Abstract

Buccal space masses, while relatively uncommon, present a unique diagnostic challenge due to the anatomical complexity and diverse tissue composition of the head and neck region. This area, often overlooked, can harbor a variety of lesions manifesting as unilateral buccal swellings. This article, tailored for automotive repair experts with an interest in diagnostic processes akin to vehicle troubleshooting, presents a series of cases illustrating the differential diagnosis of buccal space masses. We highlight various etiologies, ranging from benign tumors to other less common conditions, emphasizing the importance of a systematic approach to diagnosis. Understanding the Buccal Mass Differential Diagnosis is crucial for effective clinical management and parallels the systematic diagnostic approaches used in automotive repair.

Keywords: buccal mass differential diagnosis, unilateral facial swelling, neoplasm, surgical treatment, benign tumor, automotive diagnostics

Introduction

In the intricate landscape of the head and neck anatomy, the buccal space stands as a small yet significant area defined by fascial layers. Often considered an “overlooked space” due to its diminutive size and the presence of the buccal fat pad, this region is nonetheless critical in understanding facial pathologies. The buccal fat pad, typically more prominent in children, resides between the buccinator and masseter muscles, contributing to the fullness of the cheeks [1]. Anatomically, the buccal space is bordered anteriorly by facial expression muscles, posteriorly by the masseter muscle and mandible, laterally by the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia, superiorly by the zygomatic process and muscles, and inferiorly by the depressor anguli oris muscle and mandibular fascia [2, 3]. Like diagnosing complex automotive issues, identifying the root cause of a buccal mass requires a detailed understanding of the system – in this case, the intricate anatomy of the buccal space.

This space is not isolated; it communicates with the submandibular and masticatory spaces, further complicating diagnostic considerations. Within its confines, the buccal space houses vital structures including the parotid duct, accessory parotid tissue, facial artery and vein, lymphatic channels, minor salivary glands, and branches of both the mandibular and facial nerves [1]. This rich neurovascular and glandular content explains the diverse range of lesions that can arise in this region, presenting as buccal masses [4]. Just as a mechanic must consider various components when diagnosing a car problem, clinicians must consider a wide differential diagnosis for buccal space masses.

Statistical evidence indicates that salivary gland tumors, particularly pleomorphic adenoma, are the most frequent pathologies encountered in the buccal space[1]. Patients typically present with a noticeable cheek mass or swelling, palpable upon clinical examination. This article, echoing the systematic approach used in automotive diagnostics, presents four distinct cases of unilateral buccal space masses originating from varied pathologies within and adjacent to the buccal space. Our aim is to highlight the process of buccal mass differential diagnosis, essential for accurate clinical assessment and treatment planning. This retrospective case series, conducted at a tertiary care academic center between 2014 and 2019, adheres to the PROCESS guidelines for case series reporting [5].

Case series

Case 1

A 50-year-old woman, otherwise healthy, presented to the Department of Oral Medicine with a six-year history of a painful nodular swelling in her right cheek. Initially painless, the swelling had gradually increased in size and became painful in the week prior to presentation. She reported no history of trauma or pus discharge. Extraoral examination revealed mild diffuse swelling in the right cheek area, with a palpable, well-circumscribed nodule of approximately 2×2 cm. The overlying skin was normal. The nodule was mobile, firm yet slippery, and tender to palpation. The lesion was extraoral, and intraoral examination was unremarkable. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) revealed a mildly enhancing lesion in the right buccal space with peripheral calcified specks (Figure 1). Surgical excision was performed, and a well-encapsulated mass was removed from the buccal space (Figure 2). Histopathological examination showed a highly vascular connective tissue stroma with irregular vascular spaces lined by endothelial cells, filled with red blood cells and supported by collagen fibers, consistent with capillary hemangioma with phlebolith.

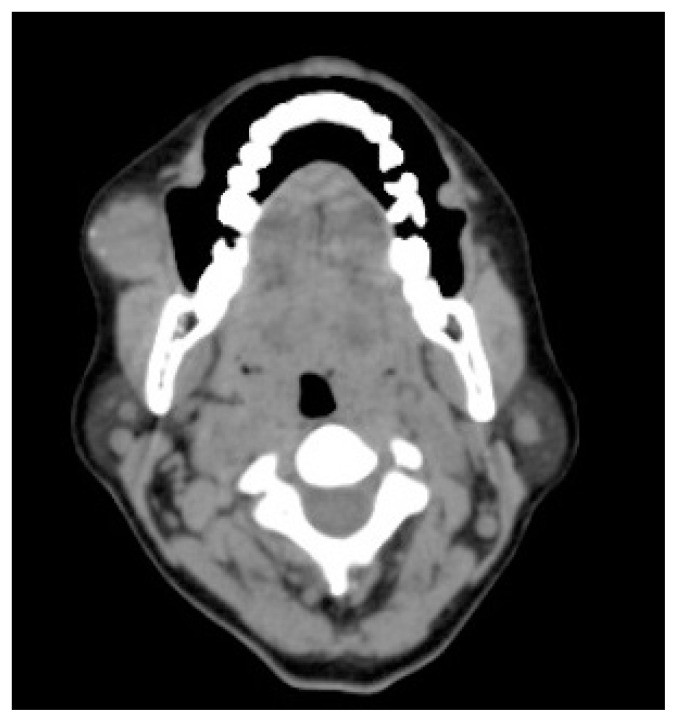

Figure 1.

Contrast enhanced computed tomographic axial section showing a slightly enhancing lesion with calcified spots at the edge within the right buccal space, indicative of diagnostic imaging for buccal mass differential diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Intra-operative view demonstrating the complete removal of a well-defined encapsulated mass from the right buccal space, a key step in treating buccal masses.

Case 2

A 37-year-old healthy male presented with an eight-year history of a right cheek swelling. The swelling was non-progressive and asymptomatic. Examination revealed a well-circumscribed, mobile, soft to firm swelling. The intraoral mucosa was normal, and the swelling was within the buccal mucosa. Ultrasonography showed mixed echogenicity with thin internal septae, measuring 3.0 × 0.8 cm. Excisional biopsy was performed, and histopathological features confirmed a lipoma.

Case 3

A 36-year-old female reported a painless, non-progressive left cheek swelling of two months duration. There was no history of trauma, and her medical history was unremarkable. Examination revealed a mobile, well-circumscribed swelling on the left buccal mucosa. Ultrasonography showed a hypoechoic lesion (10 × 7 mm) with peripheral and minimal central vascularity. CECT imaging showed a heterogeneously enhancing lesion, suggestive of a benign salivary gland tumor (Figure 3). Surgical enucleation was performed, and histopathology confirmed pleomorphic adenoma.

Figure 3.

Contrast enhanced computed tomographic coronal section showing a lesion with varied enhancement in the left buccal space, close to the masseter muscle, characteristic of salivary gland tumors in buccal mass differential diagnosis.

Case 4

A 41-year-old healthy woman presented with a two-month history of a painless right cheek swelling. The mass was submucosal and mobile. Histopathology of the excised lesion showed spindle-shaped cells with elongated nuclei in fascicles and vascular channels. Immunohistochemistry showed strong cytoplasmic expression of smooth muscle actin (SMA) and absence of p63 nuclear expression, leading to a final diagnosis of solitary myofibroma of the left buccal space.

These cases illustrate the diverse benign lesions that can manifest as unilateral buccal space masses, all presenting with a similar clinical feature. All patients were followed up for one year, with no reported recurrences.

Discussion

Similar to diagnosing an unusual noise in a vehicle which could stem from various components, unilateral buccal space swellings require a comprehensive buccal mass differential diagnosis to pinpoint the exact cause. A range of soft tissue lesions can present as submucosal masses in this region. When considering differential diagnoses, several factors are crucial: patient age, onset and progression of swelling, and clinical examination findings. Palpation, visual inspection, and understanding the lesion’s consistency in relation to surrounding tissues provide vital diagnostic clues. Common causes of unilateral buccal space swellings are categorized by tissue origin in Table I.

Table I.

Common lesions presenting as unilateral buccal space swellings classified according to tissue of origin, aiding in buccal mass differential diagnosis.

| Tissue of origin | Condition | Differentiating clinical clues |

|---|---|---|

| Odontogenic source | Spread of odontogenic infection to the buccal space, cellulitis | Associated with a decayed tooth, acute onset of pain, responds to antibiotics and anti-inflammatory medication, similar to identifying infection as cause of system failure. |

| Blood vessel | Hemangioma, AV malformation | Red, bluish, or brownish color, surface may be irregular or smooth, possible pulsatility or bruits upon auscultation, much like checking for fluid leaks or pressure anomalies in automotive systems. |

| Nerve tissue | Neuroma, Neurofibroma | History of trauma to the area, firm nodule, occasionally tender on palpation, analogous to tracing wiring issues after physical damage. |

| Adipose tissue | Lipoma, liposarcoma | Soft, mobile, asymptomatic mass, similar to identifying a non-critical, benign component in a larger system. |

| Salivary glands | Sialolithiasis of Stenson’s duct, Sialadenitis, Tumors: Pleomorphic adenoma, acinic cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma | Painful swelling, acute onset (sialolithiasis, sialadenitis), painless or painful chronic swelling (tumors), resembling issues in fluid systems like cooling or lubrication in vehicles. |

| Lymphoid tissue | Reactive lymphadenopathy of buccal/facial/intraparotid nodes, Metastatic lymphadenopathy, Lymphomas, Lymphangioma, Calcified lymph node | Painless asymptomatic swelling, could indicate systemic issues or localized reactions, similar to warning lights indicating broader or specific problems. |

| Muscle tissue | Rhabdomyoma, Rhabdomyosarcoma | Asymptomatic smooth, well-circumscribed, mobile mass, akin to issues within mechanical components, requiring closer inspection. |

| Other | Foreign body granuloma, Kimura disease, Solitary fibrous tumor, Traumatic herniation of buccal fat pad | History of trauma or surgery (foreign body, herniation), enlarged lymph node (Kimura), painless slow-growing mass (solitary fibrous tumor), often requiring detailed history for diagnosis, like needing service records for vehicle diagnostics. |

Lipoma and hemangioma are frequently encountered benign lesions in the oral cavity [6]. Buccal space lesions of vascular and salivary gland origin are commonly reported. Metastatic buccal lymph nodes from squamous cell carcinoma should also be considered in the buccal mass differential diagnosis [3].

Unilateral buccal swellings can arise from infections, inflammation, benign, or malignant neoplastic conditions. Odontogenic infections spreading to the buccal space are a common cause of acute unilateral swelling. Muscle-origin tumors are also relevant due to the proximity of masticatory muscles. Lesions may originate de novo within the buccal space or extend from adjacent sites [1]. Rarely, collision lesions, where two distinct pathologies coexist, can occur in the buccal space [7].

Capillary hemangioma, as seen in Case 1, is an uncommon benign soft tissue tumor in the oral cavity, accounting for a small percentage of intraoral neoplasms, predominantly in females in their second to third decades. The buccal mucosa is a common site. These typically present as painless, sessile or pedunculated masses of varying sizes. Phleboliths, calcified thrombi due to blood stagnation, are often associated with cavernous hemangiomas [8].

Lipomas, benign adipose tissue tumors, are also uncommon in the oral cavity, as seen in Case 2. They appear as small, well-defined masses on the buccal mucosa or tongue, usually asymptomatic, with a smooth surface and sessile or pedunculated base. Treatment involves simple surgical excision, with low recurrence rates [9].

Salivary gland neoplasms, exemplified by pleomorphic adenoma in Case 3, usually present as slow-growing, painless masses. Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common benign salivary gland tumor, with the palate being a frequent intraoral site. Minor salivary gland neoplasms constitute a significant portion of these tumors [10].

Myofibromas, like the one in Case 4, are rare benign myofibroblastic tumors, typically affecting individuals under 20, with the mandible being a common site. Trauma is a potential causative factor. They present as firm, mostly asymptomatic, pink-red masses. Solitary myofibromas are treated with total excision and have a favorable prognosis [11, 12].

In conclusion, the buccal space, despite its size, is a complex anatomical area prone to various pathologies. Unilateral buccal space swellings pose diagnostic challenges due to the diverse tissues and potential lesions. Clinicians, much like automotive experts diagnosing complex issues, must be well-versed in the buccal mass differential diagnosis to accurately identify and manage these conditions effectively, ensuring optimal patient care.