Introduction

The use of psychotropic medications has seen a significant rise over the last two decades, a trend largely attributed to increased prescriptions from physicians who are not psychiatrists. In the United States, it’s estimated that a considerable portion of adults are using these medications. This increase, coupled with the approval of new psychotropic drugs, highlights the significant role these medications play in healthcare, representing a notable proportion of overall health costs.

However, an unexpected trend has emerged: a substantial number of psychotropic prescriptions are being issued to patients without any documented psychiatric diagnosis. This is not just about whether the diagnosis aligns with the approved uses of the drug, but the more fundamental issue of prescribing psychotropics when no psychiatric condition is officially recognized. Studies have indicated that a large proportion of antidepressant prescriptions, for instance, are given without an accompanying psychiatric diagnosis. This pattern is observed across different healthcare settings and populations, raising serious questions about current prescribing habits.

This practice is concerning for several reasons. Firstly, prescribing without a clear diagnostic indication could suggest off-label use or inappropriate application of medications. These drugs might not be effective for the actual problem, and they carry the risk of adverse effects. Many psychotropics have anticholinergic properties, which can lead to complications, especially in older adults. Furthermore, potent medications like antipsychotics demand careful administration due to risks of sedation, metabolic issues, and even mortality in vulnerable groups. Another critical concern is the potential for misuse and abuse, particularly with addictive psychotropic medications when prescribed without a valid psychiatric diagnosis.

Previous research in this area has faced limitations, such as not differentiating between new prescriptions and renewals, focusing on specific drug classes like antidepressants only, and having a limited scope in terms of the populations studied or the time frame of the data. To address these gaps, a study was conducted using data from outpatient visits where new prescriptions for antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anxiolytics were initiated. This study aimed to determine the national rates of such prescriptions without a psychiatric diagnosis from 2006 to 2015, identify which medical specialties and medication classes were most associated with this practice, and explore demographic and clinical factors linked to initiating new psychotropic prescriptions lacking a psychiatric diagnosis. This research stands as a crucial pharmacoepidemiologic investigation into the trends of initiating psychotropic prescriptions without a documented psychiatric diagnosis in outpatient settings, providing essential data for future monitoring and policy development to encourage more responsible prescribing practices.

Methods

Data Source and Study Sample

The data for this study was derived from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NAMCS) spanning 2006 to 2015. NAMCS, administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is a nationally representative survey of outpatient physician visits in the U.S. It offers a comprehensive view of outpatient medical care across the nation. The study focused on adult patients aged 18 and older who were prescribed new psychotropic medications. Initially, the sample included 9,467 unweighted observations. After excluding cases with missing covariate data, the final sample size comprised 8,618 observations. The use of publicly available, de-identified data meant this study was exempt from full Institutional Review Board review at Yale School of Medicine. Detailed information about NAMCS, including survey methodologies, questionnaires, and datasets, is accessible on the NAMCS website.

Measures

Psychotropic Medications

NAMCS records medications prescribed during visits, ranging from eight medications in early years to thirty in later years of the study period. To maintain consistency, the study analyzed the first eight medications listed for each visit. A key variable in NAMCS indicates whether a medication is newly prescribed, continued, or of unknown status. The study defined “initiation” of psychotropic treatment as visits where a new psychotropic medication was prescribed. Psychotropic medications were categorized into three main classes: antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anxiolytics, based on their generic names.

- Antipsychotics: This class included medications like haloperidol, risperidone, and quetiapine, among others, typically used to treat psychotic disorders.

- Antidepressants: This category encompassed drugs such as sertraline, fluoxetine, and venlafaxine, primarily used for depressive disorders and sometimes anxiety.

- Anxiolytics: This group included medications like alprazolam, lorazepam, and diazepam, commonly prescribed for anxiety and related conditions.

Mental Health Conditions

NAMCS records up to three diagnoses per visit using ICD-9-CM codes. The study focused on psychiatric diagnoses categorized into five groups:

- Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

- Depressive disorders other than MDD

- Anxiety disorders

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Other psychiatric disorders, including dementia, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorders, among others.

Substance use disorders were also examined, covering alcohol, opiates, cocaine, cannabis, barbiturates, amphetamines, and hallucinogens. Additionally, the study identified non-psychiatric FDA-approved indications for psychotropic drugs, such as seizures, insomnia, migraine, pain, and narcolepsy, to account for prescriptions potentially given for non-psychiatric reasons.

Covariates

Several demographic and clinical covariates were considered:

- Demographics: Age (18-44, 45-64, 65-74, 75+), gender, race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other), region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), primary payment source (Private, Medicare, Medicaid, Other).

- Visit Characteristics: Reason for visit (acute problem, routine chronic problem, preventive care, pre- or post-surgery), number of repeat visits in the past year (none, 1-2, 3-5, 6+), physician specialty (primary care, psychiatry, other), metropolitan statistical area (MSA) status, receipt of psychotherapy or mental health counseling, time spent with the doctor (<15 min, 15-20 min, 21-30 min, >30 min).

- Health Status: Number of chronic conditions (none, 1, 2-3, 4+), total number of medications documented (0-3, 4-5, 6+).

The number of chronic conditions was derived from 14 conditions tracked by NAMCS, such as arthritis and diabetes.

Data Analysis

The analysis began by comparing characteristics of visits where new psychotropic prescriptions were initiated, distinguishing between those with and without a psychiatric diagnosis. Risk ratios were used to quantify the effect size due to the large sample size, where standard significance testing could be misleading. A risk ratio of 1.0 indicated no difference, while values greater than 1.0 suggested a higher likelihood of psychotropic prescription without a diagnosis.

Next, the study estimated trends in psychotropic prescription initiation without a psychiatric diagnosis from 2006 to 2015, further broken down by psychotropic class. Finally, multivariable-adjusted logistic regression was employed to identify demographic and clinical factors independently associated with receiving a new psychotropic prescription without a psychiatric diagnosis. This regression analysis only included variables with risk ratios significantly above 1.20 or below 0.80 from the bivariate analysis to focus on clinically meaningful associations. Stata 15.1 was used for all analyses, incorporating survey commands to account for NAMCS’s complex sampling design.

Results

Selected Characteristics of the Sample

Between 2006 and 2015, psychotropic prescriptions were given in 19.4% of all adult outpatient visits in the U.S. Notably, in 60.4% of visits where a new psychotropic medication was initiated, no psychiatric diagnosis was recorded. Tables 1 and 2 detail the demographic and clinical characteristics of these visits. Younger adults (18-64 years) constituted the majority (74.9%) of visits. However, older adults (65+) showed a higher risk ratio (1.47 or greater) of receiving psychotropic prescriptions without a psychiatric diagnosis compared to younger adults (18-44).

Physician specialty was a critical factor. Visits to psychiatrists had a remarkably low risk ratio (0.04) of resulting in a psychotropic prescription without a psychiatric diagnosis compared to primary care visits. In contrast, visits to non-psychiatric specialists had a significantly higher risk ratio (1.57) for such prescriptions when compared to primary care. The number of concomitant medications also played a role; patients prescribed three to five or six or more medications had higher risk ratios (1.39 and 1.76, respectively) of receiving a psychotropic prescription without a psychiatric diagnosis compared to those on fewer medications.

Table 1. Weighted selected characteristics of US adults aged 18 or older with initiation of psychotropic prescriptions in office‐based outpatient settings, 2006‐2015 NAMCS

| All visits (N) | Column percentage of all visits | Without a psychiatric diagnosis (n) | Row percentage of no psychiatric diagnosis of all visits (%) | Risk ratio (reference condition = 1.00) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size (row %) | ||||

| Unweighted sample | 8618 | 100.0 | 5227 | 60.7 |

| Weighted visits | 22 498 475 | 100.0 | 13 584 867 | 60.4 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–44 | 9 067 847 | 32.9 | 4 475 391 | 49.4 |

| 45–64 | 8 767 848 | 42.0 | 5 711 662 | 65.1 |

| 65–74 | 2 510 135 | 13.4 | 1 819 667 | 72.5 |

| 75+ | 2 152 644 | 11.6 | 1 578 147 | 73.3 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 7 527 092 | 31.9 | 4 998 501 | 66.4 |

| Female | 14 971 383 | 68.1 | 10 270 274 | 68.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 17 295 675 | 76.8 | 10 427 975 | 60.3 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 2 028 931 | 8.8 | 1 195 120 | 58.9 |

| Hispanic | 2 225 878 | 10.3 | 1 393 968 | 62.6 |

| Othera | 947 990 | 4.2 | 567 804 | 59.9 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 4 148 797 | 18.4 | 2 452 795 | 59.1 |

| Midwest | 4 528 529 | 19.9 | 2 720 545 | 60.1 |

| South | 9 073 191 | 40.4 | 5 574 362 | 61.4 |

| West | 4 747 958 | 21.4 | 2 837 166 | 59.8 |

| Source of payment | ||||

| Private | 13 193 467 | 58.8 | 7 986 879 | 60.5 |

| Medicare | 5 052 891 | 25.2 | 3 426 054 | 67.8 |

| Medicaid | 2 004 322 | 7.4 | 1 011 244 | 50.5 |

| Otherb | 2 247 796 | 8.5 | 1 160 690 | 51.6 |

| Reason for visit | ||||

| Acute problem | 8 325 426 | 37.2 | 5 562 728 | 66.8 |

| Routine chronic problem | 10 532 579 | 46.4 | 5 432 677 | 51.6 |

| Preventive care | 2 941 596 | 13.3 | 1 927 061 | 65.5 |

| Pre‐ or post‐surgery | 698 875 | 3.1 | 662 401 | 94.8 |

| Repeat of visits in the past 12 mo | ||||

| 0 visit | 1 531 633 | 7.2 | 981 289 | 64.1 |

| 1–2 visits | 8 217 303 | 36.4 | 4 943 891 | 60.2 |

| 3–5 visits | 7 015 176 | 31.6 | 4 291 595 | 61.2 |

| 6+ visits | 5 734 363 | 24.8 | 3 368 093 | 58.7 |

| Physician specialty | ||||

| Primary care | 13 343 476 | 56.4 | 7 660 805 | 57.4 |

| Psychiatry | 2 632 497 | 0.4 | 56 044 | 2.1 |

| Otherc | 6 522 502 | 43.2 | 5 868 018 | 90.0 |

| Metropolitan statistical area (MSA) | ||||

| MSA | 19 877 253 | 89.0 | 12 092 027 | 60.8 |

| Non‐MSA | 2 621 222 | 11.0 | 1 492 840 | 57.0 |

| Mental health counseling and psychotherapy | ||||

| No | 20 249 204 | 99.0 | 13 446 934 | 66.4 |

| Yes | 2 249 271 | 1.0 | 137 933 | 6.1 |

| Time spent with doctor | ||||

| <15 min | 3 397 901 | 15.0 | 2 042 805 | 60.1 |

| 15–20 min | 10 238 764 | 47.3 | 6 425 729 | 62.8 |

| 21–30 min | 5 187 371 | 23.6 | 3 200 891 | 61.7 |

| >30 min | 3 674 439 | 14.1 | 1 915 442 | 52.1 |

| Multiple chronic conditions | ||||

| None | 5 804 526 | 30.6 | 4 151 811 | 71.5 |

| 1 | 7 743 151 | 28.6 | 3 882 490 | 50.1 |

| 2–3 | 7 101 673 | 30.9 | 4 202 545 | 59.2 |

| 4+ | 1 849 125 | 9.9 | 1 348 020 | 72.9 |

| Number of medications | ||||

| 0–2 | 7 854 367 | 25.8 | 3 498 788 | 44.5 |

| 3–5 | 8 610 092 | 39.3 | 5 342 083 | 62.0 |

| 6+ | 6 034 016 | 34.9 | 4 743 997 | 78.6 |

aAsians, American Indian/Alaska Natives (AIANs), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islanders (NHOPI), and other mixed racial groups.

bWorker’s compensation, self‐pay, no charge, and others.

cGeneral surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, orthopedic surgery, cardiovascular diseases, dermatology, urology, neurology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, and others.

Regarding clinical characteristics (Table 2), FDA-approved non-psychiatric indications for psychotropic use, such as insomnia, were associated with a higher risk ratio (1.46) for prescriptions without a psychiatric diagnosis. Among psychotropic drug classes, antipsychotics and antidepressants had lower risk ratios (0.39 and 0.77, respectively) for prescriptions without a psychiatric diagnosis, while anxiolytics showed a slightly elevated risk ratio (1.19).

Table 2. Weighted characteristics of initiating psychotropic medication use without a psychiatric diagnosis in US adults aged 18 or in office‐based outpatient settings, 2006‐2015 NAMCS

| All visits (N) | Column percentage of all visits (%) | Without a psychiatric diagnosis (n) | Row percentage of no psychiatric diagnosis of all visits (%) | Column percentage of no psychiatric diagnosis of all visits (%) | Bivariate risk ratio for having no psychiatric diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | ||||||

| Unweighted sample | 8618 | 100.0 | 5227 | 60.7 | ||

| Weighted visits | 22 498 475 | 100.0 | 13 584 867 | 60.4 | ||

| FDA‐approved non‐psychiatric indications | 3 165 849 | 14.1 | 2 182 922 | 69.0 | 16.1 | 1.46 |

| Total number of psychotropics prescribed | ||||||

| One | 4 445 464 | 21.3 | 2 891 614 | 65.0 | 21.3 | 1.22 |

| Two | 12 645 752 | 62.2 | 8 449 328 | 66.8 | 62.2 | 1.32 |

| Three | 1 889 445 | 6.3 | 859 357 | 45.5 | 6.3 | 0.55 |

| Four or more | 3 517 814 | 10.2 | 1 384 568 | 39.4 | 10.2 | 0.43 |

| Psychotropic class | ||||||

| Antipsychotic | 2 121 106 | 5.9 | 795 923 | 37.5 | 5.9 | 0.39 |

| Antidepressant | 14 226 981 | 56.5 | 7 671 438 | 53.9 | 56.5 | 0.77 |

| Anxiolytic | 10 802 382 | 51.3 | 6 968 650 | 64.5 | 51.3 | 1.19 |

| Overall | 27 150 469 | 15 436 011 |

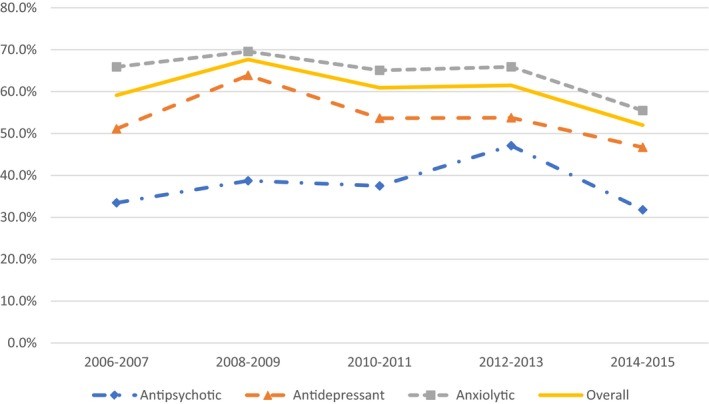

Trends of Psychotropic Prescription Initiation Without a Psychiatric Diagnosis

Figure 1 illustrates the trends in new psychotropic prescriptions initiated without a psychiatric diagnosis from 2006 to 2015. Overall, the rate increased from 59.1% in 2006-2007 to 67.7% in 2008-2009, before decreasing to 52.0% in 2014-2015. Anxiolytics consistently showed the highest rate of prescription without a psychiatric diagnosis over this period, peaking at 69.6% in 2008-2009 and decreasing to 55.5% by 2014-2015. Antipsychotics consistently had the lowest rate of prescription without a psychiatric diagnosis throughout the study period.

Figure 1.

Trends in Psychotropic Prescriptions Without Psychiatric Diagnosis (2006-2015)

Trends in Psychotropic Prescriptions Without Psychiatric Diagnosis (2006-2015)

Initiation of psychotropic prescription without a psychiatric diagnosis among US adults aged 18 or older, 2006‐2015 NAMCS [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Overall psychotropic prescriptions increased from 59.1% in 2006‐2007 to 67.7% in 2008‐2009 and then decreased to 52.0% in 2014‐2015 (P = 0.041). Individual psychotropic class did not show significant time trends from 2006 to 2015.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis

Table 3 presents the adjusted odds ratios from the multivariable logistic regression. It highlights factors independently associated with receiving a new psychotropic medication without a concurrent psychiatric diagnosis. Older age was a significant predictor; for instance, adults aged 45-64 had 1.57 times higher odds of not having a psychiatric diagnosis compared to those aged 18-44. Physician specialty remained a critical factor: psychiatrist visits were associated with significantly lower odds (OR = 0.02) of lacking a psychiatric diagnosis, while non-psychiatric specialist visits had 6.90 times greater odds compared to primary care visits. Having three or more concomitant medications was also linked to higher odds of not having a psychiatric diagnosis.

Table 3. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) of no psychiatric diagnosis among adults ages 18 or older with initiation of psychotropic prescription in office‐based outpatient settings by psychotropic class, 2006‐2015 NAMCS

| (Reference group in parentheses) | Overall | Antipsychotic | Antidepressant | Anxiolytic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| Age (18–44) | ||||

| 45–64 | 1.57*** | 1.30–1.90 | 1.39 | 0.73–2.67 |

| 65+ | 1.68*** | 1.30–2.18 | 2.26 | 0.78–6.53 |

| Physician specialty (primary care) | ||||

| Psychiatry | 0.02*** | 0.01–0.04 | 0.01*** | 0.00–0.06 |

| Othera | 6.90*** | 5.38–8.86 | 3.23** | 1.61–6.47 |

| Number of medications (0-2) | ||||

| 3–5 | 2.20*** | 1.79–2.71 | 1.81 | 0.85–3.84 |

| 6+ | 3.38*** | 2.44–4.69 | 4.41*** | 2.08–9.37 |

| FDA‐approved non‐psychiatric indications (no) | ||||

| Yes | 1.38** | 1.11–1.72 | 0.52 | 0.20–1.37 |

| Psychotropic use | ||||

| Antipsychotic (no) | 1.00 | Reference | — | — |

| Antidepressant (no) | 1.22 | 0.77–1.88 | 0.48* | 0.25–0.95 |

| Anxiolytic (no) | 1.46 | 0.93–2.29 | 0.68 | 0.32–1.45 |

| Sample size | ||||

| Unweighted sample | 9129 | 899 | ||

| Weighted visits | 23 964 669 | 2 121 106 |

aGeneral surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, orthopedic surgery, cardiovascular diseases, dermatology, urology, neurology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, and others.

*P < 0.001; P < 0.01; P* < 0.05

Having FDA-approved non-psychiatric indications, including insomnia, increased the odds of not having a psychiatric diagnosis by 1.38 times. When examining psychotropic drug classes, antidepressants and anxiolytics showed higher odds of being prescribed without a psychiatric diagnosis compared to antipsychotics, although these differences were not statistically significant in the overall model.

Stratified analyses by psychotropic class revealed consistent patterns for age, physician specialty, and number of medications. For antidepressants, having FDA-approved non-psychiatric indications significantly increased the odds of prescription without a psychiatric diagnosis (OR = 1.47). Across all classes, being prescribed other psychotropic medications was associated with lower odds of lacking a psychiatric diagnosis. For example, for antidepressant prescriptions, having an anxiolytic prescription reduced the odds of lacking a psychiatric diagnosis by 0.52 times.

Discussion

This study provides crucial insights into the practice of initiating new psychotropic prescriptions without a documented psychiatric diagnosis in U.S. outpatient settings from 2006 to 2015. Approximately 60.4% of new psychotropic prescriptions were initiated without any recorded psychiatric diagnosis, a rate consistent with previous studies. This persistently high rate raises concerns about the evidence-based foundation and appropriateness of psychotropic medication use in many instances.

The study’s findings highlight significant variations across psychotropic drug classes. Anxiolytics were most frequently prescribed without a psychiatric diagnosis, echoing previous research. This could be attributed to these medications being prescribed for symptoms rather than diagnosed conditions or potentially influenced by direct-to-consumer advertising, which heavily promotes psychotropics. It’s noted that patient requests, possibly driven by advertising, can lead to a substantial proportion of psychotropic prescriptions.

Multivariable analysis revealed older adults and visits to non-psychiatric specialists as key factors associated with higher odds of psychotropic prescriptions without a psychiatric diagnosis. The increased risk for older adults is particularly concerning given their vulnerability to medication side effects due to multimorbidity and polypharmacy. Non-psychiatric specialists showing a higher likelihood of prescribing without diagnosis aligns with previous findings and suggests these physicians might be addressing milder mood or anxiety symptoms that do not meet formal psychiatric disorder criteria. However, this practice raises concerns about proper documentation and potential liability risks for non-psychiatrists. Thorough documentation is crucial for defending against malpractice claims, emphasizing the need for non-psychiatrists to exercise caution and diligence in psychotropic prescribing and documentation.

The association between a higher number of concomitantly prescribed medications and psychotropic prescriptions without a psychiatric diagnosis also warrants attention. While some medication combinations are clinically justified, many lack evidence of efficacy and may increase the risk of adverse drug interactions. The lower likelihood of antipsychotics being prescribed without a diagnosis, compared to other psychotropic classes, might be due to FDA boxed warnings and their more frequent prescription by psychiatrists. Furthermore, the study found that medications with FDA-approved non-psychiatric uses, like antidepressants and anxiolytics for insomnia, were more likely to be prescribed without a psychiatric diagnosis, highlighting the potential for these drugs to be used for less-validated reasons.

Clinical and Policy Implications

These findings have important implications for clinical practice and healthcare policy. Firstly, there is a clear need for enhanced training in psychotropic prescribing for non-psychiatrist physicians. While diagnostic stigma might contribute to under-documentation of psychiatric diagnoses, ensuring appropriate psychotropic use and minimizing medical malpractice risks necessitates that prescribing practices align more closely with clinical evidence and approved indications, especially outside of psychiatric settings. Secondly, insurers could play a role by restructuring drug formulary policies to incentivize diagnosis-based prescribing. For example, differential cost-sharing based on whether a psychiatric diagnosis is documented could encourage more appropriate prescribing. Additionally, incorporating adherence to orthodox prescribing practices into quality of care performance models could motivate physicians to be more careful when initiating psychotropic prescriptions.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered. NAMCS data excludes visits to hospital-affiliated clinics and emergency departments and phone prescriptions, potentially missing a segment of outpatient psychotropic prescriptions. Data collection relies on physician surveys and chart reviews, which might suffer from incomplete documentation. NAMCS also limits the number of recorded diagnoses, potentially leading to underreporting of psychiatric diagnoses in complex cases. The lack of dosing information in NAMCS also restricts the ability to fully assess the appropriateness of psychotropic use. Finally, the study’s criterion of “any” psychiatric diagnosis does not address the appropriateness of the diagnosis itself.

Despite these limitations, this study significantly contributes to understanding the scope and correlates of new psychotropic medication initiations without a concurrent psychiatric diagnosis. It underscores the critical need for aligning prescribing practices, particularly among non-psychiatrists, with clinical evidence and established standards of care to ensure appropriate and safe medication use.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and none were reported. All research procedures performed in this study are in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board at Yale University School of Medicine (#2000021850).

Supporting information

Click here for additional data file. (1.6MB, pdf)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: Rhee received funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (#T32AG019134). The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclaimers: Publicly available data were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Analyses, interpretation, and conclusions are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Division of Health Interview Statistics or NCHS of the CDC.

Rhee TG, Rosenheck RA. Initiation of new psychotropic prescriptions without a psychiatric diagnosis among US adults: Rates, correlates, and national trends from 2006 to 2015. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:139–148. 10.1111/1475-6773.13072

REFERENCES

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Click here for additional data file. (1.6MB, pdf)