INTRODUCTION

Celiac disease (CD) is an immune-mediated disorder triggered by gluten in genetically predisposed individuals, causing small intestinal inflammation. Globally, CD prevalence is estimated between 0.6% and 1%. Once considered rare, CD is now recognized as a significant health concern worldwide. Advances in diagnostic tools and understanding of its pathogenesis have propelled CD to global prominence. Consequently, international expert societies have developed guidelines to standardize CD diagnosis and management. This review aims to compare and critically analyze the most recent international guidelines for celiac disease, focusing on the Celiac Disease Diagnosis Criteria and highlighting key areas of convergence and divergence.

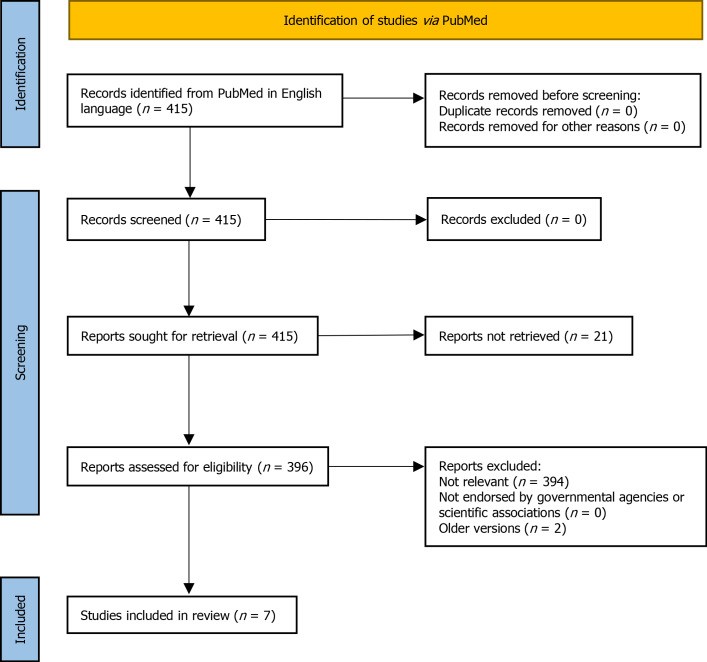

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A comprehensive search of PubMed was conducted to identify clinical guidelines on celiac disease published in English between January 2010 and January 2021. The search terms included “Celiac Disease,” “Coeliac Disease,” and “Guideline,” “Management.” Guidelines from governmental agencies and scientific societies focusing on CD diagnosis and management were included. Only the latest versions of guidelines were considered. Seven guidelines from recognized scientific societies were selected for analysis:

- European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) 2020

- European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) 2019

- World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO) 2017

- Central Research Institute of Gastroenterology, Russia, 2016

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2015

- British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG), 2014

- American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), 2013

The recommendations within each guideline were categorized into: patient selection for testing, diagnostic tests (serology, duodenal biopsy, genetic testing, no-biopsy diagnosis), potential/silent/seronegative CD, refractory/complicated CD, and follow-up procedures. This categorization covers the most critical aspects of celiac disease diagnosis criteria and management.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the guideline selection process.

RESULTS

Clinical Presentation and Risk Factors: Identifying Candidates for Celiac Disease Testing

Celiac disease presents diversely across all ages, ranging from classic intestinal symptoms to subtle extraintestinal manifestations. It’s crucial to consider CD in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals identified through screening. Symptoms can be broadly categorized as ‘classical’ (diarrhea, failure to thrive) and ‘non-classical’ (anemia, fatigue) reflecting the systemic nature of CD. Table 1 summarizes common clinical manifestations.

Table 1.

Most frequent clinical manifestations of celiac disease

| Intestinal | Extraintestinal |

|---|---|

| Classical | |

| Diarrhea | Iron deficiency anemia |

| Failure to thrive | Muscle wasting |

| Weight loss | Edema |

| Bloating | |

| Non classical | |

| Chronic abdominal pain | Short stature |

| Abdominal distension | Delayed puberty |

| Constipation | Amenorrhea |

| Vomiting | Irritability, unhappiness |

| Chronic fatigue | |

| Epilepsy | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | |

| Joint/muscle pain | |

| Elevated aminotransferases | |

| Aphthous stomatitis | |

| Recurrent miscarriages | |

| Reduced bone mineral density |

Certain guidelines emphasize specific extraintestinal presentations. ESsCD 2019 highlights oral-dental (enamel defects, recurrent aphthae) and neuropsychiatric manifestations. Russian guidelines note neurological and reproductive issues (delayed puberty, infertility, miscarriage).

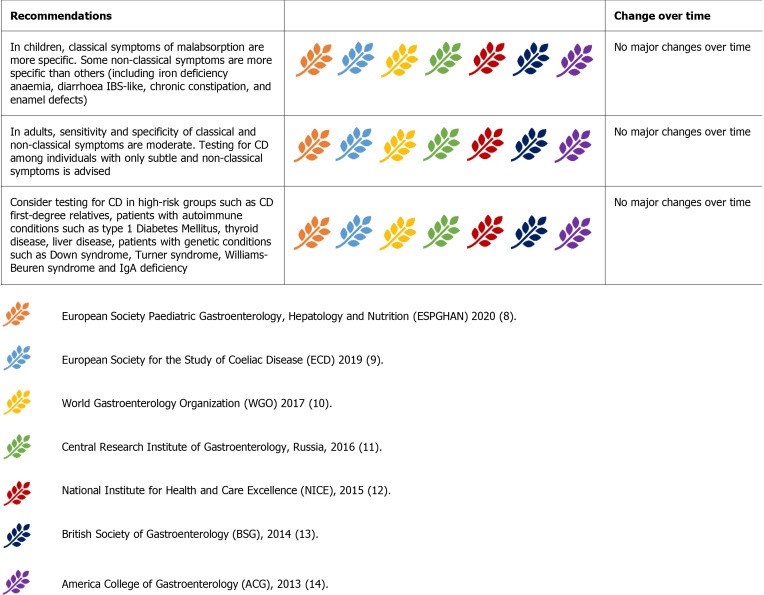

Figure 2.

Guideline recommendations for identifying individuals who should be tested for celiac disease.

All guidelines concur on testing individuals, both children and adults, presenting with classical and non-classical CD symptoms. Iron deficiency anemia and elevated liver enzymes are commonly recognized laboratory abnormalities prompting CD investigation.

High-risk groups consistently identified across guidelines include first-degree relatives of CD patients and individuals with associated conditions like type 1 diabetes, thyroid disorders, IgA deficiency, Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, and Williams-Beuren syndrome.

Diagnosis: Establishing Celiac Disease Diagnosis Criteria

No single “gold standard” test definitively diagnoses CD. Diagnosis relies on integrating clinical presentation, serology, and histology. Guidelines advocate a sequential approach: initial serological testing in high-risk individuals, followed by duodenal biopsy for positive serology or persistent malabsorption suspicion. Positive serology combined with villous atrophy on biopsy confirms CD. Discordant cases warrant HLA testing and evaluation in expert centers.

The “four-out-of-five rule,” while not formally endorsed by guidelines, provides a helpful framework. It suggests CD diagnosis when four of these criteria are met: typical symptoms, antibody positivity, HLA-DQ2/DQ8 presence, intestinal damage, and clinical response to a gluten-free diet (GFD). This rule aids in identifying CD subtypes (non-classic, seronegative, potential, non-responsive).

Serology: Initial Diagnostic Tests for Celiac Disease

Serological testing for celiac disease diagnosis criteria must be performed while the patient is consuming a gluten-containing diet. Serum IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody (anti-tTG-IgA) is the primary screening test, recognized for its sensitivity, though specificity can be lower at low titers. IgA anti-endomysial antibodies (EMA-IgA) offer near 100% specificity but are less sensitive and more operator-dependent, making them ideal as a second-line confirmatory test. Both tests are less reliable in IgA deficient individuals, where IgG-based tests like deamidated gliadin peptide (DGP) antibodies are preferred, especially in young children. Seronegative CD, lacking detectable serological markers, occurs in up to 2% of cases.

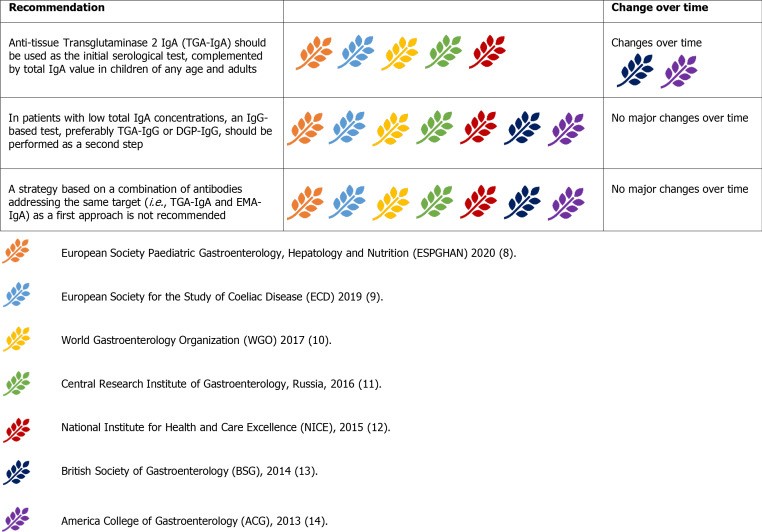

Current guidelines uniformly recommend anti-tTG-IgA as the initial serological test, along with total IgA level assessment to exclude IgA deficiency. This strategy applies to both children and adults. ACG 2013 and WGO 2017 guidelines suggest combining IgA and IgG antibodies (e.g., anti-tTG IgA and DGP-IgG) in children under two, but most guidelines advise against this due to reduced specificity and increased need for histological confirmation. DGP-IgG (with anti-tTG-IgG) remains the recommended test in IgA deficiency.

Figure 4.

Summary of guideline recommendations regarding serological testing for celiac disease diagnosis.

EMA-IgA serves as a confirmatory test, especially with low-titer anti-tTG-IgA, and is required for no-biopsy diagnosis in children with highly elevated anti-tTG IgA (> 10x upper limit of normal). Urine, stool, and saliva tests are discouraged due to poor performance and risk of misdiagnosis.

Biopsy: Histological Confirmation in Celiac Disease Diagnosis Criteria

Duodenal biopsy remains central to celiac disease diagnosis criteria, unanimously endorsed by all guidelines, although not considered CD-specific. Histological findings must be correlated with clinical and serological data.

Figure 5.

Guideline recommendations for duodenal biopsy in celiac disease diagnosis.

Biopsies are recommended for all suspected CD patients and high-risk symptomatic individuals regardless of serology results. Some suggest biopsies for any patient undergoing endoscopy due to CD’s prevalence and varied presentation. Multiple biopsy samples (four from the second duodenal portion and two from the bulb) are recommended due to the patchy nature of CD lesions. Proper biopsy orientation using Millipore filters is crucial to prevent artifacts.

Histological findings are classified using the Marsh-Oberhuber classification (Marsh 0-3c). Marsh 1 (increased intraepithelial lymphocytes – IELs) is non-specific and often due to other conditions. Marsh 2 includes crypt hyperplasia with increased IELs. Marsh 3 (villous atrophy with increased IELs) is typical for CD, further subcategorized (3a-c). While a simplified 3-grade system exists, guidelines currently recommend the Marsh-Oberhuber classification.

Alternative diagnostic tools like video-capsule endoscopy (VCE) are not routinely recommended over biopsy. VCE might be useful in adults with discordant serology/biopsy or contraindications to endoscopy, or to detect complications. Anti-actin IgA antibodies may predict severe villous atrophy but are not yet part of routine diagnosis. Fecal and salivary microbiome analysis is not currently reliable for CD diagnosis. Intestinal fatty-acid binding protein (I-FABP) shows promise as a blood marker for mucosal damage and dietary adherence.

Repeat biopsies, including jejunal biopsies, may be considered in adults with serology-histology discordance. In children, re-cutting biopsies or expert pathologist review is preferred over repeat endoscopy.

Gluten challenge is recommended for adults with uncertain CD diagnosis already on a GFD. It’s discouraged in young children and during puberty, reserved for unusual cases. Protocols vary, but 10g gluten/day for 6-8 weeks or 3g gluten/day for at least 2 weeks are common. Serology testing after 2 weeks of gluten challenge can optimize results. Symptoms alone during gluten challenge are insufficient for diagnosis without other evidence. In resource-limited settings, symptom-based diagnosis with GFD response and gluten re-introduction relapse may be considered when serology is unavailable.

Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) Testing: Genetic Predisposition in Celiac Disease Diagnosis Criteria

HLA-DQ2/DQ8 presence is a genetic prerequisite for CD, but its prevalence in the general population (30-40%) limits specificity. However, HLA-DQ2/DQ8 absence virtually excludes CD.

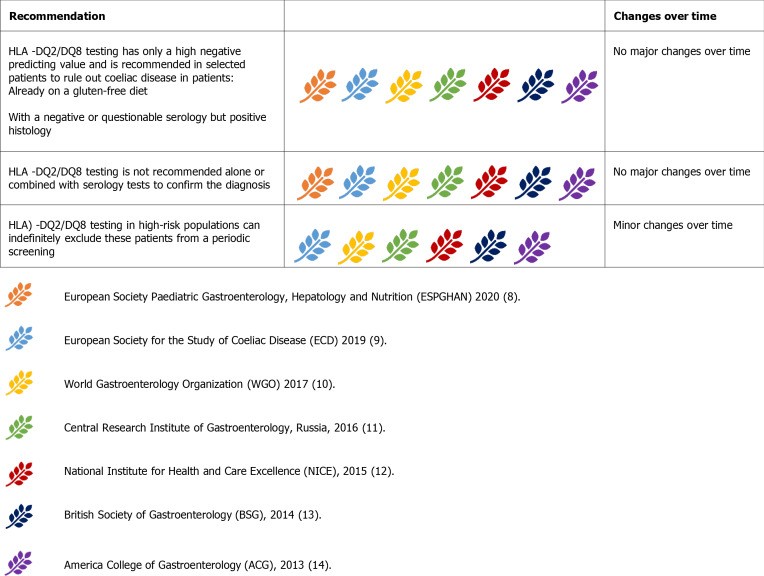

Figure 6.

Guideline recommendations on the role of HLA testing in celiac disease diagnosis.

Guidelines uniformly advise against HLA testing as a first-line diagnostic tool. Its role is in: uncertain CD diagnosis in patients on GFD, flat mucosa with negative serology, and inconclusive serology/histology in patients on GFD. HLA testing can guide the decision for gluten challenge. It is unhelpful in seropositive patients before gluten challenge as most will be HLA-DQ2/DQ8 positive. In histology-positive, seronegative cases, HLA testing can exclude CD. Positive HLA results do not confirm CD and require expert evaluation.

HLA testing in high-risk populations is debated. While common in first-degree relatives and those with associated conditions, routine HLA screening is not universally recommended due to resource implications. Some suggest screening high-risk individuals only if symptomatic or with laboratory abnormalities. Two-step genetic screening starting with HLA-DQ β chains has been proposed. The approach to HLA testing in high-risk groups remains debated, considering local resources and cost-benefit.

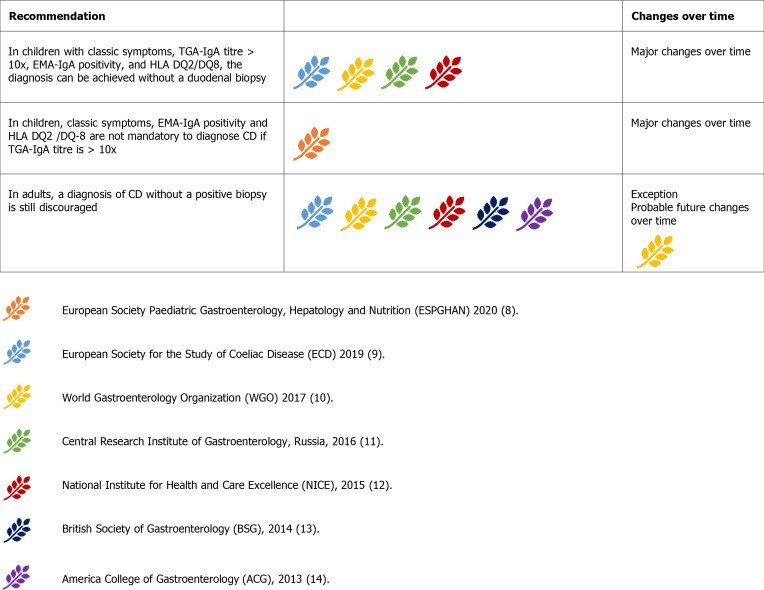

No-Biopsy Diagnosis: Evolving Celiac Disease Diagnosis Criteria in Children

While most guidelines mandate biopsy for adult CD diagnosis, a no-biopsy approach in children is increasingly accepted under strict conditions. WGO guidelines exceptionally allow diagnosis based on serology and GFD response in resource-limited settings.

Figure 7.

Guideline recommendations regarding the feasibility of no-biopsy diagnosis in celiac disease.

ESPGHAN 2012 first endorsed no-biopsy diagnosis in children with classic symptoms, anti-tTG-IgA > 10x upper limit of normal (ULN), EMA-IgA positivity, and permissive HLA. Many guidelines adopted this, except ACG 2013 and BSG 2014.

ESPGHAN 2020 update removed classic symptoms, EMA-IgA, and HLA as mandatory criteria, though EMA-IgA positivity is still supportive. Increasing confidence in no-biopsy diagnosis in children is evident, with some studies suggesting anti-tTG-IgA > 10x as a potential cut-off to minimize biopsies.

No-biopsy diagnosis remains discouraged in adults. While serology is reliable in adults (anti-tTG-IgA>10x predicts villous atrophy), concerns about complications at presentation, differential diagnoses, and the value of baseline histology in predicting future complications justify biopsy in adults. Complicated CD and differential diagnoses are less common in children, supporting age-specific diagnostic algorithms.

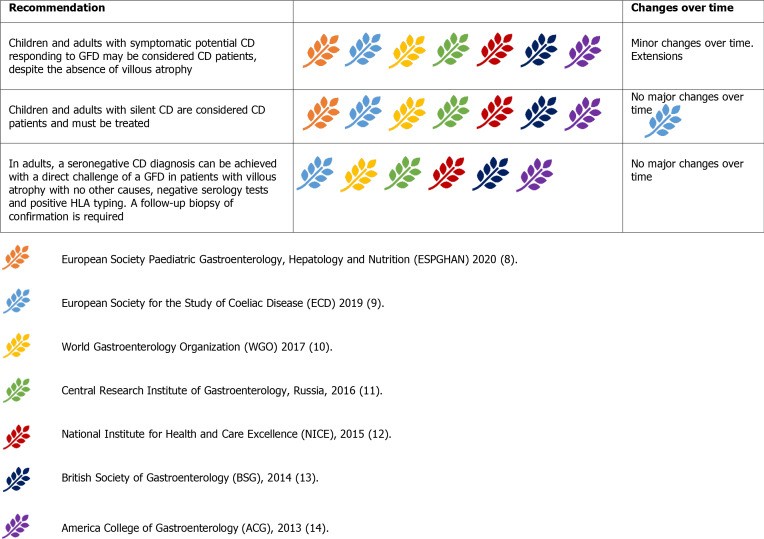

Potential, Silent, and Seronegative CD: Variations in Celiac Disease Presentation

Potential CD involves positive serology without villous atrophy. Marsh 1 lesions (increased IELs) increase villous atrophy risk. Symptomatic potential CD may benefit from GFD. In adults with both positive anti-tTG-IgA and EMA-IgA, GFD may be initiated regardless of symptoms, with serological response after 12 months confirming CD. EMA-IgA negativity and HLA-typing can guide follow-up and exclude CD. Retesting potential CD patients after gluten consumption for 3-6 months is recommended before considering repeat endoscopy.

Figure 8.

Guideline recommendations for managing potential, silent, and seronegative celiac disease.

Silent CD presents with positive serology and histology but lacks typical symptoms. GFD initiation is recommended as it is considered an active form of CD.

Seronegative CD involves enteropathy with negative serology, responding clinically and histologically to GFD, after excluding other causes. HLA-typing can exclude CD in seronegative enteropathies. Gluten challenge is advised only in HLA-positive seronegative enteropathy patients, with histological response to GFD confirming diagnosis. Management of seronegative CD has remained consistent over time.

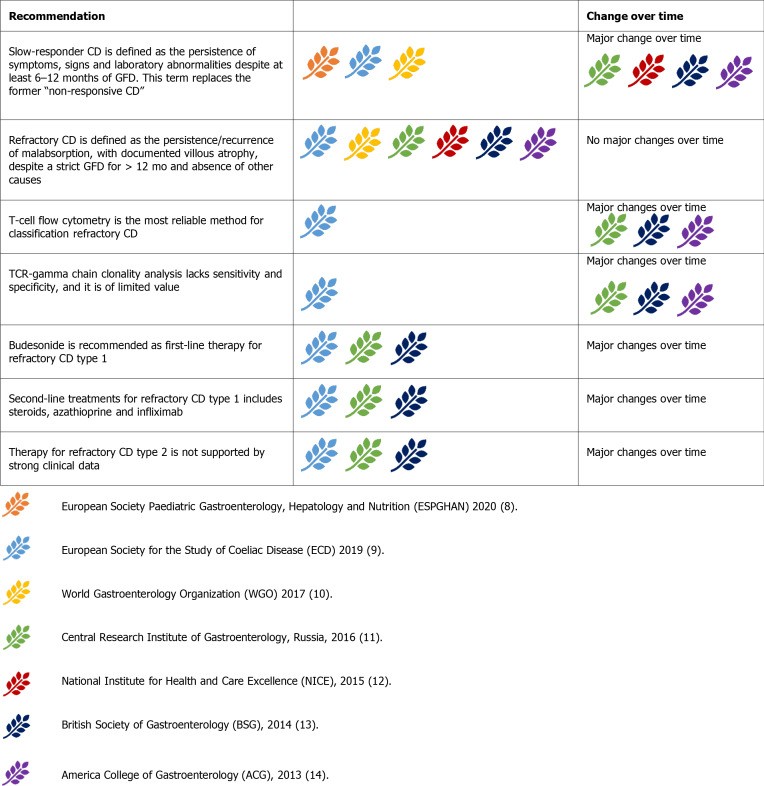

Refractory and Complicated CD: Managing Complex Presentations

Refractory CD (RCD) is persistent or recurrent CD despite strict GFD for over 12 months, excluding other causes. Complications include enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) and duodenal adenocarcinoma.

Figure 9.

Guideline recommendations for managing refractory and complicated celiac disease.

Initial RCD evaluation involves re-evaluating the original CD diagnosis and excluding inadvertent gluten ingestion (expert dietitian consultation is crucial) and other conditions (lactose intolerance, SIBO, microscopic colitis, pancreatic insufficiency, IBD).

RCD is classified as type 1 (RCD-1) and type 2 (RCD-2) using T-cell flow cytometry (aberrant T cells CD3-CD8+CD3+cytoplasmic). RCD-1 has <20% aberrant T cells, RCD-2 has >20% and is considered pre-lymphoma. TCR clonality analysis is no longer recommended for RCD classification.

RCD-1 treatment is budesonide (open-capsule) as first-line, with systemic steroids and azathioprine as second-line. Infliximab may be considered. RCD-1 has a high 5-year survival rate.

RCD-2 is rarer, with higher mortality. Systemic steroids or budesonide are first-line for milder cases. Severe cases require cytoreductive therapies (cladribine, fludarabine, stem cell transplant). Other therapies (azathioprine, methotrexate, anti-TNF) have weaker evidence. Transformation to EATL is a risk in RCD-2. VCE, PET, and MR enterography are useful for staging. Severe RCD-2 and EATL may require surgery, chemotherapy, or bone marrow transplantation.

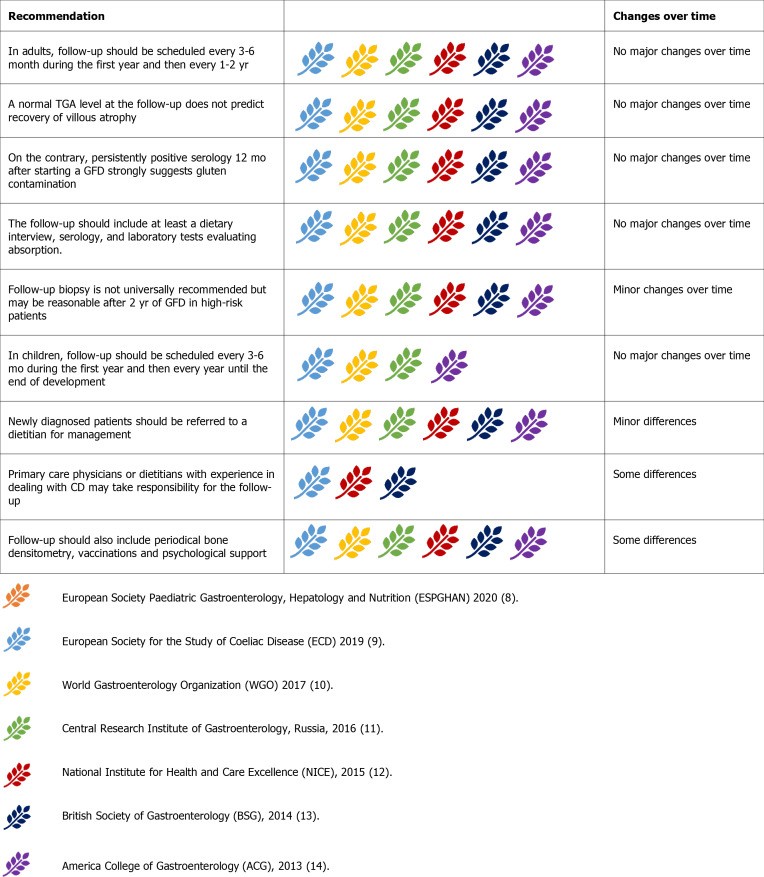

Follow-up: Long-Term Management of Celiac Disease

Long-term monitoring is essential for CD patients to assess GFD compliance, treatment response, and complications. Follow-up is recommended every 3-6 months initially, then annually or bi-annually. In children, follow-up continues until final height is reached, focusing on growth and development.

Figure 10.

Guideline recommendations for follow-up management of celiac disease.

Follow-up responsibility is debated; NICE guidelines suggest dietitians, while others show no preference. All agree on dietitian referral for new diagnoses. Follow-up includes dietary interviews, serology (anti-tTG-IgA), and laboratory tests (micronutrient levels, thyroid function, liver enzymes). Persistently positive serology after 12 months suggests gluten ingestion.

Follow-up biopsies are not routine in asymptomatic, uncomplicated patients on GFD. Repeat biopsies after 2 years of GFD are considered reasonable by some guidelines to assess mucosal healing, especially in those diagnosed after 40 or with classical presentation. Others recommend biopsies only for persistent symptoms or serological abnormalities after 12 months of GFD.

Bone densitometry is recommended at diagnosis by some guidelines, repeated at 3 or 5 years. Others recommend it only for high-risk osteoporosis patients or those over 55. Pneumococcal vaccine is generally recommended; WGO also suggests Haemophilus influenzae type B and Meningococcus vaccines. Psychological support and CD support groups are advised to address mood disorders.

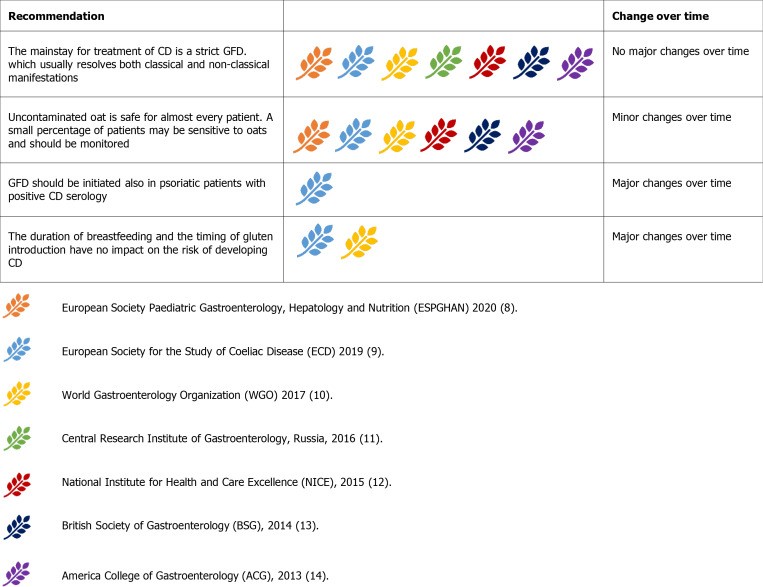

Gluten-Free Diet: Cornerstone of Celiac Disease Management

GFD is the primary treatment for CD. Gluten, found in wheat, rye, and barley, must be avoided. Uncontaminated oats are safe for most CD patients, but monitoring is advised due to potential sensitivity in some individuals. Some guidelines initially exclude oats, while Russian guidelines advise against them due to contamination risk.

Figure 11.

Guideline recommendations for implementing a gluten-free diet in celiac disease.

“Gluten-free” labeled foods must contain ≤ 20 ppm gluten according to WHO standards. Patients should avoid gluten cross-contamination using separate utensils and surfaces, although thorough cleaning with soap and water is generally sufficient for shared items.

Breastfeeding duration and timing of gluten introduction in infants do not impact CD risk, removing prior recommendations against early or late gluten introduction.

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), a cutaneous manifestation of CD, requires GFD treatment. ESsCD guidelines suggest GFD may benefit psoriasis patients with documented CD serology, even without mucosal damage.

DISCUSSION

This comparative analysis reveals both consensus and divergence in international celiac disease diagnosis criteria and management guidelines. Differences in diagnostic approaches, particularly regarding no-biopsy diagnosis, and follow-up protocols reflect varying clinical contexts and resource availability.

The no-biopsy diagnosis in children is a significant advancement, particularly relevant in resource-limited settings. While most guidelines remain cautious, WGO guidelines acknowledge its necessity where endoscopy is limited. CD prevalence in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa may be underestimated due to limited awareness and resources. Specific guidelines are needed for these regions. The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the need for less invasive diagnostic approaches. While no-biopsy diagnosis is largely pediatric, increasing evidence may support its extension to adults in future guidelines.

Follow-up recommendations also show variability, reflecting past underemphasis. With improved CD diagnosis, effective follow-up is crucial, especially in developed countries where metabolic complications of GFD are prevalent (weight gain, metabolic syndrome, NAFLD). Early detection of associated autoimmune conditions and complicated CD (neoplastic and non-neoplastic) also warrants robust follow-up strategies.

CONCLUSION

International guidelines for celiac disease diagnosis criteria show considerable agreement, particularly on core diagnostic and management principles. Key modifications in recent years include the acceptance of no-biopsy diagnosis in children. Future guideline revisions will likely focus on expanding non-invasive diagnostic approaches, potentially to adult populations, and refining follow-up protocols to address long-term management and emerging complications.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research Background

Celiac disease (CD) has become a global health issue, prompting international societies to develop diagnostic and management guidelines.

Research Motivation

While CD guidelines agree on core principles, variations exist, necessitating a comparative analysis.

Research Objectives

To compare international CD guidelines, identify similarities and differences, and discuss evolving diagnostic and management strategies.

Research Methods

PubMed search for recent CD guidelines, categorizing recommendations across seven international guidelines.

Research Results

Seven guidelines were analyzed (ESPGHAN 2020, ESsCD 2019, WGO 2017, Russia 2016, NICE 2015, BSG 2014, ACG 2013), revealing consensus and divergence on no-biopsy diagnosis, refractory CD, and follow-up.

Research Conclusions

High concordance exists among CD guidelines, with no-biopsy diagnosis in children being a major recent advancement.

Research Perspectives

Future guidelines will likely evolve towards broader no-biopsy diagnosis (especially in developing countries) and refined follow-up modalities.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: March 2, 2021

First decision: July 14, 2021

Article in press: December 25, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Poddighe D, Sabelnikova EA, Sahin Y, Vasudevan A

S-Editor: Wang LL

L-Editor: A

P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Alberto Raiteri, Division of Internal Medicine, Hepatobiliary and Immunoallergic Diseases, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna 40138, Italy.

Alessandro Granito, Division of Internal Medicine, Hepatobiliary and Immunoallergic Diseases, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna 40138, Italy.

Alice Giamperoli, Division of Internal Medicine, Hepatobiliary and Immunoallergic Diseases, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna 40138, Italy.

Teresa Catenaro, Division of Internal Medicine, Hepatobiliary and Immunoallergic Diseases, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna 40138, Italy.

Giulia Negrini, Division of Internal Medicine, Hepatobiliary and Immunoallergic Diseases, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna 40138, Italy.

Francesco Tovoli, Division of Internal Medicine, Hepatobiliary and Immunoallergic Diseases, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Bologna 40138, Italy. [email protected].