives [14]. Our results and others [15] indicate that while concentration techniques are useful, they might still have lower sensitivity compared to other methods for blastocystis diagnosis.

Trichrome staining in this study was more effective for blastocystis diagnosis than direct and iodine-stained smears, detecting 148 positive cases (12.3%). This supports conclusions that trichrome stain is more sensitive for intestinal protozoa detection [15]. Some studies equate trichrome stain efficiency to direct examination for Blastocystis spp. confirmation [16], while others, using culture as a gold standard, report even higher sensitivity for both iodine and trichrome stains [16].

Notably, in vitro cultivation using Jones’ medium significantly outperformed all other methods for blastocystis diagnosis in this study. This aligns with studies demonstrating that microscopy post-formalin ether concentration is less effective than in vitro culture for detecting infection [18]. Research in Turkey also showed culture method superiority, identifying significantly more positive cases than Lugol’s iodine and trichrome staining from the same samples [19]. Similarly, a study in Thailand reported higher detection rates with culture methods compared to formalin ethyl acetate concentration techniques [20].

Studies focusing on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients further corroborate these findings. Eida and Eida (2008) found culture more sensitive than microscopy in detecting Blastocystis spp. in IBS patients [21], a conclusion supported by another study that found higher isolation rates through culture compared to microscopic examination in IBS patients [22].

Our finding that in vitro culture detects more Blastocystis spp. cases than trichrome staining aligns with existing literature [23], although some studies note the difference may not always be statistically significant. However, trichrome staining is considerably more time-consuming, making culture a more practical approach for large-scale studies and potentially more sensitive for blastocystis diagnosis. The prevalence of Blastocystis spp. in our study using in vitro cultivation was substantially higher than with simple smears and trichrome staining, reinforcing that culture is more sensitive for blastocystis diagnosis [29]. This increased sensitivity is likely due to the culture medium enhancing parasite size and number, improving detection rates [11].

Morphological analysis revealed the vacuolar form as the most commonly observed across all blastocystis diagnosis methods used in this study. This is consistent with the understanding that the vacuolar form is the typical and most frequently identified form of Blastocystis spp., often considered the primary microbiological evidence for infection [24].

Cyst and granular forms were also detected, with the amoeboid form exclusively found in cultures. The presence of cyst forms in fecal samples, particularly those stored or cultured, has been previously noted [25]. Granular forms are often seen in older cultures [26,27], possibly developing from vacuolar forms due to factors like serum concentration in culture media [28]. The amoeboid form, detected only in culture in our study, is consistent with reports that these forms are primarily observed in culture and may originate from vacuolar forms [29,30]. Epidemiological data also supports the vacuolar form as the most prevalent, followed by granular and then mixed forms [31].

In terms of co-infections, Giardia lamblia was the most frequently associated parasite with Blastocystis hominis in our study, which is in agreement with some reports [5]. However, other studies have indicated Endolimax nana as the most common co-infecting protozoan, followed by G. lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica [32], suggesting geographical or population-specific variations in co-infection patterns.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We extend our gratitude to all members of the Parasitology Lab, Department of Parasitology, Benha Faculty of Medicine, Benha University, for their invaluable assistance in completing this research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

[1] Tan KS. Blastocystis: improving diagnosis, understanding epidemiology and exploring pathogenicity. Trends Parasitol. 2008 Feb;24(2):94-6.

[2] Zierdt CH. Blastocystis hominis–an intestinal protozoan parasite or a harmless commensal? Parasitol Today. 1991 Aug;7(8):199-202.

[3] এল-Dib NS, Abd-Elrahman SH. Blastocystis hominis among children in day care centers in Cairo. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2005 Apr;35(1):209-16.

[4] Allen AV, Ridley DS. Further observations on the formol-ether concentration technique for faecal parasites. J Clin Pathol. 1970 Sep;23(7):545-6.

[5] Ibrahim MA, Farid D, Goka MT, El-Nadi M, Mansour NS, Hassan MM, Rao MR, структуры-Sow SO, Lyke KE, Taylor TE, Levine MM, Kotloff KL. Epidemiology of Blastocystis hominis infection in দূর্বল and healthy children in Egypt. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006 Oct;75(4):648-52.

[6] Garcia LS. Diagnostic medical parasitology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2006.

[7] Beaver PC, Jung RC,