Julie N. from Michigan City, Indiana, a vibrant woman in her early 40s, found herself sinking into an overwhelming darkness. As a mother, wife, and nurse, her life, once full, became an unbearable weight. Depression, a stranger to her until then, gripped her so tightly that getting out of bed felt like an insurmountable task.

Her appetite vanished, sleep became a luxury, and her weight plummeted from 130 to 105 pounds. Days blurred into a hazy fog, devoid of joy or energy. “I wasn’t interested in doing things I normally enjoyed,” she recalls. “Looking back now, I can see I was struggling with depression.” This period of intense low mood began at least a year before her breast cancer diagnosis in 2008 at the age of 45. The diagnosis itself deepened her despair, pushing her to attempt suicide twice.

Cancer’s impact is all-encompassing, altering everything from physical appearance to the fundamental drive to eat. It can rob individuals of their identity, their livelihoods, and profoundly diminish their quality of life, and sometimes, life itself. Cancer treatments, while life-saving, bring their own harsh side effects – nausea, debilitating fatigue, and hair loss are just a few. Therefore, it’s tragically unsurprising that depression rates among cancer patients are three to five times higher than in the general population.

Dr. Michael Irwin, a distinguished professor of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine, explains the biological underpinnings of this connection. “Cancer produces profound biological effects on the body that can alter behavior,” he states. “When immune cells mobilize to fight cancer, they trigger an inflammatory response throughout the body. This inflammation can significantly contribute to the development of depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as disruptive sleep patterns.”

While sadness and feelings of hopelessness may seem like a natural emotional response to a cancer diagnosis, a growing body of research points to a much deeper, more insidious link. This research suggests that depression isn’t just a reaction to cancer; it may actually be an intrinsic part of the disease process itself, potentially even preceding the diagnosis.

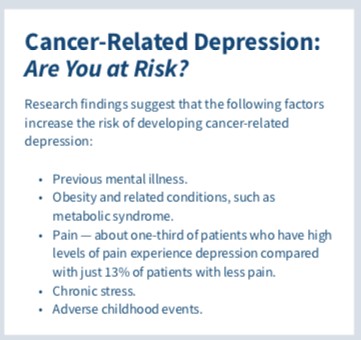

Scientists are diligently working to pinpoint who is most vulnerable to developing cancer-related depression, which cancer types exhibit the strongest correlation with emotional distress, and crucially, whether effectively treating depression can improve cancer outcomes.

The Role of Inflammation

For over a decade, research has steadily unveiled a robust link between cancer and emotional health challenges. Scientists are increasingly exploring theories that go beyond the straightforward notion that “being diagnosed with cancer is depressing.” Dr. Andrew H. Miller, a professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Emory University School of Medicine, specializing in behavioral immunology, sheds light on this. “There are numerous psychological factors that understandably come into play when someone learns they have cancer,” he acknowledges. “However, what many people don’t realize is that cancer itself can initiate the release of molecules that travel to the brain and directly induce depressive symptoms, even before the cancer is formally diagnosed.”

Inflammation emerges as a central player in this intricate relationship. When the body’s immune system is activated, attempting to combat cancer cells, it unleashes a surge of inflammatory substances called cytokines. Even moderately elevated levels of these immune cytokines have been demonstrably linked to cognitive difficulties and emotional disturbances. Therefore, it becomes clear how triggering the body’s innate immune response to cancer can elevate the risk of developing depression alongside the physical illness.

“Approximately 30% of individuals with typical depression, who are not medically ill, exhibit increased inflammation as a component of their depression. In the cancer patient population, this percentage climbs closer to 50%,” Miller explains.

Once cancer activates the immune system, the body prioritizes energy conservation. The brain receives signals to slow down, redirecting available resources to combat the disease. This physiological shift impacts cognitive function, leading to impaired concentration, reduced processing speed, and the subjective experience of feeling depressed. “This protective response is evolutionarily ingrained. It represents how your immune system and brain collaboratively respond to the presence of illness,” Miller elaborates.

Remarkably, even administering immune cytokines to individuals in laboratory settings can swiftly induce a “sickness behavior syndrome” within minutes. This syndrome manifests as fatigue, anxiety, cognitive impairment, and disruptions in appetite and sleep – a cluster of symptoms strikingly similar to those observed in individuals suffering from clinical depression.

Pre-Diagnosis Depression: An Early Warning Sign?

While depression is the most extensively studied psychiatric disorder in the context of cancer, studies on its prevalence yield a wide range of results. Reported depression rates in cancer patients fluctuate from as low as 3% to as high as nearly 60%. Notably, these rates tend to be highest among individuals diagnosed with cancers that carry poorer prognoses, such as lung, aggressive breast, and pancreatic cancers.

As far back as 1967, researchers observed that up to half of pancreatic cancer patients experienced depressive symptoms prior to their diagnosis. More recent reviews of existing literature, one from 1993 and another from 2015, corroborated these findings, reporting that 33%-45% of pancreatic cancer patients experienced psychiatric symptoms even before the onset of noticeable physical symptoms.

“Pancreatic cancer appears to be particularly linked to pre-diagnosis depression, likely because the pancreas plays a crucial role in secreting mood-stabilizing hormones, neurotransmitters, and digestive enzymes. Furthermore, pancreatic cancer is often a rapidly progressing cancer that triggers a significant inflammatory response,” suggests Irwin. Lung cancer also frequently demonstrates a strong association with depressive symptoms. A 2017 study published in Psychiatric Investigations focusing on ten common cancer types in South Korea, revealed that depression was most prevalent among lung cancer patients (11%). Gender-specific cancers, including breast, cervical, and prostate cancers, also showed relatively elevated depression prevalence rates, ranging between 8% and 9%.

Post-Diagnosis Depression: The Emotional Toll

Holly Kapherr Alejos from Orlando, Florida, received a breast cancer diagnosis – invasive ductal carcinoma – at just 34 years old. Newly married, settling into a new job, and planning to start a family, the diagnosis was a devastating shock. “I took care of my body. I ate healthy foods. I didn’t smoke or drink excessively. I did everything you’re supposed to do to avoid a major health crisis,” she recounts. “And yet, I had cancer at an age when I shouldn’t have to face a life-threatening diagnosis.”

Alejos initially suppressed her emotions and entered a state of “autopilot,” navigating a demanding schedule of appointments with oncologists, fertility specialists, and plastic surgeons. Diagnosed in April 2018, she underwent in vitro fertilization in late April, breast cancer surgery in May, and commenced six cycles of chemotherapy in June, followed by 20 rounds of radiation.

It wasn’t until she completed her final radiation treatment in December 2018 that her carefully managed emotions overwhelmed her. “I was angry, resentful, and deeply sad. By the end of March, I was crying every day, and I knew I desperately needed to get help,” Alejos explains.

Alejos’ experience is far from isolated. Studies focusing on women with breast cancer reveal a significant correlation between chemotherapy treatment and an increased risk of depression. Nearly two-thirds of breast cancer patients experience some form of mood disorder, and research indicates that emotional disturbances affect a similar proportion of patients across various cancer types.

However, depression’s impact extends far beyond emotional distress. Compelling evidence demonstrates that depressed cancer patients have a significantly shorter lifespan compared to their counterparts who maintain a more positive emotional state. A study following 205 cancer patients over 15 years, published in Psychosomatic Medicine in 2003, identified depressive symptoms as the most consistent psychological predictor of reduced survival time.

Further research links depression and anxiety to poorer treatment outcomes, difficulties in making informed treatment decisions, reduced adherence to complex and lengthy treatment regimens, and prolonged hospital stays. While non-adherence to treatment partially explains the increased mortality risk in depressed patients, studies suggest that chronic stress responses – and the resulting persistent inflammation – may also promote tumor growth.

Paradoxically, cancer treatment itself can exacerbate depression. “When you treat cancer, whether with chemotherapy or radiation, you are effectively killing tumor cells, but you are also inevitably damaging healthy cells,” Miller points out. “This extensive cellular damage triggers incredibly high levels of inflammation, which can reach the brain and contribute to depressive symptoms.” This creates a negative feedback loop, where the flood of pro-inflammatory cytokines can further stimulate cancer growth.

To counteract this detrimental cycle, leading cancer centers are increasingly adopting a holistic approach to cancer management, integrating psychological support as a core component of care. At Cancer Treatment Centers of America in Zion, Illinois, Julie N.’s oncologist connected her with a social worker and a mind-body counselor. Her medical team also strongly encouraged her to seek weekly counseling sessions in her local community. The primary aim was to intervene proactively before depression spiraled out of control.

Identifying and Treating Cancer-Related Depression

Regardless of the specific triggers for depression and anxiety in cancer patients, early identification and diagnosis are paramount. Dr. David Spiegel, a professor of Medicine and Psychiatry at Stanford University School of Medicine, emphasizes this point. “Part of the problem is that depression is frequently underdiagnosed in people with cancer because there’s a common assumption, ‘Well, of course, you’re depressed. You have cancer,’” he notes.

“Cancer is undeniably a serious and life-altering diagnosis, but not everyone diagnosed with cancer will develop clinical depression.” The intensity of depression and anxiety can fluctuate throughout the cancer journey. Research by Leah Pyter, a psychiatry and neuroscience professor at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, and her colleagues, indicates that these emotional disturbances can persist and even worsen even after successful cancer treatment.

“In a subset of cancer survivors, inflammation does not fully resolve even after the tumor is removed,” Irwin explains. “There is considerable interest in understanding whether individuals who continue to experience persistent inflammation are also at a heightened risk for ongoing depression.”

Irwin highlights that initiating appropriate antidepressant medication early in cancer treatment can significantly reduce the incidence and severity of depression. However, careful consideration is needed when choosing antidepressants. Tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), two common classes of antidepressants, can sometimes worsen treatment side effects and potentially interfere with treatment effectiveness. For instance, SSRIs can inhibit the activation of tamoxifen, a breast cancer drug, potentially reducing its efficacy and increasing the risk of cancer recurrence.

“You have to be meticulous in selecting the right antidepressant,” Spiegel advises. Given that inflammation can suppress the body’s production of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and motivation, psychiatrists are increasingly turning to medications that boost dopamine levels and enhance motivation. “When individuals experience a lack of productivity, especially those who are naturally driven and want to be actively engaged in the world, stimulants can be beneficial,” he suggests. These may include SSRIs, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and other classes of drugs.

Studies also demonstrate that non-pharmacological approaches, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and regular exercise, can dramatically alleviate distress in cancer patients. Mind-body interventions, including hypnosis, meditation, yoga, and art therapy, also play a valuable role in reducing inflammation and anxiety, promoting better sleep, and improving overall well-being.

Cutting-edge approaches are now targeting the inflammatory pathways that underlie depression in cancer patients. “To mitigate the potential for depression, we could intervene in these inflammatory pathways following a cancer diagnosis, through dietary modifications, exercise regimens, or targeted medications,” Pyter suggests.

While depression and anxiety are not exclusive indicators of cancer, it’s crucial to recognize that cancer induces profound physiological changes that can significantly impact brain function and mental health. Increased awareness of this intricate link can encourage more proactive screening for depressive symptoms, potentially leading to earlier diagnoses of both depression and cancer.

“Whether or not depression serves as an early signal of cancer, depression is a significant health concern in its own right,” emphasizes Annette Stanton, a professor of psychology and psychiatry/biobehavioral sciences at UCLA. “Just because you are experiencing depression does not automatically mean you have cancer, and importantly, effective treatments for depression are readily available.”

In the realm of cancer care, the critical question of whether effectively treating anxiety and depression can actually improve cancer survival outcomes remains an active area of investigation in both clinical settings and research laboratories. The insights gleaned from these ongoing studies hold the potential to pave the way for more effective and comprehensive treatments for cancer and its associated symptoms, both physical and emotional.

Holly Alejos actively sought treatment for her depression. Nearly two years post-diagnosis, she has been taking the antidepressant Effexor (venlafaxine) since March 2019 and began therapy in August of the same year. “Between my therapist and my antidepressant, I have been able to process everything,” she shares. “It has profoundly improved my life. If I had been aware of the strong connection between depression and cancer earlier, I would have sought treatment for depression much sooner.”