Introduction

Gingival lesions, commonly manifesting as a bump on the gums, are frequently encountered in dental practice. These lesions represent a significant portion of oral pathology diagnoses. While the vast majority are reactive hyperplasias, often triggered by chronic irritants, a spectrum of other conditions, including developmental anomalies and neoplasms, can also present on the gingiva. This diversity in etiology underscores the importance of accurate differential diagnosis when faced with a bump on the gums. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the clinical and histological differential diagnoses for gingival lumps, guiding clinicians through the diagnostic process and highlighting potential pitfalls. Understanding the Bump On The Gums Differential Diagnosis is crucial for effective patient management and treatment planning.

A Word on Terminology

In the field of histopathology, and particularly concerning lesions of the gingiva, terminology can be inconsistently applied. Some terms, while not strictly accurate, have become entrenched in common usage. Examples include the terms ‘polyp’ and ‘epulis’ when used as histological diagnoses, the broad application of ‘fibroma’ in this context, and the regionally variable use of ‘peripheral ossifying fibroma’. While rigid standardization of terminology might be impractical, it is paramount that histopathologists and referring clinicians share a clear and mutual understanding of the terms employed. This shared understanding is vital for effective communication of diagnoses and the subsequent development of appropriate treatment strategies. Throughout this discussion, we will indicate common synonyms where relevant to enhance clarity and avoid confusion related to bump on the gums differential diagnosis.

Reactive Lesions

Fibrous Hyperplasia of the Gingiva

Epidemiology

Inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia, also known as fibroepithelial polyp or fibroma (and fibrous epulis when specifically on the gingiva), is an exceedingly common reactive gingival lesion. It is estimated that fibrous hyperplasia accounts for a substantial proportion, up to 40%, of mucosal pathologies observed in large patient series. These lesions can occur across a wide age range, with a slightly higher prevalence in females.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

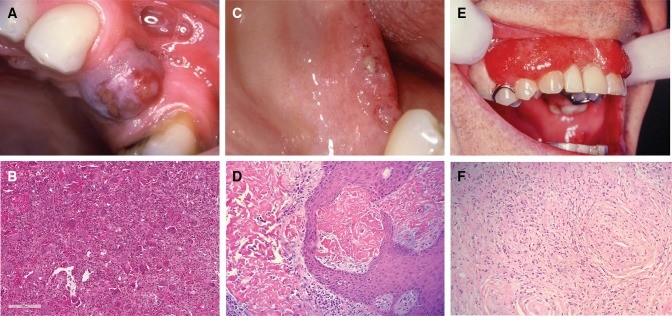

In patients with teeth, fibrous hyperplasia typically manifests on the interdental papilla, but it can also involve the facial aspect of the tooth (Fig. 1a). Larger lesions may extend across the contact point between teeth, creating a “dumb-bell” appearance, although this presentation is more classically associated with peripheral giant cell granuloma. The color of these lesions usually matches the surrounding mucosa, although focal ulceration can occur.

More widespread and pronounced lesions are often observed in patients taking certain medications, such as phenytoin, nifedipine, and other calcium channel blockers, or cyclosporine. Drug-induced gingival hyperplasia represents an exaggerated form of the focal reactive lesions described above (Fig. 1b). In individuals who are edentulous or partially dentate, similar lesions can develop on the alveolar ridge in response to poorly fitting dentures, often termed denture irritation hyperplasia or denture hyperplasia. These denture-related lesions are most frequently found on the mucosa in contact with the denture periphery and typically present as broad-based, leaf-like folds of tissue.

Fig. 1. a A large fibrous epulis on maxillary gingiva. b Widespread fibrous gingival enlargement on a patient on cyclosporine therapy. c Histological image of a nodule of fibrous hyperplasia of the gingiva (H&E, Overall magnification × 20). d Histological image showing large stellate fibroblasts in a giant cell fibroma (H&E, overall magnification × 200). e An ulcerated vascular lesion on the maxillary gingiva of a pregnant patient in mid-trimester. f The histology of a vascular epulis/pyogenic granuloma shows attenuated or ulcerated epithelium with an underlying endothelial proliferation. This may have a lobular pattern (H&E, overall magnification × 200)

The clinical bump on the gums differential diagnosis for fibrous hyperplasia primarily includes other reactive gingival lesions, such as pyogenic granuloma and peripheral giant cell granuloma. In cases of more generalized gingival enlargement, hereditary gingival fibromatosis should be considered. This condition can occur in isolation or as part of a syndrome. Genetic studies have linked mutations in the Son-of-Sevenless-1 (SOS1) gene to isolated hereditary gingival fibromatosis.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

Histologically, fibrous hyperplasia is characterized by hyperplastic, typically keratinized epithelium overlying a nodular mass of fibrous connective tissue (Fig. 1c). The degree of collagenization and vascularity within the lesion varies depending on its maturity and the presence or absence of inflammation. The fibroblast component is generally bland, composed of fine, spindle-shaped cells, and most lesions are relatively sparsely cellular. However, some lesions exhibit larger, stellate-shaped fibroblasts, and occasionally, multinucleated but cytologically benign cells (Fig. 1d). These variants are termed “giant cell fibroma” and are most commonly found on the gingiva of young adults.

Notably, up to one-third of fibrous hyperplastic lesions on the gingiva, particularly those on the maxillary labial gingiva and lesions that are or have been ulcerated, contain trabeculae of metaplastic bone. These lesions are termed peripheral ossifying fibroma (synonym: mineralizing fibrous epulis). The use of this terminology and the view of whether it represents a distinct entity varies geographically. However, research suggests that peripheral ossifying fibroma likely represents a variation in the reactive response to chronic irritation. Histologically, the mineralizing component consists of trabeculae or drop-like calcifications resembling woven bone or cementum within an active cellular stroma. Peripheral ossifying fibromas have a higher recurrence rate compared to other forms of fibrous epulis.

Vascular Epulis (Pyogenic Granuloma)

Epidemiology

The vascular epulis, also known as pyogenic granuloma, is a reactive vascular lesion that frequently occurs on the gingiva. These lesions develop in response to trauma or chronic irritation and are more common in females. Hormonal fluctuations are considered a contributing factor, as pyogenic granulomas are more prevalent during puberty, pregnancy (pregnancy epulis or granuloma gravidarum), and with the use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

Vascular epulis presents clinically as a soft, bright red swelling on the gingiva. Areas of ulceration may impart a greyish-yellow tinge to the lesion (Fig. 1e). Minor trauma readily provokes bleeding. The clinical bump on the gums differential diagnosis includes peripheral giant cell granuloma, as both lesions share a vascular nature. Generalized vascular lesions of the gingiva are less likely to be pyogenic granuloma; in such cases, systemic conditions causing gingival vascular proliferation, such as leukemia and granulomatosis with polyangiitis, should be considered.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

Histologically, vascular epulis is characterized by a proliferation of endothelial cells, arranged in sheets or small capillaries, often displaying a lobular architecture (Fig. 1f). Some lesions contain larger, dilated, thin-walled vascular spaces. The surrounding connective tissue is often loose and edematous, with potential red blood cell extravasation. The surface epithelium is frequently ulcerated. In most cases, the diagnosis is straightforward, particularly when a lobular pattern is evident. However, some lesions may exhibit solid islands of endothelial cells with a notable mitotic rate. Careful histological assessment is crucial to differentiate benign pyogenic granuloma from more concerning lesions on the gingiva and to avoid over-interpreting reactive features as malignancy.

Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma

Epidemiology

Peripheral giant cell granuloma (PGCG), also known as giant cell epulis, represents approximately 10% of epulides. PGCG occurs across a broad age range, with a slightly earlier peak incidence in males compared to females, and a general female predilection. While PGCG can arise in any gingival location in dentate patients or on the alveolar ridge in edentulous patients, they are most common anterior to the molar region and slightly more frequent in the mandible.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

PGCGs typically present as deep red to purple, sessile swellings that can reach a considerable size (Fig. 2a). They may extend through the contact point between teeth in a “dumb-bell” pattern. The clinical bump on the gums differential diagnosis includes ulcerated fibrous epulis and vascular epulis. As with fibrous hyperplasia, generalized gingival swelling necessitates consideration of systemic factors.

Fig. 2. a A PGCG in an edentulous span of the maxilla. b Numerous multinucleated giant cells in a vascular and monocellular background in PGCG (H&E, Overall magnification × 40). c Lesions of ligneous alveolitis on the edentulous mandibular ridge. d Fibrinous deposits are seen in ligneous gingivitis, closely associated with the surface epithelium. Whilst suggestive of amyloid, these are Congo Red negative (H&E, overall magnification × 100). e Widespread “strawberry gingivitis” appearance of the maxillary gingiva in a patient with GPA. f The classic histological features of GPA can be difficult find in a gingival biopsy. The photomicrograph shows a small vessel with leukocytoclastic vasculitis and a poorly formed granuloma to the left of it (H&E, overall magnification × 100)

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

Histologically, PGCG is characterized by a vascular and cellular stroma composed of mononuclear cells (fibroblasts, macrophages, and endothelial cells), interspersed with numerous multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 2b). The giant cells vary in size and number of nuclei. Fibrous septa may be present, and a band of fibrous tissue can separate the lesional tissue from the overlying epithelium. Extravasated red blood cells and hemosiderin pigment are commonly observed.

PGCGs are histologically indistinguishable from central giant cell granuloma and giant cell lesions of the jaws associated with hyperparathyroidism. Incomplete initial excision is common, and the pathologist’s report should note this, along with a recommendation for further investigations, such as radiological examination and serum calcium level measurement, to rule out these related conditions. Cherubism, while also involving giant cells, is rarely a histological differential diagnosis due to its distinctive clinical and radiological features, including family history, early onset swellings, and multiple radiolucent jaw lesions.

Ligneous Gingivitis

Epidemiology

Ligneous gingivitis is a rare condition resulting from an inherited plasminogen deficiency. It is observed in up to one-third of individuals with this deficiency.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of ligneous gingivitis is variable, ranging from focal lesions to generalized nodular gingival enlargement. Patients may report bleeding and soreness. The lesions exhibit an irregular surface and may ulcerate (Fig. 2c). An association with aggressive periodontal disease has been reported.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

Histologically, ligneous gingivitis is characterized by the accumulation of fibrin in the superficial lamina propria, often associated with blood vessels in this area. Extensive fibrin deposition can form large sheets, raising suspicion for amyloid. The surface epithelium may be attenuated or mildly hyperplastic, and a scattered inflammatory infiltrate is often present. The primary histological bump on the gums differential diagnosis is amyloidosis. Histochemical stains, such as Congo red or Sirius red, to exclude amyloid, and occasionally, trichrome stains (e.g., Martius scarlet blue) to highlight fibrinous material, can be valuable in confirming the diagnosis.

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA)

Epidemiology

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis, is a rare systemic condition with diverse clinical manifestations. While most presentations involve the respiratory tract, any organ system can be affected. GPA occurs across a wide age range, with a slight female predominance, and predominantly affects Caucasian individuals.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

Oral lesions occur in approximately 2% of GPA patients. The classic oral presentation is “strawberry gingivitis” (Fig. 2e). These lesions are nodular and erythematous with an irregular surface and a tendency to bleed easily. Lesions can be focal or widespread and may be asymptomatic. Ulceration and destructive lesions have also been reported. While the clinical appearance of strawberry gingivitis is characteristic, the bump on the gums differential diagnosis, particularly for focal lesions, may include some of the vascular lesions described earlier.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

The hallmark histological feature of GPA is destructive vasculitis, specifically leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Fig. 2f). Affected vessels show inflammatory cells throughout their walls, potentially leading to vessel obliteration and necrosis. Gingival lesions may also exhibit prominent red blood cell extravasation. Non-caseating epithelioid granulomas, sometimes containing multinucleated giant cells, may also be present. Diagnosis can be challenging in small gingival biopsies due to the potential absence of granulomas and limited vasculitis. Other granulomatous conditions, such as tuberculosis, certain fungal infections, Crohn’s disease, and sarcoidosis, must be excluded. Histochemical stains (Ziehl-Neelsen, Grocott, etc.) can aid in refining the differential diagnosis, depending on the histological features. Serological testing for PR3-ANCA should be considered if GPA is suspected.

Verruciform Xanthoma

Verruciform xanthoma most commonly occurs on the gingiva and palate. Given its frequent yellow coloration, readers are directed to specialized resources on “Yellow lesions of the oral mucosa” and “Non-HPV Papillary lesions of the oral mucosa” for detailed information. This highlights another aspect to consider in the bump on the gums differential diagnosis, which is lesion color.

Developmental Lesions

Congenital Epulis

Epidemiology

Congenital epulis, also known as granular cell epulis, is a rare soft tissue lesion that primarily develops on the anterior alveolar ridge of newborns. It is more common in females and in the maxilla.

Clinical Presentation

Congenital epulis is typically present at birth as a soft, mucosa-covered nodule. The size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. Spontaneous resolution of these lesions has been reported.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

The characteristic histological feature is a submucosal mass of large eosinophilic cells with granular cytoplasm. Importantly, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epithelium is absent, which helps differentiate it from granular cell tumor, the main bump on the gums differential diagnosis histologically. Furthermore, congenital epulis cells do not express S100 protein, unlike granular cell tumor cells.

Tori and Exostoses

Epidemiology

Torus palatinus (TP) and torus mandibularis (TM) are common bony protuberances found in the oral cavity, with a prevalence of 12–15%. They typically become apparent in early adulthood. TP is twice as common in females, while TM shows a slight male predominance. Buccal and palatal exostoses, which are multiple bony nodules, occur less frequently than tori. They are associated with increasing age and are more common in men.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

TP presents in the midline of the hard palate, and TM presents on the lingual aspect of the mandible above the mylohyoid line. Exostoses are usually observed as multiple nodules on the buccal aspect of the maxilla (Fig. 3a). Their development is considered multifactorial, but TP and TM have been linked to tooth attrition, supporting the theory that mechanical stress from bruxism may contribute to their formation. Tori and exostoses generally do not pose a clinical diagnostic challenge.

Fig. 3. a Multiple bony swellings affecting the labial aspect of the maxillary gingivae, consistent with exostoses. b Bluish swelling affecting the attached gingivae in the lower left canine/premolar area, consistent with a gingival cyst (Photograph kindly provided by Dr Susan Muller). c Oral mucosa containing a cystic structure lined by thin epithelium with focal thickenings in a gingival cyst (H&E, overall magnification × 20). d An odontogenic fibroma is characterized by strands of odontogenic epithelium in a collagenous stroma (H&E, overall magnification × 10). e Peripheral ameloblastoma showing islands of odontogenic epithelium with characteristic peripheral palisading (H&E, overall magnification × 4). f Cords of atypical epithelial cells in fibrous stroma in a metastatic lobular carcinoma of breast (H&E, overall magnification × 20)

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

The histology of tori and exostoses is identical; differentiation is based on clinical presentation. Histology reveals mature lamellar bone with scattered osteocytes and minimal osteoblastic activity. Both cortical and trabecular bone are present.

Gingival Cyst

Epidemiology

Gingival cyst of the adult is a relatively uncommon lesion, accounting for a small percentage (0.2%) of odontogenic cysts. It typically presents in the sixth decade of life and is more prevalent in women.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

Gingival cysts usually present as a painless, bluish swelling on the gingiva (Fig. 3b). They are most frequently encountered in the incisor, canine, and premolar regions of the mandible. Correct clinical diagnosis is achieved in approximately 50% of cases. Clinically, a mucocele may be considered in the bump on the gums differential diagnosis due to the bluish, translucent appearance of a gingival cyst. Radiographic evaluation is necessary to confirm the soft tissue location and rule out intraosseous involvement.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

Histologically, gingival cysts are typically small and lined by a thin epithelium resembling reduced enamel epithelium, composed of 1–3 layers of flat to cuboidal cells (Fig. 3c). The fibrous connective tissue wall is typically uninflamed, and separation between the epithelium and connective tissue is often observed. Focal epithelial thickenings are frequently present.

Histologically, gingival cyst is indistinguishable from lateral periodontal cyst. Therefore, radiographic examination is essential to exclude an intraosseous lesion. Gingival cysts can cause resorption of underlying cortical bone, which may appear as a diffuse radiolucency, whereas lateral periodontal cysts usually present as well-defined radiolucencies between tooth roots. Gingival cysts are usually unicystic, but multicystic variants can occur. In such cases, botryoid odontogenic cyst, the multicystic variant of lateral periodontal cyst, must be considered in the bump on the gums differential diagnosis.

Neoplastic: Benign

Peripheral Odontogenic Tumors

Epidemiology

Peripheral odontogenic tumors are rare lesions, with peripheral odontogenic fibroma (POF) and peripheral ameloblastoma (PA) being the most common. In case series, peripheral odontogenic tumors represent a small fraction of oral biopsies and a small percentage of all odontogenic tumors. POF is the most common peripheral odontogenic tumor, even more common than its central counterpart. It typically presents around 32 years of age and has a slight female predilection. PA presents at a slightly older mean age of 52 years, higher than its intraosseous counterpart, and shows a slight male predilection.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

POF presents as a gingival swelling, usually with intact overlying mucosa. It is more common in the mandibular incisor, canine, and premolar area, while central odontogenic fibroma is more often seen in the mandibular molar and premolar regions, as well as the anterior maxilla. PA exhibits variable clinical presentations and may have a granular or erythematous surface. They are most common in the mandibular premolar region.

The clinical bump on the gums differential diagnosis for a localized gingival mass typically includes fibrous hyperplasia, pyogenic granuloma, or giant cell lesion. If a PA has a granular surface, squamous papilloma may also be considered. Intraosseous odontogenic tumors presenting peripherally must be excluded with appropriate radiology. However, peripheral lesions can cause superficial bone erosion.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

POF is microscopically similar to central odontogenic fibroma, characterized by a collagenous stroma containing bland-appearing strands of odontogenic epithelium and potentially hard tissue formation (Fig. 3d). PA can exhibit any of the histopathological features seen in intraosseous ameloblastoma. Typically, the follicular form is identified, consisting of islands of odontogenic epithelium in a fibrous stroma (Fig. 3e). The odontogenic epithelium resembles the enamel organ with peripheral palisaded ameloblast-like cells and a central stellate reticulum-like region.

Sclerosing odontogenic carcinoma is a potential histological differential diagnosis for POF; however, it is more infiltrative and typically exhibits perineural invasion. The bump on the gums differential diagnosis for PA includes salivary gland tumors with similar histology and basal cell carcinomas, although oral mucosal involvement of basal cell carcinoma is rare. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in uncertain cases.

Neoplastic: Malignant

Verrucous Carcinoma (VC)

Epidemiology

Within the oral cavity, the gingiva (12%) and buccal mucosa (10%) are the most common sites for verrucous carcinoma (VC), unlike conventional squamous cell carcinoma, which is more frequently found on the lateral tongue border and floor of the mouth.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

VC presents as a thickened, white lesion with a roughened or papillary surface. The degree of whiteness and hyperplasia can vary within the lesion. VC tends to grow slowly and rarely metastasizes. Clinically, VC is indistinguishable from verrucous hyperplasia. Often, a spectrum of disease exists within the same lesion. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma may have a similar appearance. Smaller, subtle lesions may be confused with verruciform xanthoma, traumatic keratosis, or papilloma in the bump on the gums differential diagnosis.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

VC is characterized by extensive hyperplasia of rete processes that extend deeply into the connective tissue, creating a “buttress” between the carcinoma and adjacent epithelium. Varying degrees of hyperkeratosis and keratin plugging contribute to the verrucous surface morphology. Cellular and nuclear pleomorphism are minimal.

The classic histological challenge is distinguishing VC from verrucous hyperplasia, particularly in small or superficial biopsies. VC diagnosis requires rete pegs extending beneath the level of adjacent epithelium. Without this buttress, differentiation can be very difficult. Conventional squamous cell carcinoma can also exhibit exo-endophytic growth but typically shows significantly more cellular atypia and pleomorphism with invasive tumor islands in the superficial connective tissue.

Metastases

Epidemiology

Metastatic disease to the oral cavity often represents secondary spread from other metastatic sites, most commonly the lungs. Metastases to the gingiva are among the most common sites for oral metastases. Individuals between the fifth and seventh decades are most commonly affected, with a male predominance (2:1 ratio). Gingival metastases most commonly originate from the lung, kidney, and skin in men, and from the breast, genital organs, and lung in women. Metastases from the gastrointestinal tract and prostate are also possible.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of metastatic lesions is usually non-specific, but swelling, ulceration, and/or adjacent tooth mobility are common (Fig. 3a). Other malignant tumors, such as squamous cell carcinoma, lymphoma, and melanoma, are often considered in the bump on the gums differential diagnosis. A history of malignancy elsewhere in the body should always raise suspicion for metastasis.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

It is impractical to discuss every tumor type that can metastasize to the gingiva; the key is to consider metastasis, especially when the morphology is unusual for tumors typically seen in the head and neck region. Immunohistochemistry is a valuable tool for confirming the primary site of origin. The histological appearance of metastases varies greatly depending on the primary tumor site. For example, renal cell carcinoma metastasis consists of sheets of bland clear cells in a vascular stroma (typically RCC, CD10, PAX8 positive). In the gingiva, clear cell carcinoma and clear cell odontogenic carcinoma would need to be excluded (CD10, PAX8, RCC negative). Lobular carcinoma of the breast tends to present as cords of cells similar to polymorphous adenocarcinoma, but the former is usually ER and PR positive, unlike the latter (Fig. 3f).

Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS)

Epidemiology

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is invariably associated with HHV8 infection. While there are four epidemiological categories of KS, the AIDS-related type is the primary one associated with oral manifestations. Oral KS is most common in the fourth and fifth decades of life, with the palate and gingiva being the most frequently affected sites.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

KS lesions range from subtle areas of discoloration (often red/purple macules and papules) to more extensive nodular lesions with a more concerning appearance (Fig. 4a). The bump on the gums differential diagnosis often includes vascular lesions like hemangioma, pyogenic granuloma, and giant cell epulis, especially for nodular lesions. Advanced lesions can become large and ulcerated, necessitating consideration of other malignancies, such as squamous cell carcinoma.

Fig. 4. a Red, nodular swelling affecting the facial gingiva above the left maxillary canine and lateral incisor in Kaposi Sarcoma. b Streams of spindled cells with slit-like vessels and lymphangiomatous pattern superficially in Kaposi’s sarcoma (H&E, overall magnification × 4). c Non-Hodgkin lymphoma presenting as an ulcerated swelling affecting the posterior left retromolar region. d Generalized erythema and swelling affecting the gingiva in a case of AML. e Connective tissue effaced by sheets of atypical myeloid cells in AML (H&E, overall magnification × 20). f Chondrosarcoma classically has a lobular architecture, with blue-grey cartilaginous matrix (H&E, overall magnification × 4)

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

Early KS lesions (patch stage) are subtle, composed of thin, slit-like vessels within the lamina propria that transect collagen fibers and are associated with extravasated red blood cells and lymphocytes. In the plaque stage, spindle-cell proliferation becomes more evident, associated with hyaline globules (Kamino bodies). The nodular stage exhibits sheets of atypical spindle cells with increased mitoses (Fig. 4b). Tumor cells are positive for endothelial markers like CD31 and CD34 but characteristically positive for HHV8.

Early KS features can be easily overlooked. The increased vascularity may be mistaken for granulation tissue related to recent ulceration or trauma. In more cellular phases, the histological bump on the gums differential diagnosis includes other spindle cell neoplasms with vasoformative qualities, such as angiosarcoma (HHV8 negative).

Lymphoma/Leukemia

Epidemiology

The head and neck is the second most common extranodal site for lymphoma (11–33%), typically affecting individuals over 50 years old. Intraorally, common sites include the vestibule, gingiva, mandible, palate, maxilla, and tongue. The majority are Non-Hodgkin B cell lymphomas (mostly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), but T-cell lymphomas account for a proportion of oral lymphomas in certain populations. Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) of monocytic derivation is the most common leukemia type to affect the gingivae.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

Lymphoma and leukemia often present with non-specific clinical features, but gingival swelling and redness are common (Fig. 4c, d). Advanced cases may involve bone loss and tooth mobility. Unless a patient has a known history of lymphoma or leukemia, the bump on the gums differential diagnosis may include a range of non-neoplastic and neoplastic conditions depending on the extent of disease. Diffuse lesions with gingival redness and swelling may mimic GPA, periodontitis, and hyperplastic gingivitis. More localized swellings can be mistaken for pyogenic granuloma or giant cell epulis.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

The morphological spectrum of lymphomas and leukemia is broad. The key histological feature is the effacement of normal connective tissue by atypical lymphoid/myeloid cells (Fig. 4e). These atypical cells are often arranged in sheets, with high-grade lesions exhibiting obvious mitoses, nuclear and cellular pleomorphism, and necrosis. Indolent B-cell lymphomas, which are less common in the gingiva, may have a more monotonous appearance. Immunohistochemical staining for CD20 and CD3 can highlight the lack of a mixed cell population in lymphomas. Hematopathological consultation is often necessary for definitive subtyping.

High-grade lymphoma/leukemia is less likely to be mistaken for a reactive process. However, surface ulceration or co-existing periodontal disease can obscure the neoplastic infiltrate, emphasizing the importance of careful clinical-pathological correlation in the bump on the gums differential diagnosis.

Osteosarcoma and Chondrosarcoma

Epidemiology

Osteosarcoma accounts for approximately 1% of all head and neck cancers, and the jawbones are the fourth most common site for osteosarcoma. Head and neck osteosarcoma occurs at a later age than peripheral osteosarcoma, with a median age of 36 years. Chondrosarcomas are rare, accounting for a small percentage of all head and neck neoplasms and chondrosarcomas overall. They typically occur in middle age and are more common in males.

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

The presentation of head and neck osteosarcoma depends on tumor location. Most patients present with a mass, pain, potential paresthesia, and tooth loosening. Radiographically, an ill-defined mixed radiolucent and radiopaque lesion is seen, occasionally with a classic “sunburst” appearance. Chondrosarcoma has a similar clinical picture, with swelling being the primary presentation. Other symptoms are location-specific, such as cranial nerve dysfunction, loose teeth, and pain.

Based on radiology, the clinical bump on the gums differential diagnosis for osteosarcoma may include osteomyelitis. In cases without significant bone destruction, benign cemento-osseous lesions may be considered. The clinical differential for chondrosarcoma may include osteosarcoma or more common malignancies like squamous cell carcinoma.

Histology and Histological Differential Diagnosis

Essential for osteosarcoma diagnosis is the presence of neoplastic bone, characteristically lace-like, woven, and closely associated with tumor cells. Tumor cells exhibit significant pleomorphism and can be epithelioid, plasmacytoid, spindled, or fusiform. Histological subtypes include chondroblastic, fibroblastic, and osteoblastic osteosarcoma.

Chondrosarcoma of the head and neck histologically resembles chondrosarcomas elsewhere, with lobules of blue-grey cartilaginous matrix, potentially separated by fibrous bands and exhibiting calcification (Fig. 4f). They are graded I to III based on cellularity, mitoses, and atypia.

The main histological bump on the gums differential diagnosis for osteosarcoma includes osteoblastoma and chondrosarcoma. Correlation with radiology is helpful, as osteoblastoma should be circumscribed with a sclerotic margin. Differentiating chondrosarcoma from chondroblastic osteosarcoma is crucial due to differing prognoses and treatments. Chondroblastic osteosarcomas can have abundant chondroid components, but malignant osteoid production by mesenchymal cells is diagnostic for osteosarcoma.

Conclusion

The clinical and histological features of gingival lumps are remarkably diverse, encompassing a wide spectrum of pathological entities. This review has outlined these lesions, emphasizing areas of diagnostic challenge and potential pitfalls in the bump on the gums differential diagnosis. As most gingival lumps are reactive, effective communication with referring clinicians is essential to ensure appropriate management, including addressing initiating factors. However, it is crucial to remain vigilant for rarer diagnoses, as some represent significant systemic disease processes extending beyond the gingiva.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.