Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease, a devastating neurodegenerative condition, has seen a doubling in mortality rates over the last three decades, a trend expected to worsen with an aging global population.1 Despite extensive research, effective treatments or preventative measures remain elusive.2 Intriguingly, a groundbreaking study utilizing neuroimaging revealed that London taxi drivers, renowned for their intricate spatial knowledge, exhibit enhanced functional changes in the hippocampus.3 This brain region is not only critical for spatial map creation but also implicated in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis, with the disease process marked by accelerated hippocampal atrophy.456 This observation sparks a compelling question: could occupations demanding frequent spatial processing, like taxi driving and ambulance operation, be linked to a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease mortality?

Driven by this hypothesis, we analyzed population-based mortality data from the United States, incorporating newly available occupation information of deceased individuals. Our aim was to assess Alzheimer’s disease mortality across diverse professions. We specifically hypothesized that occupations requiring consistent real-time spatial and navigational processing, such as taxi and ambulance driving (excluding emergency medical technicians or EMTs), might demonstrate a lower incidence of Alzheimer’s-related deaths compared to other occupations.

Methods

Data Sources

Our study leveraged mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System, encompassing all deaths in the US between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2022. These data, derived from death certificates, include the underlying cause of death, classified using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), and sociodemographic details of the deceased, such as age, sex, race, ethnicity, and education level.7

Death certificates also included a field for ‘usual occupation,’ representing the profession in which the individual spent the majority of their working life. This information, typically provided by a funeral director with input from the deceased’s informant, has been systematically coded to standardized 2010 US Census Bureau occupation codes since 2020, in collaboration with the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.8 Occupation data were available for a vast majority of the US population (approximately 98% in 2020-2022), covering 46 states in 2020, 49 in 2021, and all 50 states and Washington, DC in 2022.

Study Population

Our analysis encompassed 443 distinct occupational groups (detailed in the supplemental appendix). We concentrated on taxi drivers (occupation code 9140) and ambulance drivers (occupation code 9110, excluding EMTs) as representative professions demanding extensive daily navigation with unpredictable, real-time spatial challenges. All other occupations served as a comparison group. Additionally, we examined bus drivers (occupation code 9120), aircraft pilots (9030), and ship captains (9310) as a more specific comparison. These transportation-related roles, while still mobile, rely more on predetermined routes and less on spontaneous navigational processing. We excluded individuals with unknown occupation data (4.8% of the studied population), students in high school or college (occupation code 9070), and occupations with fewer than 250 total deaths per year (indicating rare or emerging professions).

Outcome Measure

The primary outcome was the percentage of deaths within each occupation attributed to Alzheimer’s disease as the underlying cause of death (ICD-10 code G30).

Statistical Analysis

For each occupation, we initially calculated the percentage of deaths due to Alzheimer’s disease and the mean age at death (average life expectancy). We visualized the relationship between these variables to highlight the importance of accounting for age at death, given the age-related increase in Alzheimer’s risk and the consequent lower Alzheimer’s mortality in occupations with shorter life expectancies.9

Subsequently, we employed multivariable logistic regression at the individual level to estimate risk-adjusted percentages of Alzheimer’s-related deaths for each occupation. This adjustment accounted for age at death (using indicator variables for each year of age), sex, race/ethnicity (Black, White, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, Other), and educational attainment (using indicator variables for different levels).

To ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted four sensitivity analyses.[10](#ref-10] First, we repeated the analyses focusing on individuals who died at age 60 years or older, aligning with the typical age range for Alzheimer’s onset and mortality.[11](#ref-11] Second, we broadened the definition of Alzheimer’s mortality to include cases where Alzheimer’s disease was listed as either an underlying or contributing cause of death. Third, we assessed Alzheimer’s mortality among bus drivers, aircraft pilots, and ship captains – transportation occupations with less real-time navigational demands. Fourth, we examined deaths attributed to other forms of dementia not primarily linked to hippocampal pathology: vascular dementia (ICD-10 code F01) and unspecified dementias (F03). This served as a falsification analysis to determine if occupation-specific factors for taxi and ambulance drivers (confounders) broadly affected dementia mortality, suggesting an alternative explanation to hippocampus-mediated changes in Alzheimer’s mortality.12

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 18.0 and MATLAB 2024a. Confidence intervals were set at 95% with an α level of 0.025 in each tail (P≤0.05). The study, utilizing publicly available de-identified data, was deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board oversight at Harvard Medical School.

Patient and Public Involvement

This retrospective observational study did not involve direct patient participation in research question formulation, outcome measure selection, or result interpretation. The study was unfunded, precluding resources for patient and public involvement.

Results

Our study population comprised 8,972,221 individuals with recorded occupational information. Table 1 outlines the characteristics of the population by navigational occupation group. Ambulance drivers exhibited the lowest mean age at death (64.2 years, SD 14.7), followed by taxi drivers (67.8 years, SD 14.5). These occupations were predominantly male, with a more balanced sex distribution among bus drivers. Education levels were generally at or below high school for navigational occupations, except for aircraft pilots who had higher educational attainment.

Table 1: Characteristics of decedents with reported navigational occupation

| Occupation | N | Mean age at death (SD) | % Female | % White | % Black | % Hispanic | % Asian or Pacific Islander | % Other race | % < High school education | % High school education | % Some college education | % College degree or higher |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambulance drivers | 1348 | 64.2 (14.7) | 15.9 | 79.9 | 9.7 | 6.5 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 14.6 | 44.9 | 25.8 | 14.7 |

| Taxi drivers | 16,658 | 67.8 (14.5) | 8.4 | 55.8 | 18.8 | 17.3 | 6.1 | 2.0 | 21.9 | 42.4 | 22.4 | 13.3 |

| Bus drivers | 43,295 | 72.8 (13.1) | 40.8 | 67.8 | 19.2 | 8.9 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 13.3 | 38.1 | 27.2 | 21.4 |

| Aircraft pilots | 8465 | 71.1 (12.2) | 3.3 | 90.3 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 11.7 | 26.5 | 60.0 |

| Ship captains | 4199 | 74.1 (12.0) | 1.2 | 87.5 | 3.2 | 5.2 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 4.9 | 25.1 | 30.5 | 39.5 |

| All occupations | 8,972,221 | 72.7 (15.3) | 37.7 | 75.8 | 12.4 | 8.8 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 11.9 | 29.6 | 27.3 | 31.2 |

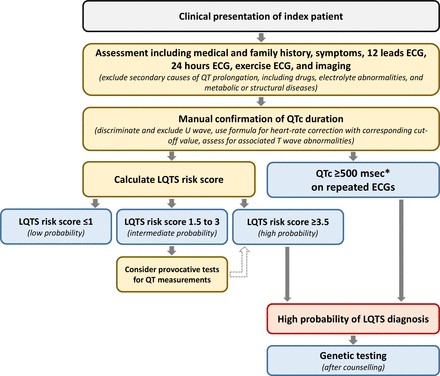

Of the total study population, 3.88% (348,328 out of 8,972,221) had Alzheimer’s disease listed as the underlying cause of death. Unadjusted percentages of Alzheimer’s-related deaths were 1.03% (171/16,658) for taxi drivers and 0.74% (10/1,348) for ambulance drivers. In contrast, bus drivers showed 3.11% (1,345/43,295), aircraft pilots 4.57% (387/8,465), and ship captains 2.79% (117/4,199) (Table 2). Notably, Alzheimer’s deaths were lower for taxi and ambulance drivers compared to other occupations with similar mean ages at death (Figure 1, top graph).

Table 2: Deaths attributed to Alzheimer’s disease by occupation

| Occupation | N Deaths | N Alzheimer’s deaths | % Alzheimer’s deaths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ambulance drivers | 1348 | 10 | 0.74 |

| Taxi drivers | 16,658 | 171 | 1.03 |

| Bus drivers | 43,295 | 1345 | 3.11 |

| Aircraft pilots | 8465 | 387 | 4.57 |

| Ship captains | 4199 | 117 | 2.79 |

| All occupations | 8,972,221 | 348,328 | 3.88 |

After adjusting for age at death, sex, race/ethnicity, and education, ambulance drivers (0.91%, 95% CI 0.35-1.48%) and taxi drivers (1.03%, 95% CI 0.87-1.18%) remained the two occupations with the lowest adjusted percentages of Alzheimer’s deaths out of 443 occupations (Figure 1, middle graph). In contrast, the adjusted percentage for the general population was 1.69% (95% CI 1.66-1.71%), with significantly lower odds ratios for both taxi and ambulance drivers (Figure 1, bottom graph; odds ratio 0.56, 95% CI 0.48-0.65 for combined categories relative to chief executives).

Sensitivity analyses consistently showed that ambulance and taxi drivers had the lowest proportional Alzheimer’s mortality when restricting analysis to deaths at age 60+ (supplemental figure 1) and when Alzheimer’s was considered as either an underlying or contributing cause of death (Figure 2). This pattern of reduced Alzheimer’s mortality was not observed in other transportation occupations with fewer navigational demands (Figure 3). Aircraft pilots and ship captains ranked 4th and 23rd highest in adjusted Alzheimer’s mortality, while bus drivers ranked 263rd out of 443 occupations. The adjusted percentage for bus drivers was 1.65% (95% CI 1.56-1.74%) (Figure 4).

Discussion

Key Observations

This extensive US population-based study revealed a significant finding: taxi and ambulance drivers, professions heavily reliant on navigational memory and spatial skills, exhibited the lowest Alzheimer’s disease mortality rates among all occupations studied. A potential explanation for this intriguing observation is that these occupations foster neurological adaptations, possibly within the hippocampus or other brain regions, that confer protection against Alzheimer’s disease risk.

Our study was initially inspired by research on hippocampal changes in London taxi drivers.12 While the cognitive demands on London taxi drivers are exceptional, requiring extensive training and testing of city navigation (“The Knowledge”), the fundamental aspects of spatial navigation and frequent complex navigational tasks are also integral to the roles of US taxi and ambulance drivers, particularly in past decades. Supporting our findings, a subsequent study on London bus drivers did not find similar hippocampal enhancements, possibly due to the predictable nature of bus routes.3 If a hypothetical link exists between hippocampal changes in taxi drivers and reduced future Alzheimer’s mortality, our results among US taxi and bus drivers align with hippocampal findings in their London counterparts.

Strengths and Limitations

It is crucial to acknowledge several limitations in our study design that preclude definitive causal conclusions and suggest alternative explanations, including unmeasured confounding factors of biological, social, or administrative nature. Firstly, selection bias is a potential concern. Individuals inherently more prone to developing Alzheimer’s disease might be less likely to choose or remain in demanding, memory-intensive driving occupations such as taxi and ambulance driving. This could mean that the observed lower Alzheimer’s mortality in these professions is not due to a protective job effect, but rather because individuals susceptible to the disease may have self-selected out of these roles. However, Alzheimer’s symptoms typically manifest after typical working years, with only 5-10% of cases classified as early onset (before age 65).1114 While subtle symptoms might emerge earlier, they would likely occur after an individual has established their ‘usual occupation,’ mitigating significant attrition from navigational jobs due to early Alzheimer’s development. Furthermore, even if lifelong taxi driving attracts individuals with superior spatial processing abilities, our findings still suggest a noteworthy correlation between robust spatial processing skills and reduced Alzheimer’s risk.

Secondly, our study assumes that an individual’s ‘usual occupation’ at death reflects a significant portion of their working life, despite the commonality of multiple job changes. However, ‘usual occupation’ has been demonstrated as a reliable proxy for current occupation.15 To the extent that classification errors exist, they are more likely to misclassify individuals with substantial navigational job experience into other occupational categories. Such misclassification would likely underestimate, rather than overestimate, the differences between navigational and non-navigational occupations. Moreover, this bias is unlikely to selectively affect Alzheimer’s disease mortality without also impacting other forms of dementia.

Thirdly, death certificates may underreport Alzheimer’s disease deaths, and this underreporting could vary by occupation. The preserved navigational memory in taxi and ambulance drivers might lead clinicians to underestimate Alzheimer’s possibility in these patients, resulting in a lower reported proportion of Alzheimer’s deaths. Similarly, taxi or ambulance drivers might be reluctant to seek medical evaluation for cognitive symptoms due to job security concerns, potentially leading to underdiagnosis. However, such diagnostic biases would likely affect mortality reporting for all dementias, not just Alzheimer’s, and would need to be specific to taxi and ambulance drivers to explain our findings, and not extend to other transportation roles like bus drivers, pilots, or ship captains.

Fourthly, mortality record analyses are prone to underestimating Alzheimer’s prevalence, as its contribution to mortality is complex and more immediate causes may be listed on death certificates. However, any diagnostic error in our study is unlikely to differ systematically across occupational groups. Furthermore, our consistent results when considering Alzheimer’s as a contributing cause of death, and the absence of similar findings for other dementia types, strengthens our specific findings related to Alzheimer’s.

Finally, our study analyzed proportions of deaths attributed to Alzheimer’s rather than standardized mortality rates, due to the lack of reliable population-based denominators by occupation. While proportional mortality analyses do not provide information on population risk, with careful selection of control groups and adjustment for factors influencing competing risks (e.g., age, sex, social class), they can still serve as valuable indicators of disease frequency variations across different occupations.16[17](#ref-17]

Conclusion

Our large-scale epidemiological findings generate compelling questions about the relationship between taxi and ambulance driving and Alzheimer’s disease mortality. While these results suggest a possible link between the demands of these occupations and a reduced Alzheimer’s risk, our study design cannot establish a causal relationship between occupation and Alzheimer’s mortality or hippocampal neurological changes. We interpret these findings as hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive. Further research is essential to determine definitively if the spatial cognitive demands of these professions influence Alzheimer’s disease risk and whether specific cognitive activities can offer potential preventative benefits.

What is already known on this topic

- The hippocampus is among the first brain regions to undergo atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease, contributing to significant cognitive decline as the disease progresses.

- The hippocampus is crucial for spatial memory and navigation, and studies have shown it to be more developed in taxi drivers compared to the general population.

What this study adds

- This comprehensive analysis of nearly all US death certificates reveals that taxi and ambulance drivers, whose occupations require frequent spatial and navigational processing, have the two lowest risk-adjusted percentages of deaths attributed to Alzheimer’s disease.

- Our findings suggest that frequent navigational and spatial processing tasks, as performed by taxi and ambulance drivers, might offer some protection against Alzheimer’s disease.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

This study utilized publicly available data and was deemed exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at Harvard Medical School.

Data availability statement

Data are publicly available.

Footnotes

- Contributors: All authors contributed to study design, data collection, management, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation. ABJ supervised the study and is the guarantor.

- Funding: CMW received funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant #K08HS029197), unrelated to this project. The study itself was unfunded.

- Competing interests: Authors declare no competing interests except consulting fees and income unrelated to this work as detailed in the ICMJE disclosure form.

- Transparency: The lead author affirms the manuscript’s honesty, accuracy, and transparency.

- Dissemination: Results will be disseminated via press releases, news articles, and an opinion piece.

- Provenance and peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ This is an Open Access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license.