Abstract

Bronchiolitis stands as the leading cause for hospital admissions in infants during their first year of life. Globally and across Canada, significant variations exist in its clinical management, often marked by the overuse of unnecessary diagnostic tests and ineffective treatments. This guideline focuses on generally healthy children aged two years and under presenting with bronchiolitis. Bronchiolitis Diagnosis is fundamentally clinical, relying on a detailed medical history and thorough physical examination. In most instances, laboratory investigations offer minimal benefit. As bronchiolitis is typically a self-limiting condition, supportive care at home is usually sufficient. This document outlines high-risk groups for severe bronchiolitis, provides guidelines for hospital admission, and reviews the evidence supporting various therapeutic interventions, culminating in management recommendations. We also address essential monitoring practices and criteria for hospital discharge.

Bronchiolitis, a viral infection affecting the lower respiratory tract, is characterized by the obstruction of small airways. This obstruction arises from acute inflammation, edema, and the death of epithelial cells lining these airways, coupled with increased mucus production. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most frequent culprit behind bronchiolitis cases, but other viruses such as human metapneumovirus (HMPV), influenza, rhinovirus, adenovirus, and parainfluenza can induce similar clinical presentations. Co-infections with multiple viruses are observed in 10% to 30% of hospitalized young children. Initial infection does not guarantee immunity; reinfections are common throughout life, generally becoming milder with each occurrence. In Canada, the RSV season typically spans four to five months, starting between November and January.

Bronchiolitis affects over a third of children within their first two years and is the most prevalent cause of hospitalization in the first year of life. Hospitalization rates have risen over the past three decades from 1% to 3% of all infants. This increase places a substantial financial burden on healthcare systems and highlights the significant morbidity and impact on families associated with bronchiolitis.

Despite the availability of numerous clinical practice guidelines, including the widely referenced 2006 guideline from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), considerable variability persists in diagnostic approaches, monitoring, and management strategies for bronchiolitis. Efforts to standardize bronchiolitis care have demonstrated success in reducing unnecessary diagnostic testing and resource utilization, leading to cost savings and improved patient outcomes. While AAP recommendations have contributed to some reduction in testing and treatments, their widespread adoption remains incomplete.

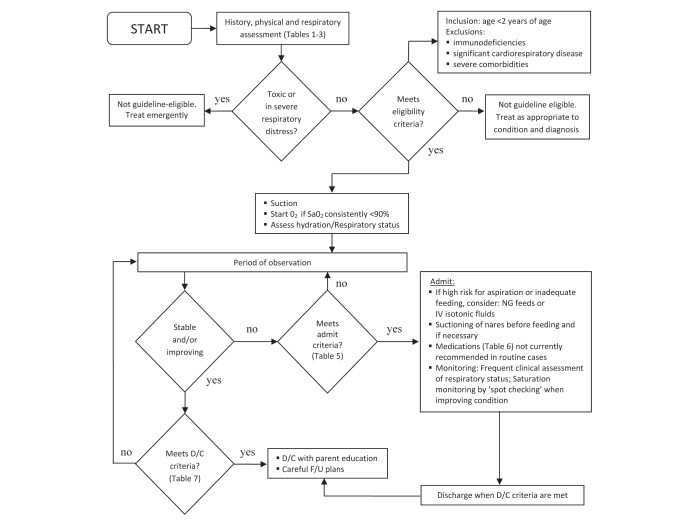

This statement aims to expand upon the comprehensive, peer-reviewed AAP guideline by incorporating new evidence accumulated over the last eight years. It offers clinicians practical recommendations to guide the diagnosis of bronchiolitis, monitoring, and management of previously healthy children aged one to 24 months presenting with bronchiolitis symptoms (Figure 1). The goal is to promote a reduction in the use of superfluous diagnostic procedures and ineffective medications and interventions. This guideline does not apply to children with pre-existing chronic lung disease, immunodeficiency, or other serious chronic conditions. The prevention of bronchiolitis and its potential long-term effects are outside the scope of this document but are extensively discussed in existing literature and other Canadian Paediatric Society statements.

Figure 1: Algorithm for medical management of bronchiolitis. D/C Discharge; F/U Follow-up; IV Intravenous; NG Nasogastric; SaO2 Oxygen saturation. Adapted with permission from reference 12.

DIAGNOSIS OF BRONCHIOLITIS

Bronchiolitis diagnosis is primarily a clinical assessment, grounded in a detailed history and physical examination. The presentation of bronchiolitis can vary widely in symptoms and severity, ranging from a mild upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) to impending respiratory failure (Table 1). Typically, bronchiolitis manifests as a first episode of wheezing before the age of 12 months. The illness usually begins with a viral prodrome lasting two to three days, characterized by fever, cough, and rhinorrhea. This progresses to tachypnea, wheezing, crackles, and varying degrees of respiratory distress. Signs of respiratory distress may include grunting, nasal flaring, indrawing, retractions, or abdominal breathing. A history of exposure to an individual with a viral URTI may or may not be present.

TABLE 1. History, Symptoms and Signs of Viral Bronchiolitis

| Clinical Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Preceding viral upper respiratory tract infection, cough and/or rhinorrhea | Initial symptoms mimicking a common cold |

| Exposure to an individual with viral upper respiratory tract infection | Possible epidemiological link, but not always present |

| Signs of respiratory illness may also include: | |

| – Tachypnea | Increased respiratory rate |

| – Intercostal and/or subcostal retractions | Visible sinking of the skin between or below the ribs during breathing |

| – Accessory muscle use | Use of neck and shoulder muscles to aid breathing |

| – Nasal flaring | Widening of nostrils with each breath |

| – Grunting | Noisy breathing during expiration |

| – Colour change or apnea | Bluish skin discoloration or pauses in breathing |

| – Wheezing or crackles | Abnormal lung sounds heard with a stethoscope |

| – Lower O2 saturations | Reduced oxygen levels in the blood |

Physical examination findings of significant importance include an elevated respiratory rate, signs of respiratory distress, and crackles and wheezing detected during auscultation. Oxygen saturation measurement frequently reveals decreased levels. Dehydration signs might be evident if respiratory distress has significantly interfered with feeding.

While viral bronchiolitis is the most probable diagnosis in infants presenting with acute wheezing between November and April, clinicians should consider a broad differential diagnosis, particularly in cases with atypical presentations. These atypical presentations include severe respiratory distress, absence of viral URTI symptoms, and/or frequent recurrences (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Differential Diagnosis for Wheezing in Young Children

| Differential Diagnosis |

|---|

| Viral bronchiolitis |

| Asthma |

| Other pulmonary infections (e.g., pneumonia) |

| Laryngotracheomalacia |

| Foreign body aspiration |

| Gastroesophageal reflux |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Vascular ring |

| Allergic reaction |

| Cystic fibrosis |

| Mediastinal mass |

| Tracheoesophageal fistula |

Adapted from reference 7.

INVESTIGATIONS IN BRONCHIOLITIS

Diagnostic studies are generally not indicated for most children with bronchiolitis (Table 3). These tests are often unhelpful and can paradoxically lead to unnecessary hospital admissions, further investigations, and the application of ineffective therapies. Evidence-based reviews have consistently shown that diagnostic testing does not improve outcomes in typical bronchiolitis cases. Relying on clinical judgment for bronchiolitis diagnosis is paramount in typical cases.

TABLE 3. Role of Diagnostic Studies in Typical Cases of Bronchiolitis

| Type of Diagnostic Study | Specific Indications |

|---|---|

| Chest radiograph (CXR) | Only if severity or clinical course suggests an alternate diagnosis (Table 2) |

| Nasopharyngeal swabs for respiratory viruses | Only if required for cohorting admitted patients for infection control purposes |

| Complete blood count (CBC) | Generally not helpful in the diagnosis or monitoring of routine cases of bronchiolitis |

| Blood gas analysis | Only if there is concern about potential respiratory failure |

| Bacterial cultures | Not routinely recommended; may be considered based on clinical findings and the infant’s age, especially in very young infants |

Chest Radiograph (CXR): CXR findings in infants with bronchiolitis are often nonspecific, showing patchy hyperinflation and areas of atelectasis. These findings can be misread as consolidation, leading to an increased and inappropriate use of antibiotics. A recent prospective study in infants with typical bronchiolitis found CXR findings inconsistent with bronchiolitis in only two out of 265 infants. Importantly, CXR results did not alter acute management in any case. While routine CXR is not supported by evidence, it should be considered when the bronchiolitis diagnosis is uncertain, the clinical course is not improving as expected, or the severity of the disease raises suspicion for other conditions such as bacterial pneumonia.

Nasopharyngeal Swabs for Respiratory Viruses: From a diagnostic standpoint, nasopharyngeal swabs for respiratory viruses are generally not helpful and do not change management in most bronchiolitis cases. Routine use is not recommended unless necessary for infection control, such as cohorting hospitalized patients. However, the high incidence of co-infection with multiple viruses has even brought this indication into question.

Complete Blood Count (CBC): CBC has not been shown to be useful in predicting serious bacterial infections (SBI) in children with bronchiolitis.

Bacterial Cultures: The incidence of concomitant SBI in febrile infants with bronchiolitis is considered very low, but not negligible. Infants in their first two months of life are at the highest risk of SBI, particularly urinary tract infections. Bacteremia is rare. Due to the low but present risk of SBI in young infants, especially those under 2 months, bacterial cultures might be considered in this age group based on clinical assessment and risk factors.

DECISION TO ADMIT FOR BRONCHIOLITIS

The decision to admit a child to the hospital for bronchiolitis should be based on clinical judgment, taking into account the infant’s respiratory status, ability to maintain adequate hydration, risk of progressing to severe disease, and the family’s capacity to cope at home (Tables 4 and 5). It is important to remember that bronchiolitis symptoms often worsen over the first 72 hours. Clinical scores or individual physical examination findings alone are not reliable predictors of outcomes. While severity scoring systems exist, they are not widely used, and few have demonstrated strong predictive validity. Respiratory rate, subcostal retractions, and oxygen requirements are often the most informative parameters in bronchiolitis severity scores.

TABLE 4. Groups at Higher Risk for Severe Bronchiolitis

| Risk Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Infants born prematurely (<35 weeks gestation) | Premature infants have less developed lungs and immune systems |

| Hemodynamically significant cardiopulmonary disease | Pre-existing heart or lung conditions increase vulnerability |

| Immunodeficiency | Compromised immune systems are less able to fight infection |

TABLE 5. Guidelines for Admission for Bronchiolitis

| Admission Guideline | Description |

|---|---|

| Signs of severe respiratory distress (e.g., indrawing, grunting, RR >70/min) | Indicate significant breathing difficulty |

| Supplemental O2 required to keep saturations >90% | Inability to maintain adequate oxygen levels without support |

| Dehydration or history of poor fluid intake | Respiratory distress can interfere with feeding and hydration |

| Cyanosis or history of apnea | Serious signs of oxygen deprivation or breathing pauses |

| Infant at high risk for severe disease (Table 4) | Pre-existing conditions that increase risk |

| Family unable to cope | Lack of adequate home support for care and monitoring |

Repeated observations over time are crucial due to the fluctuating nature of bronchiolitis. Consistent predictors of hospitalization in outpatient settings include younger age (≤6 months), history of prematurity, and lower oxygen saturation levels. Infants with an oxygen saturation consistently <90% in room air, a respiratory rate >60 breaths/min, and feeding difficulties have a significantly elevated risk of hospitalization.

The role of pulse oximetry in clinical decision-making remains debated. While oxygen saturations <90% are often used as a threshold for oxygen therapy and admission, it is important to recognize that setting arbitrary thresholds influences admission rates. Studies have shown that even a small reduction in saturation threshold from 94% to 92% can significantly increase the likelihood of recommending hospital admission among physicians.

MANAGEMENT OF BRONCHIOLITIS

Bronchiolitis is a self-limiting illness. Most children experience mild disease and can be effectively managed with supportive care at home. For those requiring hospitalization, supportive care remains the cornerstone of treatment. This includes assisted feeding, minimizing handling, gentle nasal suctioning, and oxygen therapy (Table 6). Effective bronchiolitis diagnosis and management aim to minimize interventions and focus on supportive care.

TABLE 6. Treating Bronchiolitis

| Recommended Therapies | Evidence Equivocal Therapies | Not Recommended Therapies |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen | Epinephrine nebulization | Salbutamol (Ventolin) |

| Hydration | Nasal suctioning | Corticosteroids |

| 3% hypertonic saline nebulization | Antibiotics | |

| Combined epinephrine and dexamethasone | Antivirals | |

| Cool mist therapies or therapy with saline aerosol |

THERAPIES RECOMMENDED BASED ON EVIDENCE

Oxygen Therapy

Supplemental oxygen therapy is a primary treatment in hospitalized bronchiolitis patients. Oxygen should be administered if oxygen saturation falls below 90% and titrated to maintain saturations at ≥90%. Oxygen is typically delivered via nasal cannulae, face mask, or head box to minimize handling. High-flow nasal cannula therapy, a newer approach, may be better tolerated and potentially reduce the need for mechanical ventilation, although current evidence on its effectiveness is still limited. Ongoing research is expected to provide clearer guidance on its use in the near future.

Hydration Management

Approximately 30% of hospitalized bronchiolitis patients require some degree of fluid supplementation. Frequent feeds should be encouraged, and breastfeeding should be supported, which may be facilitated by providing supplemental oxygen. Infants with a respiratory rate >60 breaths/min, especially those with nasal congestion, may have an increased risk of aspiration and may not be safe for oral feeding. When supplemental fluids are needed, nasogastric (NG) and intravenous (IV) routes have been found to be equally effective, with no difference in hospital length of stay. NG insertion may be easier and more successful than IV placement. If NG bolus feeds are not tolerated, slow continuous feeds are an alternative. If IV fluids are used, isotonic solutions (0.9% NaCl/5% dextrose) are preferred for maintenance, with regular monitoring of serum sodium levels due to the risk of hyponatremia.

THERAPIES FOR WHICH EVIDENCE IS EQUIVOCAL

Epinephrine (Adrenaline) Nebulization

Some studies suggest that epinephrine nebulization might reduce hospital admissions, and one trial indicated that combined treatment with epinephrine and steroids reduced admissions. However, current evidence is insufficient to support the routine use of epinephrine in the emergency department. Administering a dose of epinephrine and closely monitoring clinical response may be reasonable. Continued use is not recommended unless clear clinical improvement is observed. A systematic review of 19 studies on epinephrine use in bronchiolitis showed no effect on length of hospital stay, and evidence is insufficient to support its routine use in hospitalized patients.

Nasal Suctioning

Despite being a long-standing and common practice, limited evidence supports the effectiveness of nasal suctioning in bronchiolitis management. While removing mucus from blocked nasal passages seems beneficial, a recent study suggested that deep suctioning and infrequent suctioning intervals are associated with increased length of hospital stay. This suggests that if suctioning is performed, it should be superficial and reasonably frequent.

3% Hypertonic Saline Nebulization

The efficacy of nebulized 3% hypertonic saline is actively debated, and definitive recommendations require further research. The proposed mechanism is that hypertonic saline enhances mucociliary clearance and rehydrates airway surface liquid. Evidence suggests reduced clinical severity scores in both inpatient and outpatient settings without significant adverse events. A Cochrane review of 11 trials found that nebulized hypertonic saline was associated with a one-day reduction in hospital stay in settings with longer admissions (>3 days). The optimal treatment regimen remains unclear. The most common regimen in trials has been 3% saline with or without a bronchodilator, administered three times daily via jet nebulizer with 8-hour intervals. Subsequent studies have shown mixed results. Nebulized 3% saline may be beneficial in hospitalized patients, particularly those with longer stays. Current evidence does not support its routine use in outpatient settings.

Combination Epinephrine and Dexamethasone

One study reported a potential synergistic effect of combining nebulized epinephrine with oral dexamethasone, suggesting a reduced hospitalization rate. However, these results were not statistically significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons. Further research is needed to assess the role of combination therapies. Pending better understanding of its risks and benefits, this combination is not recommended for routine bronchiolitis therapy in otherwise healthy children.

THERAPIES NOT RECOMMENDED BASED ON EVIDENCE

Salbutamol (Ventolin)

While bronchiolitis presents with wheezing similar to asthma, the underlying pathophysiology involves airway obstruction rather than constriction. Infants also appear to have fewer β-agonist lung receptor sites and immature bronchiolar smooth muscles. Although studies have shown small improvements in clinical scores, bronchodilators like salbutamol have not been shown to improve oxygen saturation, reduce admission rates, or shorten hospital stay. When bronchiolitis diagnosis is clear, a trial of salbutamol is not currently recommended.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids, including dexamethasone, prednisone, and inhaled glucocorticoids, have not demonstrated clinically significant improvement in bronchiolitis outcomes. They do not reduce clinical scores, hospitalization rates, or length of hospital stay. Any potential minor benefits must be weighed against the risks of steroid treatment. Corticosteroids are not recommended for routine use in bronchiolitis.

Antibiotics

Antibiotic prescriptions are common in children with acute bronchiolitis. However, bacterial infection in otherwise healthy children with bronchiolitis is exceedingly rare. Research on antibiotics in bronchiolitis has not identified any benefit. Further research is needed to identify the small subset of patients at high risk for secondary bacterial infection. Currently, antibiotics should be avoided unless there is clear evidence of a secondary bacterial infection.

Antivirals

Antiviral therapies like ribavirin are expensive, cumbersome to administer, offer limited benefit, and pose potential toxicity risks to caregivers. Therefore, they are not recommended for routine bronchiolitis treatment in otherwise healthy children. In patients with or at risk for particularly severe disease, antivirals might be considered on a case-by-case basis in consultation with specialists.

Chest Physiotherapy

Reviews of clinical trials comparing chest physiotherapy to no treatment have shown that neither vibration and percussion nor passive expiratory techniques improve clinical scores, reduce hospital stay, or shorten symptom duration. Chest physiotherapy is not recommended for bronchiolitis treatment.

Cool Mist Therapies or Aerosol Therapy with Isotonic Saline

Cool mist and isotonic saline aerosol therapies have been used for bronchiolitis management with limited supporting evidence. A Cochrane review concluded that there is no evidence to support or refute their use in bronchiolitis management.

Other therapies for critically ill infants with severe bronchiolitis, such as helium/oxygen mixtures, nasal continuous positive airway pressure, mechanical ventilation, and surfactant, are beyond the scope of this guideline.

MONITORING IN HOSPITAL FOR BRONCHIOLITIS

Patients hospitalized with bronchiolitis should be cared for in an environment equipped with suction equipment and supplemental oxygen delivery systems. Strict infection control measures are essential. Respiratory contact isolation may reduce nosocomial transmission, but the benefits of cohorting patients are debated.

Regular and repeated clinical assessments by experienced staff are the most critical aspect of monitoring hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis. Monitoring should include documented assessments of respiratory rate, work of breathing, oxygen saturation, auscultation findings, and general condition, including feeding and hydration status. Scoring tools for standardization and communication exist but lack sufficient evidence of impact on patient outcomes to recommend any specific tool.

Electronic monitoring of vital signs and oxygen saturation should not replace regular clinical assessments by experienced personnel. Furthermore, continuous monitoring may prolong hospital stay, especially if staff react to normal transient dips in oxygen saturation or changes in heart and respiratory rates by re-initiating oxygen therapy. Pulse oximetry accuracy is relatively poor, particularly at saturations <80%.

The primary purpose of cardiac and respiratory monitoring is to detect apnea episodes requiring intervention. Apnea incidence in RSV bronchiolitis may be lower than previously thought. Continuous electronic cardiac and respiratory monitoring may be useful for high-risk patients in the acute phase but are not necessary for most bronchiolitis patients.

Oxygen saturation monitoring aids in decisions about escalating or weaning oxygen therapy. Continuous versus intermittent monitoring of oxygen saturation remains controversial. Continuous monitoring might be more sensitive for detecting deterioration, but many healthy infants exhibit transient oxygen saturation dips, and length of stay may be prolonged if oxygen therapy is guided by arbitrary saturation targets. Current clinical trials are exploring best practices in this area. A reasonable approach is to adjust oxygen saturation monitoring intensity based on the patient’s clinical status. Continuous monitoring is appropriate for high-risk patients early in the disease, while intermittent monitoring is suitable for lower-risk patients and all patients improving clinically, feeding well, weaning from oxygen, and showing reduced work of breathing.

Discharge readiness should be based on clinical judgment and consideration of the family’s ability to recognize and respond to deterioration signs. Generally, patients can be safely discharged when they are improving clinically and meet the criteria in Table 7.

TABLE 7. Discharge Criteria from Hospital for Bronchiolitis

| Discharge Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| Tachypnea and work of breathing improved | Breathing rate and effort have decreased |

| Maintain O2 saturations >90% without supplemental oxygen OR stable for home oxygen therapy | Adequate oxygenation on room air or stable on home oxygen |

| Adequate oral feeding | Infant is able to feed sufficiently by mouth |

| Education provided and appropriate follow-up arranged | Family is informed and has a follow-up plan |

CONCLUSIONS ON BRONCHIOLITIS DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

The optimal management of bronchiolitis in otherwise healthy children has been a long-standing debate. A 1965 review advised patience and avoiding unnecessary and futile therapies. This wise advice has often been overlooked. Optimal bronchiolitis management in healthy children remains primarily excellent supportive care. While research into other treatments continues, healthcare providers should remember ‘primum non nocere’ (first, do no harm) as the guiding principle in treating otherwise healthy children with bronchiolitis.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR BRONCHIOLITIS MANAGEMENT

- Bronchiolitis diagnosis is clinical, based on history and physical examination. Diagnostic studies, including chest radiographs, blood tests, and viral/bacterial cultures, are not recommended in typical cases.

- Hospital admission decisions should be based on clinical judgment, considering the risk of severe disease progression, respiratory status, hydration ability, and family coping capacity.

- Management is primarily supportive, including hydration, minimal handling, gentle nasal suctioning, and oxygen therapy.

- Isotonic solutions (0.9% NaCl/5% dextrose) are recommended for IV hydration, with routine serum sodium monitoring.

- Epinephrine use is not recommended in routine cases. If tried in the emergency department, continued use requires clear clinical improvement.

- Current evidence does not firmly support 3% hypertonic saline. Outpatient use is not supported, but potential benefit exists for hospitalized children >3 days.

- Salbutamol (Ventolin) use is not recommended in routine cases.

- Corticosteroid use is not recommended in routine cases.

- Antibiotic use is not recommended unless bacterial infection is suspected.

- Chest physiotherapy is not recommended.

- Thoughtful oxygen saturation monitoring is recommended for hospitalized patients. Continuous monitoring may be indicated for high-risk children in the acute phase, with intermittent monitoring appropriate for lower-risk and improving patients.

Acknowledgments

This position statement was reviewed by the Community Paediatrics Committee and the Hospital Paediatrics and Emergency Medicine Sections of the Canadian Paediatric Society, and representatives of the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

Footnotes

CPS ACUTE CARE COMMITTEE

Members: Laurel Chauvin-Kimoff MD (Chair), Isabelle Chevalier MD (Board Representative), Catherine A Farrell MD, Jeremy N Friedman MD, Angelo Mikrogianakis MD (past Chair), Oliva Ortiz-Alvarez MD

Liaisons: Dominic Allain MD, CPS Paediatric Emergency Medicine Section; Tracy MacDonald BScN, Canadian Association of Paediatric Health Centres; Jennifer M Walton MD, CPS Hospital Paediatrics Section

CPS DRUG THERAPY AND HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES COMMITTEE

Members: Mark L Bernstein MD, François Boucher MD (Board Representative), Ran D Goldman MD, Geer’t Jong MD, Philippe Ovetchkine MD, Michael J Rieder MD (Chair),

Liaisons: Daniel Louis Keene MD, Health Canada; Doreen Matsui MD (past Chair)

Principal authors: Jeremy N Friedman MD, Michael J Rieder MD, Jennifer M Walton MD

The recommendations in this statement are guidelines, and variations based on individual circumstances may be appropriate. All Canadian Paediatric Society position statements and practice points are regularly reviewed. Consult the Position Statements section of the CPS website (www.cps.ca) for the most current version.

REFERENCES

1 American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2006;118(4):1774-93.

2 Hall CB, Hall WJ, Gala CL, et al. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children with and without underlying cardiac disease. J Pediatr 1979;95(5 Pt 1):763-8.

3 Welliver RC. Respiratory syncytial virus and other respiratory viruses. In: Feigin RD, Cherry JD, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, eds. Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases, 5th edn. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 2004:2081-101.

4 Wright M, Piedimonte G. Bronchiolitis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2011;32(5):573-81.

5 Smyth RL, Openshaw PJ. Bronchiolitis. Lancet 2010;375(9711):316-22.

6 Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. Prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections: Position statement update. Paediatr Child Health 2003;8(1):46-50.

7 Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al; American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2014;134(5):e1474-502.

8 приводит данные об увеличении числа госпитализаций детей с бронхиолитом за последние 30 лет.

9 Molteni KH, Warshawski S, Dollaghan C, Patel H, Parkin PC. Resource utilization and costs associated with bronchiolitis hospitalizations in Ontario children. J Pediatr 2007;150(4):382-7.

10 примеры исследований, демонстрирующих значительную заболеваемость и влияние на семьи.

11 McMillan JA, Serwint JR, Howard CR, et al. Variation in resource utilization in infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19(6):516-20.

12 зато стандартизация подхода к лечению бронхиолита показала снижение использования диагностического тестирования и ресурсов.

13 примеры исследований, подтверждающих снижение затрат и улучшение результатов при стандартизации лечения.

14 Freed GL, Bordley WC, Clark SJ, Konrad TR, Carey TS. Variation in resource utilization for children hospitalized with bronchiolitis: a population-based study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1996;150(1):37-42.

15 например, исследование, показывающее, что рентгенография грудной клетки может привести к увеличению использования антибиотиков.

16 риски и неинформативность рентгенографии грудной клетки при типичном бронхиолите.

17 сомнения в необходимости рутинного взятия мазков из носоглотки из-за высокой частоты коинфекций.

18 неинформативность общего анализа крови для прогнозирования серьезных бактериальных инфекций.

19 низкая, но не нулевая вероятность сопутствующей бактериальной инфекции у детей с бронхиолитом.

20 риск инфекций мочевыводящих путей у маленьких детей с бронхиолитом.

21 бактериемия как редкое осложнение бронхиолита.

22 уточнение возраста детей с наибольшим риском бактериальных инфекций.

23 течение бронхиолита и ухудшение состояния в первые 72 часа.

24 ограничения клинических шкал и отдельных параметров для прогнозирования исходов.

25 возраст и насыщение кислородом как факторы риска госпитализации.

26 значение возраста и ЧДД как предикторов госпитализации.

27 влияние пороговых значений насыщения кислородом на решения о госпитализации.

28 описание высокопоточной назальной канюли как альтернативы.

29 потенциал высокопоточной назальной канюли для снижения потребности в ИВЛ.

30 дополнительные данные о преимуществах высокопоточной назальной канюли.

31 недостаточность доказательств эффективности высокопоточной назальной канюли.

32 частота необходимости в восполнении жидкости у госпитализированных пациентов.

33 сравнение эффективности назогастрального и внутривенного путей введения жидкости.

34 предпочтительные изотонические растворы для внутривенного введения.

35 риск гипонатриемии при внутривенном введении жидкости.

36 эпинефрин и снижение частоты госпитализаций, систематический обзор.

37 комбинация эпинефрина и стероидов и снижение частоты госпитализаций.

38 глубокая назальная аспирация и увеличение продолжительности пребывания в стационаре.

39 гипертонический солевой раствор и улучшение клинических показателей.

40 смешанные результаты исследований гипертонического солевого раствора после Кокрановского обзора.

41 дополнительные исследования гипертонического солевого раствора.

42 бронходилататоры не улучшают насыщение кислородом и не сокращают продолжительность пребывания в стационаре.

43 недостаточность β-адренорецепторов у младенцев.

44 кортикостероиды не улучшают клинические показатели.

45 кортикостероиды не снижают частоту госпитализаций.

46 антибиотики не показаны при бронхиолите, редкость бактериальных инфекций.

47 противовирусная терапия рибавирином не рекомендуется рутинно.

48 противовирусные препараты могут рассматриваться в тяжелых случаях по согласованию со специалистами.

49 физиотерапия грудной клетки неэффективна при бронхиолите, Кокрановский обзор.

50 отсутствие доказательств эффективности прохладного тумана и аэрозолей.

51 гелий/кислород при тяжелом бронхиолите.

52 CPAP при тяжелом бронхиолите.

53 сурфактант при тяжелом бронхиолите.

54 изоляция и снижение нозокомиальной передачи.

55 противоречивые данные о пользе когортирования пациентов.

56 шкалы оценки и стандартизация.

57 ограниченное влияние шкал оценки на результаты лечения.

58 отсутствие доказательств в пользу рутинного использования шкал оценки.

59 непрерывный мониторинг может продлить пребывание в стационаре.

60 ограниченная точность пульсоксиметрии.

61 низкая частота апноэ при РСВ-бронхиолите.

62 транзиторные снижения насыщения кислородом у здоровых детей.

63 физиологические снижения насыщения кислородом.

64 совет избегать ненужной терапии, обзор 1965 года.

65 частое игнорирование совета из обзора 1965 года.