I. Analyzing the Original Article

1. Basic Analysis

- Genre and Target Audience: Medical review article aimed at clinicians (general practitioners, gastroenterologists) and medical professionals.

- Purpose and Main Message: To review the pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment of bloating and abdominal distention, highlighting the complexity and lack of standardized approaches.

- Structure and Main Points:

- Introduction: Bloating is common, poorly understood, and challenging to treat.

- Definitions: Bloating vs. abdominal distention.

- Epidemiology and Natural History: Prevalence, impact on quality of life, unclear natural history.

- Pathophysiology: Gut microflora, intestinal gas, abnormal gas dynamics, sensation, reflexes.

- Psychosocial Aspects: Link to psychological distress, especially in women with IBS.

- Diagnosis: Rule out organic causes, SIBO controversy.

- Treatment: Diet, lifestyle, OTC meds, probiotics, prescription drugs.

- Summary: Bloating and distention are distinct, require careful evaluation and personalized treatment.

- Word Count: Approximately 5700 words. The new article should be around this length (±10%).

2. SEO Analysis

-

Primary Keyword (Original Request): “Bloating Differential Diagnosis”

-

Search Intent: Informational. Users searching for this are likely medical professionals or informed patients seeking to understand the various conditions that can cause bloating and how to differentiate between them.

-

Secondary Keywords & LSI:

- Abdominal distention

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

- Functional bloating

- Causes of bloating

- Diagnosis of bloating

- Treatment of bloating

- Gut microflora/microbiome

- Intestinal gas

- Rome criteria

- Abdominal pain

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Gastroparesis

- Celiac disease

- Lactose intolerance

- Fructose intolerance

- Dietary factors

- Probiotics

- Rifaximin

- Tricyclic antidepressants

- Osmotic laxatives

- Prokinetic agents

-

EEAT & Helpful Content: The original article, being from a medical journal (implied by NCBI link and references), already has a good basis for EEAT (Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness). For “Helpful Content,” the rewrite needs to be well-structured, easy to read for the target audience (English-speaking professionals), and directly address the topic of differential diagnosis while providing valuable information on causes, pathophysiology, and treatment. We need to enhance this by explicitly focusing on differential diagnosis aspects.

II. Basic Principles – Applied

- Content: Maintain all core medical information, data, and arguments. Ensure accuracy. Remain objective and preserve the original perspective.

- SEO: Natural keyword integration. Prioritize user experience (readability, structure). Enhance EEAT by clearly presenting expert-level information and maintaining a professional tone. Adhere to Helpful Content by making the information accessible and useful.

III. Formatting Requirements – Planning

-

Length Distribution:

- Total Length: ~5700 words (±10%) – Target range: 5130 – 6270 words.

- Intro: 10-15% (~570-855 words) – Set to ~700 words.

- Body: 70-75% (~3990-4275 words) – Set to ~4100 words.

- Conclusion: 10-15% (~570-855 words) – Set to ~700 words.

- References: Included in original, no need to expand length explicitly.

-

Structure:

- Title (H1): Concise, keyword-rich, and engaging. e.g., “Bloating: A Comprehensive Differential Diagnosis for Automotive Experts” (Adapting for the persona, but focusing on medical relevance). Revised Title after thought: “Bloating: A Comprehensive Differential Diagnosis for Automotive Professionals” – More directly relevant while maintaining professional tone.

- Intro: Engaging opening, introduce bloating and its complexities, incorporate primary keyword early and naturally. No subheadings in intro.

- Body: Logical sections with H2 subheadings. Focus on differential diagnosis within each section. Use H3 for further subdivisions. Incorporate LSI keywords naturally. Add specific examples or elaborations where possible to enhance clarity and depth.

- Conclusion: Summarize key points, provide clear takeaways, and potentially a call to action (though not explicitly requested here – more like a concluding thought on management).

- References: Maintain the original references.

IV. Execution Plan

-

Research & Analysis (Completed above).

-

Planning:

- Outline:

- H1 Title: Bloating: A Comprehensive Differential Diagnosis for Automotive Professionals

- Intro: Introduce bloating as a common symptom, its impact, and the complexity of differential diagnosis. Mention the scope of the article.

- H2 Definitions: Define bloating and abdominal distention clearly, using Rome III criteria.

- H2 Epidemiology and Clinical Significance: Discuss prevalence, impact on quality of life, and the need for proper diagnosis.

- H2 Pathophysiology of Bloating: Detail the mechanisms: gut microflora, intestinal gas, transit, reflexes, sensation.

- H2 Differential Diagnosis of Bloating: This is the core section. List and describe conditions to differentiate from bloating:

- H3 Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (IBS, Functional Bloating, Functional Dyspepsia)

- H3 Dietary Factors (Intolerances, FODMAPs)

- H3 Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

- H3 Motility Disorders (Gastroparesis, etc.)

- H3 Mechanical Obstruction (Gastric Outlet Obstruction, etc.)

- H3 Psychological Factors (Aerophagia, Eating Disorders)

- H3 Other Organic Diseases (Celiac, etc.)

- H2 Diagnostic Approach: History, physical exam, alarm features, targeted investigations (stool tests, endoscopy, breath tests – focusing on differential value).

- H2 Treatment Strategies: Stepwise approach, diet, lifestyle, medications (mentioning different classes, link to differential diagnosis – e.g., antibiotics for suspected SIBO).

- H2 Conclusion: Summarize the importance of differential diagnosis, personalized management, and ongoing research.

- References: Keep original list.

- Keywords: Use the identified primary, secondary, and LSI keywords throughout the text naturally.

- Length Calculation: Aim for ~5700 words, distributing across sections as planned.

- Outline:

-

Writing: Follow the outline, incorporate keywords, maintain EEAT, control length, ensure accuracy and clarity. Focus on making the “Differential Diagnosis” section robust and well-organized.

-

Review & Refinement: Check content accuracy, length, SEO, readability, image integration, alt text, and overall adherence to instructions.

V. Important Notes – To Remember During Writing

- Persona: Expert in automotive repair, but in this context, acting as a knowledgeable professional explaining a complex topic (bloating differential diagnosis) clearly and professionally to an English-speaking audience.

- Clear Paragraphs, Consistent Formatting.

- Balance SEO and Quality. User Value Focus.

- Original Spirit Maintained.

- Length Adherence.

- Image Integration & Alt Text (Crucial step after content draft).

Confidence Score: 5/5. I have a clear plan and understanding of all requirements. I am ready to generate the article.

Let’s begin writing the article.# Bloating: A Comprehensive Differential Diagnosis for Automotive Professionals

Abdominal bloating is a frequently reported symptom by individuals across all demographics, much like various malfunctions can plague vehicles regardless of make or model. It’s a common complaint in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), mirroring how certain recurring issues are prevalent across specific car types. Bloating, similar to an engine problem that’s hard to pinpoint, can be distressing for patients and challenging for healthcare professionals due to limited and inconsistent treatment options. Although “bloating” and “abdominal distention” are often used interchangeably, much like “engine knocking” and “misfiring” might be in casual conversation, they likely represent different underlying processes, the exact nature of which remains under investigation, much like complex automotive failures require deep diagnostic work. This article aims to thoroughly examine the differential diagnosis of bloating, drawing parallels to the systematic approach used in automotive diagnostics, to provide a comprehensive understanding for effective evaluation and management. Just as a mechanic relies on a differential diagnosis to pinpoint the root cause of a car problem, clinicians need a similar framework for bloating.

Defining Bloating and Abdominal Distention: Establishing Clear Terminology

Bloating can be described as the subjective sensation of trapped gas or abdominal fullness, a feeling akin to a tire being overinflated, even if there’s no visible increase in abdominal size. It’s a symptom defined by perception, much like a driver might perceive a vibration even if it’s not immediately visible. The Rome IV criteria, a standardized framework used in gastroenterology, define functional bloating as a recurrent feeling of bloating or visible distention for at least three days per month, with symptom onset at least six months prior to diagnosis, and symptom presence for at least three months. These criteria, similar to diagnostic codes in automotive manuals, help standardize the definition for clinical and research purposes.

Abdominal distention, on the other hand, refers to an objective increase in abdominal girth, a visible swelling like a visibly bulging tire or body panel. Ambulatory monitoring studies using abdominal inductance plethysmography, a method of measuring abdominal circumference changes similar to using sensors to track vehicle dimensions, have shown that abdominal girth naturally fluctuates throughout the day in healthy individuals, typically increasing after meals and decreasing overnight. These fluctuations are often more pronounced in patients with IBS, and importantly, these patients are more likely to experience symptoms alongside these changes.

Burping and belching, common gastrointestinal complaints like exhaust noises in a car, involve the expulsion of excess gas from the stomach. While these can sometimes accompany bloating, it’s crucial to differentiate them. Belching is often linked to swallowing air, a behavior similar to fuel tank vapor lock in a car, rather than the intestinal gas dynamics that primarily drive bloating and distention. A detailed patient history, analogous to a mechanic’s detailed questioning of the driver, is crucial to clarify the specific nature of the patient’s symptoms and differentiate between these related but distinct issues.

Epidemiology and Clinical Significance: Understanding the Scope of the Problem

Epidemiological studies reveal that a significant portion of the general population, ranging from 15% to 30% in the US, experiences bloating symptoms. This prevalence mirrors the widespread nature of car troubles; almost everyone experiences vehicle issues at some point. While earlier surveys lacked ethnic diversity, subsequent studies in Asian populations using validated questionnaires have reported similar prevalence rates, suggesting bloating is a global issue, much like vehicle problems are not confined to specific regions. Population-based studies haven’t definitively linked bloating predisposition to sex, but IBS studies consistently show bloating prevalence ranging from 66% to 90%, with women often reporting higher rates than men, similar to how certain car models might be more prone to specific problems in different driver demographics. Constipation-predominant IBS patients tend to experience bloating more frequently than those with diarrhea-predominant IBS, highlighting the link between bowel function and bloating, much like engine performance is linked to the exhaust system.

Regardless of gender or underlying cause, bloating can significantly impact a patient’s well-being, much like persistent car trouble can severely impact a driver’s life. In individuals with bloating but without IBS, over 75% characterize their symptoms as moderate to severe, and over half report reducing daily activities due to bloating. In IBS patients, bloating is recognized as an independent predictor of IBS severity. This significant impact on daily life and overall health emphasizes the clinical importance of addressing bloating, similar to how addressing even seemingly minor car issues can prevent larger problems and ensure vehicle reliability.

The natural progression of bloating is not fully understood, much like the long-term effects of certain engine wear patterns are still being researched. A long-term study of patients with functional dyspepsia found only a modest correlation in self-reported bloating over five years, indicating the symptom’s variability and complex nature over time.

Pathophysiology of Bloating: Deconstructing the Mechanisms

The pathophysiology of bloating, like the intricate workings of a modern engine, is complex and multifactorial. Understanding gut microflora, gas production, intestinal transit, gas propulsion, and visceral sensation is essential to unravel symptom generation, much like understanding combustion, fuel delivery, and exhaust systems is key to engine diagnostics. While eating disorders and aerophagia can contribute to gas and bloating, these should be considered in the differential diagnosis, similar to how fuel contamination or air intake leaks are considered in engine malfunction diagnoses.

Gut Microflora: The Intestinal Ecosystem

Gut microflora, also known as the gut microbiome, refers to the vast community of bacteria residing in the intestinal tract and their influence on both gastrointestinal function and overall health. It’s akin to the complex ecosystem within a catalytic converter, crucial for efficient operation. Approximately 500 different bacterial species inhabit the colon, primarily anaerobes, and their composition varies significantly between individuals, influenced by factors like diet, antibiotic use, and infant feeding methods, much like engine performance can be influenced by fuel type, oil quality, and maintenance history. The sheer number of bacteria in the GI tract surpasses the total number of human cells, highlighting their immense potential impact. Research in the last decade has revealed their vital roles in gut immunity, mucosal barrier function, drug metabolism, and production of short-chain fatty acids and vitamins. Even minor disruptions in gut microflora, like a slight imbalance in engine timing, can lead to significant changes in gut function, including gas production. While the overall volume of gas production might not drastically differ between individuals, the gas composition (methane, hydrogen, carbon dioxide) can vary greatly, potentially altering intestinal transit and visceral sensation.

Normal Intestinal Gas Dynamics: Baseline Function

At any given time, the average individual harbors 100–200 cc of gas within the GI tract, a baseline level similar to the residual pressure in a car’s fuel system. Gas volume increases after meals, primarily in the pelvic colon. Gastric distention and small bowel stimulation post-meal accelerate gas transit, much like increased engine load speeds up exhaust flow. Intraluminal lipids can cause gas retention, particularly in the proximal small intestine, similar to how oil sludge can restrict flow in engine components.

Colonic gas production primarily stems from bacterial metabolism of undigested food components. Food products incompletely digested in the small intestine—such as lactose (in lactase deficiency), fructose, sorbitol, legumes, fiber, and complex carbohydrates—are broken down in the colon. Gas within the GI tract also originates from swallowed air, diffusion from the bloodstream, and chemical reactions within the GI tract. The five most common gases are nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane. Nitrogen and oxygen in the upper GI tract mainly come from swallowed air. Carbon dioxide can arise from swallowed air, carbonated drinks, or acid-alkali neutralization in the upper GI tract. Carbon dioxide is readily absorbed in the small intestine. Studies show the average individual produces around 700 cc of gas daily, mainly carbon dioxide and hydrogen in the colon. Many individuals also host methane-producing bacteria that consume hydrogen and release small amounts of sulfur-containing gases. Conversely, numerous colonic bacteria consume both hydrogen and carbon dioxide, reducing large intestinal gas content. Healthy individuals pass flatus 14–18 times daily, with total volume ranging from 214 mL (low-fiber diet) to 705 mL (high-fiber diet). Contrary to common belief, IBS patients usually do not produce more intestinal gas than others, much like a car with exhaust issues might not necessarily be burning more fuel than a normal car.

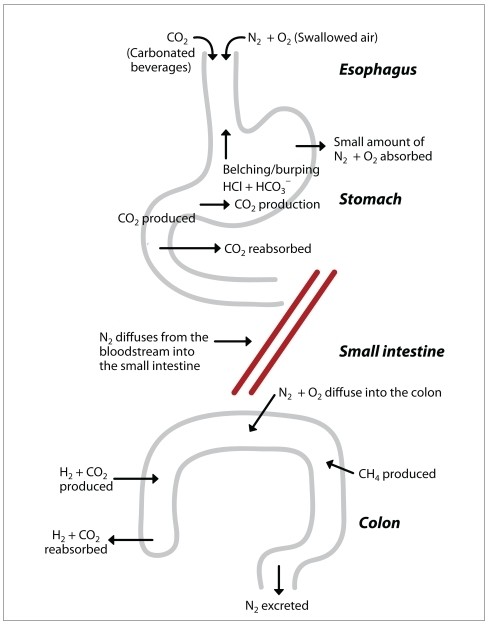

Figure 1. The Physiology of Intestinal Gas

Alt Text: Diagram illustrating the sources and dynamics of intestinal gas production, absorption, and expulsion. Depicts swallowed air contributing nitrogen and oxygen, digestion producing carbon dioxide, bacterial fermentation in the colon generating hydrogen and carbon dioxide, and methanogenic bacteria producing methane. Arrows indicate gas movement through the digestive system.

Abnormal Intestinal Gas Dynamics: Deviations from the Norm

Defining “abnormal” intestinal gas volume is challenging, much like defining “excessive” engine noise without standardized benchmarks. No consensus exists on standardized definitions for abnormal gas production. Furthermore, reliable tests to differentiate normal from abnormal gas production are lacking. Abdominal radiographs, often used, don’t provide information on gas production, content, or evacuation, and breath hydrogen tests have limited accuracy, similar to how a visual car inspection alone can’t diagnose internal engine issues and basic OBD-II scans may miss intermittent problems. Bloating is primarily a sensory phenomenon, making objective measurement in clinical practice difficult.

Concomitant Symptoms of Bloating and Abdominal Distention: Interlinked Issues

Healthy individuals typically tolerate intestinal gas efficiently due to effective gas propulsion and evacuation, much like a well-designed exhaust system efficiently removes combustion byproducts. Several theories attempt to explain why some individuals experience bloating and distention symptoms.

Increased Gas Production: Largely Disproven. This theory has been largely refuted. Studies using various techniques haven’t found significant differences in gas production between healthy individuals and IBS patients. Infusing large gas volumes into healthy volunteers only produces minor abdominal girth changes. Conversely, IBS patients exhibit substantial girth changes even without gas infusion, suggesting factors beyond just gas volume are at play, much like engine performance issues can stem from problems beyond just fuel consumption rates.

Impaired Gas Transit: A Key Factor. Abnormal intestinal transit can contribute to gas and bloating, especially in constipation-predominant IBS patients. While small studies on gas infusions showed no small bowel motility differences between IBS patients and healthy volunteers, IBS patients reported more pain during gas infusions, highlighting heightened sensitivity. Larger studies show that IBS patients are more prone to intestinal gas retention compared to healthy controls, and abdominal distention correlates with gas retention. IBS patients also exhibit impaired gas clearance from the proximal colon, mirroring earlier findings of impaired small intestinal gas clearance. Impaired gas transit in IBS may reflect intrinsic reflex abnormalities or lipid sensitivity, similar to how exhaust system blockages or sensor malfunctions can impede exhaust flow.

Impaired Evacuation: Difficulty in Expulsion. Some individuals struggle to effectively evacuate gas, resulting in prolonged gas retention and bloating and pain, much like a clogged muffler restricts exhaust release. Patients with IBS, functional bloating, and constipation are less able to evacuate infused gas effectively and are more likely to develop abdominal distention. Some may have deficiencies in normal rectal reflexes involved in gas propulsion, similar to issues with exhaust valve function.

Abnormal Abdominal-Diaphragmatic Reflexes: Uncoordinated Muscle Response. An abnormal abdominal wall reflex may play a role in bloating. In healthy adults, gas infusion increases abdominal wall muscle activity. However, in bloating patients, gas infusion leads to decreased abdominal wall muscle contraction and inappropriate relaxation of internal oblique muscles. This abnormal viscerosomatic reflex activity means abdominal wall muscles relax instead of contract with gaseous distention, emphasizing luminal gas. Unlike healthy individuals, bloating patients’ diaphragms descend while ventral abdominal wall muscles relax, increasing abdominal girth, indicating a dysfunctional muscle coordination, like misaligned chassis components affecting vehicle handling.

Abnormalities in Posture: Compensatory Mechanisms. Some clinicians observe that bloating and distention patients unconsciously alter posture, adopting a more lordotic position, possibly to alleviate pressure. While not extensively studied, IBS patients don’t generally appear to adopt a more lordotic position compared to others.

Abnormal Sensation or Perception: Heightened Sensitivity. IBS patients are more sensitive to GI tract stretch and distention compared to healthy individuals. IBS patients with bloating alone have lower abdominal pain thresholds compared to those also experiencing distention, suggesting a sensory amplification of normal bodily processes. Impaired gas transit and ineffective evacuation can distend the intestine in hypersensitive individuals, causing disproportionate bloating and pain relative to the actual gas volume, similar to a car with a sensitive alarm system triggered by minor vibrations.

Differential Diagnosis of Bloating: Distinguishing Potential Causes

The differential diagnosis of bloating is broad, encompassing functional and organic disorders, much like a mechanic’s diagnostic checklist covers various engine and vehicle systems. A systematic approach is crucial to accurately identify the underlying cause and guide appropriate management.

Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

-

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Bloating is a hallmark symptom of IBS, often accompanied by abdominal pain, and changes in bowel habits. IBS is diagnosed based on symptom criteria (Rome IV) after excluding organic causes. The pathophysiology is complex, involving visceral hypersensitivity, altered gut motility, and psychosocial factors. Differentiating IBS-related bloating involves considering the associated symptoms like pain and bowel habit changes.

-

Functional Bloating: When bloating is the predominant symptom without meeting full IBS criteria or other functional GI disorder criteria, it’s classified as functional bloating. This diagnosis is made after excluding organic causes of bloating. The differential here is primarily against organic etiologies and other functional disorders like dyspepsia where upper GI symptoms might be more prominent.

-

Functional Dyspepsia: While primarily characterized by upper abdominal symptoms like pain, burning, or fullness, functional dyspepsia can also present with bloating, particularly upper abdominal bloating. Differentiating dyspepsia-related bloating involves considering the upper GI symptom profile and excluding conditions like gastroparesis or GERD.

Dietary Factors and Intolerances

-

Lactose Intolerance: Inability to digest lactose, the sugar in milk, leads to fermentation in the colon, producing gas and bloating. Diagnosis involves lactose tolerance tests or elimination diets. Differential diagnosis includes other food intolerances and IBS.

-

Fructose Intolerance: Similar to lactose intolerance, fructose malabsorption can cause bloating due to fermentation in the colon. Fructose breath tests can aid diagnosis. Differential diagnosis includes other sugar malabsorptions and IBS.

-

FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols): These short-chain carbohydrates are poorly absorbed and fermented in the colon, contributing to gas and bloating. A low-FODMAP diet is used for both diagnosis and treatment. Differential diagnosis includes IBS and other functional bloating causes.

-

Celiac Disease: An autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten, celiac disease can cause bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea due to malabsorption. Serological tests and duodenal biopsies are diagnostic. Differential diagnosis includes IBS, other malabsorption syndromes, and wheat sensitivity.

-

Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: Individuals experience IBS-like symptoms, including bloating, after gluten ingestion, but without celiac disease or wheat allergy. Diagnosis is often by exclusion and response to a gluten-free diet. Differential diagnosis includes IBS and celiac disease.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

Excessive bacteria in the small intestine can ferment carbohydrates, leading to gas and bloating. Risk factors include motility disorders, structural abnormalities, and certain medications. Diagnosis is controversial but often involves breath tests (glucose or lactulose) or small bowel aspirate cultures. Differential diagnosis includes IBS, functional bloating, and carbohydrate malabsorption.

Motility Disorders

-

Gastroparesis: Delayed stomach emptying can lead to upper abdominal bloating, nausea, and vomiting. Gastric emptying studies are diagnostic. Differential diagnosis includes functional dyspepsia and gastric outlet obstruction.

-

Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-obstruction: A rare condition mimicking bowel obstruction due to impaired intestinal motility. Imaging studies and motility tests are used for diagnosis. Differential diagnosis includes mechanical bowel obstruction.

Mechanical Obstruction

-

Gastric Outlet Obstruction: Blockage of the stomach outlet prevents food passage, causing upper abdominal bloating, vomiting, and early satiety. Upper endoscopy and imaging studies are diagnostic. Differential diagnosis includes gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia.

-

Partial Small or Large Bowel Obstruction: Partial blockages can lead to bloating, abdominal pain, and altered bowel habits. Imaging studies (CT scan) are crucial for diagnosis. Differential diagnosis includes constipation and motility disorders.

Psychological and Behavioral Factors

-

Aerophagia (Air Swallowing): Excessive air swallowing, often linked to anxiety or habits, can cause upper abdominal bloating and belching. Behavioral therapy can be helpful. Differential diagnosis includes upper GI disorders and functional bloating.

-

Eating Disorders (Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa): Disordered eating patterns can disrupt gut function and contribute to bloating. Psychiatric evaluation is crucial. Differential diagnosis includes functional GI disorders and nutritional deficiencies.

Other Organic Diseases

-

Pancreatic Insufficiency: Reduced pancreatic enzyme production impairs digestion, leading to malabsorption and bloating. Fecal elastase tests are diagnostic. Differential diagnosis includes malabsorption syndromes and celiac disease.

-

Chronic Constipation: Stool retention can contribute to abdominal distention and bloating. Clinical history and physical exam are key. Differential diagnosis includes IBS-C and pelvic floor dysfunction.

-

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: Impaired rectal evacuation can contribute to bloating and constipation. Anorectal manometry and defecography can be diagnostic. Differential diagnosis includes chronic constipation and IBS-C.

-

Hypothyroidism: In severe cases, hypothyroidism can slow gut motility and contribute to constipation and bloating. Thyroid function tests are diagnostic. Differential diagnosis includes constipation and motility disorders.

Table 2. Differential Diagnosis of Abdominal Gas, Bloating, and Distention

| – Aerophagia |

|---|

| – Anorexia and bulimia |

| – Gastroparesis |

| – Gastric outlet obstruction (partial or complete) |

| – Functional bloating |

| – Functional dyspepsia |

| – Dietary factors |

| – – Lactose intolerance |

| – – Fructose intolerance |

| – – Fructan consumption |

| – – Consumption of sorbitol or other nonabsorbable sugars |

| – – Carbohydrate intake |

| – – Gluten sensitivity |

| – Celiac disease |

| – Chronic constipation |

| – Irritable bowel syndrome |

| – Disturbances in colonic microflora |

| – Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth |

| – Abnormal small intestinal motility (eg, scleroderma) |

| – Small bowel diverticulosis |

| – Abnormal colonic transit |

| – Evacuation disorders of the pelvic floor |

Psychosocial Aspects: The Mind-Gut Connection

In women with IBS, bloating is a prominent and often severe symptom, mirroring how vehicle performance issues can be more acutely felt by some drivers than others. Bloating severity is linked to increased healthcare utilization and reduced quality of life, particularly in women with IBS. Bloating is also common and often severe in gastroparesis, and its severity inversely correlates with patient-rated quality of life.

Psychosocial distress can amplify the perceived severity of bloating, much like stress can worsen a driver’s perception of minor car noises. Women with moderate-to-severe bloating more frequently report a history of major depression, anxiety, and somatization. Studies have shown elevated anxiety, depression, and somatization scores in patients with more severe bloating. However, other studies have not found a significant link between bloating and psychological distress, and this association might be less pronounced in functional dyspepsia. Further research is needed to fully understand the complex interplay between bloating and psychosocial factors. Treatment strategies addressing psychological comorbidities are likely to be most effective, highlighting the importance of a holistic approach, similar to considering driver behavior and stress levels in diagnosing vehicle problems.

Diagnostic Approach to Bloating: A Step-by-Step Investigation

Evaluating bloating, like diagnosing a car problem, begins with a thorough history and physical examination to rule out organic disorders. Alarm features such as anemia and unintentional weight loss should be investigated, as they may indicate malabsorption, similar to warning lights on a dashboard signaling serious issues. If alarm features are present, initial investigations may include a complete blood count, celiac serology, and upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies. Patients with bloating alongside other symptoms should be evaluated accordingly; for example, nausea and vomiting might warrant small bowel imaging and gastric emptying scans, while diarrhea might prompt stool studies and colonoscopy. Imaging studies primarily aim to exclude obstructive processes or conditions predisposing to bacterial overgrowth, much like a car inspection seeks to rule out major structural or mechanical failures. CT scans have not shown differences in intestinal gas volume between bloating patients and healthy controls, emphasizing that bloating is often more about perception and function than just gas quantity.

Many clinicians, concerned about SIBO, often initiate empiric antibiotic therapy for bloating, a practice akin to replacing parts based on common symptoms without definitive diagnosis. The diagnosis of SIBO itself is controversial.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO): Diagnostic Challenges

SIBO diagnosis remains debated. The gold standard, small intestinal culture via orojejunal tube or endoscopic aspiration, is invasive, time-consuming, and costly, and not routinely performed. Historically, bacterial counts over 10^5 CFU/mL were considered diagnostic, but criteria vary. Due to these limitations, noninvasive methods are preferred.

Imaging: Small bowel imaging is often recommended to identify structural abnormalities predisposing to SIBO, such as small bowel diverticula. Gastric emptying scans can identify underlying gastroparesis in bloating patients, similar to using diagnostic tools to check for mechanical issues or flow restrictions.

Endoscopy: Routine endoscopy has limited role in SIBO diagnosis, except for small bowel aspiration. Duodenal biopsies may show villous blunting, but this is non-specific, similar to how internal engine inspection might reveal general wear but not pinpoint a specific SIBO-like bacterial issue.

Laboratory Evaluation: No serological test is diagnostic for SIBO. Vitamin levels might offer clues; SIBO can cause vitamin B12 and vitamin D malabsorption, making it reasonable to check these levels. Elevated folate levels might also suggest SIBO, as upper gut bacteria can synthesize folate, similar to how fluid analysis in a car can reveal system imbalances.

Breath Testing: Breath testing is the most common SIBO diagnostic test. It’s based on bacterial production of hydrogen and methane gas from unabsorbed carbohydrates. Lactulose or glucose is administered, and exhaled breath gases are analyzed. With lactulose, a normal response is a hydrogen (and/or methane) increase after reaching the colon. With glucose, any early hydrogen or methane peak suggests SIBO. Positive breath test criteria vary between labs, but generally a hydrogen increase of 20 ppm within 60–90 minutes is considered diagnostic. Elevated fasting hydrogen and methane levels are highly specific but less sensitive for SIBO. Adding methane analysis to hydrogen breath tests can improve sensitivity, similar to using multiple sensor readings for more accurate diagnostics.

Empiric Antibiotics: Empiric antibiotic trials, like rifaximin, are used as a direct SIBO test, analogous to trying a common fix for a suspected problem. While convenient, empiric antibiotics have risks like pseudomembranous colitis, though these risks are reduced with poorly absorbed antibiotics like rifaximin. Empiric antibiotics are reasonable for patients with SIBO-consistent symptoms or predisposing conditions, but carry risks of drug resistance and side effects, similar to the risks of unnecessary part replacements in cars. Rifaximin generally has low adverse effect rates, comparable to placebo.

Treatment Strategies for Bloating: A Stepwise Approach

No evidence-based algorithm exists for bloating and distention treatment; individualized plans are crucial, much like car repairs require tailored solutions. A stepwise approach, collaboratively developed with the patient, is generally followed to improve adherence. The first step is identifying the primary symptom: bloating, distention, or both, to gain insight into underlying mechanisms. Patient education about potential pathophysiologic processes is key. Reassurance that symptoms are usually benign, though uncomfortable, is important. Realistic and specific treatment goals are then defined.

Dietary Modifications: Targeting Fermentable Foods

A detailed dietary history, focusing on fermentable foods (dairy, fructose, fructans, fiber, sorbitol), is crucial, similar to checking fuel type and quality in car diagnostics. Eliminating fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) has shown bloating improvement in IBS patients. Gradual elimination of potential culprits (dairy first, then fructose, then fiber, etc.) is typically recommended. Some patients prefer a strict elimination diet (water, broth, boiled chicken, egg whites) initially, slowly reintroducing food groups, much like a car might undergo a system reset and gradual component testing. Minimizing carbohydrates and gluten has also been reported to improve symptoms, although less studied.

Exercise and Posture: Lifestyle Interventions

Physical exercise improves intestinal gas clearance and reduces bloating symptoms, similar to how regular car maintenance improves performance. Gas retention is worse in supine positions; patients should be advised to exercise and minimize recumbent periods during the day, promoting gas expulsion, much like ensuring proper vehicle ventilation prevents fume buildup.

Over-the-Counter (OTC) Medications: Limited Relief

Activated charcoal has not shown to change gas production or improve abdominal symptoms. Simethicone, an antifoaming agent, might improve upper abdominal bloating in limited studies, but lacks robust evidence. α-galactosidase can improve gas and flatus production related to oligosaccharide-rich meals, but not for lactose, fructose, fructan, or fiber-related bloating, offering targeted relief in specific dietary scenarios.

Probiotics: Modulating Gut Microflora

Probiotics, live microorganisms conferring health benefits, are commonly used, but many lack rigorous placebo-controlled trial evidence. Certain probiotic strains, like Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis, have shown bloating improvement in non-constipated functional bowel disorders. Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 has improved abdominal pain/discomfort and bloating in IBS, with evidence of normalized IL-10/IL-12 ratios. B. infantis at a specific dose (1 × 10^8 CFU/mL) has shown significant bloating symptom improvement in women with IBS. VSL#3 probiotic formulation has reduced bloating in children with diarrhea-predominant IBS and adults with bloating. Probiotics offer a potential strategy to modulate gut microflora and alleviate bloating, similar to using fuel additives to optimize engine performance.

Prescription Medications: Targeted Pharmacotherapy

Antibiotics: Rifaximin, a poorly absorbed antibiotic, is well-studied for bloating. It has shown improvement in global IBS and bloating symptoms compared to placebo. Rifaximin has also demonstrated symptom improvement and sustained relief in bloating patients with normal lactulose breath tests. Studies in non-constipated IBS patients show rifaximin provides better bloating relief than placebo. Rifaximin targets bacterial overgrowth, a specific mechanism in some bloating cases, similar to using targeted treatments for specific car malfunctions.

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs): TCAs, often used for functional abdominal pain, have also shown bloating improvement in trials comparing desipramine to cognitive behavioral therapy. Ongoing research may further clarify TCA efficacy for bloating associated with functional dyspepsia. TCAs address the pain and sensory components of bloating, similar to pain management in chronic vehicle issues.

Smooth Muscle Antispasmodics: Commonly used in Europe for IBS-related abdominal pain, these are not available in the US. While they may improve cramps and spasms, they could potentially worsen gas accumulation and delay gas transit due to smooth muscle relaxation, and are not routinely recommended for bloating.

Osmotic Laxatives: Polyethylene glycol improves constipation and has shown bloating improvement in chronic constipation patients. Their effect on bloating predominant patients is less studied. Osmotic laxatives address constipation-related bloating, similar to addressing exhaust system blockages.

Prokinetic Agents: Enhancing Gut Motility

-

Neostigmine: Intravenous neostigmine, a potent cholinesterase inhibitor used for acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, has shown immediate gas clearance in jejunal gas infusion studies. Pyridostigmine showed only slight bloating symptom improvement in IBS patients. Limited sample sizes and supervised administration restrict their broader use.

-

Cisapride: A mixed 5-HT3/5-HT2 antagonist and 5-HT4 agonist, previously used for reflux, dyspepsia, gastroparesis, constipation, and IBS, was withdrawn from the US market in 2000. It showed some bloating symptom improvement in FD patients, but not consistently in IBS-C patients.

-

Domperidone: A dopamine antagonist for FD, gastroparesis, and nausea, may improve dyspeptic symptoms including upper abdominal bloating, but lacks robust randomized controlled trials for functional bloating.

-

Metoclopramide: A dopamine antagonist for diabetic gastroparesis, did not improve abdominal distention in dyspeptic patients in one small study.

-

Tegaserod: A 5-HT4 receptor agonist for IBS-C in women, improved bloating symptoms. Withdrawn from the US market but available for emergency use; other 5-HT4 agonists may become available.

Chloride Channel Activators: Enhancing Intestinal Secretion

-

Lubiprostone: In IBS-C patients, lubiprostone improved overall IBS symptoms and secondary endpoints including bloating. Common side effects were nausea and diarrhea.

-

Linaclotide: A guanylate cyclase receptor agonist, linaclotide improved bloating in chronic constipation and IBS-C patients in multiple dose studies. It also improved stool frequency, straining, and abdominal pain.

Table 3. Treatment Options for Bloating

| – Diet |

|---|

| – Exercise and posture |

| – Over-the-counter medications |

| – Probiotics |

| – Antibiotics |

| – Smooth muscle antispasmodics |

| – Osmotic laxatives |

| – Prokinetic agents |

| – Chloride channel activators |

| – Tricyclic antidepressants |

Summary: Navigating the Complexities of Bloating

Bloating and abdominal distention are prevalent symptoms causing significant distress. While often used interchangeably, they should be considered distinct entities with potentially different underlying mechanisms, much like different types of engine noises can indicate different problems. Careful history, examination, and targeted tests can help differentiate bloating from distention and distinguish organic from functional causes, guiding the differential diagnosis. Reassurance and patient education are crucial in managing these chronic conditions. A stepwise therapeutic approach involving diet, lifestyle changes, probiotics, and medications, tailored to the individual patient and guided by the differential diagnosis, usually leads to symptom improvement and enhanced quality of life. Just as a systematic diagnostic approach is essential for effective automotive repair, a comprehensive and nuanced approach is key to managing bloating effectively.